Paul Klee, His Life and Work in Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feininger Klee Bauhaus Feininger Klee Bauhaus

feininger klee bauhaus feininger klee bauhaus 01.05.2019 — 18.01.2020 New York Dortmund Wien Inhalt contents 06 Lyonel Feininger – vom Karikaturisten zum Bauhausmeister Wolfgang Büche 07 Lyonel Feininger —from Caricaturist to Bauhaus Master Wolfgang Büche 22 werke Lyonel Feininger 22 works by Lyonel Feininger 60 lyonel feininger über paul klee 61 lyonel feininger on paul klee 70 werke Paul Klee 70 works by paul klee 84 biografien 84 biographies 92 ausgestellte werke 92 exhibited works 104 impressum Die Bauhausmeister auf dem Dach des Bauhauses in Dessau anlässlich der Eröffnung am 4. und 5. Dezember 1926 The Bauhaus Masters on the roof of the Bauhaus in Dessau at its opening on December 4 & 5, 1926 104 imprint Lyonel Feininger 04 05 Lyonel Feininger Lyonel Feininger – vom Karikaturisten —from Caricaturist zum Bauhausmeister to Bauhaus Master Wolfgang Büche Wolfgang Büche Als Lyonel Feininger im Mai 1919 als der erstberufene Bau- When Lyonel Feininger was sitting on the train to Weimar hausmeister im Zug nach Weimar saß, gehörte er in Deutsch- in May 1919 on his way to become one of the first Bauhaus land bereits zu den arrivierten Malern. Es gab Sammler masters appointed to teach at the school, he was already seiner Werke und Museen begannen sich für sein Schaffen a well-established painter in Germany. There were already zu interessieren. Mit seiner ersten Einzelausstellung 1917 in a few collectors of his work, and museums were starting to der Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin war er endgültig als einer der take an interest in him. His first solo exhibition at the Galerie Protagonisten der Moderne in Deutschland eingeführt. -

Final Report Provenance Research

Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation Final Report Project management Dr. Thorsten Sadowsky, Director Annick Haldemann, Registrar [email protected] Project handling and report Julia Sophie Syperreck MA, Research Assistant [email protected] 31 August 2018 Kirchner Museum Davos Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation 2 Contents 3 I. Work report 4 a. The situation and state of research at the beginning of the project 5 b. Work performed by the project staff and project schedule 6 c. Methodical approach and manner of publication of the findings 7 d. Object statistics 9 e. List of the historical agents (individuals and institutions) relevant to the project 10 f. Documentation of the findings for third parties 11 II. Summary 12 a. Evaluation of the findings 12 b. Unresolved issues and need for further research 13 III. Appendix: List of works Kirchner Museum Davos I. Work report Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation 4 a. The situation and state of research at the beginning of the project At the beginning of the project an assessment was made which groups of works within the collection are more likely to be linked to the “liquidation” of private and public collections during the Nazi dictatorship in Germany in the years from 1933 to 1945. It was found that there is only very patchy provenance information for the forty-two artworks donated in 2000 to the Kirchner Museum Davos by “Rosemarie and Konrad Baumgart-Möller in memory of Ferdinand Möller, Berlin.” Since “Möller” is one of the red-flag names in provenance research, the investigation of this part of the collection was given priority. -

