Huang Yu-Ting.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEBRUARY 1998-$1.50 Official Publication of the Folk Dance

FEBRUARY 1998-$1.50 THE MAGAZINE OF INTERNATIONAL FOLK DANCING Official Publication of the Folk Dance Federation of California, Inc. Volume 55, No 2 February 1998 EDITOR & TABLE OF CONTENTS BUSINESS MGR, , Genevieve Pereira President's Message 3 FEBRUARY CONTRIBUTORS Festival of the Oaks 4 Barbara Bruxvoort EdKremers Sweetheart Festival 7 Max Horn Nadine Mitchell Statewide '98 8 Elsa Bacher Ruth Ruling Joyce Lissant Uggla George D. Marks International Cuisine 9 Larry Getchell Dancing on the Internet 10 FEDERATION OFFICERS - NORTH Council Clips . 11 Dance Descriptions: PRESIDENT Barbara Bruxvoort VICE PRESIDENT Mel vin Mann La Danse des Mouchoirs (Canada)... 13 TREASURER Page Masson Calendar of Events 15 REC. SECRETARY Laila Messer Events South 16 MEMBERSHIP Greg Mitchell PUBLIC RELATIONS Michael Norris Over 50 Years of Dancing 17 HISTORIAN , Craig Blackstone Dancers to Remember 18 PUBLICATIONS Nadine Mitchell Dance List by Council (Cont) 20 FEDERATION OFFICERS -SOUTH Classified Ads .........................23 PRESIDENT Marilyn Pixler VICEPRESIDENT Beverly Weiss On Our Cover TREASURER Forrest Gilmore REC. SECRETARY Carl Pilsecker Welcome to the Festival of the Oaks MEMBERSHIP CarolWall PUBLICITY Lois Rabb HISTORIAN Gerri Alexander NEWINFORMATTON: SUBSCRIPTIONRATE: $15 per year SUBMISSIONDEADLINE: $20 foreign & Canada Submission deadline for each issue BUSINESS OFFICE is the 25th of 2 months previous P.O.Box 1282 (i.e., March deadline would be Alameda, CA 94501 the 25th of January). Phone&FAX510-814-9282 Let's Dance (ISSN #0024-1253) is published monthly by the Folk Dance Federation of California, Inc., with the exception of the May/June and July/August issues, which are released each two-month period. Second class postage paid at Alameda and additional mailing offices. -

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy And

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Tsung-Hsin Lee, M.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Hannah Kosstrin, Advisor Harmony Bench Danielle Fosler-Lussier Morgan Liu Copyrighted by Tsung-Hsin Lee 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation “Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980” examines the transnational history of American modern dance between the United States and Taiwan during the Cold War era. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Carmen De Lavallade-Alvin Ailey, José Limón, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, and Alwin Nikolais dance companies toured to Taiwan under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. At the same time, Chinese American choreographers Al Chungliang Huang and Yen Lu Wong also visited Taiwan, teaching and presenting American modern dance. These visits served as diplomatic gestures between the members of the so-called Free World led by the U.S. Taiwanese audiences perceived American dance modernity through mixed interpretations under the Cold War rhetoric of freedom that the U.S. sold and disseminated through dance diplomacy. I explore the heterogeneous shaping forces from multiple engaging individuals and institutions that assemble this diplomatic history of dance, resulting in outcomes influencing dance histories of the U.S. and Taiwan for different ends. I argue that Taiwanese audiences interpreted American dance modernity as a means of embodiment to advocate for freedom and social change. -

