Mid-Term Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

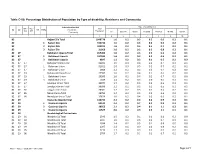

Table C-09: Percentage Distribution of Population by Type of Disability, Residence and Community

Table C-09: Percentage Distribution of Population by Type of disability, Residence and Community Administrative Unit Type of disability (%) UN / MZ / Total ZL UZ Vill RMO Residence WA MH Population Community All Speech Vision Hearing Physical Mental Autism 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 82 Rajbari Zila Total 1049778 1.6 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.6 0.2 0.1 82 1 Rajbari Zila 913736 1.6 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.6 0.2 0.1 82 2 Rajbari Zila 104074 1.6 0.2 0.4 0.1 0.7 0.2 0.1 82 3 Rajbari Zila 31968 2.0 0.2 0.5 0.2 0.8 0.3 0.1 82 07 Baliakandi Upazila Total 207086 1.6 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.6 0.2 0.1 82 07 1 Baliakandi Upazila 197189 1.6 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.6 0.2 0.1 82 07 3 Baliakandi Upazila 9897 1.3 0.2 0.3 0.1 0.5 0.3 0.0 82 07 17 Baharpur Union Total 34490 1.9 0.3 0.4 0.2 0.7 0.2 0.1 82 07 17 1 Baharpur Union 31622 2.0 0.3 0.5 0.2 0.7 0.2 0.1 82 07 17 3 Baharpur Union 2868 1.2 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.4 0.3 0.0 82 07 19 Baliakandi Union Total 27597 1.6 0.2 0.4 0.1 0.6 0.2 0.0 82 07 19 1 Baliakandi Union 20568 1.6 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.7 0.2 0.0 82 07 19 3 Baliakandi Union 7029 1.4 0.2 0.3 0.0 0.5 0.3 0.1 82 07 47 Islampur Union Total 30970 1.7 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.6 0.3 0.1 82 07 57 Jamalpur Union Total 30096 1.2 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.1 82 07 66 Jangal Union Total 20301 1.2 0.2 0.3 0.1 0.4 0.2 0.1 82 07 85 Narua Union Total 25753 1.4 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.6 0.2 0.1 82 07 95 Nawabpur Union Total 37879 1.6 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.6 0.2 0.1 82 29 Goalanda Upazila Total 112732 2.4 0.2 0.6 0.2 0.9 0.3 0.1 82 29 1 Goalanda Upazila 82542 2.4 0.2 0.7 0.2 0.9 0.3 0.1 82 29 2 Goalanda Upazila 18663 2.1 0.2 0.4 0.1 1.1 0.3 0.1 82 29 3 Goalanda -

Esdo Profile 2021

ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) ESDO PROFILE 2021 Head Office Address: Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) Collegepara (Gobindanagar), Thakurgaon-5100, Thakurgaon, Bangladesh Phone:+88-0561-52149, +88-0561-61614 Fax: +88-0561-61599 Mobile: +88-01714-063360, +88-01713-149350 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Dhaka Office: ESDO House House # 748, Road No: 08, Baitul Aman Housing Society, Adabar,Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-58154857, Mobile: +88-01713149259, Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd 1 ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) 1. BACKGROUND Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) has started its journey in 1988 with a noble vision to stand in solidarity with the poor and marginalized people. Being a peoples' centered organization, we envisioned for a society which will be free from inequality and injustice, a society where no child will cry from hunger and no life will be ruined by poverty. Over the last thirty years of relentless efforts to make this happen, we have embraced new grounds and opened up new horizons to facilitate the disadvantaged and vulnerable people to bring meaningful and lasting changes in their lives. During this long span, we have adapted with the changing situation and provided the most time-bound effective services especially to the poor and disadvantaged people. Taking into account the government development policies, we are currently implementing a considerable number of projects and programs including micro-finance program through a community focused and people centered approach to accomplish government’s development agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN as a whole. -