Die Brücke Der Blaue Reiter Expressionists

THE SAVAGES OF GERMANY DIE BRÜCKE DER BLAUE REITER EXPRESSIONISTS 22.09.2017– 14.01.2018 The exhibition The Savages of Germany. Die Brücke and Der DIE BRÜCKE (“The Bridge” in English) was a German artistic group founded in Blaue Reiter Expressionists offers a unique chance to view the most outstanding works of art of two pivotal art groups of 1905 in Dresden. The artists of Die Brücke abandoned visual impressions and the early 20th century. Through the oeuvre of Ernst Ludwig idyllic subject matter (typical of impressionism), wishing to describe the human Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and others, the exhibition inner world, full of controversies, fears and hopes. Colours in their paintings tend focuses on the innovations introduced to the art scene by to be contrastive and intense, the shapes deformed, and the details enlarged. expressionists. Expressionists dedicated themselves to the Besides the various scenes of city life, another common theme in Die Brücke’s study of major universal themes, such as the relationship between man and the universe, via various deeply personal oeuvre was scenery: when travelling through the countryside, the artists saw an artistic means. opportunity to depict man’s emotional states through nature. The group disbanded In addition to showing the works of the main authors of German expressionism, the exhibition attempts to shed light in 1913. on expressionism as an influential artistic movement of the early 20th century which left its imprint on the Estonian art DER BLAUE REITER (“The Blue Rider” in English) was another expressionist of the post-World War I era. -

Jewish Fates: Richard Fuchs and Karl Wolfskehl

Jewish Fates: Richard Fuchs and Karl Wolfskehl By Friedrich Voit After three years of providing a varied programme of theatre, opera, concerts and lectures the Jüdische Kulturbund in Deutschland (Jewish cultural League in Germany) invited the leaders of its branches to a national conference in Berlin for stocktaking and planning of the future direction of the League. The Kulturbund was founded in 1933, a few months after the Nazi regime had come to power which began to purge the theatres, orchestras and other cultural institution from their „non-Arian‟ Jewish members. Almost overnight hundreds of Jewish actors, singers, musicians etc. found themselves without employment. Two of them having been dismissed from their positions at the operatic stages in Berlin, the production assistant Kurt Baumann and the conductor Kurt Singer, proposed a new organisation serving the Jewish community in Berlin and other major cities where most of the Jewish minority lived. They realized that the roughly 175.000 Jews, most of them well educated and with an active interest in the arts, would provide a big enough audience to support their own cultural institutions (theatre, opera, and orchestras). More importantly they also gained the support of the Nazi authorities, especially of Hans Hinkel, the newly appointed head of the Prussian Theatre commission. Such an institution suited the Nazis for several reasons: The regime would be able to exploit the organization in international propaganda by citing it as evidence that Jews were not being mistreated; it could -

Paul Klee Centennial: Prints and Transfer Drawings

Paul Klee Centennial PRINTS AND TRANSFER PR AWTM1S jk f i-Vioo JJBRARYJ ' Museumcf !,; &:n : Rail h lee Centennial PRINTS AND TRANSFER DRAWINGS January8 - April3, 1979 TheMuseum of ModernArt, New York /hclui/C tit? ft i j iSj T> Trusteesof The Museumof ModernArt WilliamS. Paley,Chairman of the Board;Gardner Cowles, Mrs.Bliss Parkinson, David Rockefeller, ViceChairmen; Mrs. John D. Rockefeller3rd, President;Mrs. Frank Y. Larkin,Donald B. Marron, JohnParkinson III, Vice Presidents; John ParkinsonIII, Treasurer; Mrs. L. vA.Auchincloss, EdwardLarrabee Barnes, Alfred H. Barr,Jr.,* Mrs.Armand P. Bartos,Gordon Bunshaft, Shirley C. Burden,William A.M. Burden, Thomas S. Carroll, FrankT. Cary, IvanChermayeff, Mrs. C. Douglas Dillon,Gianluigi Gabetti, PaulGottlieb, George HeardHamilton, Wallace K. Harrison,*Mrs. Walter Hochschild,*Mrs. John R. Jakobson,Philip Johnson, Mrs.Frank Y. Larkin,Ronald S. Lauder,John L. Loeb, RanaldH. Macdonald,*Mrs. G. Macculloch Miller,*J. IrwinMiller,* S. I. Newhouse,Jr., RichardE. Oldenburg,Peter G. Peterson,Gifford Phillips,Nelson A. Rockefeller,*Mrs. Albrecht Saalfield,Mrs. Wolfgang Schoenborn,* Martin E. Segal,Mrs. Bertram Smith, James Thrall Soby,* Mrs.Alfred R. Stern,Mrs. Donald B. Straus,Walter N. Thayer,R.L.B. Tobin, EdwardM.M. Warburg,* Mrs.Clifton R. Wharton,Jr., MonroeWheeler,* John HayWhitney* * HonoraryTrustee Ex Officio EdwardI. Koch, Mayorof the Cityof New York; HarrisonJ. Goldin,Comptroller of the Cityof New York. Frontcover: VulgarComedy (1922) Copyright©1979, TheMuseum of ModernArt 11 West53 Street,New -

