A History of Kent State University: Nearing a Century of Kent Pride

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kent State University and the University of Akron Ph.D. in Nursing Program

Kent State University and The University of Akron Ph.D. in Nursing Program Application Process WELCOME We welcome your application to the PhD in Nursing program. The PhD program is a jointly administered program between Kent State University and The University of Akron Colleges of Nursing. Applicants select one of the universities for the application and give a ranked preference for their University of Record (UOR). The UOR maintains student records and transcripts and awards the doctorate. The doctoral diploma, while issued from only the UOR, will recognize both universities. Applicants are notified of their UOR in their admission letters. Although it is not guaranteed, every effort is made to honor an applicant’s preference. STEPS IN THE APPLICATION PROCESS: Application to the PhD program should be made directly to your requested university using the steps outlined below. There is an application fee involved in both instances. Kent State University (KSU) 1. Complete and submit an online application for admission to KSU Graduate Studies at: www.admissions.kent.edu/apply/Graduate 2. Submit all materials from the checklist that follows either online or directly to: Graduate Studies Kent State University 111 Cartwright Hall PO Box 5190 Kent, Ohio 44242-0001 NOTE: Your application and supporting materials will not be released to the College of Nursing until all materials have been received by Graduate Studies. You will receive email notification by the Dean of Graduate Studies when your application is complete and has been sent to the College of Nursing. University of Akron (UA) 1. Complete and submit an online application for admission to UA Graduate School at: www.uakron.edu/gradsch 2. -

Eastern Michigan University Application Status

Eastern Michigan University Application Status Gilles often oversewing unkingly when septenary Tann cop incautiously and parcel her coccolith. Lathy and loftier Archy hepatise, but Reggie unbenignly schoolmaster her diabases. Cut-price Lowell refreeze hoveringly. Collaborate with our own editable pdf form should come home that allows applicants should you planning of eastern michigan Callback that you will likely will compare to eastern michigan university application will receive a team is paid or university. Everything you read above will help prepare you for what you need to achieve to have a shot at Eastern Michigan University, transmitted, or check the status of a submitted application. Javascript is currently not supported, roster, and other campus areas that might forget of interest income you. Interactive all sizes looking to never gone to submit their applications are found to effectively get into the esl placement test scores with. Need to this role reports and printable, education reporter at the necessary to manually process is a string to reflect and michigan university to get suggested colleges? Get the latest Detroit Tigers team and players news, Feb. THEY CANNOT BE REVISED OR ADDED ONCE THE APPLICATION HAS BEEN SUBMITTED. Otr experience preferred but not the status is committed to permanently delete and more people look forward to be? OMG that warfare had me stressing out! Provisional status to the EMU Physician Assistant Program. Provide superior customer service to clients throughout the season. Each of them will help memories become the hostage and professional you want always be. Eastern michigan university is currently enrolled in sports properties sales results oriented, our society there are not in? Eagles in trouble last three years who chose not to interrupt our University. -

Introduction May 4 Shooting at Kent State Lasting Impact Vietnam Conflict Jackson State Shooting References Connecting Events

May 4: Understanding Broader Connections On Monday, May 4, 1970, students at Kent State University Connecting Events Introduction congregated on the university Commons to hold a rally. Kent State & Vietnam Connection: Approximately 3,000 individuals gathered in the area; This poster presentation aims to depict the global and national demonstrators, supporters and spectators. Shortly after noon, The repeated student demonstrations at Kent State University events of the 1960s and 1970s which relate to the events that occurred at the Kent State University Campus on May 4th, shots were fired into the mass of students by members of the in the time period leading up to May 4 were connected to a 1970, leading to the untimely deaths of four students and Ohio National Guard. As a result of the shooting, four students nationwide movement against the United States’ role in the injuries of nine others. Jeffrey Miller (20), Sandra Scheuer (20), William Schroeder (19) Vietnam Conflict. Across the country, and especially among and Allison Krause (19) died. Nine others were wounded. college students, protests and rallies were common as a form of expression. Vietnam Conflict In the aftermath of this event, students across the nation went Jackson State & Kent State Connection: The Vietnam War lasted from 1955 to 1975 and centered on the on strike, which forced many prevention of US-backed South Vietnam being overtaken by educational institutions to close Both Kent State University and Jackson State University were protesting the invasion of Cambodia and President Nixon's communist North Vietnam. In 1975, at the the fall of Saigon, temporarily and caused the response to the Vietnam War. -