34418-023: Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources

Semiannual Environmental Monitoring Report Project No. 34418-023 December 2018 Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources Planning and Management Project - Additional Financing Prepared by Bangladesh Water Development Board for the People’s Republic of Bangladesh and the Asian Development Bank. This Semiannual Environmental Monitoring Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Semi-Annual Environmental Monitoring Report, SAIWRPMP-AF, July-December 2018 Bangladesh Water Development Board SEMI-ANNUAL ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING REPORT [Period July – December 2018] FOR Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources Planning and Management Project- Additional Financing Project Number: GoB Project No. 5151 Full Country Name: Bangladesh Financed by: ADB and Government of Bangladesh Prepared by: Bangladesh Water Development Board, Under Ministry of Water Resources, Govt. of Bangladesh. For: Asian Development Bank December 2018 Page | i Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... ii Executive -

Esdo Profile

ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) ESDO PROFILE Head Office Address: Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) Collegepara (Gobindanagar), Thakurgaon-5100, Thakurgaon, Bangladesh Phone:+88-0561-52149, +88-0561-61614 Fax: +88-0561-61599 Mobile: +88-01714-063360, +88-01713-149350 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Dhaka Office: ESDO House House # 748, Road No: 08, Baitul Aman Housing Society, Adabar,Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-58154857, Mobile: +88-01713149259, Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd 1 Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) 1. Background Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) has started its journey in 1988 with a noble vision to stand in solidarity with the poor and marginalized people. Being a peoples' centered organization, we envisioned for a society which will be free from inequality and injustice, a society where no child will cry from hunger and no life will be ruined by poverty. Over the last thirty years of relentless efforts to make this happen, we have embraced new grounds and opened up new horizons to facilitate the disadvantaged and vulnerable people to bring meaningful and lasting changes in their lives. During this long span, we have adapted with the changing situation and provided the most time-bound effective services especially to the poor and disadvantaged people. Taking into account the government development policies, we are currently implementing a considerable number of projects and programs including micro-finance program through a community focused and people centered approach to accomplish government’s development agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN as a whole. -

This Situation Report Report Is Prepared by DMIC, CDMP II

Issue: 01 It covers the period from: Sat, 14 Sep 2013 : 1200 to Sun, 15 Sep 2013 : 1400 Hazards 1. Flood 2. Flash Flood Areas at risk: Jamalpur, Rajshahi, Gaibandha, Kurigram, Sirajganj, Faridpur, Rajbari, Mymensing, Chandpur. Flood Situation Overview The Padma, the Brahmaputra, the Jamuna, the Ganges and the Meghna Rivers are in falling trend. The Kobadak at Jhikargacha is flowing above its respective danger level by 51 cm recorded today at 0:600 AM. The Brahmaputra-Jamuna, the Ganges-Padma and the Meghna may likely to fall in next 72 hours. Flood Situation in places of Gaibandha, Kurigram, Bogra, Serajganj, Jamalpur, Manikganj, Munshiganj, Rajbari & Faridpur may likely to improve in next 72 hours. [Source: FFWC, Last updated on Sep 15, 2013] Water Level Water level recorded during last 24 hrs ending at 06:00 AM today is: Rise(+)/ Above Danger Rivers Name Station name Fall(-) cm Level (cm) Kobadak Jhikargacha + 00 + 51 Rainfall Station Name Rainfall in mm Station Name Rainfall in mm Rangamati 35.0 Chittagong 30.0 General River Condition Monitored stations 73 Steady 02 Rise 08 Not reported 01 Fall 60 Stations Above danger level 01 [Source: FFWC, BWDB – www.ffwc.gov.bd ; Data Date: Sep 15, 2013] Page 1 of 3 DMIC is the information hub of the MoDMR for risk reduction, hazard early warnings and emergency response and recovery activities. District wise Flood Situation Jamalpur: 12 unions of Islampur upazila, 6 unions of Dewanganj upazila and 4 unions of Melandaha upazila have been inundated. 107500 peoples of 20100 families and 1549 households (partially) have been affected. -

