Children's Literature in Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nagroda Im. H. Ch. Andersena Nagroda

Nagroda im. H. Ch. Andersena Nagroda za wybitne zasługi dla literatury dla dzieci i młodzieży Co dwa lata IBBY przyznaje autorom i ilustratorom książek dziecięcych swoje najwyższe wyróżnienie – Nagrodę im. Hansa Christiana Andersena. Otrzymują ją osoby żyjące, których twórczość jest bardzo ważna dla literatury dziecięcej. Nagroda ta, często nazywana „Małym Noblem”, to najważniejsze międzynarodowe odznaczenie, przyznawane za twórczość dla dzieci. Patronem nagrody jest Jej Wysokość, Małgorzata II, Królowa Danii. Nominacje do tej prestiżowej nagrody zgłaszane są przez narodowe sekcje, a wyboru laureatów dokonuje międzynarodowe jury, w którego skład wchodzą badacze i znawcy literatury dziecięcej. Nagrodę im. H. Ch. Andersena zaczęto przyznawać w 1956 roku, w kategorii Autor, a pierwszy ilustrator otrzymał ją dziesięć lat później. Na nagrodę składają się: złoty medal i dyplom, wręczane na uroczystej ceremonii, podczas Kongresu IBBY. Z okazji przyznania nagrody ukazuje się zawsze specjalny numer czasopisma „Bookbird”, w którym zamieszczane są nazwiska nominowanych, a także sprawozdanie z obrad Jury. Do tej pory żaden polski pisarz nie otrzymał tego odznaczenia, jednak polskie nazwisko widnieje na liście nagrodzonych. W 1982 roku bowiem Małego Nobla otrzymał wybitny polski grafik i ilustrator Zbigniew Rychlicki. Nagroda im. H. Ch. Andersena w 2022 r. Kolejnych zwycięzców nagrody im. Hansa Christiana Andersena poznamy wiosną 2022 podczas targów w Bolonii. Na długiej liście nominowanych, na której jest aż 66 nazwisk z 33 krajów – 33 pisarzy i 33 ilustratorów znaleźli się Marcin Szczygielski oraz Iwona Chmielewska. MARCIN SZCZYGIELSKI Marcin Szczygielski jest znanym polskim pisarzem, dziennikarzem i grafikiem. Jego prace były publikowane m.in. w Nowej Fantastyce czy Newsweeku, a jako dziennikarz swoją karierę związał również z tygodnikiem Wprost oraz miesięcznikiem Moje mieszkanie, którego był redaktorem naczelnym. -

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 94 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #307 - ORIGINAL ART BY MAUD HUMPHREY FOR GALLANT LITTLE PATRIOTS #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus (The Doll House) #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus #195 - Detmold Arabian Nights #526 - Dr. Seuss original art #326 - Dorothy Lathrop drawing - Kou Hsiung (Pekingese) #265 - The Magic Cube - 19th century (ca. 1840) educational game Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON RARE TUCK RAG “BLACK” ABC 5. ABC. (BLACK) MY HONEY OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. -

Electronic Solutions to the Problems of Monograph Publishing

Electronic Solutions to the Problems of Monograph Publishing By Anthony Watkinson Resource: The Council for Museums, Archives and Libraries 2001 Abstract Electronic Solutions to the Problems of Monograph Publishing examines the suggestion that the so-called monograph crisis can be overcome by making use of the possibilities of electronic publishing. Research monographs are the preferred way in which scholarship is communicated in most disciplines in the humanities and some in the social sciences. The problems faced by publishers influence the practices of the scholars themselves. This study examines the nature of the crisis in the print environment, the aspirations of scholarly publishers in the electronic environment and the attitudes of and impacts on other parts of the information chain. There is as yet little experience of electronic monographs, so the emphasis is on the projections of the various players and on the major experiments that are being funded. There is nevertheless consideration of the practical aspects of making content available in digital form. No immediate solution is presented but there are pointers to fruitful future developments. Anthony Watkinson is an independent consultant with three decades of experience in scholarly publishing. He was a pioneer in putting scholarly journals online. He is a visiting professor in information science at City University, London Library and Information Commission Research Report 109 British National Bibliography Research Fund Report 101 © Resource: The Council for Museums, Archives and Libraries 2001 The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Resource: The Council for Museums, Archives and Libraries BR/010 ISBN 0 85386 267 2 ISSN 1466-2949 ISSN 0264-2972 Available from the Publishers Association at www.publishers.org.uk ii Contents: PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vi A: Introduction and Context 1. -

