Nber Working Paper Series Recruit to Reject? Harvard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2003 Vol

The HARVARD FOUNDATION Newsletter FALL 2003 VOL. XXIII, NO. 1 Gov. Calderón of Puerto Rico Honored at Harvard Harvard Foundation Director Dr. S. Allen Counter presents Governor Sila M. Calderón with the Harvard Foundation Award. Sila M. Calderón, Governor of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico (center) and Antonio García-Padilla, President of the University of Puerto Rico (far left) are welcomed by Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers (right), and students, Barbara Sabot ‘07, Adiari Vazquez ‘05, Leyla Bravo ‘05, and Stephanie Paiz ‘05 (left to right). Distinguished WWII Veteran Airmen Honored at Harvard WWII Airmen John Leahr (left) and Herbert H. Heilbrun (right) honored at Winthrop House. Honorees John Leahr and Herbert H. Heilbrun welcomed by FAS Dean William C. The South Asian Association’s Kalpanam Dancers Kirby (center) and students Ellen Yiadom ‘06 (left), and Dina Maxwell ‘06 (right). performed at Lowell Hall. 2 HARVARD FOUNDATION NEWSLETTER, FALL 2003 3 | COVER STORY Sila M. Calderón, Governor of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is Honored with the Harvard Foundation Award COVER STORY | 6 Childhood Classmates John Leahr and Herbert H. Heilbrun, Once Pilots in Segregated U.S. Air Corps, Honored Together 10 | Annual Freshman Orientation Cultural Diversity Brunch Kuumba Singers | 12 Celebrate 33rd Annual Christmas Concert 13 | Raza’s Dia de los Muertos Celebration The First Annual | 14 Complexities of Color Writers Conference 16 | Harvard Black Alumni Weekend Draws 600 Students & Alums Martin Luther King Jr.’s | 18 Life Celebrated -

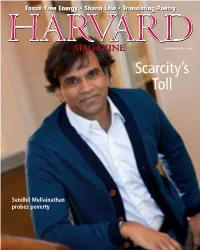

Scarcity's Toll

Fossil-Free Energy • Sharia Law • Translating Poetry May-June 2015 • $4.95 Scarcity’s Toll Sendhil Mullainathan probes poverty GO FURTHER THAN YOU EVER IMAGINED. INCREDIBLE PLACES. ENGAGING EXPERTS. UNFORGETTABLE TRIPS. Travel the world with National Geographic experts. From photography workshops to family trips, active adventures to classic train journeys, small-ship voyages to once-in-a-lifetime expeditions by private jet, our range of trips o ers something for everyone. Antarctica • Galápagos • Alaska • Italy • Japan • Cuba • Tanzania • Costa Rica • and many more! Call toll-free 1-888-966-8687 or visit nationalgeographicexpeditions.com/explore MAY-JUNE 2015 VOLUME 117, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 38 The Science of Scarcity | by Cara Feinberg Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan reinterprets the causes and effects of poverty 44 Vita: Thomas Nuttall | by John Nelson Brief life of a pioneering naturalist: 1786-1859 46 Altering Course | by Jonathan Shaw p. 46 Mara Prentiss on the science of American energy consumption now— and in a newly sustainable era 52 Line by Line | by Spencer Lenfield David Ferry’s poems and “renderings” of literary classics are mutually reinforcing JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 17 Biomedical informatics and the advent of precision medicine, adept algorithmist, when tobacco stocks were tossed, studying sharia, climate-change currents and other Harvard headlines, the “new” in House renewal, a former governor as Commencement speaker, the Undergraduate’s electronic tethers, basketball’s rollercoaster season, hockey highlights, -