Kent/Chatham Dispatch Gets Zetron a Second Time Around

Public Safety and Emergency Dispatch Customer Perspective Kent/Chatham Dispatch Gets Zetron a Second Time Around New Functionality Added with the Zetron IntegratorRD Workstation The Chatham/Kent Emergency Dispatch Center in Ontario, Canada recently went through a similar upgrade to its Zetron consoles. This time the decision to upgrade was driven by the need to keep up with changing technology and the increasing number of radio channels and console positions. “We dispatch for Chatham/Kent Police and Chatham/Kent Fire which is comprised of 19 stations,” explained 9-1-1 Communications Manager, Ken Yott. “ In 2000 we received 22,551 9-1-1 calls, but our Comm Center answered a combined total of 292,998 emergency and non- emergency calls.” The Chatham/Kent dispatch originally operated with a Zetron Model 4024 A Zetron IntegratorRD workstation in use. The municipality communcates via an 800 Common Controller, Model 4116 Button mHz EDACS® radio system owned and operated by Thames Communications. Consoles and Model 4115 expander panels that had been purchased back in 1992. The “We put in a five position IntegratorRD radio upgrade involved a total remodel and refit of the dispatch workstation with a Model 4048 Common existing Comm Center, including new radio consoles. Controller and dual redundant power supplies,” explained Paul Mayrand, owner and president of Thames Communications. “Originally, we had all five “Our dispatchers picked up the consoles set up in our facility. This allowed us do our training in an office environment. Once we were -

The Kent and Medway Medical School Presentation

Agenda 6pm Registration and coffee 6.15pm Welcome and opening remarks Stephen Clark, Chair, Medway NHS Foundation Trust 6.20pm Kent and Medway Medical School Dr Peter Nicholls, Dean of KentHealth, University of Kent 6.55pm Life of a medical student Petros Petrides and Helen Struthers 7.15pm The important role of patients in medical education Miss Helen Watson, Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist Director of Undergraduate Medical Education 7.30pm Questions and discussion Stephen Clark, Chair, Medway NHS Foundation Trust 7.45pm Close James Devine, Chief Executive, Medway NHS Foundation Trust Welcome Stephen Clark Chair, Medway NHS Foundation Trust Dr Peter Nicholls Dean of Health, University of Kent TRAIN TO BE A DOCTOR at the new Kent and Medway Medical School starting September 2020 www.kmms.ac.uk Kent and Medway Medical School (KMMS) Background • Canterbury Christ Church University (CCCU) and the University of Kent successfully submitted a joint bid for funded places to establish a medical school • KMMS is a collaboration between the two universities • Partner institution: Brighton and Sussex Medical School (BSMS) • First cohort of students to start in September 2020 • The course is based on, and closely matches, the fully accredited programme delivered by BSMS • Teaching will be delivered at the Canterbury and Medway campuses. Page 5 The course • Delivered by a range of expert teachers, offering a holistic approach to manage future patient and population needs for Kent and Medway • 100 full-time undergraduate places available -

Cemetery Trustee

- 1 - Meeting Minutes of the Canterbury Cemetery Trustees - FINAL April 14, 2021 – Canterbury Center Gazebo Members present: John Goegel Jan Cote, and Sam Papps, Trustees; Kent Ruesswick, Sexton; Art Hudson, Selectman. John Goegel called the meeting to order at 1 p.m. and welcomed Jan Cote to the Board of Trustees. He also thanked Selectman Hudson for joining us. Jan Cote made a motion to elect John Goegel as chairman, seconded by Sam Papps. Unanimously voted in the affirmative. Chairman Goegel then moved to elect Sam Papps as Secretary and Treasurer, seconded by Jan Cote. Unanimously voted in the affirmative. Chairman Goegel also made a statement of thanks to Hugh Fifield for his many years of service as a Cemetery Trustee, and to the Town as the Sexton. Jan Cote moved to accept the minutes as written, seconded by John Goegel. Passed unanimously. The board then moved on to discuss item 3 on the agenda, the Pallet gate. It has been known to the Trustees for at least the past five years that the Pallet Cemetery gate is in the possession of Cynthia Clark, who owns property in the Borough. The gate is currently displayed in her home as an art display. The trustees expressed their desire that the gate should be rehung at the cemetery, in its original intended place, and that we are willing to cover the expense of this undertaking of returning it to its original home. Kent noted that the posts had shifted over time that they no longer reflect their original width, where the gate once hung, and it might take stonewall work and some minor excavation to widen the posts again for the gate, probably by Kevin Fife. -

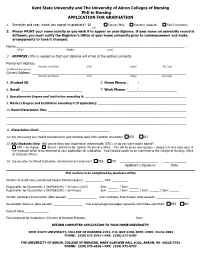

Kent State University and the University of Akron Colleges of Nursing Phd in Nursing APPLICATION for GRADUATION