Voices of Eternal Spring

Voices of Eternal Spring: A study of the Hingcun diau Song Family and Other Folk Songs of the Hingcun Area, Taiwan Submitted for PhD By Chien Shang-Jen Department of Music University of Sheffield January 2009 Chapter Four The Developmental Process and Historical Background of Hingcun Diau and Its Song Family Introduction The previous three chapters of this thesis detailed the three major systems of Taiwanese folksongs - Aboriginal, Holo and Hakka. Concentrating on the area of Hingcun, one of the primary cradles of Holo folksongs, these three chapters also explored how the geographical conditions, natural landscape, and historical and cultural background of the area influence local folksongs and what the mutual relations between these factors and the local folksongs are. Furthermore, the three chapters studied in depth not only the background, characteristics and cultural influences of each of the Hingcun folk songs but also local prominent folksong figures, major accompanying musical instruments, musical activities and so on. Chapter Four narrows the focus specifically to Hingcun diau and its song family. In this chapter, on the one hand, I examine carefully the changes in Hingcun diau and its song family activated from within a culture; on the other hand, I also pay attention to the changes in these songs caused by their contact with other cultures.1 In other words, in addition to a careful study of the origin, developmental process and historical background of Hingcun diau and its song family, I shall also dissect how the interaction of different ethnic groups, languages used in the area, political and economic factors, and various local cultures influence Hingcun diau and its song family, and what the mutual relations between the former factors and Hingcun diau and its song family are. -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 08, Issue 11, 2019: 18-24 Article Received: 01-10-2019 Accepted: 18-10-2019 Available Online: 12-11-2019 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v8i11.1754 A Close Analysis of the Characteristics of Lin Hwai-Min’s Dance Works Yiou Guo1, Jianhua Li2 ABSTRACT Lin Hwai-min, one of the most prestigious East Asian choreographers in the world, established the first contemporary dance company in Taiwan, the Cloud Gate Dance Theatre, which created a unique impression of Asian modern dance. Since his earliest dance works, unique balance is struck between literature and dance texts, mainland China and Taiwan, the East and the West, dance and humanities. This thesis begins from the perspectives of literary, eastern symbols, body language and music. It analyzes the artistic characteristics of Lin Hwai-min’s dance works, aiming to reveal the essence of choreographs. Keywords: Lin Hwai-min, Cloud Gate Dance Theatre, Choreography. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction On February 20th, 2013, Lin Hwai-min, a Taiwanese choreographer, was awarded the 2013 Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award for Lifetime Achievement by the American Dance Festival, one of the most authoritative institutions for contemporary dance in the world. The award celebrates choreographers who significantly contribute to contemporary dance, with previous recipients including Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, Trisha Brown, Pina Bausch, and William Forsythe. In awarding Mr. Lin, the American Dance Festival said, “Mr. Lin’s fearless zeal for the art form has established him as one of the most dynamic and innovative choreographers today.” (The welcome letter for Lin Hwai-min for 2013 Samuel H. -

Contra Costa Times

Posted on Wed, Oct. 29, 2003 Originality rules Cai's colorful style By Mary Ellen Hunt TIMES CORRESPONDENT ONE OF THE foremost Chinese dance companies in the Bay Area, Lily Cai Chinese Dance Company blends the color and vividness of traditional Chinese folk dances with Lily Cai's own style of movement centered from the core of the body. It is a technique similar to the tai chi-based methods used by Cloud Gate Dance Theater of Taiwan. San Francisco-based Lily Cai, which celebrates its 15th anniversary this year, brings its own special brand of dance theater to the stage with performances Nov. 14-15 at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. And like Cloud Gate's Lin Hwai-Min, Cai choreographs to a slower rhythm. Her 1997 work "Candelas," which is set to the Adagietto of Mahler's Fifth Symphony and which audiences will have a chance to see again on the November program, has an elegiac simplicity to it. But whereas Cloud Gate infuses its work with Western influences from Martha Graham to tanztheater, Cai consciously strives to keep her own style, derived purely from her own roots. "I have never trained at all (in modern dance)," Cai says. "It doesn't mean I don't want to learn other things, and I watch a lot of other groups' performances. But ideally I do not want to get into a modern dance style, because sooner or later, you become somebody else." Cai, who emigrated from China to the United States in 1983, began her career as a principal dancer in both ballet and folk dance at the Shanghai Opera House. -

