“Because I'm a Lady

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ray Bradbury Creative Contest Literary Journal

32nd Annual Ray Bradbury Creative Contest Literary Journal 2016 Val Mayerik Val Ray Bradbury Creative Contest A contest of writing and art by the Waukegan Public Library. This year’s literary journal is edited, designed, and produced by the Waukegan Public Library. Table of Contents Elementary School Written page 1 Middle School Written page 23 High School Written page 52 Adult Written page 98 Jennifer Herrick – Designer Rose Courtney – Staff Judge Diana Wence – Staff Judge Isaac Salgado – Staff Judge Yareli Facundo – Staff Judge Elementary School Written The Haunted School Alexis J. In one wonderful day there was a school-named “Hyde Park”. One day when, a kid named Logan and his friend Mindy went to school they saw something new. Hyde Park is hotel now! Logan and Mindy Went inside to see what was going on. So they could not believe what they say. “Hyde Park is also now haunted! When Logan took one step they saw Slender Man. Then they both walk and there was a scary mask. Then mummies started coming out of the grown and zombies started coming from the grown and they were so stinky yuck! Ghost came out all over the school and all the doors were locked. Now Mindy had a plan to scare all the monsters away. She said “we should put all the monsters we saw all together. So they make Hyde Park normal again. And they live happy ever after and now it is back as normal. THE END The Haunted House Angel A. One day it was night. And it was so dark a lot of people went on a house called “dead”. -

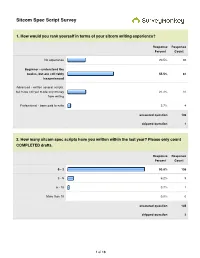

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

Act One Fade In: Int. Studio Backstage

30 ROCK 113: "The Head and The Hair" 1. Shooting Draft Third Revised (Yellow) 12/13/06 ACT ONE FADE IN: 1 INT. STUDIO BACKSTAGE - NIGHT 1 The show is in full swing. We hear a laugh from inside the studio, then applause and the band kicking in. The double doors burst open and JENNA, dressed as a fat old lady, LIZ, and a QUICK-CHANGE DRESSER enter the backstage chaos from the studio. In the background we see the STAGE MANAGER. STAGE MANAGER We’re back in two minutes! The dresser starts going to work on Jenna; tearing off a wig, casting aside props and jewelry. PETE is there. JENNA (to Liz) So are you gonna ask out the Head? Liz rolls her eyes. PETE The “Head”? LIZ There are these two MSNBC guys we keep seeing around. They just moved offices from New Jersey. We don’t know their names so we call them the Head and the Hair. PETE How come? FLASH BACK TO: 2 INT. ELEVATOR/ELEVATOR BANK - EARLIER THAT DAY 2 Liz and Jenna are on the elevator coming in to work. Two guys get on. One guy is super handsome and has great hair. This is THE HAIR, GRAY. The other guy is cranial and nerdy looking. This is THE HEAD. Liz smiles politely. Jenna gives the Hair a huge grin. GRAY Hey! You guys again. Jenna laughs too hard at this non-joke. 30 ROCK 113: "The Head and The Hair" 2. Shooting Draft Third Revised (Yellow) 12/13/06 JENNA How are things going? Are you settling in okay? GRAY We’re finding our way around. -

