William Shakespeare (1546-1616), with a Particular Focus on the Tempest and As You Like It; J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Journal of Applied Arts Studies Aesthetic and Symbolic

Available online at www.ijapas.org International Journal of Applied Arts Studies IJAPAS 2(2) (2017) 69–78 Aesthetic and Symbolic Analysis of the Manuscript Illustration Alexander the Great (Sikandar) in Conversation with WakWak Tree (Talking Tree) in Shahnameh Demot Seyed Hasan Soltania*, Armita Saadatmandb aProfessor, Department of Art, Tehran University, Tehran, Iran bM.Sc. Student, Department of Art and Architecture, Yazd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Yazd, Iran Received 19 April 2017; revised 9 May 2017; accepted 24 May 2017 Abstract Combining Persian miniature and literature together has been influential in the recent decades. Illustrated Shahnameh Demot (Book of Kings, Great Persian Epic), which is known as the most valuable illustrated artwork in the first Tabrīz school, is considered to be the special style of Persian Illustration or Miniature during Mughal Ilkhanid era, taking advantage of interaction between literature and painting. This article attempts to examine artistic and visual qualities of the illustration “Alexander the Great (Sikandar) in conversation with WakWak tree” in Ilkhanid era. A descriptive-analytic approach is used to investigate the interaction between literature and illustration. The research results indicated that the tree is a concept existing beyond human mind, and that it is embodied through symbolism. In Shahnameh, WakWak tree or Talking tree is a symbolic tree where Alexander is in conversation with WakWak tree and the tree foresees his future. As the art is always influenced by the ideology underscoring the era, it could be alleged that mythological thought has been influential in the artistic structure of illustration, and it has been turned into an aesthetic language that has led to the reflection of the evolution of poetry in the illustration. -

Fall 2012 Newsletter Page 1 Or WALE on Facebook an Invitation from Our

WALE: an interest group of WLA WALE Info… Fall 2012 Newsletter Page 1 http://wale.wla.org/ or WALE on Facebook An Invitation from our WALE Chair… We are just under 2 months away from the WALE Conference in Chelan. I am so very proud of all the work the conference committee has put into this conference. We anticipate this to be one of the best conferences we’ve ever put on. We are also very excited to be able to offer two scholarships consisting of full conference registration and lodging for October 29 & 30, thanks to a match- ing donation from WLA. The Scholarship deadline is September 14 and full details may be found at http://2012waleconference.wla.org/scholarships- grants/ . While I am thrilled about this year’s conference, I would like everyone to be thinking about next year’s conference now. We need enthusiastic people willing to take a leadership role in conference planning. We will be counting on you to volunteer as Conference Chair, chair a committee, or work on a committee. It’s challenging work, but very rewarding and quite fun. If you don’t want to take on a committee by yourself, consider grabbing a friend and working as co-chairs. WALE is a fantastic organization, but we are only as strong as our membership, and we count on you keep us moving forward. If you have any questions about volunteering, or would like to step up to the challenge of con- ference planning, please send me an email. We look forward to hearing from you. -

HFPA Newsletter 2004 September

Hawaii Foster Parent Association E PŪLAMA NĀ KEIKI “Cherish the Children” September 2004 VOLUME 9, ISSUE 3 AROUND THE WORLD IN CFSR REPORTS GIVE NATIONAL DATA AN EVENING Foster Parents often do not Receive Notice; Are Denied Opportunity to Be Heard Reception and Wine Bill Grimm Tasting at Indigo’s Youth Law News, April-June 2004 This article is adapted from the fourth in a series of articles Wednesday, November 10, 2004 published by the National Center for Youth Law, analyzing 5:30 p.m.— 8:00 p.m. the federal Child and Family Services Reviews. The articles, as well as the citations for this article, can be found at Tickets: $75 www.youthlaw.org. “The foster parent … of a child and any pre-adoptive Proceeds to support the work of the Hawaii Foster Parent parent or relative providing care for the child are pro- Association. Call 808-263-0920 for ticket information. vided with notice of, and an opportunity to be heard in, any review or hearing to be held with respect to the child ….” The Hawaii Foster Parent Association The Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997, Sec. 104 website is live! Check it out at The opportunity to participate in hearings concerning the child placed in their home is an ex- www.hawaiifosterparent.org. plicit federal mandate given foster parents, pre- adoptive parents, and relatives caring for foster chil- On the home page, you’ll find dren. Congress enacted these provisions, termed a list of the three most recently- “notice and opportunity to be heard rights for caregiv- posted articles. -