Happy New Tear

DECEMBER 1997-$1.50 THE MAGAZINE OF INTERNATIONAL FOLK DANCING HAPPY NEW TEAR Official Publication of the Folk Dance Federation of California, Inc. Volume 54, No 10 December 1997 EDITOR & TABLE OF CONTENTS BUSINESS MGR. , Genevieve Pereira President's Message 3 DECEMBER CONTRIBUTORS Statewide '98 Institute 4 B arbara Bruxvoort EdKremers Wonderous Folkdance Cruise 5 Teddy Wolterbeek Larry Getchell Grace Nicholes 6 Ruth Ruling Loui Tucker PatLisin AlLisin Classified Ads 8 Council Clips 8 FEDERATION OFFICERS - NORTH Dance Description: PRESIDENT BarbaraBruxvoort Szot Madziar (Poland) 9 VICEPRESIDENT MelvinMann Take the Test................ 12 TREASURER Page Masson REC. SECRETARY Laila Messer Calendar of Events................ 14 MEMBERSHIP Greg Mitchell Events South 15 PUBLIC RELATIONS................... Michael Norris 1997 Let's Dance Index. 16 HISTORIAN Craig Blackstone PUBLICATIONS Nadine Mitchell Dance on the Internet 18 Milli Riba..........o.......o......o....................... 19 FEDERATION OFFICERS -SOUTH PRESIDENT Marilyn Pixler On Our Cover VICEPRESIDENT Beverly Weiss TREASURER Forrest Gilmore Happy Holidays REC. SECRETARY Carl Pilsecker from Let's Dance MEMBERSHIP CarolWall PUBLICITY Lois Rabb HISTORIAN................................. Gerri Alexander NEWINFORMATTON; SUBSCRIPTTONRATE: $15 per year SUBMISSIONDEADL1NE $20 foreign & Canada Submission deadline for each issue BUSINESS OFFICE: is the 25th of 2 months previous P.O.Box 1282 (i.e., March deadline would be Alameda, C A 94501 the 25th of January). Phone & FAX 510-814-9282 Let's Dance (ISSN #0024-1253) is published monthly by the Folk Dance Federation of California, Inc., with the exception of the May/June and July/August issues, which are released each two-month period. Second class postage paid at Alameda and additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to Folk Dance Federation of California, Inc., P.O. -

ATHE's 24Th Annual Conference August 3-6, 2010 Hyatt Regency

ATHE’s 24th Annual Conference August 3-6, 2010 Hyatt Regency Century Plaza Hotel, Los Angeles, CA | | ATHE’s 24th Annual Conference August 3-6, 2010 Hyatt Regency Century Plaza Hotel Los Angeles, CAlifornia Welcome to You are one of over 800 ATHE members, presenters, and guest artists who are gathered for the 24th annual Association for Theatre in Higher Education conference. “Theatre Alive:This Theatre, time we will dialogue Media, about theatre and and the Survival!”professoriate in the rapidly chang- ing 21st century, especially in light of developments in media, career preparation and professional development, and our roles in the redefinition of higher education. What more fitting sense of place for a conference examining possibilities and chal- lenges at the intersections of higher education, theatre and media than the City of Angeles. LA is a land of dreams and opportunities--the Entertainment Capital of the World--and a city of changing circumstances that also resonate where we all live and work. Congratulations to this year’s outstanding Conference Committee for crafting a per- fect sequel to last year’s conference, Risking Innovation. What are the emerging best practices that engage media in pedagogy, curricular design, and scholarship culmi- nating in publication or creative production? Pre-conference and conference events that explore this question are packed into four intense days. Highlights include: • Pulitzer Prize-winning Playwright Susan Lori-Parks’ Keynote Address • Opening Reception in the Exhibition Hall • THURGOOD with Laurence Fishburne • All-Conference Forum, “Elephants in the Curriculum: A Frank Discussion about Theatre in a Changing • Academic Landscape” • 12 Exciting Focus Group Debut Panels • Innovative multidisciplinary presentations • ATHE Awards Ceremony • ATHE Annual Membership Meeting • MicroFringe Festival • Professional Workshops with Arthur Lessac, Aquila Theatre’s Peter Meineck, Teatro Punto’s Carlos Garcia Estevez and Katrien van Beurden, arts activist Caridad Svich, and UCLA performance artist and composer Dan Froot. -

