The Exploration of the Caucasus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Darkening Swiss Glacier Ice?” by Kathrin Naegeli Et Al

The Cryosphere Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2018-18-AC2, 2018 TCD © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Interactive comment Interactive comment on “Darkening Swiss glacier ice?” by Kathrin Naegeli et al. Kathrin Naegeli et al. [email protected] Received and published: 17 April 2018 ——————————————————————————— We would like to thank the referee 2 for this careful and detailed review. We appreciate the in-depth comments and are convinced that thanks to the respective changes, the manuscript will improve substantially. In response to this review, we elaborated the role of supraglacial debris in more detail by: (1) manually delineating medial moraines and areas where tributaries separated from the main glacier trunk and debris has become exposed to obtain a complete Printer-friendly version supraglacial debris mask based on the Sentinel-2 image acquired in August 2016, and (2) applying this debris mask to all data and, thus, to exclude areas with debris cover- Discussion paper age from all consecutive analyses. Additionally, we further developed the uncertainty assessment of the retrieved albedo values by providing more information about the C1 datasets used as well as their specific constraints and uncertainties that may result thereof in a separate sub-section in the methods section. Based on these revisions, TCD the conclusions will most likely be slightly adjusted, however, stay in line with the orig- inal aim of our study to investigate possible changes in bare-ice albedo in the Swiss Alps based on readily available Landsat surface reflectance data. Interactive comment Below we respond to all comments by anonymous referee 2. -

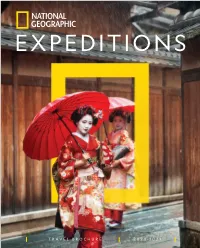

2 0 2 0–2 0 2 1 T R Av E L B R O C H U

2020–2021 R R ES E VE O BROCHURE NL INEAT VEL A NATGEOEXPE R T DI T IO NS.COM NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC EXPEDITIONS NORTH AMERICA EURASIA 11 Alaska: Denali to Kenai Fjords 34 Trans-Siberian Rail Expedition 12 Canadian Rockies by Rail and Trail 36 Georgia and Armenia: Crossroads of Continents 13 Winter Wildlife in Yellowstone 14 Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks EUROPE 15 Grand Canyon, Bryce, and Zion 38 Norway’s Trains and Fjords National Parks 39 Iceland: Volcanoes, Glaciers, and Whales 16 Belize and Tikal Private Expedition 40 Ireland: Tales and Treasures of the Emerald Isle 41 Italy: Renaissance Cities and Tuscan Life SOUTH AMERICA 42 Swiss Trains and the Italian Lake District 17 Peru Private Expedition 44 Human Origins: Southwest France and 18 Ecuador Private Expedition Northern Spain 19 Exploring Patagonia 45 Greece: Wonders of an Ancient Empire 21 Patagonia Private Expedition 46 Greek Isles Private Expedition AUSTRALIA AND THE PACIFIC ASIA 22 Australia Private Expedition 47 Japan Private Expedition 48 Inside Japan 50 China: Imperial Treasures and Natural Wonders AFRICA 52 China Private Expedition 23 The Great Apes of Uganda and Rwanda 53 Bhutan: Kingdom in the Clouds 24 Tanzania Private Expedition 55 Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia: 25 On Safari: Tanzania’s Great Migration Treasures of Indochina 27 Southern Africa Safari by Private Air 29 Madagascar Private Expedition 30 Morocco: Legendary Cities and the Sahara RESOURCES AND MORE 31 Morocco Private Expedition 3 Discover the National Geographic Difference MIDDLE EAST 8 All the Ways to Travel with National Geographic 32 The Holy Land: Past, Present, and Future 2 +31 (0) 23 205 10 10 | TRAVELWITHNATGEO.COM For more than 130 years, we’ve sent our explorers across continents and into remote cultures, down to the oceans’ depths, and up the highest mountains, in an effort to better understand the world and our relationship to it. -

Multi-Sensor Remote Sensing to Map Glacier Debris Cover in the Greater Caucasus, Georgia