Insider's Guide: Harvard Business School

presents mbaMission’s Insider’s Guide Harvard Business School Harvard University Boston, MA 2017–2018 mbaMission can help you stand apart from the thousands of other MBA applicants! Your Partner in the MBA Admissions Process Our dedicated, full-time admissions advisors work one-on-one with business school candidates, helping them showcase their most compelling attributes and craft the strongest possible applications. World’s Leading Admissions Consulting Firm With more five-star reviews on GMAT Club than any other firm, we are recommended exclusively by both leading GMAT prep companies, Manhattan Prep and Kaplan GMAT. Free 30-Minute Consultation Visit www.mbamission.com/consult to schedule your complimentary half-hour session and start getting answers to your most pressing MBA application and admissions questions! We look forward to being your partner throughout the application process and beyond. mbamission.com [email protected] THE ONLY MUST-READ BUSINESS SCHOOL WEBSITE Oering more articles, series and videos on MBA programs and business schools than any other media outlet in the world, Poets&Quants has established a reputation for well-reported and highly-creative stories on the things that matter most to graduate business education prospects, students and alumnus. MBA Admissions Consultant Directory Specialized Master’s Directory Poets&Quants’ MBA Admissions Consultant Directory For graduate business degree seekers looking for a offers future applicants the opportunity specialization along with or apart from an MBA, to find a coach or consultant to assist in their Poets&Quants' Specialized Master's Directory helps candidacy into a top business school. Search by cost, you narrow your results by program type, location, experience, education, language and more. -

HARVARD FOUNDATION Journal SPRING 2012 HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL

The HARVARD FOUNDATION Journal SPRING 2012 HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. XXXI, NO. 2 Portrait of Professor Martin Kilson Unveiled John Legend Honored as At Dudley House Harvard Foundation 2012 Artist of the Year Harvard Foundation Faculty Award Honoree: Professor David D. Potter The Harvard Foundation Honors University Marshal Jessica Matthews ‘10 and Julia Silverman ‘10 Jackie O’Neill Honored as the 2012 Scientists of the Year at the annual Harvard Foundation Science Conference In this issue: Human Rights Discussion Martin Luther King Jr. Birthday Celebration Actress Jada Pinkett Smith Harvard Tribute 2 HARVARD FOUNDATION JOURNAL, SPRING 2012 Table of Contents Harvard Foundation Journal Contents and Featured Programs p. 3 Letter from the Director p. 4-5 John Legend Honored at the 27th Cultural Rhythms Festival as 2012 Artist of the Year p. 6-7 Cultural Rhythms Festival Photos p. 8-9 Portrait Unveiling of Professor Martin Kilson, the first tenured African American professor at Harvard p. 10-11 Harvard Foundation Albert Einstein Science Conference Honors Soccket Ball Creators as Scientists of the Year p. 12-13 Kerry Kennedy Discusses the Importance of Human Rights at a luncheon at Winthrop House p. 13 The Portrait of Dr. Florence Ladd is Unveiled at Lowell House p. 14 Martin Luther King Jr. Birthday Celebration at Memorial Church p. 16-17 Harvard Foundation Student/Faculty Award Ceremony and Dinner at Mather House Student Initiated Programs p. 18-20 Harvard Foundation Student Grant Summary Reports p. 22 Sustained Dialogue Spring Update News & Notes p. 15 Race Relations Advisors Activity Reports p. 15 Monthly Student/Faculty Advisory Committee Meetings p. -

Calendar of Opening Days for New Students

Class of 2020 Calendar of Opening Days for New Students Freshman Dean’s Office fdo.fas.harvard.edu Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University OPENING DAYS CHECKLIST Required Attend Welcome to the Community on Tuesday, 8/23 Attend meetings with your entryway on Tuesday, 8/23, Wednesday, 8/24, and Thursday, 8/25 Learn about the curriculum at Liberal Education: A User’s Guide on Wednesday, 8/24 Join your Academic Adviser for lunch on Wednesday, 8/24 Learn about sexual assault prevention at Speak About It on Wednesday, 8/24 Learn about Harvard’s Honor Code on Thursday, 8/25 Participate in Conversations with Faculty on the Liberal Arts on Thursday, 8/25 Participate in Community Conversations on Tuesday, 8/30 Hear from President Drew Gilpin Faust and the Deans at Freshman Convocation and be in the photo of the Class of 2020 on Tuesday, 8/30 Complete Online Check-in by Tuesday, 8/30 at 11:59 pm Participate in Extended Orientation (check with your Proctor for dates and times) Get a physical examination (for intercollegiate athletes) on Friday, 9/2 Recommended Check online (placement-info.fas.harvard.edu) for placement exam times and locations, and complete any necessary exams Participate in all academic and advising events Take a Crimson Key tour of campus or Harvard Square Check out the schedule of student organization meetings and Late Night @ Harvard event listings Attend the faculty lecture given by Marcyliena Morgan on Thursday, 8/25 Check out Happy. Healthy. Harvard. on Thursday, 8/25 Apply for a Freshman Seminar -