SPRING 2006 151 IX Festival Iberoamericano De Teatro De Bogotá

SPRING 2006 151 IX Festival Iberoamericano de Teatro de Bogotá (2004) Lucía Garavito El IX Festival Iberoamericano de Teatro de Bogotá (26 de marzo al 11 de abril 2004), "Un mundo para ver," rçalizó la edición de mayor envergadura en su historia gracias a la visión y la labor infatigable de Fanny Mikey, fundadora y promotora del evento.1 Logró el milagro de convocar la ayuda estatal y de la empresa privada para reunir los diez mil millones de pesos (tres millones de dólares) necesarios para subvencionar la participación de 38 compañías de América, Europa, Asia, Africa y Oceania que presentaron 617 funciones de sala y calle durante 17 días. Esta programación básica se vio enriquecida por la creación de una "Ciudad Teatro" en Corferias que contó con cinco compañías internacionales y diez nacionales, plazoleta de conciertos en la que se presentaron 27 grupos colombianos, salón de cuenteros, sala de exposiciones, 66 funciones infantiles y una Ventana Internacional de Artes Escénicas en la que participaron 53 directores y programadores. El festival incluyó además una serie de eventos especiales como seminarios (el lenguaje de la danza, la creación del personaje, la composición del espacio escénico), talleres (teatro documental, el entrenamiento corporal en Oriente y la meditación para la escena, improvisación, técnicas de circo, actuación en espacios no convencionales, dirección y actuación, voz e improvisación vocal, entre muchos otros), seminarios teóricos (el mundo de Shakespeare, crítica teatral, mise en scene, dramaturgia contemporánea -

65 Journal De L'adc Association Pour La Danse Contemporaine Genève

janvier — mars 2015 — adc / association pour la danse contemporaine — salle des eaux-vives — 82 - 84 rue des eaux-vives − 1207 genève 65 journal de l’adc association pour la danse contemporaine genève à l’affiche Noemi Lapzeson −− Olga Mesa −− Yann Marussich −− Anne Delahaye et Nicolas Leresche −− Nacera Belaza −− Frank Micheletti −− dossier Conventions, l’amour dure trois ans −− focus Noemi Lapzeson, transmettre la beauté P. P. 1207 Genève 2 / journal de l’adc n° 65 / janvier — mars 2015 journal de l’adc n° 65 / janvier — mars 2015 / 3 dossier focus 4 − 10 28 − 31 32 Conventions, l’amour Noemi Lapzeson, Créer pour dure trois ans la transmission de Noemi Lapzeson Les conventions de soutien la beauté, la beauté Vincent Barras livre un conjoint ville, canton et de la transmission texte subtil et personnel confédération sont, pour Alors qu’elle présente sur l’acte créatif. les onzes compagnies Noemi Lapzeson au côté de sa mère, Buenos Aires, 1947 sa création Variations Présentation de danse qui en bénéfi- Goldberg, un livre et un cient, un outil exemplaire. film témoignent du travail et extrait du livre Corinne Jaquiéry enquête pédagogique que Noemi de Marcela San sur un bilan aux échos Lapzeson a longuement Pedro contrastés. affiné avec ses élèves. à l’affiche carnet de bal histoires de corps édito 12 − 13 26 − 27 38 Please come Bach Variations Goldberg ce que font les un danseur se raconte Noemi Lapzeson danseurs genevois en trois mouvements : Sur la photographie ci-contre, Noemi Lapzeson a sept ans. Sa main sagement posée sur le grand harmonium, la et Norberto Broggini et autres nouvelles Amaury Réot petite Noemi regarde sa mère. -

