Art Therapy in a Museum Setting and Its Potential at the Rubin Musuem of Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

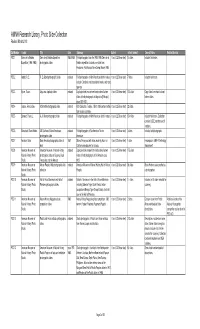

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013 Call Number Creator Title Date Summary Extent Extent (format) General Notes Related Archival PSC 1 Cerro de la Neblina Cerro de la Neblina Expedition 1984-1989 Field photographs from the 1984-1985 Cerro de la 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 14 slides Includes field notes. Expedition (1984-1985) photographic slides Neblina expedition. Includes one slide from Amazonas, Rio Mavaca Base Camp, March 1989. PSC 2 Abbott, R. E. R. E. Abbott photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature, 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 7 slides Includes field notes. includes Cardinals, red-shouldered hawks, and song sparrow. PSC 3 Byron, Oscar. Abyssinia duplicate slides undated Duplicate slides made from hand-colored lantern 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 100 slides Copy slides from hand colored slides of field photographs in Abyssinia [Ethiopia] lantern slides. circa 1920-1921. PSC 4 Jaques, Francis Lee. ACA textile photographic slides undated ACA Collection. Textiles, 15th to 18th century textiles 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 22 slides from various countries. PSC 5 Bierwert, Thane L. A. A. Allen photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature. 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 154 slides Includes field notes. Collection contains USDE numbers and K numbers. PSC 6 Blanchard, Dean Hobbs. AG Southwest Native Americans undated Field photographs of Southwestern Native 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 3 slides Includes field photographs. photographic slides Americans PSC 7 Amadon, Dean Dean Amadon photographic slides of 1957 Slide of fence post with holes made by Acorn or 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 1 slide Fence post in AMNH Ornithology birds California woodpecker for storage. -

Tibetans in the New York Metro Area QUICK FACTS: ALL PEOPLES INITIATI VE LAST UPDATED: 11/2009

Tibetans in the New York Metro Area QUICK FACTS: ALL PEOPLES INITIATI VE LAST UPDATED: 11/2009 Place of Origin: Sonam Tashi, a Tibetan man whose father was killed by Chinese border patrol when he Tibet (China) via India was three years old, comes on March 10th of every year to a plaza by the UN building, ral- (mainly Dharamsala) lying on behalf of a free Tibet. He solemnly claims, “Every people need a freedom [....] Lot and Nepal of people in China are not free.” It has been about fifty years since the Chinese occupied Tibet, and the sting is still felt by the estimated three thousand Tibetans who now live in Significant Subgroups: the New York Metro area.1 On the March 10th National Tibetan Uprising Day, hundreds of Tibetans often organize along the four main Tibetans and sympathizers march to the UN and Chinese Consulate, shouting such cries schools of Tibetan Bud- as, “China lie, people die,” and, “China out of Tibet now.” While New York is where they dhism (Gelugpas, live, it is certainly not their home. Nyingmas, Sakyas, and Kagyus)2 When Did They Come to New York? Location in Metro New For centuries, Tibet was an isolated country. Very few came York: Queens (Jackson in. Very few went out. All of that changed in 1949 when the Heights, Astoria); Chinese took control of Tibet—an act that led tens of thou- Brooklyn (Crown sands of Tibetans to resettle in India and Nepal. The Tibet- Heights); Manhattan ans’ struggle for their homeland has continued ever since. -

Off* for Visitors

Welcome to The best brands, the biggest selection, plus 1O% off* for visitors. Stop by Macy’s Herald Square and ask for your Macy’s Visitor Savings Pass*, good for 10% off* thousands of items throughout the store! Plus, we now ship to over 100 countries around the world, so you can enjoy international shipping online. For details, log on to macys.com/international Macy’s Herald Square Visitor Center, Lower Level (212) 494-3827 *Restrictions apply. Valid I.D. required. Details in store. NYC Official Visitor Guide A Letter from the Mayor Dear Friends: As temperatures dip, autumn turns the City’s abundant foliage to brilliant colors, providing a beautiful backdrop to the five boroughs. Neighborhoods like Fort Greene in Brooklyn, Snug Harbor on Staten Island, Long Island City in Queens and Arthur Avenue in the Bronx are rich in the cultural diversity for which the City is famous. Enjoy strolling through these communities as well as among the more than 700 acres of new parkland added in the past decade. Fall also means it is time for favorite holidays. Every October, NYC streets come alive with ghosts, goblins and revelry along Sixth Avenue during Manhattan’s Village Halloween Parade. The pomp and pageantry of Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in November make for a high-energy holiday spectacle. And in early December, Rockefeller Center’s signature tree lights up and beckons to the area’s shoppers and ice-skaters. The season also offers plenty of relaxing options for anyone seeking a break from the holiday hustle and bustle. -