Journal of Glaciology Multi-sensor remote sensing to map glacier debris cover in the Greater Caucasus, Georgia Iulian-Horia Holobâcă1,*, Levan G. Tielidze2,3 , Kinga Ivan1,*, 4 1 5 6 Article Mariam Elizbarashvili , Mircea Alexe , Daniel Germain , Sorin Hadrian Petrescu , Olimpiu Traian Pop7 and George Gaprindashvili4,8 *These authors contributed equally to this study. 1Faculty of Geography, GeoTomLab, Babeş-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania; 2Antarctic Research Centre, 3 Cite this article: Holobâcă I-H, Tielidze LG, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand; School of Geography, Environment and Earth Ivan K, Elizbarashvili M, Alexe M, Germain D, Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand; 4Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences, Petrescu SH, Pop OT, Gaprindashvili G (2021). Department of Geography, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia; 5Department of Geography, Multi-sensor remote sensing to map glacier Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada; 6Faculty of Geography, Babeş-Bolyai University, Cluj- debris cover in the Greater Caucasus, Georgia. Napoca, Romania; 7Faculty of Geography, GeoDendroLab, Babeş-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania and – Journal of Glaciology 67(264), 685 696. https:// 8Disaster Processes, Engineering-Geology and Geo-ecology Division, Department of Geology, National doi.org/10.1017/jog.2021.47 Environmental Agency, Tbilisi, Georgia Received: 18 August 2020 Revised: 5 April 2021 Abstract Accepted: 6 April 2021 First published online: 28 April 2021 Global warming is causing glaciers in the Caucasus Mountains and around the world to lose mass at an accelerated pace. As a result of this rapid retreat, significant parts of the glacierized surface Key words: area can be covered with debris deposits, often making them indistinguishable from the sur- Chalaati Glacier; coherence; debris cover; rounding land surface by optical remote-sensing systems. -

Mountaineering Ventures

70fcvSs )UNTAINEERING Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 v Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/mountaineeringveOObens 1 £1. =3 ^ '3 Kg V- * g-a 1 O o « IV* ^ MOUNTAINEERING VENTURES BY CLAUDE E. BENSON Ltd. LONDON : T. C. & E. C. JACK, 35 & 36 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. AND EDINBURGH PREFATORY NOTE This book of Mountaineering Ventures is written primarily not for the man of the peaks, but for the man of the level pavement. Certain technicalities and commonplaces of the sport have therefore been explained not once, but once and again as they occur in the various chapters. The intent is that any reader who may elect to cull the chapters as he lists may not find himself unpleasantly confronted with unfamiliar phraseology whereof there is no elucidation save through the exasperating medium of a glossary or a cross-reference. It must be noted that the percentage of fatal accidents recorded in the following pages far exceeds the actual average in proportion to ascents made, which indeed can only be reckoned in many places of decimals. The explanation is that this volume treats not of regular routes, tariffed and catalogued, but of Ventures—an entirely different matter. Were it within his powers, the compiler would wish ade- quately to express his thanks to the many kind friends who have assisted him with loans of books, photographs, good advice, and, more than all, by encouraging countenance. Failing this, he must resort to the miserably insufficient re- source of cataloguing their names alphabetically. -

Peaks & Glaciers 2019

JOHN MITCHELL FINE PAINTINGS EST 1931 3 Burger Calame Castan Compton 16, 29 14 6 10, 12, 23, 44, 46, 51 Contencin Crauwels Gay-Couttet Français 17, 18, 20, 22, 28, 46, 50 32 33 39 Gyger Hart-Dyke Loppé Mähly 17, 49, 51 26, 27 30, 34, 40, 43, 52 38 All paintings, drawings and photographs are for sale unless otherwise stated and are available for viewing from Monday to Friday by prior appointment at: John Mitchell Fine Paintings 17 Avery Row Brook Street Mazel Millner Roffiaen Rummelspacher London W1K 4BF 15 45 24 11 Catalogue compiled by William Mitchell Please contact William Mitchell on 020 7493 7567 [email protected] www.johnmitchell.net Schrader Steffan Tairraz Yoshida 9 48 8, 11, 19 47 4 This catalogue has been compiled to accompany our annual selling exhibition of paintings, Club’s annual exhibitions from the late 1860s onwards, there was an active promotion and 5 drawings and vintage photographs of the Alps from the early 1840s to the present day. It is the veneration of the Alps through all mediums of art, as artists tried to conjure up visions of snow firm’s eighteenth winter of Peaks & Glaciers , and, as the leading specialist in Alpine pictures, I am and ice – in Loppé’s words ‘a reality that was more beautiful than in our wildest dreams.’ With an proud to have handled some wonderful examples since our inaugural exhibition in 2001. In keeping increasingly interested audience, it is no surprise that by the end of the nineteenth century, the with every exhibition, the quality, topographical accuracy and diversity of subject matter remain demand for Alpine imagery far outstripped the supply. -

