Reynolds Rip It up Intro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'hantologie Résiduelle, L'hantologie Brute, L'hantologie Traumatique*

Playlist Society Un dossier d’Ulrich et de Benjamin Fogel V3.00 – Octobre 2013 L’hantologie Trouver dans notre présent les traces du passé pour mieux comprendre notre futur Sommaire #1 : Une introduction à l’hantologie #2 : L’hantologie brute #3 : L’hantologie résiduelle #4 : L’hantologie traumatique #5 : Portrait de l’artiste hantologique : James Leyland Kirby #6 : Une ouverture (John Foxx et Public Service Broadcasting) L’hantologie - Page | 1 - Playlist Society #1 : Une introduction à l’hantologie Par Ulrich abord en 2005, puis essentiellement en 2006, l’hantologie a fait son D’ apparition en tant que courant artistique avec un impact particulièrement marqué au niveau de la sphère musicale. Évoquée pour la première fois par le blogueur K-Punk, puis reprit par Simon Reynolds après que l’idée ait été relancée par Mike Powell, l’hantologie s’est imposée comme le meilleur terme pour définir cette nouvelle forme de musique qui émergeait en Angleterre et aux Etats-Unis. A l’époque, cette nouvelle forme, dont on avait encore du mal à cerner les contours, tirait son existence des liens qu’on pouvait tisser entre les univers de trois artistes : Julian House (The Focus Group / fondateur du label Ghost Box), The Caretaker et Ariel Pink. C’est en réfléchissant sur les dénominateurs communs, et avec l’aide notamment de Adam Harper et Ken Hollings, qu’ont commencé à se structurer les réflexions sur le thème. Au départ, il s’agissait juste de chansons qui déclenchaient des sentiments similaires. De la nostalgie qu’on arrive pas bien à identifier, l’impression étrange d’entendre une musique d’un autre monde nous parler à travers le tube cathodique, la perception bizarre d’être transporté à la fois dans un passé révolu et dans un futur qui n’est pas le nôtre, voilà les similitudes qu’on pouvait identifier au sein des morceaux des trois artistes précités. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Scanned Image

INSIDE Singleschart, 6-7;Album chart,17; New Singles, 18; NewAlbums, 13; Airplay guide, 14-15; lndpendent Labels, 8; Retailing 5. June 28, 1982 VOLUME FIVE Number 12 65p RCA sets price Industry puts brave rises on both face on plunging LPs & singles RCAis implementing itsfirst wide- ranging increase in prices since January Summer disc sales 1981. Then its new 77p dealer price for singles sparked trade controversy but ALL THE efforts of the record industryfor the £s that records appear to be old the rest of the industry followed in due to hold down prices and generate excite-hat. People who are renting a VCR are course. ment in recorded music are meeting amaking monthly payment equivalent to With the new prices coming into stubbornly flat market. purchasing one LP a week," he said. effect on July 1, RCA claims now to be Brave faces are being worn around the Among the major companies howev- merely coming into line with other major companies but itis becominger, there is steadfast resistance to gloom. companies. clear that the business is in the middle of Paul Russell, md of CBS, puts the New dealer price for singles will be an even worse early Summer depressionproblem down to weak releases and is 85p (ex VAT) with 12 -inch releases than that of 1981. happy to be having success with Joan costing £1.49, a rise of 16p. On tapes The volume of sales mentioned by theJett, The Clash, Neil Diamond andWHETHER IT likes it or not, Polydorand albums the 3000 series goes from RB chart department shows a decline ofAltered Images with the prospect of bigis now heavy metal outfit Samson's£2.76 to £2.95, the 6000 series from between 20 and 30 percent over the samereleases from Judas Priest and REOrecord company. -