N E W S L E T T

Harvard University Department of M usic MUSICnewsletter Vol. 14, No. 1 Winter 2014 Border Crossings: Kate van Orden Looks at 16th-Century Musical Migration Music Building When Professor Kate van Orden tracked a North Yard 16th-century French chansonnier across the Harvard University Alps to Italy, she discovered she’d embarked Cambridge, MA 02138 on a rich new vein of research. She’d also 617-495-2791 become the first Renaissance scholar to ask what it means when vernacular musics travel www.music.fas.harvard.edu beyond their natural, national contexts. “Western art music has always been INSIDE categorized: Lied is German; chanson, French; madrigal, Italian. But some genres 2 Abbate named University Professor cross borders. Following the migration of 2 Faculty News music and musicians disrupts the nationalist 3 Jason Robert Brown, A-I-R history of music in Europe.” Scholars of European music have long 3 Remembering Rulan Pian been working within the parameters of the Van Orden joined the Music Department faculty in July, 2013. She 19th century, says van Orden, which often 4 Czernowin’s Revolution also specializes in historical performance on the bassoon. sanitized history to give nations a false sense of wholeness, an ethnic purity. From this we have hard to write. In France, you feel the effect of the the myth of “folk,” who never traveled. Revolution, that two hundred plus years ago most “It’s just not true,” she explains. “People were of the books were thrown into piles and destroyed. really mobile in the 16th century. There were This didn’t happen in Italy. -

N E W S L E T T E R Vol

Harvard University Department of M usic MUSICn e w s l e t t e r Vol. 8, No. 1/Winter 2008 Revuluri on Empire and Modern Musical Thought Music Building North Yard in fin de siècle France Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 617-495-2791 www.music.fas.harvard.edu INSIDE INSIDE3 Faculty News 3 Ethiopian Conference in 2 April: Cultural Creativity 3 4 Graduate Student News 4 Photo: Library of Congress Professor Sindhu Revuluri joined the Harvard 5 Library News played out in music after the international influx faculty in 2007. She received her PhD in musi- 6 Ambrosiana at Harvard forefronted by World’s Fairs. cology from Princeton University, where she also Revuluri began studying 19th-century 7 Lachenmann Named taught for one year. Her research interests include World’s Fairs, particularly the 1889 and 1900 Fromm Professor exoticism and modernism in fin-de-siècle France, Expositions Universelles in Paris, as a way to contemporary Indian music and film, trends in 7 Bach Mozart to be released begin looking at how people heard musics from global pop music, and post-colonial approaches in April 2008 other places, and what they understood them to to music history. She is currently working on a be. The 1889 fair was the first where actual -mu 8 Save the date: Crosscurrents book about the relationship between empire and sicians--African, Middle Eastern, and southeast Conference, Oct. 2008 modernist musical thought in France. Asian—were brought to France to perform. “They 8 Alumnae News Four years ago Sindhu Revuluri was conducting built housing structures, based on the style of 9 Mekonnen’s African Roots research in France when a highly charged debate homes in Asia, or the Middle East, for example, 9 Inside Beethoven erupted about whether or not young Muslim girls and imported people to live in them for the six 10 Kraft’s Film Music 101 should be allowed to wear veils in school. -