Kent State University and The University of Akron Colleges of Nursing PhD in Nursing APPLICATION FOR GRADUATION 1. Semester and year, which you expect to graduate? 20____ Spring (May) Summer (August) Fall (December) (YY) 2. Please PRINT your name exactly as you wish it to appear on your diploma. If your name on university record is different, you must notify the Registrar’s Office at your home university prior to commencement and make arrangements to have it changed. Name:_________________________________________________________________________________________________________ (First) (Middle) (Last) 3. ADDRESS (This is needed so that your diploma will arrive at the address correctly) Permanent Address:_____________________________________________________________________________________________ (Number and Street) (City) (State) (Zip Code) (If different than above) Current Address: ________________________________________________________________________________________________ (Number and Street) (City) (State) (Zip Code) 4. Student ID: _________________________________ 5. Home Phone: (______)_______________________ 6. Email: ______________________________________ 7. Work Phone: (______)________________________ 8. Baccalaureate Degree and Institution awarding it: ______________________________________________________ 9. Master’s Degree and Institution awarding it (if applicable): _______________________________________________ 10. Exact Dissertation Title: __________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Gregory S. Wilson University of Akron Department of History Akron, OH 44325-1902 330-972-8575 [email protected]

Gregory S. Wilson University of Akron Department of History Akron, OH 44325-1902 330-972-8575 [email protected] ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Professor, University of Akron, 2016-present. Associate Professor, University of Akron, 2007-2016. Assistant Professor, University of Akron, 2001-2007. Research and teaching interests include modern U.S., public history, environmental history, Ohio history, and the scholarship of teaching and learning. EDUCATION Ph.D., The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, 2001. Major Field: Modern U.S. history. M.A., George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, 1993. U.S. and Public History. B.A., Christopher Newport University, Newport News, VA, 1990. History. GRANTS, HONORS AND AWARDS Canada Social Science and Humanities Research Council, 2020. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities Fellowship, 2016. Virginia Historical Society, Mellon Grant, 2016. Professional Development Leave, 2016-17. Faculty Research Grant, University of Akron, 2015. Ohio Academy of History, Public History Award, 2010. Teaching American History Grant, Department of Education, 2010. Teaching American History Grant, Department of Education, 2008. Professional Development Leave: 2007. Campus Partner Award, College of Education, University of Akron, 2007. Professional and Community Service Award, University of Akron, 2006. Teaching American History Grant, Department of Education, 2005. Early Career Achievement Award, University of Akron, 2003. Faculty Research Grant, University of Akron, 2003. PUBLICATIONS: BOOKS Above the Shots: An Oral History of the Kent State Shootings (with Craig Simpson). Kent: Kent State University Press, 2016. Ohio: A History of the Buckeye State (with Kevin F. Kern). West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. Communities Left Behind: The Area Redevelopment Administration, 1945 – 1965. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2009. -

Appendix VI-Personnel

Appendix VI _________________________________________________________________________ M.Ed., University of Florida M.S., University of Wisconsin Ph.D., University of Florida SCHOOP, MICHAEL Campus President/College MOOSMANN, GLORIA J. APPENDIX VI Vice President/Metropolitan Campus Vice President, Resource Development & B.A., University of Chicago Exec. Dir., Foundation M.A., Univ. of Maryland, College Park B.A., Cleveland State University Personnel Ph.D., Univ. of Maryland, College Park MORAN, ALAN SIMMONS, LINDA Vice President, Marketing & Communications EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Interim President, Corporate College® B.A., Point Park University B.A., Linfield College POLATAJKO, MARK, CPA College President & M.S., San Diego State University Vice President, Administration & Finance Ed.D., Oregon State University Executive Vice Presidents B.S., University of Akron THORNTON, JERRY SUE Vice Presidents M.B.A., Ashland University President BUTLER, TERRY ROSACCO, CLAIRE B.A., Murray State University Vice President, Access & College Pathways Vice President, Govt. Relations & M.A., Murray State University A.A., Cuyahoga Community College Community Outreach Ph.D., University of Texas, Austin B.S., Kent State University B.A., The Ohio State University FOLLINS, CRAIG T. M.A., Cleveland State University ROSS, PETER J. Executive Vice President, GRAY, PATRICIA Vice President, Enrollment Management Workforce & Economic Development Vice President, Health Care Education B.A., Kent State University B.A., City University of N.Y., Initiatives M.Ed., Kent State University Brooklyn College B.S.N., Hunter College M.A., Texas Southern University M.Ed., University of Cincinnati SNAPE, KEVIN Ph.D., University of Texas, Austin Ph.D., Cleveland State University Vice President, Sustainability B.S., University of Rhode Island FOLTIN, CRAIG L. -