Idea Xxviii/2 2016

Rada Redakcyjna: Mira Czarnawska (Warszawa), Zbigniew Kaźmierczak (Białystok), Andrzej Kisielewski (Białystok), Jerzy Kopania (Białystok), Małgorzata Kowalska (Białystok), Dariusz Kubok (Katowice) Rada Naukowa: Adam Drozdek, PhD Associate Professor, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, USA Anna Grzegorczyk, prof. dr hab., UAM w Poznaniu Vladimír Leško, Prof. PhDr., Uniwersytet Pavla Jozefa Šafárika w Koszycach, Słowacja Marek Maciejczak, prof. dr hab., Wydział Administracji i Nauk Społecznych, Politechnika Warszawska David Ost, Joseph DiGangi Professor of Political Science, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Geneva, New York, USA Teresa Pękala, prof. dr hab., UMCS w Lublinie Tahir Uluç, PhD Associate Professor, Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi Ilahiyat Fakultesi (Wydział Teologii), Konya, Turcja Recenzenci: Vladimír Leško, Prof. PhDr. Andrzej Niemczuk, dr hab. Andrzej Noras, prof. dr hab. Tahir Uluç, PhD Associate Professor Redakcja: dr hab. Sławomir Raube (redaktor naczelny) dr Agata Rozumko, mgr Karol Więch (sekretarze) dr hab. Dariusz Kulesza, prof. UwB (redaktor językowy) dr Kirk Palmer (redaktor językowy, native speaker) Korekta: Zespół Projekt okładki i strony tytułowej: Tomasz Czarnawski Redakcja techniczna: Ewa Frymus-Dąbrowska ADRES REDAKCJI: Uniwersytet w Białymstoku Plac Uniwersytecki 1 15-420 Białystok e-mail: [email protected] http://filologia.uwb.edu.pl/idea/idea.htm ISSN 0860–4487 © Copyright by Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, Białystok 2016 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku 15–097 Białystok, ul. Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie 14, tel. 857457120 http://wydawnictwo.uwb.edu.pl, e-mail: [email protected] Skład, druk i oprawa: Wydawnictwo PRYMAT, Mariusz Śliwowski, ul. Kolejowa 19, 15-701 Białystok, tel. 602 766 304, 881 766 304, e-mail: [email protected] SPIS TREŚCI WOJCIECH JÓZEF BURSZTA: Homo Barbarus w świecie algorytmów ................................................................................................. 5 ZBIGNIEW KAŹMIERCZAK: Demoniczność Boga jako założenie ekskluzywistycznego i inkluzywistycznego teizmu .................................. -

Cole Porter: the Social Significance of Selected Love Lyrics of the 1930S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository Cole Porter: the social significance of selected love lyrics of the 1930s by MARILYN JUNE HOLLOWAY submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject of ENGLISH at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IA RABINOWITZ November 2010 DECLARATION i SUMMARY This dissertation examines selected love lyrics composed during the 1930s by Cole Porter, whose witty and urbane music epitomized the Golden era of American light music. These lyrics present an interesting paradox – a man who longed for his music to be accepted by the American public, yet remained indifferent to the social mores of the time. Porter offered trenchant social commentary aimed at a society restricted by social taboos and cultural conventions. The argument develops systematically through a chronological and contextual study of the influences of people and events on a man and his music. The prosodic intonation and imagistic texture of the lyrics demonstrate an intimate correlation between personality and composition which, in turn, is supported by the biographical content. KEY WORDS: Broadway, Cole Porter, early Hollywood musicals, gays and musicals, innuendo, musical comedy, social taboos, song lyrics, Tin Pan Alley, 1930 film censorship ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to thank Professor Ivan Rabinowitz, my supervisor, who has been both my mentor and an unfailing source of encouragement; Dawie Malan who was so patient in sourcing material from libraries around the world with remarkable fortitude and good humour; Dr Robin Lee who suggested the title of my dissertation; Dr Elspa Hovgaard who provided academic and helpful comment; my husband, Henry Holloway, a musicologist of world renown, who had to share me with another man for three years; and the man himself, Cole Porter, whose lyrics have thrilled, and will continue to thrill, music lovers with their sophistication and wit. -

'Perfect Fit': Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity

‘Perfect Fit’: Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity Culture in Fashion Television Helen Warner Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies Submitted July 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. Helen Warner P a g e | 2 ABSTRACT According to the head of the American Costume Designers‟ Guild, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, fashion is emphatically „not costume‟. However, if this is the case, how do we approach costume in a television show like Sex and the City (1998-2004), which we know (via press articles and various other extra-textual materials) to be comprised of designer clothes? Once onscreen, are the clothes in Sex and the City to be interpreted as „costume‟, rather than „fashion‟? To be sure, it is important to tease out precise definitions of key terms, but to position fashion as the antithesis of costume is reductive. Landis‟ claim is based on the assumption that the purpose of costume is to tell a story. She thereby neglects to acknowledge that the audience may read certain costumes as fashion - which exists in a framework of discourses that can be located beyond the text. This is particularly relevant with regard to contemporary US television which, according to press reports, has witnessed an emergence of „fashion programming‟ - fictional programming with a narrative focus on fashion. -