Ann Shafel Special Talk

12 བོད་ཁང་། Tibet House Cultural Centre of His Holiness the Dalai Lama Organizes A Lecture on "Science and the Sacred: the Preservation of Sacred Art" By Ms. Ann Shaftel & Dr. Robert J. Koestler Ann Shaftel Ann Shaftel serves as a Preservation Consultant for international clients. Ann has the highest international credentials in this field: Fellow of the International Institute of Conservation, Fellow of American Institute for Conservation, a member of Canadian Association of Professional Conservators. She holds an MS degree in Art Conservation, and MA degree in Asian Art History. Ann’s clients include governments, museums, archives, universities, and Buddhist monasteries worldwide, including the Art Institute of Chicago, American Museum of Natural History, Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, The Field Museum, Rubin Museum of Art, Yale University, University of Michigan Museum, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art, Royal Ontario Museum, National Gallery of Victoria, University of Melbourne, Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Mindrolling Monastery and other monasteries and nunneries. Ann teaches training sessions on The Care of Sacred Art in North America, Europe, Australia, India, Bhutan, and China. Ann is active in Preservation Outreach, on TV, radio, online and in print. She has written and published many scholarly and practical articles, including in the Journal of Art Theft. Robert J. Koestler has been director of the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute (MCI) since August 2004. He has a 40 years of museum experience include nearly 24 years at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and eight years at the American Museum of Natural History. -

Delivering Service and Support

THE TIBET FUND YEARS SPECIAL REPORT HIS HOLINESS THE 14TH DALAI LAMA 1 SIKYONG Dr. LOBSANG SANGAY Senator Dianne Feinstein 2 3 Program (KAP) was initiated to address and nunneries as well as cultural None of our work would have been the unmet medical, educational, and institutions such as the Tibetan possible without the support of our economic needs of Tibetans in Tibet. Institute for Performing Arts, Library partners, individual donors, grants PRESIDENT With funding from private donors, TTF for Tibetan Works and Archives, and from foundations, and major funding RINCHEN DHARLO built Chushul Orphanage and funded Nepal Lhamo Association. from the US Department of State’s two other children’s homes. TTF also Bureau of Population, Refugees and funded the construction of Lhasa Eye In 1997, we initiated the Blue Book Migration and Bureau of Education Center and sponsored several surgical Project, which is seen as an effective and Cultural Affairs, The Office of eyes camps restoring more than 2,000 way for individuals to support the Citizen Exchanges of the Bureau of sights. KAP at that time has won the Tibetan people. From 1997 to 2015, Educational and Cultural Affairs, support and confidence of Tibetan TTF has raised a total of over $310,000 and the USAID. We would like to authorities at the highest levels both in from individual donors and transferred express our deepest gratitude to the perSOnal Tibet and in exile and has successfully that fund to the Central Tibetan US Congress and Administration, reflections provided resources and training for Administration. Establishment of the whose continued support and belief education and health projects in Tibet Tibetan Sponsorship Program in 1999 in our mission has provided critical as well as in mainland China and study has also been very satisfying. -

Asia Society Launches Asia Week in New York With

News Public Relations Department 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021-5088 www.AsiaSociety.org Phone 212.327.9271 Contact: Elaine Merguerian, 212-327-9271 Fax 212.517.8315 [email protected] E-mail [email protected] MUSEUMS, GALLERIES AND AUCTION HOUSES ANNOUNCE SCHEDULE OF EVENTS DURING ASIA WEEK NEW YORK, MARCH 20–28, 2010 Newly created AsiaWeekNewYork.org website launches New York, March 1, 2010—Asia Society is pleased to announce the detailed schedule for Asia Week New York, from March 20–28, 2010, which includes activities of over 40 of New York's major museums, art galleries and auction houses. As the city's largest and most diverse series of cultural events focusing on Asian art, the initiative—coordinated by Asia Society—builds on a decade-long history of New York dealers staging shows and auction houses conducting sales during spring Asia Week. This year represents the first time that a single institution has coordinated a city-wide effort among museums, auction houses, galleries and dealers. Details of the events, most of which are free and open to the public, are listed on the newly launched Asia Week New York website, www.AsiaWeekNewYork.org. Programming during the week will encompass public lectures, panel discussions, and museum and gallery exhibitions and receptions that promote understanding and appreciation of Asian art. The endeavor aims to look at new developments and trends in Asian art from multiple perspectives and at the broad range of traditional Asian arts being presented during March. “Asia Week brings together every major New York institution that has a significant interest in Asian art, organizing and formalizing the myriad activities relating to Asian art that occur each spring,” says Asia Society Museum Director Melissa Chiu. -