Resolution May/June 08 V7.4.Indd

craft Horn and Downes briefl y joined legendary prog- rock band Yes, before Trevor quit to pursue his career as a producer. Dollar and ABC won him chart success, with ABC’s The Lexicon Of Love giving the producer his fi rst UK No.1 album. He produced Malcolm McLaren and introduced the hitherto-underground world of scratching and rapping to a wider audience, then went on to produce Yes’ biggest chart success ever with the classic Owner Of A Lonely Heart from the album 90125 — No.1 in the US Hot 100. Horn and his production team of arranger Anne Dudley, engineer Gary Langan and programmer JJ Jeczalik morphed into electronic group Art Of Noise, recording startlingly unusual-sounding songs like Beat Box and Close To The Edit. In 1984 Trevor pulled all these elements together when he produced the epic album Welcome To The Pleasuredome for Liverpudlian bad-boys Frankie Goes To Hollywood. When Trevor met his wife, Jill Sinclair, her brother John ran a studio called Sarm. Horn worked there for several years, the couple later bought the Island Records-owned Basing Street Studios complex and renamed it Sarm West. They started the ZTT imprint, to which many of his artists such as FGTH were signed, and the pair eventually owned the whole gamut of production process: four recording facilities, rehearsal and rental companies, a publisher (Perfect Songs), engineer and producer management and record label. A complete Horn discography would fi ll the pages of Resolution dedicated to this interview, but other artists Trevor has produced include Grace Jones, Propaganda, Pet Shop Boys, Band Aid, Cher, Godley and Creme, Paul McCartney, Tina Turner, Tom Jones, Rod Stewart, David Coverdale, Simple Minds, Spandau Ballet, Eros Ramazzotti, Mike Oldfi eld, Marc Almond, Charlotte Church, t.A.T.u, LeAnn Rimes, Lisa Stansfi eld, Belle & Sebastian and Seal. -

At Powell Hall

GROUPS WELCOME AT POWELL HALL 2017 2018 GROUP SALES GUIDE SEASON slso.org/groupsI 314-286-4155 GROUPS ENJOY FIVE-STAR BENEFITS PERSONALIZED SERVICE Receive one-on-one, personalized service for all your group needs. From seat selection to performance suggestions to local restaurant recommendations, we’re ready to assist with planning your next visit to Powell Hall! SAVINGS Enjoy up to 20%* o the single ticket price when you bring 10 or more people. FREE BUS PARKING Parking, map and transportation information included with all group orders. PRIORITY SEATING Get the best seats for a great price! Group reservations can be made in advance of OUR FAMILY IS YOUR FAMILY public on-sale dates. PRE-CONCERT CONVERSATIONS Whether you’ve been part of the musical tradition or joining us for the first time, Even great music-making profits from an introduction. Enjoy FREE Pre-Concert we welcome you and your neighbors, friends, colleagues or students to experience Conversations before every SLSO classical concert. Music Director David Robertson the incomparable Musical Spirit of the second oldest orchestra in the country, and our guest artists participate in many of these conversations. your St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, in our beloved home of Powell Hall. Bring your group of 10 or more and save up to 20%. These musical oerings are just the start SPONSORED BY of making memories with us this upcoming season! THE SLSO SPECIALIZES IN HOSTING GROUPS: ENHANCE YOUR EXPERIENCE Corporations Employee Outings Schools + Universities Social + Professional Clubs SHUTTLE SERVICE Attraction + Performance Tour Groups Convenient transportation from West County is available for our Friday morning Senior + Youth Groups Coee Concerts. -

'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Glasgow School of Art: RADAR 'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir) David Sweeney During the Britpop era of the 1990s, the name of Mike Leigh was invoked regularly both by musicians and the journalists who wrote about them. To compare a band or a record to Mike Leigh was to use a form of cultural shorthand that established a shared aesthetic between musician and filmmaker. Often this aesthetic similarity went undiscussed beyond a vague acknowledgement that both parties were interested in 'real life' rather than the escapist fantasies usually associated with popular entertainment. This focus on 'real life' involved exposing the ugly truth of British existence concealed behind drawing room curtains and beneath prim good manners, its 'secrets and lies' as Leigh would later title one of his films. I know this because I was there. Here's how I remember it all: Jarvis Cocker and Abigail's Party To achieve this exposure, both Leigh and the Britpop bands he influenced used a form of 'real world' observation that some critics found intrusive to the extent of voyeurism, particularly when their gaze was directed, as it so often was, at the working class. Jarvis Cocker, lead singer and lyricist of the band Pulp -exemplars, along with Suede and Blur, of Leigh-esque Britpop - described the band's biggest hit, and one of the definitive Britpop songs, 'Common People', as dealing with "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