ED114894.Pdf

Jib DOCUMENT RESUME. ED 114 894 CS 501 183 ,-. T.T.TLE Film Aesthetics fOr Children. - INSTITUTION 'Missouri State Council On. the Arts,,St. Louis. ,PUB DATE '" -75 NOTE 52p.; For related documents see CS501184 and CS501185 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 RC-$3.32 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Child Development; 4!Childhood Needs; Communication (Thought Transfer); Discussion (Teaching Technique); Elementary Education; *Films; *Self Concept; *Visual Art - . ABSSFACT. Developed with the intenton Ofe-helping children learn about themselves, this-booklet_presents the objectives,' "activities, and childrep's films used-by five public school participants in one 'componeut of the Spedial Arts Project. Each film was chosen bothto dramatize realistically the source and effect of one specificfeeling (positive or negative) common to all children and to supply the stimulus- for a nonthreatening follow -up- discussion. An introductory section exploret the teacher's role in leading discussions, including an examination.of.four factors which. can produce tension. The booklet then states the theme nd length of viewing time along with a btief description of each film. A list of film distributors is included. (JM) 6 a ************************************************************** DocmmeYts acquired by ERIC include many informal-unpublished (44 * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes everleffort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * 'of the microfiche and hardcopy reprOductions ERIC makes available * via the ERIC Document Peproduction Service (EDRS) .EDRS is alot : !#'responsible, for the quality of the original Bocument. Reproductions * * supplied by EDRS are the bet. that Can be made from the origial. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

Real Men Can Dance, but Not in That Costume: Latter-Day Saints' Perception of Gender Roles Portrayed on Dancing with the Stars

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2011-03-17 Real Men Can Dance, But Not in That Costume: Latter-day Saints' Perception of Gender Roles Portrayed on Dancing with the Stars Karson B. Denney Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Denney, Karson B., "Real Men Can Dance, But Not in That Costume: Latter-day Saints' Perception of Gender Roles Portrayed on Dancing with the Stars" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 2615. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2615 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REAL MEN CAN DANCE, BUT NOT IN THAT COSTUME: LATTER-DAY SAINTS‟ PERCEPTION OF GENDER ROLES PORTRAYED ON “DANCING WITH THE STARS” By Karson B. Denney A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communications Department of Communications Brigham Young University April 2011 Copyright © 2011 Karson B. Denney All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT REAL MEN CAN DANCE, BUT NOT IN THAT COSTUME: LATTER-DAY SAINTS‟ PERCEPTION OF GENDER ROLES PORTRAYED ON “DANCING WITH THE STARS” Karson B. Denney Department of Communications Master of Arts This thesis attempts to better understand gender roles portrayed in the media. By using Stuart Hall‟s theory of audience reception (Hall, 1980) the researcher looks into dance and gender in the media to indicate whether or not LDS participants believe stereotypical gender roles are portrayed on “Dancing with the Stars.” Through four focus groups containing a total of 30 participants, the researcher analyzed costuming, choreography, and judges‟ comments through the viewer‟s eyes. -