Special Topic Paper: Tibet 2008-2009

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Special Topic Paper: Tibet 2008-2009 October 22, 2009 This Commission topic paper adds to and further develops information and analysis provided in Section V—Tibet of the Commission’s 2009 Annual Report, and incorporates the information and analysis contained therein. Congressional-Executive Commission on China Senator Byron L. Dorgan, Chairman Representative Sander M. Levin, Cochairman 243 Ford House Office Building | Washington, DC 20515 | 202-226-3766 | 202-226-3804 (FAX) www.cecc.gov Congressional-Executive Commission on China Special Topic Paper: Tibet 2008-2009 Table of Contents Findings ........................................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction: Tibetans Persist With Protest, Government Strengthens Unpopular Policies ...............................3 Government Shifts Toward More Aggressive International Policy on Tibet Issue ...............................................5 Beijing Think Tank Finds Chinese Government Policy Principally Responsible for the “3.14 Incident” ...................................................8 Status of Negotiations Between the Chinese Government and the Dalai Lama or His Representatives............13 The China-Dalai Lama Dialogue Stalls ..............................................................................................................................................................14 The Eighth Round of Dialogue, Handing Over -

Holy Cross Fax: Worcester, MA 01610-2395 UNITED STATES

NEH Application Cover Sheet Summer Seminars and Institutes PROJECT DIRECTOR Mr. Todd Thornton Lewis E-mail:[email protected] Professor of World Religions Phone(W): 508-793-3436 Box 139-A 425 Smith Hall Phone(H): College of the Holy Cross Fax: Worcester, MA 01610-2395 UNITED STATES Field of Expertise: Religion: Nonwestern Religion INSTITUTION College of the Holy Cross Worcester, MA UNITED STATES APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Literatures, Religions, and Arts of the Himalayan Region Grant Period: From 10/2014 to 12/2015 Field of Project: Religion: Nonwestern Religion Description of Project: The Institute will be centered on the Himalayan region (Nepal, Kashmir, Tibet) and focus on the religions and cultures there that have been especially important in Asian history. Basic Hinduism and Buddhism will be reviewed and explored as found in the region, as will shamanism, the impact of Christianity and Islam. Major cultural expressions in art history, music, and literature will be featured, especially those showing important connections between South Asian and Chinese civilizations. Emerging literatures from Tibet and Nepal will be covered by noted authors. This inter-disciplinary Institute will end with a survey of the modern ecological and political problems facing the peoples of the region. Institute workshops will survey K-12 classroom resources; all teachers will develop their own curriculum plans and learn web page design. These resources, along with scholar presentations, will be published on the web and made available for teachers worldwide. BUDGET Outright Request $199,380.00 Cost Sharing Matching Request Total Budget $199,380.00 Total NEH $199,380.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Ms. -

Maxine Henryson Resume

A.I.R. MAXINE HENRYSON RESUME 478 West Broadway #3N New York, NY 10012 www.maxinehenryson.com 917 656 8610 [email protected] EDUCATION 1986 M.F.A. Photography, University of Illinois, IL 1973 M.A.T. Sculpture, University of Chicago, IL 1970 M.A. Phil. Sociology, University of London, ENG 1965 B.S. Sociology, Simmons College, Boston, MA SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2014 Calculated Coincidence, Kleinschmidt Fine Photographs, Weisbaden, Germany 2014 from Ujjayi’s Journey, A.I.R. Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Ujjayi’s Journey, ARC Gallery, Chicago, IL 2007 Time Dissolutions, Sometimes Collective, Barney’s New York, NY 2006 Selections from I-Dea the Goddess Within, Mary Goldman Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2005 X is Y and is Z, Russia, The Shala, New York, NY 1998 X is Y and is Z, Russia Stroganoff Palace of The Russian Museum, St Petersburg, Russia Dressed In White,” The Ramapo Curatorial Prize Exhibition, Ramapo College, NJ 1997 I-Dea the Goddess Within, Linda Kirkland Gallery, New York, NY 1996 Selections from I-Dea the Goddess Within, Bernard Toale Gallery, Boston, MA 1995 I-Dea the Goddess Within, Usdan Gallery, Bennington College, VT 1991 American Rites, ARC Gallery, Chicago, IL 1987 Reflections, 22 Wooster Gallery, New York, NY Reflections, Artemisa Gallery, Chicago, IL SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2015 Tendrel, Tibet House, New York, NY 2014 You are my Dear Blossoms, Standing In Love, A.I.R. Gallery, Brooklyn, NY Nation II, Sideshow Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2013 Generation X the Red/Pink Show, A.I.R. Gallery, Brooklyn, NY Illuminators, O.K. Harris, New York, NY Otherwise: Queer Scholarship into Song, Dixon Place, NY 40/40, A.I.R. -