(D1) 05/01/2015 Anthony Byrne Fine Wines Limit

DOCUMENT TYPES (B) TO (L) (CONT'D) ANROMA MANAGEMENT CONSULTANCY 06819392 (D1) 05/01/2015 ANTHONY BYRNE FINE WINES LIMITED 01713692 (D2) 05/01/2015 LIMITED ANTHONY CLARET INTERNATIONAL LTD 06479258 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANRUI TRADING CO., LTD 07463687 (D1) 02/01/2015 ANTHONY CONSTRUCTION LIMITED 00825380 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANSA CONSULTING LTD 07528126 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANTHONY COTTAGES (PROPERTY 06449568 (D2) 01/01/2015 ANSADOR LIMITED 01681135 (D1) 05/01/2015 MANAGEMENT) COMPANY LIMITED ANSADOR HOLDINGS LIMITED 04253203 (D1) 05/01/2015 ANTHONY CROFT EZEKIEL LIMITED 02736529 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANSAR RAHMAN LIMITED 08344458 (D2) 05/01/2015 ANTHONY DE JONG & CO LTD 04584791 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANSBROS CATERING CONSULTANCY LIMITED 08328505 (D2) 05/01/2015 ANTHONY DONOVAN LIMITED 03632969 (D1) 05/01/2015 ANSCO BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT LIMITED 04731291 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANTHONY D. WILSON LTD. 07554212 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANSEL DEVELOPMENTS LIMITED 06514029 (D1) 06/01/2015 ANTHONY HALL HAIRDRESSING LTD 08827706 (D2) 05/01/2015 ANSELL CONSULTING LIMITED 08349931 (D2) 06/01/2015 ANTHONY HILDEBRAND LIMITED 07975020 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANSELL MURRAY LIMITED 07586001 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANTHONY HUGHES DRIVE HIRE LIMITED 07871476 (D2) 31/12/2014 ANSFORD ACADEMY TRUST 07657806 (D1) 06/01/2015 ANTHONY JAMES OFFICE GROUP LTD 07570608 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANSGATE BARNES HOLDCO LTD 08697007 (C2) 06/01/2015 ANTHONY JEFFERIES LIMITED 07871752 (D2) 05/01/2015 ANSH CONSULTING LIMITED 06810059 (D2) 03/01/2015 ANTHONY K WEBB LIMITED 06548206 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANSHEL LIMITED 05385255 (D1) 31/12/2014 ANTHONY -

Swedish Literature on the British Market 1998-2013: a Systemic

Swedish Literature on the British Market 1998-2013: A Systemic Approach Agnes Broomé A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UCL Department of Scandinavian Studies School of European Languages, Culture and Society September 2014 2 I, Agnes Broomé, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. …............................................................................... 3 4 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the role and function of contemporary Swedish fiction in English translation on the British book market in the period 1998-2013. Drawing on Bourdieu’s Field Theory, Even Zohar’s Polysystem Theory and DeLanda’s Assemblage Theory, it constructs a model capable of dynamically describing the life cycle of border-crossing books, from selection and production to marketing, sales and reception. This life cycle is driven and shaped by individual position-takings of book market actants, and by their complex interaction and continual evolution. The thesis thus develops an understanding of the book market and its actants that deliberately resists static or linear perspectives, acknowledging the centrality of complex interaction and dynamic development to the analysis of publishing histories of translated books. The theoretical component is complemented by case studies offering empirical insight into the model’s application. Each case study illuminates the theory from a different angle, creating thereby a composite picture of the complex, essentially unmappable processes that underlie the logic of the book market. The first takes as its subject the British publishing history of crime writer Liza Marklund, as well as its wider context, the Scandinavian crime boom. -

