Read the 2011-12 Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hole a Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Going Down the 'Wabbit' Hole A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Barrie, Gregg Award date: 2020 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Gregg Barrie PhD Film Studies Thesis University of Dundee February 2021 Word Count – 99,996 Words 1 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Table of Contents Table of Figures ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Declaration ............................................................................................................................................ -

A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Timothy Semenza University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-6-2012 "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Timothy Semenza University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Semenza, Timothy, ""The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen" (2012). Honors Scholar Theses. 241. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/241 Semenza 1 Timothy Semenza "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Semenza 2 Timothy Semenza Professor Schlund-Vials Honors Thesis May 2012 "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Preface Choosing a topic for a long paper like this can be—and was—a daunting task. The possibilities shot up out of the ground from before me like Milton's Pandemonium from the soil of hell. Of course, this assignment ultimately turned out to be much less intimidating and filled with demons than that, but at the time, it felt as though it would be. When you're an English major like I am, your choices are simultaneously extremely numerous and severely restricted, mostly by my inability to write convincingly or sufficiently about most topics. However, after much deliberation and agonizing, I realized that something I am good at is writing about film. -

IDO Dance Sports Rules and Regulations 2021

IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations 2021 Officially Declared For further information concerning Rules and Regulations contained in this book, contact the Technical Director listed in the IDO Web site. This book and any material within this book are protected by copyright law. Any unauthorized copying, distribution, modification or other use is prohibited without the express written consent of IDO. All rights reserved. ©2021 by IDO Foreword The IDO Presidium has completely revised the structure of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations. For better understanding, the Rules & Regulations have been subdivided into 6 Books addressing the following issues: Book 1 General Information, Membership Issues Book 2 Organization and Conduction of IDO Events Book 3 Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines Book 4 Code of Ethics / Disciplinary Rules Book 5 Financial Rules and Regulations Separate Book IDO Official´s Book IDO Dancers are advised that all Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines are now contained in Book 3 ("Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines"). IDO Adjudicators are advised that all "General Provisions for Adjudicators and Judging" and all rules for "Protocol and Judging Procedure" (previously: Book 5) are now contained in separate IDO Official´sBook. This is the official version of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations passed by the AGM and ADMs in December 2020. All rule changes after the AGM/ADMs 2020 are marked with the Implementation date in red. All text marked in green are text and content clarifications. All competitors are competing at their own risk! All competitors, team leaders, attendandts, parents, and/or other persons involved in any way with the competition, recognize that IDO will not take any responsibility for any damage, theft, injury or accident of any kind during the competition, in accordance with the IDO Dance Sport Rules. -

The GPPA Report

THE GPPA Report SPRING 2018 THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE GREATER PITTSBURGH PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION A Letter from the President VICTOR BARBETTI, PHD, LICENSED PSYCHOLOGIST Dear GPPA Members, They will be joining existing Board members Drs. Teal Fitzpatrick (re- HOPE YOU ARE well and that you’re enjoying these warmer, elected), Nick Flowers, George sunnier days of late spring. Since I moved from the South to I Herrity, and William Hasek. Please Pittsburgh some 20 plus years ago, I have always enjoyed the join me in welcoming our newest distinct changes we experience here from season to season. The Board members. transitions are quite noticeable and bring with them anticipation As my time as Board President and excitement for the new. Change is good, I believe. It keeps winds down, I find myself reflect- us on our toes, and prevents us from settling too deep into our ing fondly over the past five years routines. and the work we’ve accomplished I’m excited to announce to the Membership that GPPA has re- together. Whether it’s honoring cently been granted Continuing Education status from the Ameri- a colleague through the Legacy can Psychological Association. During the last cycle (Fall 2016 Award program, or making new connections at a Networking - Spring 2017) the Board evaluated the feasibility of re-applying Fair, GPPA continues to facilitate opportunities for both new for CE granting privileges and, under the leadership of Dr. Teal and seasoned psychologists in the region. None of this would be Fitzpatrick, the CE Application committee has been very busy possible without the hard work of its members and the count- over the past year working to re-submit our application to APA. -

