Contemporary Emirati Literature: Its Historical Development and Forms*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The European Union and the United Arab Emirates As Civilian and Soft

Krzymowski, A. (2020). The European Union and the United Arab Emirates as Journal civilian and soft powers engaged in Sustainable Development Goals. Journal of of International International Studies, 13(3), 41-58. doi:10.14254/2071-8330.2020/13-3/3 Studies © Foundation The European Union and the United of International Studies, 2020 Arab Emirates as civilian and soft powers © CSR, 2020 Papers Scientific engaged in Sustainable Development Goals Adam Krzymowski Department of International Studies, Zayed University, United Arab Emirates [email protected] ORCID 0000-0001-9296-6387 Abstract. The article analyses the European Union (EU) – as European international Received: December, 2019 organisation and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – the only federal state in the 1st Revision: Arab World as civilian and soft powers, strongly active to reach the UN 2030 June, 2020 Agenda. The ambitious projects, as well as actions, strategies, and visions of this Accepted: August, 2020 international entity for reaching Sustainable Development Goals, should be analysed due to its impact on the international environment and emerging new DOI: international relations architecture. The author carried out research using 10.14254/2071- primarily descriptive and analytical methods. To this end, rich source material, 8330.2020/13-3/3 such as documents, strategies, and statements has been tested. In findings, the article presents the EU and the UAE as civilian and soft powers, its projects, and their implementation, including the green economy program, the energy strategies, and initiatives related to climate changes, humanitarian aid as well as in favour for peace, security, and tolerance. This research in conclusion demonstrates the role and significance of Sustainable Development Goals for the European Union as well as the United Arab Emirates strengthening power in the international arena. -

Catalog INTERNATIONAL

اﻟﻤﺆﺗﻤﺮ اﻟﻌﺎﻟﻤﻲ اﻟﻌﺸﺮون ﻟﺪﻋﻢ اﻻﺑﺘﻜﺎر ﻓﻲ ﻣﺠﺎل اﻟﻔﻨﻮن واﻟﺘﻜﻨﻮﻟﻮﺟﻴﺎ The 20th International Symposium on Electronic Art Ras al-Khaimah 25.7833° North 55.9500° East Umm al-Quwain 25.9864° North 55.9400° East Ajman 25.4167° North 55.5000° East Sharjah 25.4333 ° North 55.3833 ° East Fujairah 25.2667° North 56.3333° East Dubai 24.9500° North 55.3333° East Abu Dhabi 24.4667° North 54.3667° East SE ISEA2014 Catalog INTERNATIONAL Under the Patronage of H.E. Sheikha Lubna Bint Khalid Al Qasimi Minister of International Cooperation and Development, President of Zayed University 30 October — 8 November, 2014 SE INTERNATIONAL ISEA2014, where Art, Science, and Technology Come Together vi Richard Wheeler - Dubai On land and in the sea, our forefathers lived and survived in this environment. They were able to do so only because they recognized the need to conserve it, to take from it only what they needed to live, and to preserve it for succeeding generations. Late Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan viii ZAYED UNIVERSITY Ed unt optur, tet pla dessi dis molore optatiist vendae pro eaqui que doluptae. Num am dis magnimus deliti od estem quam qui si di re aut qui offic tem facca- tiur alicatia veliqui conet labo. Andae expeliam ima doluptatem. Estis sandaepti dolor a quodite mporempe doluptatus. Ustiis et ium haritatur ad quaectaes autemoluptas reiundae endae explaboriae at. Simenis elliquide repe nestotae sincipitat etur sum niminctur molupta tisimpor mossusa piendem ulparch illupicat fugiaep edipsam, conecum eos dio corese- qui sitat et, autatum enimolu ptatur aut autenecus eaqui aut volupiet quas quid qui sandaeptatem sum il in cum sitam re dolupti onsent raeceperion re dolorum inis si consequ assequi quiatur sa nos natat etusam fuga. -