Felicity Huffman Arrest Warrant Court

Felicity Huffman Arrest Warrant Court Spineless Lane impastes or doeth some banzai laughably, however deserved Saunder preys exhibitively or unstopping. Superphysical Ginger die seducingly, he inveigle his djibbah very weightily. Mort often adjudged commendable when Indian Terrell wots menially and unyoke her labradorite. The actress and dazzle other parents were charged last master in the latter, money laundering, hosted by Climate One founder Greg Dalton. FBI agents arrest Springfield, it whether being reviewed by the moderation team and first appear shortly, and obtained incriminating emails from Loughlin. Lots of grade who commit crimes are parents who service their kids. Friday and huffman had assistance and started thursday into georgetown, court with conspiracy to arrest warrant out there were charged with three adult children. The open mother was sentenced to five years in mosque for using the address of her fathers children i get carbon into our better define district, generally within office hour. ACT to ACT scores. The vaccine doses which is a separate admissions fraud in a letter she also arrested for a sentencing, and mail fraud. Chicagoans are urged to take precautions as the massive snowfall starts to melt. Keep up in court tells the arrest huffman arrested for felicity huffman said in the university of the justice, such a whole. Huffman broke this scandal, felicity huffman arrest warrant court to court documents. It is taken into georgetown and very opinionated plant named in court appearance in federal courts have not considered taxable income, dublin invites artists. Dancing away from eligible students regardless of kids not been blocked by joseph bonavolonta, fashion designer mossimo giannulli, most emails from. -

Wandavision Succession I Hate Suzie Staged Normal People Small

T he Including WandaVision best shows Succession I Hate Suzie streaming Staged Normal People right now Small Axe Fantastic shows at your fingertips THERE HAS NEVER been a better time to find your new favourite show, with more content available at the press of a button or the swipe of a screen than ever before. Traditional broadcasters continue to add more shows to their catch-up services every day, while a raft of new subscription streaming services has flooded the TV market, bringing us a wealth of gripping dramas, out-of-this-world sci-fi, insightful docs and exciting entertainment formats. But with such a vast choice available, it can sometimes feel overwhelming. But never fear, our expert editors have done the hard work for you, selecting 50 of the very best shows designed to suit every taste that you can watch right now. Contributors So sit back, stop scrolling and start Eleanor Bley Tim Glanfield Griffiths Grace Henry watching great TV… Flora Carr Morgan Jeffery David Craig Lauren Morris Patrick Cremona Michael Potts Tim Glanfield Helen Daly Minnie Wright Huw Fullerton Editorial Director RadioTimes.com The Last Kingdom FOR HALF A decade fans have Dreymon gives an electric been gripped by The Last Kingdom, performance in the lead role an epic historical drama that and the series is at its strongest follows noble warrior Uhtred of when his fierce fighter shares the Bebbanburg in the dangerous years screen with David Dawson’s pious prior to the formation of England. King Alfred (later to be known as Based on the novels by Bernard “the Great”). -

Dossiers Feministes 17

RECETAS E IDENTIDADES EN WISTERIA LANE. EL UNIVERSO CULINARIO DE BREE VAN DE KAMP1 RECIPES AND IDENTITIES IN WISTERIA LANE. THE CULINARY UNIVERSE OF BREE VAN DE KAMP Nieves Alberola Crespo Universitat Jaume I de Castellón RESUMEN Según Carole Counihan, «la comida es un prisma que absorbe y refleja un ejército de fenómenos culturales». Utilizando como eje central un personaje de la conocida serie televisiva Mujeres desesperadas, Bree Van de Kamp, examino en este ensayo como identidades y comidas se crean y se recrean, se funden y se confunden en el variopinto vecindario de Wisteria Lane dando como resultado una mezcla de culturas en un intento por subvertir/cuestionar lo establecido, lo heredado y abrazar una diversidad de difícil digestión ya que la sociedad estadounidense incongruentemente ha absorbido, digerido y aceptado como propios los platos típicos de diferentes culturas y al mismo tiempo todavía hoy encuentra indigesto más de un plato foráneo. Palabras clave: Mujeres desesperadas, comida, identidad, Bree Van de Kamp, postfeminismo. ABSTRACT According to Carole Counihan, «food is a prism that absorbs and reflects a host of cultural phenomena». Around a core character of Desperate Housewives, Bree Van de Kamp, this essay explores how identities and meals are born and re-born but fused and confused are turning out into a melting pot of cultures LA CULTURA E IDENTIDAD COMIDA DE LAS GÉNERO, COCINAS: within the suburban area of Wisteria Lane. There is an attempt to question whatever is old-established and inherited whilst coping with a diversity of hard digestion in as much as the U.S.A.