An Examination of the Concept of Intimacy in Radio Studies, Combining Mainstream and Non-Mainstream Theories and Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humour Summaries HU 144U Thelast Matchmaker by Willie Daly

Humour Summaries HU 144U TheLast Matchmaker by Willie Daly In his long career as a matchmaker, Willie Daly has helped hundreds of couples find happiness. With his unique blend of intuition, quiet wisdom and a small drop of cunning, Willie reveals the secret to finding true love, and shares the story of a life spent bringing people together in love and marriage.For centuries, Irish matchmakers have performed the vital service of bringing people together. It is a mysterious art, and the very best matchmakers have an almost magical quality to them. Willie Daly, whose father and grandfather were matchmakers before him, is the most famous of them all. The path to love can be heart-warming, hilarious, and sometimes hair-raising—and Willie is the perfect guide. For those still looking for romance, he also has some hard-earned, practical advice. Rich with characters, humour, drama and—of course—Guinness, Willie Daly regales us with some of his funniest and most touching matchmaking stories. HU 149U Sporting Gaffes Volume 1 & 2 by BBC Audio HU 150U The Goon Show Volume 13 by The Goon Show This 13th collection turns the clock back to the 1950s and the series' earliest surviving recordings. The episodes included are 'Harry Secombe Tracks Lo-Hing Ding', 'Handsome Harry Hunts for The Lost Drummer', 'The Failures of Handsome Harry Secombe', 'The Mystery of the Monkey's Paw', 'The Man Who Tried to Destroy London's Monuments', 'The Ghastly Experiments of Dr Hans Eidelburger', and 'The Missing Prime Minister'. Also featured are surviving extracts from 'The Search for the Bearded Vulture' and 'The Giant Bombardon'. -

REGISTER of SPONSORS (Tiers 2 & 5 and Sub Tiers Only)

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tiers 2 & 5 and Sub Tiers Only) DATE: 09-January-2017 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under Tiers 2 & 5 of the Points-Based System. It shows the organisation's name (in alphabetical order), the sub tier(s) they are licensed for, and their rating against each sub tier. A sponsor may be licensed under more than one tier, and may have different ratings for each tier. No. of Sponsors on Register Licensed under Tiers 2 and 5: 29,794 Organisation Name Town/City County Tier & Rating Sub Tier ?What If! Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 2 (A rating) Intra Company Transfers (ICT) @ Home Accommodation Services Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 5 (A rating) Creative & Sporting ]performance s p a c e [ london london Tier 5 (A rating) Creative & Sporting 01 Telecom Limited Brighton Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 0-two Maintenance London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1 Stop Print Ltd Ilford Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1 Tech LTD London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 10 Europe Limited Edinburgh Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 2 (A rating) Intra Company Transfers (ICT) 10 GROUP LTD T/A THE 10 GROUP LONDON Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 10 Minutes With Limited London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Page 1 of 1952 Organisation Name Town/City County Tier & Rating Sub Tier 1000heads Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1000mercis LTD London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 100Starlings Ltd -

Annual Report 2014-15

ANNUAL REPORT National Council for the 2014-15 Training of Journalists Contents Vital statistics 3 Chairman’s foreword 4 Chief executive’s review 5 Accreditation 2014-15 6 Qualifications 10 Gold standard students 12 Destinations of Diploma in Journalism students 2015 14 National Qualification in Journalism 15 Journalism Skills Conference 17 Student Council 19 Journalism Diversity Fund 21 Events, careers and publications 23 Business and finance review 25 Our people 27 Vital statistics 241 Certificate in Foundation Journalism units were submitted throughout 2014-15 18 candidates successfully completed the full foundation qualification 16,417 NCTJ examinations/assessments were taken throughout 2014-15 These comprised: 9,878 preliminary exams sat on course 1,176 portfolio assessments 658 were national exam sittings There were 4,543 shorthand exam sittings 1,548 students were enrolled to sit Diploma in Journalism exams on one of 80 accredited courses at 40 approved centres 388 candidates achieved the gold standard while on an accredited course 480 students were enrolled on non-accredited courses and sat NCTJ exams 382 candidates sat NCTJ exams in the national exam sittings 11 candidates successfully completed the Advanced Apprenticeship in Journalism The total number of NQJ exams sat was 820 237 trainees sat the National Qualification in Journalism – 230 reporters, 5 sports journalists and 2 photographers 168 passed the National Qualification in Journalism (NQJ) – 163 reporters, 4 sports journalists and 1 photographer Registrations in 2014-15 consisted of 225 reporters, 2 photographers and 68 apprentices 49 scheduled and in-house short training courses were run in 2014-15 3 Chairman’s report The Hollywood screenwriter William Goldman, who For years they addressed micro matters such as stories adapted that great story of journalism All the and by-lines rather than macro matters such as earning a President’s Men for cinema, suggested commercial living. -