Russell's Viper (Daboia Russelii) in Bangladesh: Its Boom and Threat To

J. Asiat. Soc. Bangladesh, Sci. 44(1): 15-22, June 2018 RUSSELL’S VIPER (DABOIA RUSSELII) IN BANGLADESH: ITS BOOM AND THREAT TO HUMAN LIFE MD. FARID AHSAN1* AND MD. ABU SAEED2 1Department of Zoology, University of Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh 2 555, Kazipara, Mirpur, Dhaka-1216, Bangladesh Abstract The occurrence of Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii Shaw and Nodder 1797) in Bangladesh is century old information and its rarity was known to the wildlife biologists till 2013 but its recent booming is also causing a major threat to human life in the area. Recently it has been reported from nine districts (Dinajpur, Chapai Nawabganj, Rajshahi, Naogaon, Natore, Pabna, Rajbari, Chuadanga and Patuakhali) and old records revealed 11 districts (Nilphamari, Dinajpur, Rangpur, Chapai Nawabganj, Rajshahi, Bogra, Jessore, Satkhira, Khulna, Bagerhat and Chittagong). Thus altogether 17 out of 64 districts in Bangladesh, of which Chapai Nawabganj and Rajshahi are most affected and 20 people died due to Russell’s viper bite during 2013 to 2016. Its past and present distribution in Bangladesh and death toll of its bites have been discussed. Its booming causes have also been predicted and precautions have been recommended. Research on Russell’s viper is deemed necessary due to reemergence in deadly manner. Key words: Russell’s viper, Daboia russelii, Distribution, Boom, Panic, Death toll Introduction Two species of Russell’s viper are known to occur in this universe of which Daboia russelii (Shaw and Nodder 1797) is distributed in Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka (www.reptile.data-base.org); while Daboia siamensis (Smith 1917) occurs in China, Myanmar, Indonesia, Thailand, Taiwan and Cambodia (Wogan 2012). -

Local Government Engineering Department Office of the Executive Engineer

Government of The People’s Republic of Bangladesh Local Government Engineering Department Office of the Executive Engineer Rajbari www.lged.gov.bd ‡kL nvwmbvi g~jbxwZ MÖvg kn‡ii DbœwZ Reference : 46.02.8200.000.99.055.20-630 Dated : 15-02-2021 e-Tender Notice-32/2020-2021 e-Tender is invited in the National e-GP System Portal (http//www.eprocure.gov.bd) for the Procurement of following works: Tender/ Last Date and Sl. Proposal Time for Procure No. e-Tender Document last Tender/Proposal Package No Name of Work ment ID selling / Security Method downloading Submission : Date and Time: Part-1 Estimate for Improvement of Boaromollika village Dilip More to Duchundangi Gram road at ch.00m-1000m under Baliakandi upazila District Rajbari.Part-2 Estimate for construction of 2 nos MSRDP/R/20-21/ 07-Mar-2021 08-Mar-2021 625mm600mm drainage culvert u-drain on 546099 LTM 1 BC/120 17:00 12:30 Boaromollika village Dilip More to Duchundangi Gram road from Ch 232m & 585m under Baliakandi upazila District Rajbari. Road ID No- 382075111 Estimate for Improvement of Shakura Mazar road 07-Mar-2021 08-Mar-2021 MSRDP/R/20-21/ Islampur UP from Ch. 00m-460m under Baliakandi 546111 LTM 2 17:00 12:30 BC/121 upazila District Rajbari. Road ID No-382074098. Improvement of Kashbamazail UP office- MSRDP/R/20-21/ Notabhanga Solua Iman Biswas house road Late 07-Mar-2021 08-Mar-2021 BC/122 Iman Biswas road by 25 mm Carpeting7mm seal 546113 LTM 3 17:00 12:30 coat from Ch.2600m-3165m under Pangsha upazila District Rajbari.Road ID No-382734191. -