Surreal Visual Humor and Poster

Fine Arts Status : Review ISSN: 1308 7290 (NWSAFA) Received: January 2016 ID: 2016.11.2.D0176 Accepted: April 2016 Doğan Arslan Istanbul Medeniyet University, [email protected], İstanbul-Turkey http://dx.doi.org/10.12739/NWSA.2016.11.2.D0176 HUMOR AND CRITICISM IN EUROPEAN ART ABSTRACT This article focused on the works of Bosh, Brughel, Archimboldo, Gillray, Grandville, Schön and Kubin, lived during and after the Renaissance, whose works contain humor and criticism. Although these artists lived in from different cultures and societies, their common tendencies were humor and criticism in their works. Due to the conditions of the period where these artists lived in, their artistic technic and style were different from each other, which effected humor and criticism in the works too. Analyzes and comments in this article are expected to provide information regarding the humor and criticism of today’s Europe. This research will indicate solid information regarding humor and tradition of criticism in Europe through comparisons and comments on the works of the artists. It is believed that, this research is considered to be useful for academicians, students, artists and readers who interested in humour and criticism in Europe. Keywords: Humour, Criticism, Bosch, Gillray, Grandville AVRUPA SANATINDA MİZAH VE ELEŞTİRİ ÖZ Bu makale, Avrupa Rönesans sanatı dönemi ve sonrasında yaşamış Bosch, Brueghel, Archimboldo, Gillray, Grandville, Schön ve Kubin gibi önemli sanatçıların çalışmalarında görülen mizah ve eleştiri üzerine kurgulanmıştır. Bahsedilen sanatçılar farklı toplum ve kültürde yaşamış olmasına rağmen, çalışmalarında ortak eğilim mizah ve eleştiriydi. Sanatçıların bulundukları dönemin şartları gereği çalışmalarındaki farklı teknik ve stiller, doğal olarak mizah ve eleştiriyi de etkilemiştir. -

Paul Klee, Mar.13-April 2, 1930

Paul Klee, Mar.13-April 2, 1930 Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1930 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1766 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history—from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 730 FIFTHAVE NEW YORK BMHanb . PAUL K L E E VyNy-T* MARCH 13 1930 APRIL 2 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 730 FIFTH AVENUE NEW YORK ACKNOWLEDGMENT The exhibition has been made possible primarily through the generous co-operation of the artist's representatives, The Flechtheim Gallery of Berlin, and the J. B. Neumann Gallery of New York. The following have also generously lent pictures: Mr. Philip C. Johnson, Cleve land; The Gallery of Living Art, New York University; The Weyhe Gallery, New York. Thanks are extended to them on behalf of the Trustees and the Staff of the Museum of Modern Art. TRUSTEES A. CONGER GOODYEAR, PRESIDENT MISS L. P. BLISS, VICE-PRESIDENT MRS. JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR., TREASURER FRANK CROWN IN SHI ELD, SECRETARY WILLIAM T. ALDRICH FREDERIC C. BARTLETT STEPHEN C. CLARK MRS. W. MURRAY CRANE CHESTER DALE SAMUEL A. LEWISOHN DUNCAN PHILLIPS MRS. RAINEY ROGERS PAUL J. SACHS MRS. CORNELIUS J. SULIVAN ALFRED H. BARR, JR., Director J ERE ABBOTT, Associate Director 5 Note — On the front cover of this Catalog is a sim plified zinc cut of Klee's Portrait of an Equilibrist. -