Deborah Barylski

DEBORAH BARYLSKI CASTING DIRECTOR (310) 314-9116 (h) SELECTED CREDITS (310) 795-2035 (c) FEATURE FILMS [email protected] PASTIME* Prod: Robin Armstrong, Eric Young Dir: R. Armstrong *Winner, Audience Award, Sundance MOVIES FOR TELEVISION ALLEY CATS STRIKE (Disney Cannel) Execs: Carol Ames, Don Safran, Michael Cieply Dir: Rod Daniel A PLACE TO BE LOVED (CBS) Exec. Producer: Beth Polson Dir: Sandy Smolan A MESSAGE FROM HOLLY (CBS) Exec. Producer: Beth Polson Dir: Rod Holcomb BACK TO THE STREETS OF SF (NBC) Exec. Producer: Diana Kerew, M. Goldsmith Dir: Mel Damski GUESS WHO'S COMING FOR XMAS? Exec. Producer: Beth Polson Dir: Paul Schneider TELEVISION: PILOT & SERIES *Winner, EMMY and Artios Awards for Casting for a Comedy Series, 2004 **Artios Award nomination SAINT GEORGE Execs: M.Williams,D. McFadzean,G.Lopez,M.Rotenberg Lionsgate/FX BACK OF THE CLASS Execs: Hugh Fink, Porter, Dionne, Weiner Nickelodeon DIRTY WORK (Won New Media Emmy) Execs: Zach Schiff-Abrams, Jackie Turnure, A. Shure Fourth Wall Studios THE MIDDLE Execs: Eileen Heisler, DeAnn Heline Warners/ABC UNTITLED DANA GOULD PROJECT Execs: D. Gould, Mike Scully, T. Lassally, D. Becky Warners/ABC THE EMANCIPATION OF ERNESTO Execs: Emily Kapnek, Wilmer Valderama 20th/Fox STARTING UNDER Exec. Bruce Helford/Mohawk Warners/Fox HACKETT Execs: Sonnenfeld, Moss, Timberman, Carlson Sony/FBC NICE GIRLS DON’T GET THE CORNER OFFICE. Execs: Nevins, Sternin, Ventimilia Imagine & 20th/ABC THE WAR AT HOME Exec. Rob Lotterstein, M.Schultheis, M.Hanel 20th/Warners/Fox KITCHEN CONFIDENTIAL Execs: D. Star, D. Hemingson, & New Line Fox/FBC THE ROBINSON BROTHERS Exec. Mark O’Keefe, Adelstein, Moritz,Parouse 20th/ORIGINAL/FBC ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT* Exec. -

Program Book

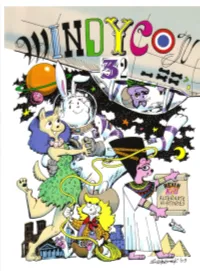

W Congratu lations to m Harry Turtledove WindyCon Guest of Honor HARRY I I if 11T1! \ / Fr6m the i/S/3 RW. ; Ny frJ' 11 UU bestselling author of TURTLEDOVE I Xi RR I THE SONS Of THE SOUTH Turtledove curious A of > | p^ ^p« | M| B | JR : : Rallied All I I II I Al |m ' Curious Notions In High Places 0-765-34610-9 • S6.95ZS9.99 Can. 0-765-30696-4 • S22.95/S30.95 Can. In paperback December 2005 In hardcover January 2006 In a parallel-world twenty-first century Harry Turtledove brings us to the twenty- San Francisco, Paul Goines and his father first century Kingdom ofVersailles, where must obtain raw materials for our timeline slavery is still common. Annette Klein while guarding the secret of Crosstime belongs to a family of Crosstime Traffic Traffic. When they fall under suspicion, agents, and she frequently travels between Paul and his father must make up a lie that two worlds. When Annette’s train is attacked puts Crosstime Traffic at risk. and she is separated from her parents, she wakes to find herself held captive in a caravan “Entertaining,. .Turtledove sets up of slaves and Crosstime Traffic may never a believable alternate reality with recover her. impeccable research, compelling characters and plausible details.” “One of alternate history’s authentic —Romantic Times BookClub Magazine, modern masters.” —Booklist three-star review rwr www.roi.com Adventures in Alternate History 'w&ritlh. our Esteemed Guests of Honor Harry Turtledove Bill Holbrook Gil G^x»sup<1 Erin Gray Jim Rittenhouse Mate s&nd Eouie jBuclklin Mark Osier Esther JFriesner grrad si xM.'OLl'ti't'o.de of additional guests ijrud'o.dlxxg Alex and JPliyllis Eisenstein Eric IF lint Poland Green axidL Erieda Murray- Jody Lynn J^ye and IBill Fawcett Frederik E»olil and ESlizzsJbetlx Anne Hull Tom Smith Gene Wolfe November 11» 13, 2005 Ono Weekend Only! Capricon 26 -Putting the UNIVERSE into UNIVERSITY Now accepting applications for Spring 2006 (Feb. -