Manic Street Preachers Tornano Con Un Nuovo Disco, Intitolato Futurology, in Uscita L'8 Manic Street Preachers Luglio 2014

LUNEDì 28 APRILE 2014 A soli nove mesi di distanza dall'acclamato Rewind The Film (top 5 nel Regno Unito), undicesimo album da studio della band, i Manic Street Preachers tornano con un nuovo disco, intitolato Futurology, in uscita l'8 Manic Street Preachers luglio 2014. Futurology, il nuovo album, in uscita l'8 luglio. Registrati ai leggendari Hansa Studios di Berlino e al Faster, lo studio dei In concerto in Italia il 2 giugno 2014 al RocK In Manics a Cardiff, i tredici brani che compongono l'album vedono la band Idro di Bologna gallese in forma smagliante, addirittura esplosiva. Uno stacco netto rispetto al disco precedente, ma sempre all'insegna di uno stile inconfondibile. LA REDAZIONE Il primo singolo estratto è "Walk Me To The Bridge", dalle chiare influenze europee. In una recente conversazione con John Doran di Quietus, Nicky Wire ha parlato del testo del brano, che ha cominciato a prendere forma qualche anno fa. "Qualcuno penserà che la canzone contenga tanti riferimenti a Richey Edwards, ma in realtà parla del ponte di Øresund che collega la Svezia alla Danimarca. Tanto tempo fa, quando [email protected] attraversavamo quel ponte, stavo perdendo entusiasmo per le cose e SPETTACOLINEWS.IT pensavo di lasciare la band (il "fatal friend"). 'Walk Me To The Bridge' parla dei ponti che ti consentono di vivere un'esperienza extracorporea quando lasci un luogo per raggiungerne un altro". Secondo James Dean Bradfield, il brano è "una canzone ideale per i viaggi in auto, dal sapore squisitamente europeo e carica di tensione emotiva, con sintetizzatori in stile primi Simple Minds e un assolo di chitarra Ebow alla 'Heroes'". -

WXYC Brings You Gems from the Treasure of UNC's Southern

IN/AUDIBLE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR a publication of N/AUDIBLE is the irregular newsletter of WXYC – your favorite Chapel Hill radio WXYC 89.3 FM station that broadcasts 24 hours a day, seven days a week out of the Student Union on the UNC campus. The last time this publication came out in 2002, WXYC was CB 5210 Carolina Union Icelebrating its 25th year of existence as the student-run radio station at the University of Chapel Hill, NC 27599 North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This year we celebrate another big event – our tenth anni- USA versary as the first radio station in the world to simulcast our signal over the Internet. As we celebrate this exciting event and reflect on the ingenuity of a few gifted people who took (919) 962-7768 local radio to the next level and beyond Chapel Hill, we can wonder request line: (919) 962-8989 if the future of radio is no longer in the stereo of our living rooms but on the World Wide Web. http://www.wxyc.org As always, new technology brings change that is both exciting [email protected] and scary. Local radio stations and the dedicated DJs and staffs who operate them are an integral part of vibrant local music communities, like the one we are lucky to have here in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Staff NICOLE BOGAS area. With the proliferation of music services like XM satellite radio Editor-in-Chief and Live-365 Internet radio servers, it sometimes seems like the future EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Nicole Bogas of local radio is doomed. -

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO Mccormick 04 06 a Beginning, and an End 06 10 the Precursors: WILLIAM S