RFI2013 Summary Date Received RFI20130001 Please Can You

Date RFI2013 Summary received Please can you provide with the average salary of local news presenter. Ie look north RFI20130001 01/01/2013 This FOI requested reasons for the BBC's wrong and hypothetical stance on the July 7 2005 bombings in London, when evidence clearly suggests that it was an inside job, the bombs were already planted under the trains...Why has the BBC not looked at the evidence which points to its cover-up and why is the BBC clinging on to its rehearsed storylines which are untrue, baseless and impossible RFI20130002 and don't make any sense? 02/01/2013 How much are the following members of the 'Match of the Day' team paid: Gary Lineker, Alan Hansen, Mark Lawrenson, Colin Murray, Robbie Savage, and Alan Shearer? - How much are the following athletics presenters and commentators paid: Steve Cram, Denise Lewis, Michael Johnson, Colin Jackson, Jonathan Edwards, Stuart Storie, Phil Dickinson, and John Rawling? and - Are the above presenters, commentators, and contributors paid on a salary RFI20130005 basis, or per appearance? 02/01/2013 How much did the BBC pay in total on TV panel guests for Question Time, QI and Mock The Week in 2012? What is each panellist paid to appear on Question Time in 2012? And, what was it in 2011? What is each panellist paid to appear on QI in 2012? And, what was it in 2011? What is each panellist paid to appear on Mock The Week in 2012? And, what was it in 2011? How much did the BBC pay in expenses in total for panellists on Questions Time in 2012? And, what did it pay out in 2011? How much -

The Record 2011/12

The Record 2011/12 The Record 2011/12 contents 5 Letter from the Warden 6 The Fellowship 9 Fellowship Elections and Appointments 9 Fellows and Lecturers Obituaries 11 JCR & MCR Elections 11 Undergraduate Scholarships 12 Matriculation 16 College Awards and Prizes 18 Academic Distinctions 20 Higher Degrees 21 Fellows’ Publications 26 Sports and Games 32 Clubs and Societies 35 The Chapel 36 Parishes Update 36 The Library and Archive 38 Old Members Obituaries 50 News of Old Members 3 Keble College: The Record 2011/12 letter from the warden This is the second, new style short letter from the Warden which reflects the changes in format of College publications introduced last year. Those changes have been very well received. The College has had a very good year. Perhaps it was the dismal weather in Trinity Term which encouraged our undergraduates to focus on their examinations, but whatever the reason I am delighted to report that a record number of forty finalists obtained Firsts (a third of the cohort) and there were some exceptional, prize-winning performances in Medicine, Engineering, Law, Computer Science, and Mathematics and Statistics. The research dimension of the College’s life continued to be enhanced by the development of our Advanced Studies Centre which arranged programmes of lectures and seminars in subjects as diverse as the treatment of stroke and neuro-degenerative disease and the interactions between elité culture and fairground puppet theatre in the seventeenth century. If 2011-12 didn’t quite repeat previous successes on field and river, we could be consoled by vicarious triumphs in the context of the Olympics; a Keble Old Member, Niels De Vos (Keble 1986), had an outstanding summer as Chief Executive of UK Athletics and another Old Member, Frank Cottrell-Boyce (Keble 1979), was closely involved in scripting the opening ceremony of the Games. -