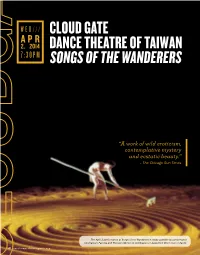

Songs of the Wanderers

WED 7:30PM WED/// ClOud gATE APR 2, 2014 dAnCE ThEATRE OF TAiwAn 7:30PM SOngS OF ThE WandERERS “A work of wild eroticism, contemplative mystery and ecstatic beauty.” – The Chicago Sun Times The April 2 performance of Songs of the Wanderers is made possible by performance benefactors Patricia and Thruston Morton in celebration of Jacqueline Zinn’s love of dance. 28 carolinaperformingarts.org WED 7:30PM APRil 2, 2014 Lin Hwai-min, choreography Ensemble Rustavi of Georgia, Georgian folk songs Chang Tsan-tao, lighting design Austin Wang, set design Taurus Wah, costume design Szu Chien-hua & Yang Cheng-yung, props design Premiere: November 4, 1994 National Theater, Taipei, Taiwan There is no happiness for him who does not travel, Rohita! Thus we have heard. Living in the society of men, the best man becomes a sinner... Therefore, wander! The feet of the wanderer are like the flower, his soul is growing and reaping the fruit; and all his sins are destroyed by his fatigues in wandering. Therefore, wander! The fortune of him who is sitting, sits; it rises when he rises; it sleeps when he sleeps; it moves when he moves. Therefore, wander! – The god Indra urges the life of the road upon a young man named Rohita in Aitareya Brahmana. PRogRAM & CAsT Prayer I Prayer III Wang Rong-yu Yu Chien-hung Holy River On the Road II Chen Tsung-chiao, Chen Mu-han, Hou Tang-li, Chiu I-wen, Hou Tang-li, Lee Tsung-hsuan, Hsiao Tzu-ping, Huang Hsiao-che, Huang Mei-ya, Su I-ping, Tsai Ming-yuan, Wong Lap-cheong Huang Pei-hua, Kuo Tzu-wei, Lee Tsung-hsuan, Lee Tzu-chun, -

Lewis Segal Collection of Dance and Theater Materials, 1902-2011; Bulk, 1970-2009

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8c24wzf No online items Lewis Segal Collection of Dance and Theater Materials, 1902-2011; Bulk, 1970-2009 Preliminary processing by Andrea Wang; fully processed by Mike D'Errico in 2012 in the Center for Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Jillian Cuellar; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. The processing of this collection was generously supported by Arcadia funds. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Lewis Segal Collection of Dance 1890 1 and Theater Materials, 1902-2011; Bulk, 1970-2009 Descriptive Summary Title: Lewis Segal Collection of Dance and Theater Materials Date (inclusive): 1902-2011; Bulk, 1970-2009 Collection number: 1890 Collector: Segal, Lewis Extent: 24 record cartons (24 linear ft.) Abstract: Lewis Segal is a performing arts critic who has written on various topics related to the performing arts, from ballet to contemporary dance and musicals. He began working as a freelance writer in the 1960s for a number of publications, including the Los Angeles Times, Performing Arts magazine, the Los Angeles Free Press, Ballet News, and High Performance magazine. He joined the staff of the Los Angeles Times in 1976. From 1996 to 2008 he held the full-time position of chief dance critic, writing full features and reviews on dance companies and performing arts organizations from around the world. -

With New Media Designed by TCS × DXARTS

with new media designed by TCS × DXARTS 2013.10. 31 Taipei National Concert Hall FOREWORD Singing is the earliest and most cherished music genre prac- Choral New ticed by human beings. Vocal art regains attention and value after hundred years of ever changing music trends. Capable Art: Songs of producing not only rich and broad textures but also lifelike mimicry of sounds, the nearly unlimited human voice is set of Unlimited free by composer’s imagination. With mutual assistance from electronic music, digital media and mechatronic installations, Sounds choral art will go beyond our imagination tonight. Human’s original musical performance type clashes with contemporary composers, and both contribute to the birth of Taipei Chamber Singers’ production “Music Unlimited VI—Void,” manifesting Taiwan’s rich creative energy. It is a delight to see TCS’s distinguished international ac- JU Tzong-Ching complishments since its establishment. The launch of “Music Chairman, Unlimited” project in 2006 not only expands the many pos- National Chiang Kai-Shek Cultural Center sibilities of vocal performance, but also provides a platform for contemporary choral music. “Music Unlimited VI—Void” is co-produced by the National Chiang Kai-Shek Cultural Center and Taipei Chamber Singers. For this production, we invite the Center for Digital Arts and Experimental Media (DXARTS) at the University of Washington (Seattle), outstanding compos- ers both in and out of Taiwan, dancers and theater artists to coordinate in the interdisciplinary performance of chorus and digital media, explore the great philosophical ideas in the essence of life, and portrays the oriental Zen aesthetics of one and none.