Union Square Bus Station - Fujairah E700 ������� � ������ ����� ����� ��

Union Square Bus Station - Fujairah E700 Friday Union Square Bus Station 05.30 06.30 08.00 09.30 11.00 12.30 14.00 15.30 17.00 18.30 20.00 21.30 DNATA 05.34 06.34 08.04 09.35 11.05 12.35 14.05 15.35 17.07 18.37 20.06 21.36 Airport Terminal 1, Arrival 05.39 06.39 08.09 09.42 11.12 12.42 14.11 15.42 17.15 18.45 20.13 21.43 Sharjah Cement Factory 06.17 07.17 08.47 10.30 12.00 13.19 14.41 16.25 17.55 19.27 20.55 22.24 Dhaid, Post Office 06.39 07.39 09.09 10.52 12.23 13.42 15.05 16.51 18.24 19.51 21.20 22.47 Dhaid, Central Region 06.40 07.40 09.10 10.53 12.24 13.43 15.06 16.52 18.26 19.52 21.21 22.48 Department Thoban ENOC Petrol Station 06.52 07.52 09.22 11.05 12.35 13.55 15.19 17.05 18.41 20.05 21.34 23.00 Masafi, Friday Market 07.01 08.01 09.31 11.14 12.44 14.04 15.29 17.15 18.53 20.16 21.44 23.09 Masafi, Police Station 07.06 08.06 09.35 11.19 12.49 14.09 15.34 17.21 19.00 20.21 21.49 23.14 Fujairah, Ajman University 07.30 08.30 09.59 11.43 13.15 14.34 16.00 17.48 19.31 20.52 22.17 23.41 Fujairah Bus Station, External 07.32 08.32 10.01 11.45 13.17 14.36 16.02 17.50 19.33 20.54 22.19 23.43 Fujairah, Etisalat 07.34 08.34 10.03 11.47 13.19 14.38 16.04 17.53 19.36 20.57 22.22 23.45 Fujairah, Ministry Of Labour 07.35 08.35 10.04 11.48 13.20 14.39 16.05 17.54 19.37 20.58 22.23 23.46 Fujairah, Choithrams 07.35 08.35 10.05 11.48 13.21 14.40 16.06 17.55 19.37 20.58 22.24 23.47 Supermarket Fujairah 07.36 08.36 10.05 11.49 13.21 14.40 16.06 17.55 19.38 20.59 22.24 23.48 Sunday to Wednesday -

Choose the Right Answer Q1: 1

Social Studies Revision Sheet –Third term AY 2018/2019 Grade 2 Q1: Choose the right answer for the following sentences: 1-Areesh houses reflected the customs and ……………..of the Emirates. A- Traditions B- Helping C- Kindness 2-Pillars called "……………………" in the Emirati dialect. A- Yado`o B- Picking C- Kicking 3- ………………….are the parts that make the bases of the Areesh. A- Leaves B- Palm fronds C- Da`an 4- ……………………….is used for the roof of the Areesh. A- Da`an B- Palm fronds C- Bricks 5- Traditional bread for the Emirati is called ……………………. A- Chbab B- Toast C- Chapatti Q2: Choose the right answer from the table: Abaya - Isama Bisht - Egal - Burqa A- 1-Men tie the Ghutra around their heads without egal. This is called Isama ,and it`s an old habit. 2- ………Bisht…….. is a cloak worn by men. 3-……Burqa……. is made of golden paper-like cloth sewn to cover the woman`s face expect for a slit for the eyes. 4- …Abaya… is made of black fabric, Emirati women used to wear it. 5-…Egal….. is a wool braid placed on the Ghutra as a headdress. Q3: Look at the map and finish the sentences: A-………Abu Dhabi……………is the capital of the UAE. B-Burj Khalifa is in ……… Dubai………..Emirate. C-There are ……………seven………….emirates in the UAE. D-………Ajman…………………is the smallest Emirate in the UAE. E-This is the map of ………United Arab Emirates……. Q4: Put ( √ ) for the correct sentences and ( X ) for the wrong sentences: A-Al Areesh houses were made from bricks ( x ) B-Traditional Emirati bread Chbab is similar to toast ( x ) C-The Emiratis still keep their traditional food (√ ) D-When I see Chbab , I remember pancake (√ ) E-The cloak worn by Emirati men is called Candurah ( x ) Q5: Help Maryam to match clothes items to the correct place: . -

The Palatalisation of /ʤ/ Into /J/ in Emirati Arabic (EA): a Rule-Governed Or Random Alternation?