Studies in Arts

Center for Open Access in Science Open Journal for Studies in Arts 2019 ● Volume 2 ● Number 2 https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojsa.0202 ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 OPEN JOURNAL FOR STUDIES IN ARTS (OJSA) ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 www.centerprode.com/ojsa.html [email protected] Publisher: Center for Open Access in Science (COAS) Belgrade, SERBIA www.centerprode.com [email protected] Editorial Board: Chavdar Popov (PhD) National Academy of Arts, Sofia, BULGARIA Vasileios Bouzas (PhD) University of Western Macedonia, Department of Applied and Visual Arts, Florina, GREECE Rostislava Todorova-Encheva (PhD) Konstantin Preslavski University of Shumen, Faculty of Pedagogy, BULGARIA Orestis Karavas (PhD) University of Peloponnese, School of Humanities and Cultural Studies, Kalamata, GREECE Meri Zornija (PhD) University of Zadar, Department of History of Art, CROATIA Responsible Editor: Goran Pešić Center for Open Access in Science, Belgrade Open Journal for Studies in Arts, 2019, 2(2), 35-70. ISSN ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 __________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS 35 From Figurative Painting to Painting of Substance – The Concept of an Artist Zdravka Vasileva 45 Spectacular Orientalism: Finding the Human in Puccini’s Turandot Francisca Folch-Couyoumdjian 57 Music and Environment: From Artistic Creation to the Environmental Sensitization and Action – A Circular Model Emmanouil C. Kyriazakos Open Journal for Studies in Arts, 2019, 2(2), 35-70. ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 __________________________________________________________________ -

Curriculum Vitae: Stephen Reysen Contact: Stephen Reysen Email: [email protected] Webpage

Curriculum Vitae: Stephen Reysen Contact: Stephen Reysen Email: [email protected] Webpage: https://sites.google.com/site/stephenreysen/ Texas A&M University-Commerce Department of Psychology and Special Education Commerce, TX 75429 Phone: (903) 886-5940 Fax: (903) 886-5510 Employment: 2015-Present Associate Professor, Texas A&M University-Commerce (TAMUC) 2009-2015 Assistant Professor, Texas A&M University-Commerce (TAMUC) Education: 2005-2009 University of Kansas (KU) Ph.D. Social Psychology, minor in Statistics 2003-2005 California State University, Fresno (CSUF) M.A. General Psychology, Emphasis: Social 1999-2003 University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) B.A. Intensive Psychology Editor: 2010-Present Journal of Articles in Support of the Null Hypothesis Co-Chair Social Sciences Area Committee: 2017-Present Fandom and Neomedia Studies Association, Social Sciences Studies Area Books: Edwards, P., Chadborn, D. P., Plante, C., Reysen, S., & Redden, M. H. (2019). Meet the bronies: The psychology of adult My Little Pony fandom. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. Reysen, S., & Katzarska-Miller, I. (2018). The psychology of global citizenship: A review of theory and research. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. [Nominated for International Society of Political Psychology Alexander George Book Award] [Nominated for Society for General Psychology William James Book Award] Plante, C. N., Reysen, S., Roberts, S. E., & Gerbasi, K. C. (2016). FurScience! A summary of five years of research from the International Anthropomorphic Research Project. Waterloo, Ontario: FurScience. Articles: Katzarska-Miller, I., & Reysen, S. (2019). Educating for global citizenship: Lessons from psychology. Childhood Education, 95(6), 24-33. Reysen, S., Plante, C. N., Roberts, S. E., & Gerbasi, K. -

List of Paraphilias

List of paraphilias Paraphilias are sexual interests in objects, situations, or individuals that are atypical. The American Psychiatric Association, in its Paraphilia Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM), draws a Specialty Psychiatry distinction between paraphilias (which it describes as atypical sexual interests) and paraphilic disorders (which additionally require the experience of distress or impairment in functioning).[1][2] Some paraphilias have more than one term to describe them, and some terms overlap with others. Paraphilias without DSM codes listed come under DSM 302.9, "Paraphilia NOS (Not Otherwise Specified)". In his 2008 book on sexual pathologies, Anil Aggrawal compiled a list of 547 terms describing paraphilic sexual interests. He cautioned, however, that "not all these paraphilias have necessarily been seen in clinical setups. This may not be because they do not exist, but because they are so innocuous they are never brought to the notice of clinicians or dismissed by them. Like allergies, sexual arousal may occur from anything under the sun, including the sun."[3] Most of the following names for paraphilias, constructed in the nineteenth and especially twentieth centuries from Greek and Latin roots (see List of medical roots, suffixes and prefixes), are used in medical contexts only. Contents A · B · C · D · E · F · G · H · I · J · K · L · M · N · O · P · Q · R · S · T · U · V · W · X · Y · Z Paraphilias A Paraphilia Focus of erotic interest Abasiophilia People with impaired mobility[4] Acrotomophilia -