Peaks & Glaciers 2018

JOHN MITCHELL FINE PAINTINGS EST 1931 Willy Burger Florentin Charnaux E.T. Compton 18, 19 9, 32 33 Charles-Henri Contencin Jacques Fourcy Arthur Gardner 6, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 38, 47 16 11, 25 Toni Haller Carl Kessler Gabriel Loppé 8 20 21, 22, 24, 28, 30, 46 All paintings, drawings and photographs are for sale unless otherwise stated and are available for viewing from Monday to Friday by prior appointment at: John Mitchell Fine Paintings 17 Avery Row Brook Street London W1K 4BF Otto Mähly Carl Moos Leonardo Roda 36 34 37 Catalogue compiled by William Mitchell Please contact William Mitchell on 020 7493 7567 [email protected] www.johnmitchell.net Vittorio Sella Georges Tairraz II Bruno Wehrli 26 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 17 2 I am very pleased to be sending out this catalogue to accompany our One of the more frequent questions asked by visitors to these exhibitions in the gallery 3 is where do all these pictures come from? The short answer is: predominantly from the annual selling exhibition of paintings, drawings and vintage photographs countries in Europe that boast a good portion of the Alps within their borders, namely of the Alps. Although this now represents our seventeenth winter of France, Switzerland, Austria and Germany. Peaks & Glaciers , as always, my sincere hope is that it will bring readers When measured on a world scale, the European Alps occupy the 38th position in the same pleasure that this author derives from sourcing and identifying geographical size, and yet they receive over one and a half million visitors annually. -

Thegreat Journey Thegreat Journey

Sponsored by the University of Oklahoma Alumni Association THE GREAT JOURNEY THROUGH E UROPE The Netherlands u Germany u France u Switzerland cruising aboard the Exclusively Chartered Deluxe Amadeus Silver III July 8 to 18, 2020 Featuring the Glacier Express 10/19-1 Dear Alumni and Friends: Retrace the “Grand Tour,” an elite tradition undertaken by enlightened ladies and gentlemen of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries on this Great Journey through Europe. Traverse four countries and the western heart of the Continent on this carefully planned, exclusive itinerary. Join fellow OU alumni and friends, along with alumni and friends from other colleges and universities, as we discover the storied UNESCO World Heritage-designated Middle Rhine Valley, passing the hillside vineyards of the renowned Rheingau wine region, and meandering through the Netherlands’s expansive waterways flanked by polder land reclaimed from the North Sea. Experience three of the world’s great railway journeys and delight in the opportunity to experience six astounding UNESCO World Heritage sites. In Zermatt, marvel at the iconic Matterhorn as you travel aboard the Gornergrat Bahn, Switzerland’s oldest cog railway. Then, cross Switzerland’s mountainous backbone aboard the ingeniously engineered Glacier Express railway and spend two nights in lovely Lucerne in the Five-Star Hotel Schweizerhof, surrounded by glorious Alpine panoramas. From Lucerne, journey through the foothills of the Bernese Oberland Alps to Basel. Stop in medieval Bern, where the storybook Old Town is a celebrated UNESCO World Heritage site. Cruise aboard the exclusively chartered, deluxe Amadeus Silver III, one of the finest ships to ply the waters of Europe, from Basel to Amsterdam, the Netherlands. -