Genre Bending Narrative, VALHALLA Tells the Tale of One Man’S Search for Satisfaction, Understanding, and Love in Some of the Deepest Snows on Earth

62 Years The last time Ken Brower traveled down the Yampa River in Northwest Colorado was with his father, David Brower, in 1952. This was the year his father became the first executive director of the Sierra Club and joined the fight against a pair of proposed dams on the Green River in Northwest Colorado. The dams would have flooded the canyons of the Green and its tributary, Yampa, inundating the heart of Dinosaur National Monument. With a conservation campaign that included a book, magazine articles, a film, a traveling slideshow, grassroots organizing, river trips and lobbying, David Brower and the Sierra Club ultimately won the fight ushering in a period many consider the dawn of modern environmentalism. 62 years later, Ken revisited the Yampa & Green Rivers to reflect on his father's work, their 1952 river trip, and how we will confront the looming water crisis in the American West. 9 Minutes. Filmmaker: Logan Bockrath 2010 Brower Youth Awards Six beautiful films highlight the activism of The Earth Island Institute’s 2011 Brower Youth Award winners, today’s most visionary and strategic young environmentalists. Meet Girl Scouts Rhiannon Tomtishen and Madison Vorva, 15 and 16, who are winning their fight to green Girl Scout cookies; Victor Davila, 17, who is teaching environmental education through skateboarding; Alex Epstein and Tania Pulido, 20 and 21, who bring urban communities together through gardening; Junior Walk, 21 who is challenging the coal industry in his own community, and Kyle Thiermann, 21, whose surf videos have created millions of dollars in environmentally responsible investments. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Allen Tate (1899-1979) Seasons of the Soul (1944) to the Memory of John Peale Bishop, 1892-1944 Allor Porsi Ola Mano Un Poco

Allen Tate (1899-1979) Seasons of the Soul (1944) To the memory of John Peale Bishop, 1892-1944 Allor porsi ola mano un poco avante, e colsi un ramicel da un gran pruno; e il tronco suo grido: Perche mi schiante? I. SUMMER Summer, this is our flesh, The body you let mature; If now while the body is fresh You take it, shall we give The heart, lest heart endure The mind's tattering Blow of greedy claws? Shall mind itself still live If like a hunting king It falls to the lion's jaws? Under the summer's blast The soul cannot endure Unless by sleight or fast It seize or deny its day To make the eye secure. Brothers-in-arms, remember The hot wind dries and draws With circular delay The flesh, ash from the ember, Into the summer's jaws. It was a gentle sun When, at the June solstice Green France was overrun With caterpillar feet, No head knows where its rest is Or may lie down with reason When war's usurping claws Shall take the heart escheat-- Green field in burning season To stain the weevil's jaws. The southern summer dies Evenly in the fall: We raise our tired eyes Into a sky of glass, Blue, empty, and tall Without tail or head Where burn the equal laws For Balaam and his ass Above the invalid dead, Who cannot lift their jaws. When was it that the summer (Daylong a liquid light) And a child, the new-comer, Bathed in the same green spray, Could neither guess the night? The summer had no reason; Then, like a primal cause It had its timeless day Before it kept the season Of time's engaging jaws. -