Tommemorative Journal

Concierge Choice Awards Commemorative Journal COMMEMORATIVE JOURNAL 2010-2011 CONCIERGECHOICEAWARDS.COM NYC’s origiN AL CITY GUIDE SINCE 1982 C I TYG U I D E NY.CO M Honors the New York City Association of Hotel Concierges for creating the Concierge Choice Awards. Congratulations to all the winners and nominees City Guide Magazine, a Davler Media Group publication, is the largest circulation visitor magazine in New York City. 1440 Broadway, Fifth Floor, New York, NY 10018 | 212.315.0800 | www.cityguideny.com 2010 NYCAHC EXecUTIVE BOARD Domenic Alfonzetti • President Frank Albrezzi • Vice President Francisco Andeliz • Secretary Beatriz McGowan • Treasurer Loida Diaz • Public Relations Roxie McCovins • Membership James Lamboglia • Social Coordinator A heartfelt welcome to all the nominees, friends and professional partners to the Fourth Annual Concierge Choice Awards. As the president of the New York City Association of Hotel Concierges, which represents so many individuals dedicated to excellence in service, I know that we are motivated by a genuine desire to serve and are committed to providing the best possible service to our visitors throughout their stay. You, the nominees, have been chosen by our Concierge community as the best of the best. Thank you for your dedication in creating and making our guest experiences memorable. We value your partnership. Together, we will surpass our guests’ expectations. Working together, we can collectively bring new and repeat business to the “Capital of the World,” New York City, increasing the total number of visitors from 45.5 to over 50 million. Congratulations to the winners and nominees. You have earned the recognition. -

Annual Report 2016 36 Years of Service to the Tibetan Community

The Tibet Fund Annual Report 2016 36 Years of Service to the Tibetan Community “Since its establishment in 1981, The Tibet Fund has contributed to the building and development of a robust Tibetan community in exile. It has also supported Tibetans in Tibet in socio-economic areas. Over three and a half decades, it has assisted the Tibetan leadership in exile in its work on infrastructural development, refugee rehabilitation, and cultural preservation, while also backing education, healthcare and other capacity-building programs. Through such support, we have been able to strengthen our cultural institutions and undertake projects essential for the preservation of the Tibetan cultural heritage that is the very core of our civilization.” — HIS HOLINESS THE 14TH DALAI LAMA, HONORARY PATRON, THE TIBET FUND The Tibet Fund’s mission is to preserve the distinct cultural identity of the Tibetan people. Founded in 1981 under the patronage of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, The Tibet Fund is the leading nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting and strengthening Tibetan communities, both in exile and inside Tibet. Each year, The Tibet Fund reaches out to almost entire Tibetan refugee community in exile through programs for health, education, refugee rehabilitation, cultural preservation, elder care, and community development. Health programs have contributed to substantial reductions in infant and child mortality rates, morbidity, and tuberculosis incidence. Education initiatives have raised literacy rates, provided schooling for thousands of children, equipped adult refugees with new livelihood skills, and provided scholarships for over 444 Tibetans to pursue higher studies in the US and many more to attend universities in India and Nepal. -

Tibet Chic: Myth, Marketing, Spirituality and Politics in Musical

“TIBET CHIC”: MYTH, MARKETING, SPIRITUALITY AND POLITICS IN MUSICAL REPRESENTATIONS OF TIBET IN THE UNITED STATES by Darinda J. Congdon BM, Baylor, 1997 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Darinda Congdon It was defended on April 18, 2007 and approved by Dr. Nicole Constable Dr. Evelyn S. Rawski Dr. Deane L. Root Dr. Andrew N. Weintraub Dr. Bell Yung Dissertation Director ii Copyright © by Darinda Congdon 2007 iii “TIBET CHIC”: MYTH, MARKETING, SPIRITUALITY AND POLITICS IN MUSICAL REPRESENTATIONS OF TIBET IN THE UNITED STATES Darinda Congdon, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 This dissertation demonstrates that Tibetan music in the United States is directly related to multiple Western representations of Tibet in the United States, perpetuated from the 1800s to the present, and that these representations are actively utilized to market Tibetan music. These representations have also impacted the types of sounds most often used to musically represent Tibet in the United States in unexpected ways. This study begins with the question, “What is Tibetan music in the United States?” It then examines Tibetan music in the United States from a historical, political, spiritual and economic perspective to answer that question. As part of this investigation, historical sources, marketing sources, New Age religion, the New York Times, and over one hundred recordings are examined. This work also applies marketing theory to demonstrate that “Tibet” has become a term in American culture that acts as a brand and is used to sell music and other products.