Esdo Profile

` 2018 ESDO PROFILE Head Office Address: Eco Social Development Organization (ESDO) Collegepara (Gobindanagar), Thakurgaon-5100, Thakurgaon, Bangladesh Phone:+88-0561-52149, Fax: +88-0561-61599 Mobile: +88-01714-063360 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Dhaka Office : House # 37 ( Ground Floor), Road No : 13 PC Culture Housing Society, Shekhertak, Adabar, Dhaka-1207 Phone No :+88-02-58154857, Contact No : 01713149259 Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Abbreviation AAH - Advancing Adolescent Health ACL - Asset Creation Loan ADAB - Association of Development Agencies in Bangladesh ANC - Ante Natal Care ASEH - Advancing Sustainable Environmental Health AVCB Activating Village Courts in Bangladesh BBA - Bangladesh Bridge Authority BSS - Business Support Service BUET - Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology CAMPE - Campaign for Popular Education CAP - Community Action Plan CBMS - Community-Based Monitoring System CBO - Community Based organization CDF - Credit Development Forum CLEAN - Child Labour Elimination Action Network CLEAR - Child Labour Elimination Action for Real Change in urban slum areas of Rangpur City CLMS - Child Labour Monitoring System CRHCC - Comprehensive Reproductive Health Care Center CV - Community Volunteer CWAC - Community WASH Action Committee DAE - Directorate of Agricultural Engineering DC - Deputy Commissioner DMIE - Developing a Model of Inclusive Education DPE - Directorate of Primary Education DPHE - Department of Primary health Engineering -

Diversity of Cropping Patterns and Land Use Practices in Faridpur Region

Bangladesh Rice J. 21 (2) : 157-172, 2017 Diversity of Cropping Patterns and Land Use Practices in Faridpur Region A B M Mostafizur1*, M A U Zaman1, S M Shahidullah1 and M Nasim1 ABSTRACT The development of agriculture sector largely depends on the reliable and comprehensive statistics of the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity of a particular area, which will provide guideline to policy makers, researchers, extensionists and development workers. The study was conducted over all 29 upazilas of Faridpur region during 2015-16 using pre-tested semi-structured questionnaire with a view to document the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity of this area. From the present study it was observed that about 43.23% net cropped area (NCA) was covered by only jute based cropping patterns on the other hand deep water ecosystem occupied about 36.72% of the regional NCA. The most dominant cropping pattern Boro−Fallow− Fallow occupied about 24.40% of NCA with its distribution over 28 out of 29. The second largest area, 6.94% of NCA, was covered by Boro-B. Aman cropping pattern, which was spread out over 23 upazilas. In total 141 cropping patterns were identified under this investigation. The highest number of cropping patterns was identified 44 in Faridpur sadar and the lowest was 12 in Kashiani of Gopalganj and Pangsa of Rajbari. The lowest crop diversity index (CDI) was reported 0.448 in Kotalipara followed by 0.606 in Tungipara of Gopalganj. The highest value of CDI was observed 0.981 in Faridpur sadar followed by 0.977 in Madhukhali of Faridpur. -

Investigation of Animal Anthrax Outbreaks in the Human–Animal Interface at Risky Districts of Bangladesh During 2016–2017 SK Shaheenur Islam1, Shovon Chakma2, A