Lesson Horrid Henry

LESSON PLAN Name : School: Trysil, Norway Date: Time of lesson: 90 minutes or more. Class: 6 Level: 11 – 12 years No. of students: Unit: Textbook: Lesson Objectives: 1. To read 2. To understand 3. To write 4. To learn Assumptions: The students can use grammar. Anticipated problems: Explain what a biography is. Materials: Working sheets, paper version or computer version. Internet. Key Activity 1 Aim: To understand, and use the grammar right. Procedure: Interaction: One by one. 1. Read the text. 2. Answer the questions in full sentences. 3. Grammar. - Fill in the missing adverbs. - Write six sentences using these adverbs of time. 4. Grammar. - Irregular verbs. Fill in the missing verb forms. 5. Writing. - Write a biography about a person you know, or would like to know. (Make sure you write your text in paragraphs.) 1. Read this text! Horrid Henry’s holiday Horrid Henry hated holidays. Henry’s idea of a super holiday was sitting on a sofa eating crisps and watching TV. Unfortunately, his parents usually had other plans. Once they took him to see some castles. But there were no castles. There were only piles of stones and broken walls. “Never again,” said Henry. The next year he had to go to a lot of museums. “Never again, “said Mum and Dad. Last year they went to the seaside. “The sun is too hot,” Henry whined. “The water is too cold,” Henry whined. “The food is too yucky,” Henry grumbled. “The bed is lumpy,” Henry moaned. The great day arrived at last. Horrid Henry, Perfect Peter, Mum and Dad boarded the ferry for France. -

Die Geschichte Vom Kleinen Onkel

Barbro Lindgren, Eva Eriksson, Angelika Kutsch Die Geschichte vom kleinen Onkel Im Herzen ist Platz für mehr als einen! Ein Bilderbuch- Kleinod über die Freundschaft. Es war einmal ein kleiner Onkel, der war sehr einsam. Niemand kümmerte sich um ihn, obwohl er so nett war. Alle fanden ihn zu klein. Und dann fanden sie noch, dass er dumm aussah. Es half nichts, dass er dauernd den Hut abnahm und "Guten Tag" sagte. Es war trotzdem niemand nett zu ihm. Bis ihm eines Tages ein Hund zulief und ihm zärtlich seine kalte Nase in die Hand legte. Die zu Herzen Altersempfehlung: ab 4 Jahren gehende Geschichte vom Allein- und Zusammensein ist die ISBN: 978-3-7891-7549-7 Bilderbuchausgabe des Kinderbuch-Klassikers von Barbro Erscheinungstermin: Lindgren, mit farbigen Bildern der vielfach ausgezeichneten 2012-02-01 Illustratorin Eva Eriksson. Seiten: 32 Verlag: Oetinger AUTOR Barbro Lindgren Barbro Lindgren, 1937 in Schweden geboren, besuchte die Kunstschule in Stockholm und schreibt Bücher für Kinder und Erwachsene. Für ihr Gesamtwerk erhielt sie u.a. den schwedischen Astrid-Lindgren-Preis und den Nils-Holgersson-Preis; für den Deutschen Jugendliteraturpreis wurde sie nominiert. Ihre charmanten Bilderbuchgeschichten vom kleinen "Max" und den Erlebnissen in seinem Kinderalltag, kongenial von Eva Eriksson illustriert, zählen bereits zu den Bilderbuch-Klassikern. "Knappe Worte, drollige Bilder und die Kinder lieben es, weil hier ein Stück ihrer Lebenswirklichkeit abgebildet wird. Diese Büchlein sind unschlagbar", schreibt dazu die Saarbrücker Zeitung. Für weitere informationen kontaktieren Sie bitte: Judith Kaiser ([email protected]) © Verlagsgruppe Oetinger Service GmbH https://www.oetinger.de ILLUSTRATOR Eva Eriksson Eva Eriksson, 1949 in Schweden geboren, begann nach der Geburt ihrer Kinder, Bilderbücher zu schreiben und zu illustrieren. -