International Journal of Linguistics ISSN 1948-5425 2017, Vol. 9, No. 5 The Palatalisation of /ʤ/ into /j/ in Emirati Arabic (EA): A Rule-Governed or Random Alternation? Hodan Mohamoud Hassan Department of English Language Teaching, College of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Al Ain University of Science and Technology P.O. Box: 64141, Al Ain, UAE Tel: 971-3702-4888 Fax: 971-3702-4777 Received: Sep. 15, 2017 Accepted: September 28, 2017 Published: October 8, 2017 doi:10.5296/ijl.v9i5.11964 URL: https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v9i5.11964 Abstract This study aims to investigate a phonological phenomenon that occurs in Emirati Arabic (EA), whereby the voiced palato-alveolar affricate /ʤ/ changes into the voiced palatal approximate (glide) /j/. In particular, this study attempts to determine whether this phonological alternation is triggered by a certain phonological environment, or whether it occurs randomly without any rule. It also endeavours to examine the hypothesis that this phonological phenomenon was borrowed from other Arabic dialects spoken in the Gulf through language contact. Keywords: Phonological alternation, palatalisation, Emirati Arabic, language contact 173 www.macrothink.org/ijl International Journal of Linguistics ISSN 1948-5425 2017, Vol. 9, No. 5 1. Introduction The linguistic situation of Arabic can be described as complex due to the existence of two types of varieties, namely, Modern Standard Arabic (henceforth MSA) and Colloquial Arabic (henceforth CA) (Khalifa et al. 2016). MSA is the official language variety in Arab countries; it is the language used in writing, official speeches, sermons, correspondence and the media, whereas CA is the one used in everyday life. -

Rta Bus Routes List 2019

Dubai Bus ﻻﺋﺤﺔ ﺧﻄﻮط اﻟﺤﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻌﺎﻣﺔ ﻳﻨﺎﻳﺮ ٢٠١٩ Bus Route Service List January 2019 رﻗﻢ اﻟﺨﻂ ﻳﻨﻄﻠﻖ ﻣﻦ ﻳﺼﻞ ﻟﻐﺎﻳﺔ رﻗﻢ اﻟﺨﻂ ﻳﻨﻄﻠﻖ ﻣﻦ ﻳﺼﻞ ﻟﻐﺎﻳﺔ Route ID Start from End - to Route ID Start from End - to اﻟﺨﻄﻮط اﻟﺴﻳﻌﺔ اﻟﺨﻄﻮط اﻟﻌﺎﻣﺔ Express Bus Routes Local Bus Routes 13B ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻘﺼﻴﺺ 7 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﺴﻄﻮة اﻟﻘﻮز ﺟﻲ ﻣﺎرت 13B Gold Souq Bus Stn Al Qusais Bus Stn 7 Al Satwa Bus Stn Al Quoz, J Mart 91A ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺟﺒﻞ ﻋ 8 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﻣﺘﺮو اﺑﻦ ﺑﻄﻮﻃﺔ 91A Gold Souq Bus Stn Jebel Ali Bus Stn 8 Gold Souq Bus Stn Ibn Battuta MS X02 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ اﻟﻐﺒﻴﺒﺔ اﻟﺴﻄﻮة ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻐﺒﻴﺒﺔ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﻣﺘﺮو ﻣﻌﺒﺮ اﻟﺨﻠﻴﺞ اﻟﺘﺠﺎري X02 Al Ghubaiba Bus Stn Al Satwa 9 Al Ghubaiba Bus Stn Business Bay MS 9 X13 ﻗﻳﺔ اﻟﻠﻮﻟﻮ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﺴﻄﻮة 10 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻘﻮز X13 LuLu Village Al Satwa Bus Stn 10 Gold Souq Bus Stn Al Quoz Bus Stn X22 ﻣﻨﻄﻘﺔ اﻟﻘﺼﻴﺺ اﻟﺼﻨﺎﻋﻴﺔ 2 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﻣﺘﺮو ﻣﻌﺒﺮ اﻟﺨﻠﻴﺞ اﻟﺘﺠﺎري 11A ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ اﻟﻌﻮﻳﺮ X22 Al Qusais Ind'l Area 2 Business Bay MS 11A Gold Souq Bus Stn Al Awir X23 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ اﻟﻤﺪﻳﻨﺔ اﻟﻌﺎﻟﻤﻴﺔ 11B ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﻣﺘﺮو اﻟﺮاﺷﺪﻳﺔ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ اﻟﻌﻮﻳﺮ 11B Rashidiya MS Al Awir Terminus X23 Gold Souq Bus Stn International City ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻐﺒﻴﺒﺔ X25 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻜﺮاﻣﺔ د ﻟﻠﺘﻌﻬﻴﺪ, ﺑﻨﻚ أﺳﻜﺘﻠﻨﺪا اﻟﻤﻠﻜﻲ 2 12 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻘﻮز Al Ghubaiba Bus Stn Al Quoz Bus Stn 12 X25 Al Karama Bus Stn Dubai Outsourcing 13 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ اﻟﻘﺼﻴﺺ ﻣﺴﺎﻛﻦ اﻟﻌﻤﺎل Gold Souq Bus Stn Al Qusais DM Housing X28 ﻗﻳﺔ اﻟﻠﻮﻟﻮ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﻣﺘﺮو ﻣﺪﻳﻨﺔ د ﻟﻼﻧﺘﺮﻧﺖ LuLu Village Dubai Internet City MS 13 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻘﺼﻴﺺ X28 13A -