17 July 2020 Page 1 of 9 SATURDAY 11 JULY 2020 Their Leader, the Duke of Monmouth's Forces Were Routed at Mrs Sopworth …

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 11 – 17 July 2020 Page 1 of 9 SATURDAY 11 JULY 2020 their leader, the Duke of Monmouth's forces were routed at Mrs Sopworth …. Gwen Cherrell Sedgemoor. Doreen/Gina …. Mia Soteriou SAT 00:00 Fear on 4 (b007jn6w) Sir Gervas slain, Reuben wounded and captive, Micah left the Three Thugs …. David Learner, Trevor Nichols and Jamie Series 2 field and turned his horse's head away from the west. Roberts Dreaming of Thee Starring Martyn Read, Patrick Troughton and James Bryce. Audio provided by the author. Lorna is obsessed with a certain dream, a dream which becomes The conclusion of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's historical novel set Director: Martin Jenkins a nightmare and threatens to become reality. to the backdrop of the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685. First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in August 1985. The Man in Black sets the scene... Micah ... Martyn Read SAT 07:30 Great Lives (b05077kv) Fear on 4 brings you more in a series of nerve-tinglers. Decimus Saxon .... Patrick Troughton Series 35 Written by Gwen Cherrell Reuben Lockarby .... James Bryce Mervyn King on Risto Ryti The Man In Black …. Edward de Souza Judge Jeffreys ... John Gabriel Mervyn King, former Governor of the Bank of England tells Lorna …. Karen Archer Master Helstrop .... Peter Wickham Matthew Parris why the life of the Prime Minister of Finland Cass …. Moir Leslie Master Tetheridge ... Stephen Thorne Risto Ryti was so remarkable. Cadenyer …. Dominic Rickhards Major Ogilvy .... Gregory de Polnay They are also joined by expert and biographer Martti Turtola. Eddie …. David Goudge Captain Steele .. -

12 December 2014 Page 1 of 18

Radio 4 Listings for 6 – 12 December 2014 Page 1 of 18 SATURDAY 06 DECEMBER 2014 Rosalind Shaw provide memories of their childhood growing up Newsjack, but got his first series in 2003 as part of the sketch and running riot in the Belfast Hills. team The Consultants. Jan's association with radio comedy SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b04stf7t) dates back to the early 1980s when she became the first-ever The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. And how has the area changed? Helen finds out how the Belfast female radio comedy producer, but became beloved of the Followed by Weather. Hills are now a destination for those hoping to enjoy walking Radio 4 audience for her work on Dead Ringers, which started and the views across the whole of the city. in 2000. Grace asks them about the atmosphere within the Radio Comedy department and within the BBC; they discuss SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b04t6yln) Presenter: Helen Mark the difference between topical comedy and satire, and whether Discontent and Its Civilizations Producer: Martin Poyntz-Roberts. the Radio 4 audience necessarily wants either; and they discuss the contribution a good sound engineer can make to a Episode 5 programme. SAT 06:30 Farming Today (b04t9j5z) These timely 'dispatches from Lahore, New York and London' Christmas Dinner Farming The Frequency of Laughter is presented by Grace Dent, a encompassing memoir, art and politics, collect the best essays journalist for The Independent, and is a BBC Radio Comedy of the award-winning author of The Reluctant Fundamentalist, A look at the farmers and producers who rear, grow and make production. -