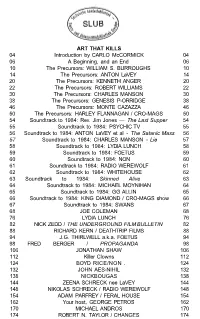

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO McCORMICK 04 06 A Beginning, and an End 06 10 The Precursors: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS 10 14 The Precursors: ANTON LaVEY 14 20 The Precursors: KENNETH ANGER 20 22 The Precursors: ROBERT WILLIAMS 22 30 The Precursors: CHARLES MANSON 30 38 The Precursors: GENESIS P-ORRIDGE 38 46 The Precursors: MONTE CAZAZZA 46 50 The Precursors: HARLEY FLANNAGAN / CRO-MAGS 50 54 Soundtrack to 1984: Rev. Jim Jones — The Last Supper 54 55 Soundtrack to 1984: PSYCHIC TV 55 56 Soundtrack to 1984: ANTON LaVEY et al - The Satanic Mass 56 57 Soundtrack to 1984: CHARLES MANSON - Lie 57 58 Soundtrack to 1984: LYDIA LUNCH 58 59 Soundtrack to 1984: FOETUS 59 60 Soundtrack to 1984: NON 60 61 Soundtrack to 1984: RADIO WEREWOLF 61 62 Soundtrack to 1984: WHITEHOUSE 62 63 Soundtrack to 1984: Skinned Alive 63 64 Soundtrack to 1984: MICHAEL MOYNIHAN 64 65 Soundtrack to 1984: GG ALLIN 65 66 Soundtrack to 1984: KING DIAMOND / CRO-MAGS show 66 67 Soundtrack to 1984: SWANS 67 68 JOE COLEMAN 68 76 LYDIA LUNCH 76 82 NICK ZEDD / THE UNDERGROUND FILM BULLETIN 82 88 RICHARD KERN / DEATHTRIP FILMS 88 94 J.G. THIRLWELL a.k.a. FOETUS 94 98 FRED BERGER / PROPAGANDA 98 106 JONATHAN SHAW 106 112 Killer Clowns 112 124 BOYD RICE/NON . 124 132 JOHN AES-NIHIL 132 138 NICKBOUGAS 138 144 ZEENA SCHRECK nee LaVEY 144 148 NIKOLAS SCHRECK / RADIO WEREWOLF 148 154 ADAM PARFREY / FERAL HOUSE 154 162 Your host, GEORGE PETROS 162 170 MICHAEL ANDROS 170 174 ROBERT N. -

Thank You Leadership Givers in the Spirit of Kaw Valley

THANK YOU LEADERSHIP GIVERS IN THE SPIRIT OF KAW VALLEY ASSOCIATION 2014 CAMPAIGN FOR INVESTING IN OUR COMMUNITY AND MAKING A PERSONAL COMMITMENT TO ADVANCE THE COMMON GOOD IN DOUGLAS COUNTY. This list of Leadership Givers Represents pledges received as of February 24, 2015. United Way of Douglas County THE ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE SOCIETY $10,000 or more United Way’s Tocqueville Society, created in 1984, Ethel & Raymond F. Rice Foundation is one of the world’s most prestigious institutions for Val & Beth Stella Membership is granted to individuals who contribute individuals who are passionate about improving $10,000 or more in special gifts annually. Larry & Peggy Johnson Thank you to these generous donors. peoples’ lives and strengthening communities. Plus 2 Anonymous Donors PATRIOT $5,000 HOMESTEADER $1,000 L. Susan Hadl Michael & Karen Roberts PIONEER $750 Bill & Jeanine Lienhard Virgil & Elaine Brady Dave & June Adams Kathleen Hall Phyllis & Stan Rolfe Mike & Tana Ahlen Mary Loveland Scott T. Coons David & Helen Alexander Nancy & Jeff Hambleton, DDS Marlesa A. Roney, PH.D. Lon & Lynn Akerberg Linda & Peter Luckey Monica Biernat David & Mary Kate Ambler Jerry & Michele Hammann Dr. & Mrs. Jan Roskam Mark & Susan Andersen Frank & Kallie Male Brian & Vickie Anderson Kelly & Tanja Harrison Robert & Ann Russell Pat & Debra McCandless & Chris Crandall Danny & Kimberly Anderson Katie & Ken Armitage Mike & Barbara Hartnett Richard & Phyllis Sapp Janet Perkins & Jeff Aube Kirk & Jeannie McClure Chris & Kaye Drahozal Larry R. Bakerink Bishop John Haslam Cathy Schneider Ken & Cheryl Audus Terry D. McEwen Mary Ruth Petefish Albert & Barbara Ballard Don & Carol Hatton James & Bonnie Schwartzburg Bill & Beverly Bartscher Michael & Christine McGrew Charitable Lead Trust Gene & Judy Bauer Adina M.