2021 Massachusetts History Conference History: a Massachusetts Community Activity

2021 Massachusetts History Conference History: A Massachusetts Community Activity Presented by Massachusetts History Alliance With the generous support of our sponsors: Mass Humanities, Premier Conference Partner MA State Historical Records Advisory Board, Conference Partner University of Massachusetts Amherst Public History Program | Dorchester Historical Society University of Massachusetts Boston Graduate Studies in Public History & Archives and Joseph P. Healey Library Supporting Associates Robert Forrant | Mike Potaski Associates Digital Commonwealth | House of the Seven Gables | Essex National Heritage Commission Old Colony History Museum | Worcester Historical Museum Friends Museum & Collector Resource | Swift River Press: Public History & Communications by Pleun Bouricius William G. Pomeroy Foundation | Roche Brothers Contributors Tsongas Industrial History Center | Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) Metropolitan Waterworks Museum Monday, June 7th, 11:00 – 6:00 Time Session 11:00 – 6:00 Mass History Commons Exhibitor Hall 11:00 – 6:00 Café on the Commons 11:00 - 12:00 Community-Driven Exhibit Planning Researching and Reckoning with Massachusetts' Complicity in and Resistance to 11:00 - 12:00 Slavery Supporting and Sustaining Volunteers: From archival projects to institutional 11:00 - 12:00 programming 12:15 - 1:00 Coffee Hour 1:00 - 1:15 Welcome 1:15 - 2:15 Keynote Address: Dr. Diana Sierra Becerra 2:30 - 3:30 Finding Community through History 2:30 - 3:30 Curating Marginalized Heritage Engaging Community, Building Digital -

Agassiz Neighborhood Study Report and Addendum 2003

■ ■ ■ ■ A G A S S I Z N E I G H B O R H O O D S T U D Y A JOINT REPORT OF THE AGASSIZ NEIGHBORHOOD STUDY COMMITTEE AND THE CAMBRIDGE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT ■ ■ ■ ■ A G A S S I Z N E I G H B O R H O O D S T U D Y Cambridge City Manager Robert W. Healy Deputy City Manager Richard C. Rossi Cambridge City Council Councillor Michael A. Sullivan, Mayor Councillor Henrietta Davis, Vice Mayor Councillor Marjorie C. Decker Councillor Anthony D. Galluccio Councillor David P. Maher Councillor Brian Murphy Councillor Kenneth E. Reeves Councillor E. Denise Simmons Councillor Timothy J. Toomey, Jr. Cambridge Planning Board Thomas Anninger, Chair Barbara Shaw, Vice Chair Larissa Brown Kevin Benjamin, Associate Member Florrie Darwin Hugh Russell William Tibbs Pamela Winters Published, April 2003 Credits Agassiz Neighborhood Study Committee Amy Barad, Eustis Street Joel Bard, Wendell Street Deborah Galef, Hammond Street Miriam Goldberg, Frost Street Ross Hoffman, Wendell Street Fred Meyer, Hammond Street Dave Wood, Gorham Street Community Development Department Project Staff Stuart Dash, Director of Community Planning Rebecca Sozanski, Neighborhood Planner, Project Manager Taha Jennings, Neighborhood Planner Clifford Cook, Planning Information Manager Robin Shore, Graphics Director Venita Mathias, Former Neighborhood Planner Additional Participating Staff Beth Rubenstein, Assistant City Manager for Community Development Susan Glazer, Deputy Director for Community Development Lester Barber, Land Use and Zoning Director Roger Boothe, Urban Design Director Darcy Jameson, Housing Director Susanne Rasmussen, Environmental and Transportation Planning Director Estella Johnson, Economic Development Director Charles Sullivan, Executive Director of the Cambridge Historical Commission The Agassiz Neighborhood Study Committee and the Community Development Department would like to thank all the Agassiz resi dents who participated in the public forums and committee meetings. -

John H. Finley, Jr., 91, Classicist at Harvard for 43 Years, Is Dead

Figure F1 “John Harvard, Founder, 1638” Bronze statue, 1884, by Daniel Chester French of John Harvard (1607–1638), an English minister who on his deathbed made a bequest of his library and half of his estate to the “schoale or Colledge recently undertaken” by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The grateful recipients named the college in his honor. “He gazes for a moment into the future, so dim, so uncertain, yet so full of promise, promise which has been more than realized.” Photo (April 27, 2008) reprinted courtesy of Alain Edouard Source: https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Harvard_statue.jpg Figure F2 University Hall on an early spring evening Reprinted courtesy of Harvard University Harvard College Class of 1957 RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS 60th REUNION COMMITTEE Co-Chairs James L. Joslin John A. Simourian Wallace E. Sisson Members Philip J. Andrews Harvey J. Grasfield Evan Randolph IV Philip J. Arena Peter Gunness Edward J. Rolde Hugh Blair-Smith Alan Harwood George Sadowsky Jeremiah J. Bresnahan Philip C. Haughey David W. Scudder Victor R. Brogna Arthur C. Hodges A. Richard Shain Geoffrey T. Chalmers Newton E. Hyslop, Jr. John A. Simourian Thomas F. Crowley Lawrence A. Joseph Wallace E. Sisson Christopher Crowley James L. Joslin Charles Steedman Alexander Daley Michael D. Kline Robert J. Swartz Peter F. Davis Bruce Macdonald J. Owen Todd John E. Dowling Anthony M. Markella Thomas H. Townsend S. Warren Farrell Neil P. Olken Thomas H. Walsh, Jr. J. Stephen Friedlaender Carl D. Packer Ronald M. Weintraub Evan M. Geilich John Thomas Penniston Philip M. Williams Martin S. -