Vol. 21, No. 1 Spring 2015

Green leaves The Journal of the Barbara Pym Society Vol. XXI, No. 1, Spring 2015 “A few green leaves can make such a difference.” — Miss Grundy, A Few Green Leaves North American Conference of the Barbara Pym Society (13–15 March 2015) by Isabel Stanley he Barbara Pym Society’s 17th annual tenses set the tone early in the novel. He noted North American Conference, which Barbara Tuchman's comment that the artist T Edward Hopper catches characters in an was held at the Barker Center, Harvard unresolved moment and noticed that Pym uses University, was well attended, with a capacity the same technique especially in scenes like crowd of 102 that included 27 first-time Marcia and Letty's retirement party. attendees as well as many long-time friends of the Society. Our dear archivist, Yvonne Raina Lipsitz continued the theme of Cocking, was sorely missed, but we look failure to connect in her paper. In focusing on the women's retirement party she highlighted forward to seeing her again under more the Deputy Assistant Director's pretentious felicitous weather conditions. bloviating about Letty and Marcia, about The Church of the Advent graciously whom he knew nothing. She shrewdly welcomed us back for our opening dinner Friday evening. The tables were decorated observed that part of Letty's failure to connect with bunches of spring flowers in small glass was due to other people's limited perspectives of her. milk bottles, which reappeared at Harvard the On Sunday morning Emily Stockard next day and were distributed as souvenirs examined ‘Pym among the Moderns’ in her after the conference. -

Happy 40Th Birthday BBC Radio

Happy 40th birthday BBC Radio ‘The Shipping Forecast’, ‘Six Continents’, Where did the old ‘Home Service’ stop and * * * * * ‘From our own correspondent’, ‘Breakfast on the new Radio 4 start? A change in name, Radio 4 was the BBC Home Service, and 3’, John Peel, ‘Alistair Cooke’, ‘Children’s that’s all. And Radio 1 forced by the pirates. may be again if in times of national Hour’, ‘Uncle Mac’, ‘The Navy Lark’, ‘Round the Horne’. Kenny Everett. But emergency all other channels are forced to ‘Hancock’s Half Hour’, ‘The Today most of all John Peel and ‘The Shipping close. If that happens I hope the BBC programme’, ‘The Proms’, John Peel, Forecast’. controllers follow the precedent set 40 years ‘Gardeners’ Question Time’, ‘The Brains ago and continue with an uninterrupted Trust’, ‘Round Britain Quiz’, ‘Take It From Neville Goodman schedule. In particular, I would emphasise Here’, ‘The News Quiz’, ‘I’m sorry I haven’t a * * * * * the necessity of continuing to broadcast clue’, ‘The Early Music Show’, ‘Late Our weekend rota, years ago, was shared ‘The Archers’, ‘The News Quiz’ and ‘I’m Junction’, ‘Front Row’, ‘The Shipping among six doctors from three practices in sorry I haven’t a clue’. BBC radios 1 –4 may Forecast’, ‘Just a minute’, ‘File on 4’, ‘Test adjacent areas. So, every sixth weekend saw be 40 years old, but the daddy of them all is Match Special’, ‘Pick of the Pops’, Jack de me car-bound for hours at a time as I Radio 4, at almost 70. Manio and John Humphreys — but most of crossed and re-crossed a large part of South It is almost impossible in this technological all John Peel and ‘The Shipping Forecast’. -

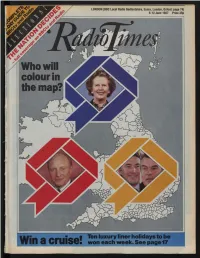

1987-Pages.Pdf

oimes 35 Marylebone High Street. London W1M 4AA Tel 01-580 5577 Published by Journals Division of BBC Enterprises Ltd Vol 253 No 3315 BBC Enterprises Ltd 1987 Editor Brian Gearing Deputy � Art Editor Brian Thomas Programme Editor Hugo Martin Features Editor Veronica Hitchcock Planning Editor Francesca Serpell ELECTION87 4 TheBattleground PeterSnow's 102 vital seats 6 First Results Who'llbe first past the polls? 8 HungParliaments AnthonyKing asks if they 're good for'What matters is the night' the constitution Anthony King, P 8 SHORTLY BEFORE 8.0 one Thursday evening have hitches: what matters is the night.' Tait is 10 Out of the House in April, some 150 employees put their clocks enthusiastic about the technology at his team's MPs ^gst who'IImiss forward by three hours and pretended it was 11 disposal: 'We're introducing some of the most tne jt^^^t^ Commonstouch June. BBCtv and Radio's full-scale General advanced equipment available - elections are 11 Carrott Election rehearsal was under way. ideally suited for computer animation.' ^^^^H� Jasper plays party games Of course, the results being processed by The names of every single candidate have ^^^H massed ranks of VDU weren't been in the General Election since 12 Grand Prix operators real; computer ^^^^Hf when returning officers read out voting figures, nominations closed on 27 May, and every result, ^^^^^m competition and successful candidates made grateful once declared, will be instantly available not 13 The Secret File speeches or gave triumphant interviews, all only to BBCtv and Radio studios but also to on Citizen K parts were in fact played by BBC reporters and everyone with a teletext set. -