PDF Download Horrid Henry and the Scary Sitter Ebook

HORRID HENRY AND THE SCARY SITTER Author: Francesca Simon,Tony Ross Number of Pages: 85 pages Published Date: 01 Sep 2009 Publisher: Sourcebooks, Inc Publication Country: Naperville, United States Language: English ISBN: 9781402217814 DOWNLOAD: HORRID HENRY AND THE SCARY SITTER Horrid Henry and the Scary Sitter PDF Book - -- Choice. It was placed at the head of China's Seven Military Classics upon the collection's creation in 1080 by Emperor Shenzong of Song, and has long been the most influential strategy text in East Asia. These are but a few of the wealth of fascinating observations contained here. Service-Oriented and Cloud Computing: Second European Conference, ESOCC 2013, Malaga, Spain, September 11-13, 2013, ProceedingsThis two-volume set, LNCS 9658 and 9659, constitutes the thoroughly refereed proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Web-Age Information Management, WAIM 2016, held in Nanchang, China, in June 2016. " They always seem to have plenty of time, money, and energy to fulfill their goals and dreams. Janet Zadina discusses multiple brain pathways for learning and provides practical advice for creating a brain-compatible classroom. And it demonstrates that taking barrier freedom into account in the early planning stages of a project need not lead to additional costs compared to "classical" construction and design. Some people handle deviating from the plan with ease, while the majority struggle. The book contains discussions of more than 800 new research studies and articles on early childhood development that have been published since the last edition. Vegan Mexican Cookbook he does exactly that. The ranker, a central component in every search engine, is responsible for the matching between processed queries and indexed documents. -

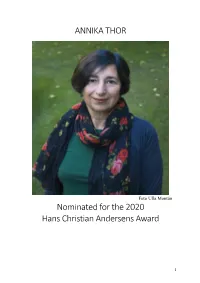

ANNIKA THOR Nominated for the 2020 Hans Christian Andersens

ANNIKA THOR Foto Ulla Montán Nominated for the 2020 Hans Christian Andersens Award 1 Nomination Dear Jury Members and IBBY Secretariat We are delighted to nominate Author Annika Thor to the Hans Christian Andersen Award in the author category 2020. When the Board of IBBY Sweden decided to nominate the writer Annika Thor for the H C Andersen Award 2020, the principal argument was her strong advocacy for the human rights of children and young adults to be treated with dignity and respect. In her authorship, Thor centres on what it means to be human in relation to identity and belonging. The individual's struggle to find a place in existence is a motif, and the quests for love and community as well as loneliness are central concerns. Thor's texts draw attention to how migrants and refugee children are treated in their new context and social environments, in which identity and belonging are created in interaction with others. With gripping realism and insight into children's way of approaching reality, she depicts not least how refugees perceive themselves and are perceived by others as well as the experience of being viewed as an object or reduced to being part of a group without individuality. In the historical novel sequel about the Steiner girls, En ö i havet [A faraway island,] (1996), Näckrosdammen [The Lily Pond] (1997), Havets Djup [Deep Sea] (1998) and Öppet hav [Open Sea] (1999), Thor deals with themes that are as central today as during the pogroms in World War II. In an historical context she portrays how young people's identity, social and cultural belonging can develop. -