United Arab Emirates's Constitution of 1971 with Amendments Through 2004

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:52 constituteproject.org United Arab Emirates's Constitution of 1971 with Amendments through 2004 © Oxford University Press, Inc. Prepared for distribution on constituteproject.org with content generously provided by Oxford University Press. This document has been recompiled and reformatted using texts collected in Oxford’s Constitutions of the World. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:52 Table of contents Preamble . 3 CHAPTER ONE: THE UNION, ITS FUNDAMENTAL CONSTITUENTS AND AIMS . 3 CHAPTER TWO: THE FUNDAMENTAL SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC BASES OF THE UNION . 5 CHAPTER THREE: FREEDOMS, RIGHTS AND PUBLIC DUTIES . 7 CHAPTER FOUR: THE UNION AUTHORITIES . 9 SECTION 1: THE SUPREME COUNCIL OF THE UNION . 10 SECTION 2: THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNION AND HIS DEPUTY . 11 SECTION 3: THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS OF THE UNION . 13 SECTION 4: THE UNION NATIONAL COUNCIL . 16 Sub-Section 1: General Provisions . 16 Sub-Section 2: Organisation of work in the Council . 18 Sub-Section 3: Powers of the Council . 20 SECTION 5: THE JUDICIARY IN THE UNION AND THE EMIRATES . 21 CHAPTER FIVE: UNION LEGISLATION AND DECREES AND THE AUTHORITIES HAVING JURISDICTION THEREIN . 25 SECTION 1: UNION LAWS . 25 SECTION 2: DECREE LAWS . 26 SECTION 3: ORDINARY DECREES . 26 CHAPTER SIX: THE EMIRATES . 26 CHAPTER SEVEN: THE DISTRIBUTION OF LEGISLATIVE,EXECUTIVE AND INTERNATIONAL JURISDICTION BETWEEN THE UNION AND THE EMIRATES . 27 CHAPTER EIGHT: THE FINANCIAL AFFAIRS OF THE UNION . 29 CHAPTER NINE: THE ARMED FORCES AND THE SECURITY FORCES . -