JOURNAL OF ADVANCED VETERINARY AND ANIMAL RESEARCH ISSN 2311-7710 (Electronic) http://doi.org/10.5455/javar.2018.e290 December 2018 A periodical of the Network for the Veterinarians of Bangladesh (BDvetNET) VOL 5, No. 4, PAGES 397–404 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Investigation of animal anthrax outbreaks in the human–animal interface at risky districts of Bangladesh during 2016–2017 SK Shaheenur Islam1, Shovon Chakma2, A. H. M. Taslima Akhter3, Nelima Ibrahim1, Faisol Talukder4, Golam Azam Chowdhuary5 1Department of Livestock Services, KrishiKhamar Sarak, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Emergency Center for Transboundary Animal Disease (ECTAD), Bangladesh 3FAO Food Safety Program, Food and Agriculture Organization, IPH Building, Dhaka, Bangladesh 4FETP, B fellow (3rd Cohort) Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR), Dhaka, Bangladesh 5Central Disease Investigation Laboratory (CDIL), Dhaka, Bangladesh ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Objective: The objective of the study was to explore the outbreak situation in terms of animal, Received May 26, 2018 place, and time towards minimizing the risk of animal infection at the source in future and subse- Revised September 05, 2018 quent spillover in human in the endemic rural settings. Accepted August 06, 2018 Methodology: An outbreak investigation team from the Department of Livestock Services visited Published December 02, 2018 in each of the outbreak sites to explore the event towards strengthening the control program in KEYWORDS the future. Meat samples of the infected slaughtered animals were collected to confirm the causal agent of the animal outbreak using polychrome methylene blue microscopic examination tech- Animal anthrax; Bangladesh; outbreak nique. Participatory epidemiology tool such as semi-structured interview had been used in these investigation investigations to realize the knowledge and practices of local people/cattle keepers on anthrax control and prevention in animal and human as well. -

Department of Sociology University of Dhaka Dhaka University Institutional Repository

THE NATURE AND EXTENT OF HOMICIDE IN BANGLADESH: A CONTENT ANALYSIS ON REPORTS OF MURDER IN DAILY NEWSPAPERS T. M. Abdullah-Al-Fuad June 2016 Department of Sociology University of Dhaka Dhaka University Institutional Repository THE NATURE AND EXTENT OF HOMICIDE IN BANGLADESH: A CONTENT ANALYSIS ON REPORTS OF MURDER IN DAILY NEWSPAPERS T. M. Abdullah-Al-Fuad Reg no. 111 Session: 2011-2012 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy June 2016 Department of Sociology University of Dhaka Dhaka University Institutional Repository DEDICATION To my parents and sister Dhaka University Institutional Repository Abstract As homicide is one of the most comparable and accurate indicators for measuring violence, the aim of this study is to improve understanding of criminal violence by providing a wealth of information about where homicide occurs and what is the current nature and trend, what are the socio-demographic characteristics of homicide offender and its victim, about who is most at risk, why they are at risk, what are the relationship between victim and offender and exactly how their lives are taken from them. Additionally, homicide patterns over time shed light on regional differences, especially when looking at long-term trends. The connection between violence, security and development, within the broader context of the rule of law, is an important factor to be considered. Since its impact goes beyond the loss of human life and can create a climate of fear and uncertainty, intentional homicide (and violent crime) is a threat to the population. Homicide data can therefore play an important role in monitoring security and justice. -

Flood in a Changing Climate: the Impact on Livelihood and How the Rural Poor Cope in Bangladesh

climate Article Flood in a Changing Climate: The Impact on Livelihood and How the Rural Poor Cope in Bangladesh Gulsan Ara Parvin *, Annya Chanda Shimi *, Rajib Shaw and Chaitee Biswas International Environmental and Disaster Management, Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan; [email protected] (R.S.); [email protected] (C.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (G.A.P.); [email protected] (A.C.S.) Academic Editor: Yang Zhang Received: 10 May 2016; Accepted: 1 December 2016; Published: 21 December 2016 Abstract: It is already documented that climate change will lead to an intensification of the global water cycle with a consequent increase in flood hazards. Bangladesh is also facing an increasing trend of flood disasters. Among the various risks and disasters in Bangladesh, flood is the most common and frequent. Floods make people vulnerable, as they take away their livelihoods at the first instance and leave them with little resources to overcome from the situation. Because of floods, rural poor communities face job loss, and two-thirds of their income is reduced, which limits their capabilities of preparedness, response, and recovery to subsequent floods. People cope with the situation by bearing substantial debts and a loss of productive assets. With an empirical field study in one of the most flood-prone upazilas (sub-districts) of Bangladesh, namely Goalanda Upazilla of the Rajbari district, this study intends to draw a “flood impact tree” of the study area. It also examines the impacts of flood on the livelihood of the rural poor and explores their coping strategies.