2018 Juvenile Law Cover Pages.Pub

2018 JUVENILE LAW SEMINAR Juvenile Psychological and Risk Assessments: Common Themes in Juvenile Psychology THURSDAY MARCH 8, 2018 PRESENTED BY: TIME: 10:20 ‐ 11:30 a.m. Dr. Ed Connor Connor and Associates 34 Erlanger Road Erlanger, KY 41018 Phone: 859-341-5782 Oppositional Defiant Disorder Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Conduct Disorder Substance Abuse Disorders Disruptive Impulse Control Disorder Mood Disorders Research has found that screen exposure increases the probability of ADHD Several peer reviewed studies have linked internet usage to increased anxiety and depression Some of the most shocking research is that some kids can get psychotic like symptoms from gaming wherein the game blurs reality for the player Teenage shooters? Mylenation- Not yet complete in the frontal cortex, which compromises executive functioning thus inhibiting impulse control and rational thought Technology may stagnate frontal cortex development Delayed versus Instant Gratification Frustration Tolerance Several brain imaging studies have shown gray matter shrinkage or loss of tissue Gray Matter is defined by volume for Merriam-Webster as: neural tissue especially of the Internet/gam brain and spinal cord that contains nerve-cell bodies as ing addicts. well as nerve fibers and has a brownish-gray color During his ten years of clinical research Dr. Kardaras discovered while working with teenagers that they had found a new form of escape…a new drug so to speak…in immersive screens. For these kids the seductive and addictive pull of the screen has a stronger gravitational pull than real life experiences. (Excerpt from Dr. Kadaras book titled Glow Kids published August 2016) The fight or flight response in nature is brief because when the dog starts to chase you your heart races and your adrenaline surges…but as soon as the threat is gone your adrenaline levels decrease and your heart slows down. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Matriarch Elephant Vs. T-Rex by Roz Gibson 2020 Cóyotl Awards Winners Announced

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Matriarch Elephant vs. T-Rex by Roz Gibson 2020 Cóyotl Awards winners announced. The Cóyotl Awards are awarded annually by the Furry Writers' Guild to recognize excellence in anthropomorphic literature. This year there's a new award category! "Other Work", for things that exemplify the best in furry writing in a way that doesn't fit into the other categories. The winners and nominees for 2020, who were announced on May 8 on Twitch, are. Review: The Voyages of Cinrak the Dapper. The Voyages of Cinrak the Dapper is a collection of seven short stories written by A. J. Fitzwater centred around Cinrak, a lesbian, capybara pirate. It has a couple of strong elements as well as several weak points. I struggled with my thoughts as I read it and, in the end, I would say that, overall, I found it frustrating. I will start this review briefly talking about politics. It might seem like an unusual starting point but the introduction makes clear that the book is political and it touches on several hot button issues. Come for handsome, huggable Cinrak in a dapper three-piece, stay for her becoming a house-ship Mother to an enormous found family, the ethical polyamory, trans boy chinchilla, genderqueer rat mentor, fairy, and whale, drag queen mer, democratic monarchy, socialist pirates, and strong unionization. What I do like about the way politics is handled in this book, is that it is not set up as a conflict between opposing ideologies; the book presents its favoured way of seeing the world and just leaves it as that. -

Religious Studies (RELS) 1

Religious Studies (RELS) 1 RELS 013 Gods, Ghosts, and Monsters RELIGIOUS STUDIES (RELS) This course seeks to be a broad introduction. It introduces students to the diversity of doctrines held and practices performed, and art RELS 002 Religions of the West produced about "the fantastic" from earliest times to the present. The This course surveys the intertwined histories of Judaism, Christianity, fantastic (the uncanny or supernatural) is a fundamental category in and Islam. We will focus on the shared stories which connect these three the scholarly study of religion, art, anthropology, and literature. This traditions, and the ways in which communities distinguished themselves course fill focus both theoretical approaches to studying supernatural in such shared spaces. We will mostly survey literature, but will also beings from a Religious Studies perspective while drawing examples address material culture and ritual practice, to seek answers to the from Buddhist, Shinto, Christian, Hindu, Jain, Zoroastrian, Egyptian, following questions: How do myths emerge? What do stories do? What Central Asian, Native American, and Afro-Caribbean sources from is the relationship between religion and myth-making? What is scripture, earliest examples to the present including mural, image, manuscript, and what is its function in creating religious communities? How do film, codex, and even comic books. It will also introduce students to communities remember and forget the past? Through which lenses and related humanistic categories of study: material and visual culture, with which tools do we define "the West"? theodicy, cosmology, shamanism, transcendentalism, soteriology, For BA Students: History and Tradition Sector eschatology, phantasmagoria, spiritualism, mysticism, theophany, and Taught by: Durmaz the historical power of rumor.