The Interference of Arabic Prepositions in Emirati English

Article The Interference of Arabic Prepositions in Emirati English Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila 1,2 1 ESERP Business and Law School, 08010 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] or [email protected] 2 Department of Applied Linguistics, Faculty of Philology, University Complutense of Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain Abstract: The bond between England and the UAE date back to over 220 years ago. This article explored the interference of Arabic prepositions in the English used in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and their occurrences in light of gender and level of education, two important social variables related to linguistic behavior. To do so, participants translated 20 sentences in Arabic into English as well as filled in 30 gaps in sentences in English with the missing prepositions. We also experimented how musical intelligence improved the Emiratis’ performance regarding prepositions. An experiment was carried out to verify if participants from the experimental group, who received training on prepositions through music, obtained better results compared to the control group, who received training through a more traditional way (by listening to the instructor and repeating). Keywords: multiple intelligences; musical intelligence; grammar; prepositions; contrastive; compar- ative; linguistics; L2 acquisition; training; Emirati English; Arabic dialects; autism; savant syndrome 1. Introduction This study aims to analyze the utilization of the Theory of Multiple Intelligences (MI) Citation: Ribeiro Daquila, J.P. The as an instrument to enhance learning. MI was presented by the American developmental Interference of Arabic Prepositions in psychologist and research professor Howard Gardner in 1983 in his notable book Frames of Emirati English. Sci 2021, 3, 19. -

Dubai Metro: Building the World's Longest Driverless Metro

Civil Engineering Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers Volume 165 Issue CE3 Civil Engineering 165 August 2012 Issue CE3 Pages 114–122 http://dx.doi.org/10.1680/cien.11.00071 Dubai Metro: building the world’s Paper 1100071 longest driverless metro Received 22/12/2011 Accepted 05/04/2012 Botelle, McSheffrey, Zouzoulas and Burchell Keywords: railway systems/tunnels & tunnelling/viaducts proceedings ICE Publishing: All rights reserved Dubai Metro: building the world’s longest driverless metro 1 Matthew Botelle MSc, RPP MAPM, CMILT 3 Petros Zouzoulas BA, LEED AP, AIA Parsons programme director for Dubai Metro, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Parsons senior architect for Dubai Metro, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 2 Patrick McSheffrey BEng, CEng, FICE 4 Anthony Burchell BSc, CEng, FICE Formerly Parsons construction manager for Dubai Metro, now Parsons senior Formerly Systra project director for Dubai Metro, now Parsons construction manager for Etihad Rail, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Brinckerhoff project director for Doha Metro, Doha, Qatar 1 2 3 4 The 23 km Green line of the Dubai Metro opened in September 2011, exactly 2 years after the 52 km Red line, making it the world’s longest driverless metro. In a city dominated by the car but projecting heavy population growth, the metro has been designed to provide unparalleled levels of customer comfort and finishing, together with the frequency, punctuality and coverage to meet the emirate’s future strategic needs and ambitions. This paper provides an overview of the £4·8 billion project, with particular emphasis on the heavy civil engineering solutions delivered within a highly stylised and exacting architectural context, from an outline plan in 2002 to a fully operational reality in 2011. -

Union View U Nion Confederation I T U C Nternational Trade May 2011

#07#09 #21#12 nion Confederation U nternational Trade nternational Trade I C U T UNION VIEW I May 2011 g Matilde Gattoni Hidden faces of the Gulf miracle Behind the gleaming cities of Doha (Qatar) and Dubai (UAE), stories of migrant workers with few rights and inhuman living conditions. #21 Migrant worker misery lies behind gleaming towers of Gulf cities VIEW UNION • 2 MAY 2011 MAY g Matilde Gattoni t’s hard not to be impressed by a first sight of the gleaming tion often rudimentary and air-conditioning when it exists is Inew cities springing out of the desert coast of the Persian sometimes ineffectual when summer temperatures soar over Gulf. 40˚C. Many work at dangerous jobs with little or no health insurance. Dubai oozes glamour and bristles with superlatives: the world’s tallest building, most luxurious hotels and biggest The migrant workers are nothing if not resistant. Many say shopping malls and vast artificial islands. they are willing to put up with the heat and harsh conditions In Doha, an ongoing building boom is poised to move up for the chance to support their families with wages way several gears as work kicks off on a massive infrastructure beyond what they can earn at home. All too often however, programme in preparation for the 2022 World Cup. salaries are paid months overdue. The downtown skyline of Qatar’s capital already glistens like Conned by unscrupulous recruitment agents, workers arrive a Middle Eastern Manhattan across the bay from the iconic in the Gulf to discover they are paid considerably less than architecture of its new Museum of Islamic Art. -