Angela M. Ross

The Princess Production: Locating Pocahontas in Time and Place Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ross, Angela Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 20:51:52 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194511 THE PRINCESS PRODUCTION: LOCATING POCAHONTAS IN TIME AND PLACE by Angela M. Ross ________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE CULTURAL AND LITERARY STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2008 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Angela Ross entitled The Princess Production: Locating Pocahontas in Time and Place and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/03/2008 Susan White _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/03/2008 Laura Briggs _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/03/2008 Franci Washburn Final approval -

Abyssal Larva Adherer Aerial Servant Aberrant Abomination

Lairs Web Enhancement The lairs present here were written by names of traders to use the tunnel are set every so often hold the ceiling Jeff Harkness, Gary Schotter and John Stater. in place. Lanterns hang every 100 yards to light the path. A group of travelers entered the tunnel a week ago but never came out. Three people later found an abandoned cart at the tunnel’s halfway point, but no people. Rumors are flying that the Root Run is haunted. Fear has halted the trade route, and the trade group that maintains the tunnel is Aberrant offering a 500 gp reward for the safe return of the missing travelers. Cyst Fist’s Pass The reward won’t ever be collected. The missing traders met a gruesome fate when an abyssal harvester broke through a hole in reality as they A small troop of 16 aberrants from the Cyst Fist Tribe have set up a camp passed. The grasping tentacles dragged the victims into the Abyss where at the crest of the mountain pass. Their leader is the biggest of the tribe, a they were devoured. The abyssal harvester currently has four of its thick mountain of a creature named Furgristle. This group has journeyed down tentacles stretched across the tunnel’s passage to snare new victims. The from their caves higher up in the mountains to raid and pillage, hoping tentacles appear to be tree roots in the semi-darkness until they rise to to bring back items to help the tribe get through the coming winter. attack. -

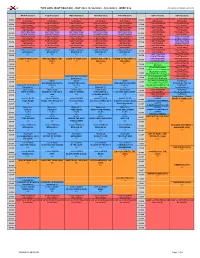

MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM MON (4/26/2021) TUE (4/27/2021) WED (4/28/2021) THU (4/29/2021) FRI (4/30/2021) SAT (5/1/2021) SUN (5/2/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO -

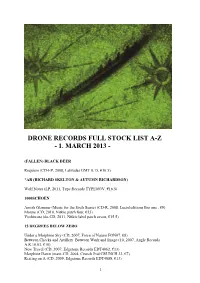

13-03-01 Full Stock List

DRONE RECORDS FULL STOCK LIST A-Z - 1. MARCH 2013 - (FALLEN) BLACK DEER Requiem (CD-EP, 2008, Latitudes GMT 0:15, €10.5) *AR (RICHARD SKELTON & AUTUMN RICHARDSON) Wolf Notes (LP, 2011, Type Records TYPE093V, €16.5) 1000SCHOEN Amish Glamour (Music for the Sixth Sense) (CD-R, 2008, Lucioleditions llns one , €9) Moune (CD, 2010, Nitkie patch four, €13) Yoshiwara (do-CD, 2011, Nitkie label patch seven, €15.5) 15 DEGREES BELOW ZERO Under a Morphine Sky (CD, 2007, Force of Nature FON07, €8) Between Checks and Artillery. Between Work and Image (10, 2007, Angle Records A.R.10.03, €10) New Travel (CD, 2007, Edgetone Records EDT4062, €13) Morphine Dawn (maxi-CD, 2004, Crunch Pod CRUNCH 32, €7) Resting on A (CD, 2009, Edgetone Records EDT4088, €13) 1 21 GRAMMS Water-Membrane (CD, 2012, Greytone grey009, €12) 23 SKIDOO The Culling is Coming (CD, 2003, LTM Publishing / Boutique BOUCD 6604, €15) Seven Songs (CD, 2008, LTM Publishing LTMCD 2528, €14.5) Seven Songs (do-LP, 2012, LTM Publishing LTMLP 2528, €29.5) 2KILOS & MORE 9,21 (mCD-R, 2006, Taalem alm 37, €5) 8floors lower (CD, 2007, Jeans Records 04, €13) 3/4HADBEENELIMINATED The Religious Experience (LP, 2007, Soleilmoon Recordings SOL 147, €25) Theology (CD, 2007, Soleilmoon Recordings SOL 148, €19.5) Oblivion (CD, 2010, Die Schachtel DSZeit11, €14) 400 LONELY THINGS same (LP, 2003, Bronsonunlimited BRO 000 LP, €12) 5F-X The Xenomorphians (CD, 2007, Hands Production D112, €15) 5IVE Hesperus (CD, 2008, Tortuga TR-037, €16) 5UU'S Crisis in Clay (CD, 1997, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu2, €14) Hunger's Teeth -