HCA Shortlist Press Release 2020, with Noms

20 January 2020 IBBY Announces the Shortlist for the 2020 Hans Christian Andersen Awards #HCA2020 IBBY, the International Board on Books for Young People is proud to announce the shortlist for the 2020 Hans Christian Andersen Award – the world’s most prestigious award for the creators of children’s and youth literature: Authors: María Cristina Ramos from Argentina, Bart Moeyaert from Belgium, Marie-Aude Murail from France, Farhad Hassanzadeh from Iran, Peter Svetina from Slovenia, and Jacqueline Woodson from the USA. Illustrators: Isabelle Arsenault from Canada, Seizo Tashima from Japan, Sylvia Weve from the Netherlands, Iwona Chmielewska from Poland, Elena Odriozola from Spain, and Albertine from Switzerland. Junko Yokota from the USA. is the 2020 jury president, and the following experts comprised the jury: Mariella Bertelli (Canada), Denis Beznosov (Russia), Tina Bilban (Slovenia), Yasuko Doi (Japan), Nadia El Kholy (Egypt), Viviane Ezratty (France), Eva Kaliskami (Greece), Robin Morrow (Australia), Cecilia Ana Repetti (Argentina), and Ulla Rhedin (Sweden). Elda Nogueira (Brazil) represented the IBBY President and Liz Page acted as Jury Secretary. The criteria used to assess the nominations included the aesthetic and literary quality as well as freshness and innovation; the ability to engage children and to stretch their curiosity and creative imagination; diversity of expressions of aesthetic, and the continuing relevance of the works to children and young people. The Award is based on the entire body of work. After the meeting Yokota said, “The jury deliberated at the International Youth Library in Munich to consider the 34 author nominees and 36 illustrator nominees from member nations of IBBY. -

List of Films Set in Berlin

LisListt of ffilmsilms sesett in Berlin From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This is a list of films whose setting is Berlin, Germany. Contents 1 1920s 2 1930s 3 1940s 4 1950s 5 1960s 6 1970s The world city Berlin is setting and filming location of 7 1980s numerous movies since the beginnings of the silent film 8 1990s era. 9 2000s 10 2010s 11 See also 1920s 1922 Dr. Mabuse the Gambler ( ( Dr Dr.. Mabuse, dederr SpielSpieler er ), 1922 - first (silent) film about the character Doctor Mabuse from the novels of Norbert Jacques, by Fritz Lang. 1924 The Last Laugh ( ( Der Letzte Mann), 1924 - The aging doorman at a Berlin hotel is demoted to washroom attendant but gets the last laugh, by F.W. Murnau. 1925 Varieté ( (Variety), 1925 - Circus melodrama set in Berlin, with the circus scenes in the Berlin Wintergarten, by EwEwalaldd AnAndrédré DDuupontpont.. Slums of Berlin ( ( Di Diee Verrufenen), 1925 - an engineer in Berlin is released from prison, but his father throws him out, his fiancée left him and there is no chance to find work. Directed by Gerhard Lamprecht. 1926 Di Diee letzte DrDroschkeoschke vvonon BeBerlirlinn, 1926 - showing the life of an old coachman in Berlin still driving the droshky during the time when the automobile arises. Directed by Carl Boese. 1927 Ber Berlin:lin: Symphony of a GGreatreat City ( ( Ber Berlin:lin: DiDiee Sinfonie der GroßsGroßstadt tadt ), 1927 - Expressionist documentary film of 1920s Berlin by Walter Ruttmann. Metropolis, 1927 - Berlin-inspired futuristic classic by Fritz Lang. 1928 Refuge ( ( Zuflucht ), 1928 - a lonely and tired man comes home after several years abroad, lives with a market-woman in Berlin and starts working for the Berlin U-Bahn. -

What Is Literature? a Definition Based on Prototypes

Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session Volume 41 Article 3 1997 What is literature? A definition based on prototypes Jim Meyer SIL-UND Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/sil-work-papers Part of the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Jim (1997) "What is literature? A definition based on prototypes," Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session: Vol. 41 , Article 3. DOI: 10.31356/silwp.vol41.03 Available at: https://commons.und.edu/sil-work-papers/vol41/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session by an authorized editor of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What is Literature? A Definition Based on Prototypes Jim Meyer Most definitions of literature have been criterial definitions, definitions based on a list of criteria which all literary works must meet. However, more current theories of meaning take the view that definitions are based on prototypes: there is broad agreement about good examples that meet all of the prototypical characteristics, and other examples are related to the prototypes by family resemblance. For literary works, prototypical characteristics include careful use of language, being written in a literary genre (poetry, prose fiction, or drama), being read aesthetically, and containing many weak implicatures. Understanding exactly what literature is has always been a challenge; pinning down a definition has proven to be quite difficult.