Digby & Strutt Families

MY ANCESTORS BEING THE HISTORY OF THE DIGBY & STRUTT FAMILIES BY LETTICE DIGBY PRIVATELY PRINTED BY SPOTTISWOODE, BALLANTYNE & CO. LTD. LONDON PREFACE So ME months of enforced idleness have given me great opportunities of thinking over the years that are passed. These memories are so radiantly happy that I felt con strained to try to chronicle them. In so doing I had occasion to refer to some of my ancestors, and this inspired me to collect all the information regarding them that I had at hand, in order that my nephews and nieces might have a simple chronicle of their lives. Some Digby papers and letters are in my possession, and I have been greatly helped by notes that my mother had made. The early Digby and early Strutt ancestors form a striking contrast-Digbys : courtiers, noblemen and states men ; Strutts : small yeoman farmers and artisans who, by their skill and integrity, became pioneers in industry and eminent citizens of Derby. Both families can claim at least one Fellow of the Royal Society. The Digby genealogical table has been compiled from an old printed pedigree entitled " A Genealogical Table of the Noble Family of Digby," which ends at Henry, 7th Baron and 1st Earl Digby, and from the Tree at Minterne, in the possession of the present Lord Digby, which was copied by the Honourable Theresa Mary Digby as a wedding present to my father. With few exceptions, the names on V both the Digby and Strutt tables are confined to those persons mentioned in the text. Many of the families were very large, and a full table, especially of the Digbys, would be too voluminous. -

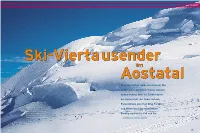

34 Aostatal V8

AOSTATAL UNTERWEGS Ski-ViertausenderSki-Viertausender im AostatalAostatal Frühjahrszeit ist Skihochtourenzeit. Wer in den Alpen ganz hoch hinaus will und zudem Genuss über die Schwierigkeit der Gipfel stellt, der findet auf den Auch wenn die Skihochtouren auf der Südseite des Monte Paradebergen zwischen Gran Paradiso Rosa gemeinhin als wenig schwierig gelten: Die Seraczone und Monte Rosa ein reichhaltiges unterhalb der Nordflanke der Parrotspitze signalisiert den Betätigungsfeld für Fell und Ski. Skibergsteigern, die Touren im Umkreis nicht zu unterschätzen. VON BERNHARD STÜCKLSCHWEIGER 34 35 AOSTATAL UNTERWEGS Bildliste oben: Das ai 1966: Der alte Postbus kommt zit- Zur optimalen Höhenanpassung besteigen Rifugio Vittorio Ema- ternd vor unserem Haus im hinteren wir tags darauf die 3609 Meter hohe La Tre- nuele (ganz links) wie MKleinsölktal zu stehen. Mit braunem senta, eine gemütliche Skitour mit knapp 900 das Rifugio Chabod Gesicht und strahlenden Augen, Norwegerpul- Höhenmetern. Ein einsamer schöner Gipfel, (Mitte) sind Stütz- lover und 32-fach verleimten Holzskiern steigt der neben dem Gran Paradiso ein Schattenda- punkte für die Tour mein Vater aus dem verstaubten Gefährt. End- sein führt. Der folgende Tag gehört aber ganz zum Gran Paradiso. lich ist er wieder zu Hause. Er kommt vom dem Gran Paradiso. Zweifellos ein erster Hö- Nach dem Aufstieg Aostatal. Während ich aufmerksam seinen Er- hepunkt in dieser Woche. Die ersten Stunden über weite Gletscher- zählungen zuhöre, von den 4000 Meter hohen ab dem Rifugio Emanuele sind meist in dem flächen rückt der fels- Bergen, den Steinböcken, Gämsen und Berg- nach Westen ausgerichteten Gletschertal bitter- durchsetzte Gipfel- bauern, die noch steilere Wiesen bewirtschaften kalt, aber dafür gewinnen wir über die ideal bereich näher (l.) und als wir in unserem Tal, keimt der Wunsch, auch geneigten und breiten Hänge recht flott an bald darauf steht man einmal dort in den Tälern und auf den Bergen Höhe. -