Hiking Trails a Guide to Florida’S Top Hiking Trails Florida Hiking Trails

FloridaHiking Trails A Guide to Florida’s Top Hiking Trails Florida Hiking Trails Hiking Florida Blessed with an abundance of sunshine and foliage, Florida presents the perfect destination for hikers to explore and experience the Sunshine State’s natural and historic diversity. In Florida, hiking opens your eyes to the dynamic environmental changes that occur as elevation increases from below sea level to only 345 feet. With more than 80 different natural communities, Florida presents more botanical diversity than any other state on the East Coast, and does so with grace along its thousands of miles of hiking trails. From the tropical hammocks of the Keys to the pine forests of the Panhandle, Florida’s hiking trails provide more to explore, including 10,000 years of cultural history. From short self-guided nature trails to overnight hiking trips along the National Scenic Trail, Florida has it all. You’ll find hiking trails for every season and for every experience. So grab your pack and water bottle, and Hike Florida! How to use this Guide: Each destination listed in the brochure may have multiple types of trails. Each trail mentioned for the destination is color-coded based on the type of trail. Trails marked in blue are gentle strolls on nature trails. Green signifies the opportunity to take a longer hike, of up to 10 miles in a day. Trails marked red are best for an overnight backpacking experience. The destination itself is color- coded to signify the easiest type of hike available at that destination. Parking Picnic Area Restrooms Camping Area Wheelchair Access Cabins Water Fountain Bird Watching Food and/or Bottled Water All times listed are EST (Eastern Standard Time) unless otherwise noted CST (Central Standard Time). -

Albuquerque Morning Journal, 09-24-1922 Journal Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 9-24-1922 Albuquerque Morning Journal, 09-24-1922 Journal Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_mj_news Recommended Citation Journal Publishing Company. "Albuquerque Morning Journal, 09-24-1922." (1922). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ abq_mj_news/698 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALBOQUERQUE NG JOURNAL i niii v.i until - r PAGES TODAY I.V v yicai:, 1922. ci.xxiv. Xo. 8. Albuquerque, New Mexico, Sunday, September 24, J.O two sections PRICE F. CUNTS. r n nil i n r" n 1 1 1 1 1 1 1-- r-- E Peaeeful ta of Kesnal Pasha, I IjHAHL tu Will L i EIGHT MEN DIE: ALLIES CONCEDE 1 Who Cause Another War iay STATE BANKERS' I ACCIDENTS TURKISH CLAIMS - ST RAIL STRIKERS HI HORROR ASSOCIATION'S PLANES EAST IS ISSUED RY II. S. ! Grand Jury Report. Accom- - NEW PRESIDENT Bomber With Six Passen-ner- s TALK ENDS panying Indictments,' Burns at Mineola; 2 i j Criticizes State, County Balloon Attackers Fall ati Authorities. Albuqucrquean Is Elected i Nationalist Assured Judge Wilkerson in Chicago Holds Shopmen's and Town ; Baltimore. Party Annual of the j at Meeting Possession of tastenv Strike a in of 111., 23 tho As Conspiracy Restraint Trade, Marion, Sept.