ANTHONY ABRAHAM JACK 6 Appian Way Cambridge, MA 02138 Anthony [email protected]

ANTHONY ABRAHAM JACK 6 Appian Way www.anthonyabrahamjack.com Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2018 – Assistant Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Harvard University 2018 – Shutzer Assistant Professor, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University Spring 2020 James Patterson Fellow, Vanderbilt University 2017 – Faculty Fellow, Pforzheimer House, Harvard University 2016 – 2020 Junior Fellow, Harvard Society of Fellows, Harvard University EDUCATION Harvard University 2016 Ph.D., Sociology 2011 A.M., Sociology Amherst College 2007 B.A., Women’s and Gender Studies; Religion cum laude, Moseley Prize in Religion, Obed Finch Slingerland Memorial Prize, John Sumner Runnells Memorial Award for Scholarship and Citizenship HONORARY DEGREES 2020 Muhlenberg College RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTERESTS Culture, Education, Race/Ethnicity, Children and Youth, Poverty, Inequality, Qualitative Methods PUBLISHED WORKS (*denotes equal authorship) (graduate student coauthor in italics) Jack, Anthony Abraham. 2019. The Privileged Poor: How Elite Colleges Are Failing Disadvantaged Students. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. § 2020 Outstanding Book Award, Social Problems Theory Division, Society for the Study of Social Problems § 2020 Mirra Komarovsky Book Award, Eastern Sociological Society § 2020 Pierre Bourdieu Best Book Award, Honorable Mention, Sociology of Education Section, American Sociological Association § 2020 PROSE Award Finalist, Education Practice, Association of American Publishers -

Historymusicdepartment1 1

THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC 1991 TO 2011 Compiled and Edited by Lesley Bannatyne 2015 John Knowles Paine Concert Hall. Photo by Shannon Cannavino. Cover photos by Kris Snibbe [Harvard News Office], HMFH Architects, Inc., Harvard College Libraries, Rose Lincoln [Harvard News Office] THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC 1991 TO 2011 Compiled and Edited by Lesley Bannatyne Department of Music Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 2015 Photographs in this volume were provided by the Department of Music unless otherwise noted. Articles are reprinted from the Department’s newsletters, Harvard Crimson and Harvard Gazette. © 2015 President and Fellows of Harvard University 2nd printing January 2017 All rights reserved. CONTENTS Preface vii Chapter One: The Chairs 1 Chapter Two: Undergraduate Studies 11 Chapter Three: Graduate Studies 23 Chapter Four: Musicology 33 Chapter Five: Ethnomusicology 51 Chapter Six: Theory 67 Chapter Seven: Composition 77 Chapter Eight: Performance 97 Chapter Nine: Conferences, Symposia, Colloquia, Lectures 111 Chapter Ten: Concert Highlights 119 Chapter Eleven: Eda Kuhn Loeb Music Library 127 Chapter Twelve: The Building 143 Appendices 151 Index 307 Music Department, 1992 Music Department picnic, late 1990s Appendices i. Music Department Faculty 151 ii. Biographical Sketches of Senior Professors, Lecturers & Preceptors 165 iii. Donors 175 iv. Teaching Fellows 179 v. Curriculum 183 vi. Fromm Commissions 207 vii. Recipients of the PhD degree 211 viii. Faculty Positions Held by Former Graduate Students 217 ix. Recipients of Department Awards and Fellowships 221 x Recipients of the AB degree and Honors Theses 227 xi. Visiting Committees 239 xii. Conferences, Colloquia, Symposia, Lectures 241 xiii. Concerts and Special Events 255 xiv.