Franz Marc Animals Fine Art Pages

Playing Weasels Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1909 Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: Franz Marc was a German painter and printmaker that lived from 1880 to 1916. He studied in Munich and in France. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Siberian Sheepdogs Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1910 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Post-Impressionism Interesting Fact: While serving in the German military in World War I, Marc painted tarp covers in various artistic styles, ranging “from Manet to Kandinsky” in hopes of hiding artillery. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Blue Horse I Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Deer in the Snow Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Donkey Frieze Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: Most of Marc’s work portrays animals in a very stark way, using bold colors. His style caught the attention of the art world. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Monkey Frieze Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Interesting Fact: A “frieze” is a wide horizontal painting or other decoration, often displayed on a wall near the ceiling. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Resting Cows Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com The Yellow Cow Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: The style of Expressionism was a modern form of art that began in the early 1900s. -

UNSEEN WORKS of the EUROPEAN AVANT-GARDE An

Press Release July 2020 Mitzi Mina | [email protected] | Melica Khansari | [email protected] | Matthew Floris | [email protected] | +44 (0) 207 293 6000 UNSEEN WORKS OF THE EUROPEAN AVANT-GARDE An Outstanding Family Collection Assembled with Dedication Over Four Decades To Be Offered at Sotheby’s London this July Over 40 Paintings, Sculpture & Works on Paper Led by a Rare Cubist Work by Léger & an Intimate Picasso Portrait of his Secret Lover Marie-Thérèse Pablo Picasso | Fernand Léger | Alberto Giacometti | Wassily Kandinsky | Lyonel Feininger | August Macke | Alexej von Jawlensky | Jacques Lipchitz | Marc Chagall | Henry Moore | Henri Laurens | Jean Arp | Albert Gleizes Helena Newman, Worldwide Head of Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art Department, said: “Put together with passion and enjoyed over many years, this private collection encapsulates exactly what collectors long for – quality and rarity in works that can be, and have been, lived with and loved. Unified by the breadth and depth of art from across Europe, it offers seldom seen works from the pinnacle of the Avant-Garde, from the figurative to the abstract. At its core is an exceptionally beautiful 1931 portrait of Picasso’s lover, Marie-Thérèse, an intimate glimpse into their early days together when the love between the artist and his most important muse was still a secret from the world.” The first decades of the twentieth century would change the course of art history for ever. This treasure-trove from a private collection – little known and rarely seen – spans the remarkable period, telling its story through the leading protagonists, from Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso and Alberto Giacometti to Wassily Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger and Alexej von Jawlensky. -

ALFRED KUBIN 1877 Leitmeritz/Bohemia - Zwickledt/Upper Austria 1959

LE CLAIRE KUNST SEIT 1982 ALFRED KUBIN 1877 Leitmeritz/Bohemia - Zwickledt/Upper Austria 1959 Mann mit abgeschnittener Nase Pen and black ink, wash and spray, watercolour and colour crayon on firm wove paper; c.1904-7. Signed lower right: Kubin. Inscribed in pencil at the lower left: Kopf mit abgeschnittener Nase. Annotated on the verso: Mein Werk Abb. 30 327 x 253 mm LITERATURE: Alfred Kubin, Dämonen und Nachtgesichte, Dresden 1926, fig. 30 EXHIBITION: Alfred Kubin, Kunstmuseum Winterthur 1986, no. 115, repr. p.115 This early drawing immediately evokes a sinister vision of terrifying intensity – a characteristically Kubinesque depiction of the human face. The head appears to be mummified and a gaping void indicates where the nose once was. The sparse hair with its receding hairline accentuates the outline of the mask-like face which has the strange shimmer of a fleshless skull. The drawing is loaded with undertones of death. Alfred Kubin makes frequent reference to his experience of death in his autobiography.1 His mother died when he was a boy and her early death undoubtedly left an indelible psychological legacy. He made his first drawings at about that time. Thematically, these early sheets show the emergence of a tendency towards exaggeration and a liking for visionary fantasy.2 A tremendous curiosity for eerie events guided his early art.3 The origins of his artistic development and later literary career date from a very early age.4 Kubin regarded this densely worked autonomous drawing as so important that he reproduced it in his early publication Dämonen und Nachtgesichte. -