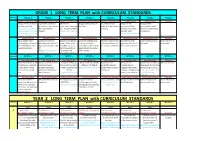

YEAR 2 LONG TERM PLAN with CURRICULUM STANDARDS YEAR 2 WEEK 1 WEEK 2 WEEK 3 WEEK 4 WEEK 5 WEEK 6 WEEK 7 WEEK 8

GRADE 1 LONG TERM PLAN with CURRICULUM STANDARDS GRADE 1 WEEK 1 WEEK 2 WEEK 3 WEEK 4 WEEK 5 WEEK 6 WEEK 7 WEEK 8 Emirates Throughout HistoryEmirates Throughout HistoryEmirates Throughout HistoryEmirates Throughout HistoryEmirates Throughout History Emirati Figures Emirati Figures Revision Recognize what is meant Express the interest to Identify the recognise the symbols of Chant the national Recognize the Recognize the by the Ntional Day. participate in the National importance of national the Union. anthem of the country importance of the personality of sheikh https://en.islcollective.co Day celebration by day through ICT skills. in chorus. symobls of the Union Mohammad bin Rashid m/resources/printables/w drawing. https://www.mofa.gov. using ICT skills. Al maktoum. orksheets_doc_docx/uae_ ae https://www.thenational national_day/beginner- https://gulfnews.com/n .ae Revise all the work Emirati Figures Emirati Figures Geographical areas Geographical areas Geographical areas Geographical areas Geographical areas Revision Figure out the most Success of HH Sheikh Recognise the general Locate the neighbouring Find the location of the Describe the most keep the city where he Write End of Term outstanding initiatives of Mohammed bin Rashid Al shape of the United countries and water city where he lives, on significant features of lives clean. Assessments Sheikh Mohammad bin Maktoum Dubai. (through Arab Emirates map. bodies.Express his feelings the map of the Emirates. the city where he lives. Rashid Al maktoum. ICT Point the location of about living in the United skills.)http://www.sheikhm the United Arab Arab Emiartes. ohammed.ae Emirated on the map. GRADE 1 WEEK 1 WEEK 2 WEEK 3 WEEK 4 WEEK 5 WEEK 6 WEEK 7 WEEK 8 My Community My Community My Community My Community My Community My Community My Community Revision Name the mmbers of the Figure out the features of Compare the Emirati What makes a good UAE Appreciates the Recognise the Acquire daily life skills in Revise all the work Emirati family. -

The Use of Loanwords in Emirati Arabic According to Speakers' Gender, Educational Level, and Age International Journal of Appl

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au The Use of Loanwords in Emirati Arabic According to Speakers’ Gender, Educational Level, and Age Abdul Salam Mohamad Alnamer, Sulafah Abdul Salam Alnamer* College of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Al Ain, University of Science and Technology, P.O. Box: 64141 Al Ain, UAE Corresponding Author: Sulafah Abdul Salam Alnamer, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This study aims at identifying the loanwords commonly used in Emirati Arabic (EA), determining Received: February 04, 2018 their origins and identifying the reasons behind using them. It also investigates the impact of Accepted: April 12, 2018 gender, education, and age of speakers of EA on the use of loanwords. To meet these ends, a Published: July 01, 2018 questionnaire was designed and distributed among 90 speakers of EA who were then classified Volume: 7 Issue: 4 into three groups: 1) gender; females and males, 2) education; educated and uneducated, and Advance access: May 2018 3) age; young and old. The results show that female EA speakers, educated EA speakers, and young EA speakers use loanwords more than their counterparts in their specific groups. Moreover, the results show that EA speakers use loanwords of different origins like English, Persian, Hindi, Conflicts of interest: None and Turkish in addition to a few words of French, Italian, German, and Spanish. The study Funding: None discusses the possible reasons for these results and concludes with some recommendations for further research. Key words: Loanwords, Emirati Arabic, Gender, Educational Level, Age INTRODUCTION LITERATURE REVIEW One of the most observable and interesting results of the inter- Loanwords cultural contact among languages is the borrowing of words.