Summer 2010 Bulletin Issue 101

Working for Quality and Diversity in Broadcasting Summer 2010 Bulletin Issue 101 Broadcasting Futures: Broadcasting in Scotland and Challenges and Opportunities Wales: the Future th Saturday, 16 October, 3pm - The Showroom, Sheffield Friday, 5 November 1 - 6pm Netherbow Theatre, Edinburgh in association In the present economic and Radio 4‘s with Edinburgh Napier and Stirling Universities political climate, the public Kaleidoscope, service broadcasters (BBC, will consider VLV‘s annual Scottish conference will ITV, Channel 4 and Five) face the contribution examine broadcasting issues in the two serious challenges. As part that the PSBs, devolved Nations. The key questions for the of Sheffield‘s Literary Festival, the BBC in conference include: how should Scottish and Off the Shelf, Rachel Cooke, particular, Rachel Cooke, Welsh broadcasting develop in the light of feature writer for the Observer make to democracy and the policy and public debates of recent years? and TV critic for the New cultural life of our nation. VLV What impact will the public spending cuts Statesman, and broadcaster President, Jocelyn Hay, will have on Welsh and Scottish broadcasting? Paul Allen, former presenter of chair. What are the implications for viewers and listeners? Culture Secretary Jeremy Hunt Channel 4 Chair to speak at Tuesday, 26 October, 6 - 8pm VLV Autumn Conference VLV Westminster Seminar, House of Commons, London SW1 Wednesday, 24 November Jeremy Hunt, the new Culture Secretary, will speak to VLV 10.15am - 3.30pm - Geological Society, Burlington House, London W1 members and guests at a VLV Westminster Evening Seminar in the House of Commons, on Tuesday, 26 October. Lord Burns, the new Chair of Channel 4, will give the keynote morning speech at Children at the Heart of the BBC’s Mission 11.30am at VLV‘s 27th Autumn Joe Godwin, Director of BBC Children’s in conversation with conference in London on 24 Professor Jeanette Steemers November. -

Pianofforte2014 LA.Indd JH Linked.Indd

8 Pianofforte | November 2014 Features THE LANG LANG EFFECT Launching a new piano series is always something to be excited about, but when one of the world’s leading concert pianists is involved, things go up a gear. Since the launch of the Lang Lang Piano Academy in September 2014, everyone’s been talking about the new technique series mastering the piano… impromptu performance and talk and styles of music. Pieces, exercises by Lang Lang himself. He chatted and studies infiltrate the pages, informally about the reasons for with lots of superlative practice and collaborating with Faber Music and preparation ideas from correct posture described it as a ‘lifelong dream’ to and hand positions to the importance produce a series of books such as of rhythm and hand coordination. these. His heart genuinely lies in music education, and for me this really is a Each chapter is preceded by a joy to behold. Lang Lang takes the ‘Message from Lang Lang’ and practice time and opportunity to highlight and features and technical advice is endorse the importance of playing the arranged in units, which appear with By Melanie Spanswick piano, and more importantly, playing corresponding advice based around The Classical Piano and it effectively. relevant pieces and exercises. All Music Education Blog pieces are assiduously examined, The books focus on how to play and a wealth of tips and practice and are not a piano method per se, suggestions are provided. It’s not “I was invited to attend the launch of as the sub-heading clearly states: unusual or indeed unexpected for Lang Lang’s new Piano Academy and ‘Technique, studies and repertoire for musicians to be influenced by other the series of piano books mastering the developing pianist’.