Recollections of Early Birmingham Members of the Alpine Club

RECOLLECTIONS OF EARLY BIRMINGHAM MEMBERS OF THE ALPINE CLUB. By WALTER BARROW. This is an attempt to give the present generation of climbers a sketch of some of the men of Birmingham and the Midlands who were prominent mountaineers in the last half of the 19th Century and with nearly all of whom I was personally acquainted. The Alpine Club the Mother of Alpine Clubs the world over was founded in England in 1857 (80 years ago). Three of the men of whom I am to speak were among the founders and original members of the Club. And one of these three was a climber with whose first ascent of the Wetterhorn in 1854 modern mountaineering as we know it is usually said to have begun. All these three were Birmingham men, so that we as Midlanders may well be proud of the part this City played in its early encouragement of our sport. But before I tell you of these and others whose names will be remembered as climbers I want to speak of a great Statesman of world wide reputation who became a member of the Alpine Club within 12 months of its foundation. Very few people know that JOSEPH CHAMBERLAIN, who did more than any man to make Birming ham what it has become, joined the Alpine Club along with his brother-in-law, John Arthur Kenrick in November, 1858. I must confess that I was 'surprised myself to find this out when search ing the early records of the Alpine Club. Chamberlain was then just 22 years of age and he had apparently had two holidays among the Swiss mountains. -

The British Caucasus Expedition 1986

129 The British Caucasus Expedition 1986 A.V. Saunders Plates 54-56 Mr Okano had been in the crevasse for eight days and nights when he was found. Although he was most inexpertly rescued, (A]86, 191-197, 198.1), he remained sufficiently grateful to send each member of the rescuing team a year's subscription to the National Geographical Magazine, and a copy of Mountains ofthe World in Japanese. Mountains ofthe World is a glorious volume, with excellent photographs of just about every mountain anyone has ever heard of. In the kitchen of a north London house my copy was on the table. Mick Fowler, Bert Symmonds, ¥aggie Urmston and myself were drooling over the shots of the Caucasian Peaks. Ushba in particular gripped our imagination. The picture showed a fierce double-headed Matterhorn. It looked as if an enormous Dolomite face had been welded to the N face of the Droites. At its highest, the W face rose 1600m above the glacier. Also scattered on the crowded table were Russian tourist pampWets, information sheets, and two volumes of Naimov's Central Caucasus in Russian. After a great deal of confusion, during which several peaks and chains of mountains were wrongfully ascribed to the Ushba area, it transpired that Ushba featured in a third, absent, volume of Naimov. I could see that our relationship with the Cyrillic alphabet was going to be a difficult one. Why go to Russia? It was Mick's idea. He wanted to go climbing for no more than a month, and yet he wanted somewhere more exploratory and with greater ethnic interest than Chamonix. -

The Netherlands Germany France Switzerland

Great Gator Escapes The Netherlands ◆ Germany ◆ France ◆ Switzerland cruising aboard the Exclusively Chartered DDeluxeeluxe M.S. AMMADEUSADEUS SIILVERLVER IIII featuring the GLLACIERACIER EXXPRESSPRESS June 15 to 25, 2017 Dear Gator Traveler: Join us on this Great Journey through Europe, the trip of a lifetime and an opportunity to retrace the traditional 17th-, 18th- and 19th-century “Grand Tour.” Travel through four countries and the western heart of the Continent on this carefully planned, unique University of Florida itinerary. Cruise the spectacular UNESCO World Heritage-designated Rhine Valley, passing the lush vineyards of its Rheingau wine region on the river’s bank, and through Holland’s picturesque waterways, surrounded by polder land reclaimed from the North Sea. Experience three of the world’s great railway journeys and visit four important UNESCO World Heritage sites. In Zermatt, marvel at the iconic Matterhorn as you travel aboard the Gornergrat Bahn, the country’s oldest cog railway. Then, cross the mountainous backbone of Switzerland aboard the celebrated, ingeniously engineered Glacier Express railway, and spend two nights in lovely Lucerne in the Five-Star HOTEL SCHWEIZERHOF LUZERN, where glorious Alpine panoramas surround you. From Lucerne, journey overland through the verdant, picturesque countryside of Switzerland to Basel. Stop in the medieval gem of Berne and in scenic Interlaken in the foothills of the magnifi cent Bernese Oberland Alps. The exclusively chartered, deluxe M.S. AMADEUS SILVER II, launched in 2015, provides our elegant accommodations en route from Basel to Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Port calls along the way include the lovely Alsatian city of Strasbourg, France, a fusion of both French and German cultures, and Rüdesheim, Koblenz, Cologne, and Mannheim for Heidelberg, Germany.