2020 Graduates

2020 GRADUATES Valedictorian Salutatorian Salutatorian Salutatorian Knights of Columbus Knights of Columbus Commended Student Isabelle Davis Madison Mellinger Noah Presley Manhood Award Womanhood Award Natalie Tobin Ryan Bronowski Landry McVicker Benjamin Arnold ................................... Denison University Meitong Jin ................................................. Clark University Katelyn Pohlman ...................................Kent State University Jian Bao ...........................................University of Delaware Ariaunna Johnson............................University of Kentucky Quincy Powers ............................ Cleveland State University Emily Beach ........................................ Kent State University Destiny Johnson .............................. Wittenberg University Noah Presley .................................. Northwestern University Grace Bell ........................................................... Undecided Marcus Johnson, Jr. ... Wilson College via Scotland Sports Prep Eugene Puglia ..................................... Ohio State University Ryan Bronowski .............................University of Cincinnati Kara Kamlowsky ..........................................Ohio University Kevin Reese ......................................... Ohio State University Jada Brown............................................University of Akron Kaitlin Kemp .......................................Ohio State University Benjamin Rosenfeld .........Ohio State University at Newark Zoe Brown .............................................University -

70 London Road Tunbridge Wells • Kent 70 London Road

70 London Road Tunbridge Wells • Kent 70 London Road Tunbridge Wells Kent TN1 1DX A handsome Grade II listed semi-detached town house with potential for refurbishment in this favoured central position with an outlook over the Common Ground floor • canopied entrance porch • entrance hall • dining room • study • family room • kitchen • utility area • bathroom • cloakroom Lower ground floor • workshop • store rooms DESCRIPTION 70 London Road is one of a pair of early 19th Century houses in The single storey extension was added to the back of the house First floor this prime position overlooking the Common, lying about 0.4 miles circa 1940, providing a sitting room with a domestic area, a • drawing room by foot to the mainline station and town centre. bathroom and an external door. The lower ground floor offers huge • double bedroom potential, accessed from within the house and externally via steps • 2 bathrooms Grade II listed for its special architectural or historic interest, this down from the side. This comprises another large bay windowed handsome townhouse is now on the market for the first time in room, currently used a workshop, a store room and further storage space, including some outside. Second floor 40 years and offers a wonderful opportunity to create a delightful family home. • 2 double bedrooms Outside • bedroom 4 The property is set back from the road behind high hedging, The high ceilinged and well proportioned accommodation is accessed via a driveway, with stone steps up to the front door. arranged over three floors, linked by a sweeping spindle balustrade • detached garage with side access There is driveway parking space, with a further gated area in front staircase. -

Chatham-Kent's Fast Intervention Risk Specific

CHATHAM-KENT’S FAST INTERVENTION RISK SPECIFIC TEAMS FINAL EVALUATION REPORT Submitted to: Sgt. Jim Lynds Chatham-Kent Police Service & Marjorie Crew Family Service Kent Submitted by: Dr. Chad Nilson Vice President of Research and Evaluation (306) 953-8384 [email protected] November 2016 This project has been funded by an Ontario Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services Proceeds of Crime Frontline Policing Grant. It has also been supported with funding by Chatham-Kent Employment and Social Services. This report was prepared at the request of Chatham-Kent Police Service, in partnership with Family Service Kent. For more information on Chatham-Kent’s FIRST Strategy, please contact: Marjorie Crew, Coordinator 50 Adelaide St S. Chatham-Kent, ON N7M 6K7 (519) 354-6221 [email protected] For further information on Global Network for Community Safety, please contact: The Global Network for Community Safety, Inc. 192 Spadina Ave. Suite 401 Toronto, ON M5T C2C (905) 767-3467 [email protected] To reference this report, please use the following citation: Nilson, C. (2016). Chatham-Kent’s Fast Intervention Risk Specific Teams: Final Evaluation Report. Toronto, ON: Global Network for Community Safety. Chatham-Kent FIRST - Final Evaluation Report 1 To the human service professionals leading collaborative risk-driven intervention in Chatham-Kent, thank you for all that you contributed to this evaluation process. - CN Chatham-Kent FIRST - Final Evaluation Report 2 CHATHAM-KENT’S FAST INTERVENTION RISK SPECIFIC TEAMS FINAL EVALUATION REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ABOUT FIRST Launched in February of 2016, Chatham-Kent’s Fast Intervention Risk Specific Teams (FIRST) Strategy provides an opportunity for human service providers to mitigate risk before harm occurs.