LYONEL FEININGER Cover of the Manifesto

LYONEL FEININGER Cover of the manifesto »The01 ultimate aim of all creative Feininger’s Expressionist cathedral has three towers with star-topped spires, from which beams activity is the building,« states of light go out in various directions. The three spires stand for architecture, the arts, and the Walter Gropius’ Bauhaus manifesto. crafts. Naturally, architecture was represented by the central and tallest spire. The primacy He saw building as a social, intel- of architecture was unquestioned, and the study of architecture was to stand at the center of lectual,and symbolic activity, a education. The other arts and crafts were ancillary to it. union of genres and vocations, the But, as so often, there was a world of difference between the vision and the reality, for leveling of differences in status. The though Feininger’s visionary woodcut makes a clear affirmation, the training of architects Gothic cathedral epitomized this. played virtually no part in the early years of the Weimar Bauhaus. In 1923, Gropius was able to mount the International Architectural Exhibition, which he had put together in the context of the Bauhaus exhibition—the first presentation of modern architecture in the 1920s—but the setting up of the study of architecture as a Bauhaus training program did not take place until the Bauhaus moved to Dessau. Two versions: one goal Even before Lyonel Feininger became the first teacher to be appointed by Walter Gropius, in the spring of 1919, and to begin his activity at the newly founded Bauhaus, he was given the 1871 Born in New York on July 17 task of supplying a programmatic illustration for the Bauhaus manifesto. -

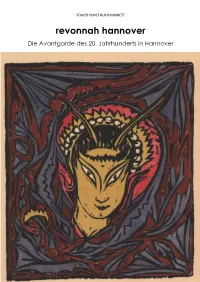

Revonnah Hannover Die Avantgarde Des 20

STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT revonnah hannover Die Avantgarde des 20. Jahrhunderts in Hannover 1 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT Katalog 3 Herbst 2018 Stader Kunst-Buch-Kabinett Antiquariat Michael Schleicher Schützenstrasse 12 21682 Hansestadt STADE Tel +49 (0) 4141 777 257 Email [email protected] Abbildungen Umschlag: Katalog-Nummern 67 und 68; Katalog-Nummer 32. Preise in EURO (€) Please do not hesitate to contact me: english descriptions available upon request. 2 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT 1 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Vorwort). I. Sonderausstellung Max Liebermann Gemälde Handzeichnungen. 1. Oktober - 5. November [1916]. Hannover, Königstr. 8. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1916, ca. 19,8 x 14,5 cm, (16) Seiten, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original-Klammerheftung. Umschlag etwas fleckig, Rückendeckel mit handschriftlichen Zahlenreihen, sonst ein gutes Exemplar. 280,-- Kestnerchronik 1, 29. - Schmied 1 (Abbildung des Umschlages Seite 238). - Literatur: Die Zwanziger Jahre in Hannover, Kunstverein, 1962. - Schmied, Wieland, Wegbereiter zur modernen Kunst, 50 Jahre Kestner Gesellschaft, 1966. - Kestnerchronik, Kestnergesellschaft, Buch 1, 2006. - REVONNAH, Kunst der Avantgarde in Hannover 1912-1933, Sprengel Museum, 2017. 2 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Text). III. Sonderausstellung Willy Jaeckel Gemälde u. Graphik. 17. Dezember 1916 - 17. Januar 1917. Hannover, Königstrasse 8. Zeitgleich mit Walter Alfred Rosam und Ludwig Vierthaler (Verzeichnis auf lose einliegendem Doppelblatt). Verkäufliche Arbeiten mit den gedruckten Preisangaben. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1917, ca. 19,7 x 14,4 cm, (16) Seiten, (4) Seiten Einlagefaltblatt als Ergänzung zum Katalog, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original- Klammerheftung (Klammern oxidiert). Im oberen Bereich alter Feuchtigkeitsschaden; die Seiten sind nicht verklebt.