Chapter 1. Source and Behaviour of Arsenic in Natural Waters 1.1 Importance of Arsenic in Drinking Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mg2sio4) in a H2O-H2 Gas DANIEL TABERSKY1, NORMAN LUECHINGER2, SAMUEL S

Goldschmidt2013 Conference Abstracts 2297 Compacted Nanoparticles for Evaporation behavior of forsterite Quantification in LA-ICPMS (Mg2SiO4) in a H2O-H2 gas DANIEL TABERSKY1, NORMAN LUECHINGER2, SAMUEL S. TACHIBANA1* AND A. TAKIGAWA2 2 2 1 , HALIM , MICHAEL ROSSIER AND DETLEF GÜNTHER * 1 Department of Natural History Sciences, Hokkaido 1ETH Zurich, Department of Chemistry and Applied University, N10 W8, Sapporo 060-0810, Japan. Biosciences, Laboratory of Inorganic Chemistry (*correspondence: [email protected]) (*correspondence: [email protected]) 2Carnegie Institution of Washington, Department of Terrestrial 2Nanograde, Staefa, Switzerland Magnetism, 5241 Broad Branch Road NW, Washington DC, 20015 USA. Gray et al. did first studies of LA-ICPMS in 1985 [1]. Ever since, extensive research has been performed to Forsterite (Mg2SiO4) is one of the most abundant overcome the problem of so-called “non-stoichiometric crystalline silicates in extraterrestrial materials and in sampling” and/or analysis, the origins of which are commonly circumstellar environments, and its evaporation behavior has referred to as elemental fractionation (EF). EF mainly consists been intensively studied in vacuum and in the presence of of laser-, transport- and ICP-induced effects, and often results low-pressure hydrogen gas [e.g., 1-4]. It has been known that in inaccurate analyses as pointed out in, e.g. references [2,3]. the evaporation rate of forsterite is controlled by a A major problem that has to be addressed is the lack of thermodynamic driving force (i.e., equilibrium vapor reference materials. Though the glass series of NIST SRM 61x pressure), and the evaporation rate increases linearly with 1/2 have been the most commonly reference material used in LA- pH2 in the presence of hydrogen gas due to the increase of ICPMS, heterogeneities have been reported for some sample the equilibrium vapor pressure. -

And Gas-Based Geochemical Prospecting Of

Water- and gas-based geochemical prospecting of geothermal reservoirs in the Tarapacà and Antofagasta regions of northern Chile Tassi, F.1, Aguilera, F.2, Vaselli, O.1,3, Medina, E.2, Tedesco, D.4,5, Delgado Huertas, A.6, Poreda, R.7 1) Department of Earth Sciences, University of Florence, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121, Florence, Italy 2) Departamento de Ciencias Geológicas, Universidad Católica del Norte, Av. Angamos 0610, 1280, Antofagasta, Chile 3) CNR-IGG Institute of Geosciences and Earth Resources, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121, Florence, Italy 4)Department of Environmental Sciences, 2nd University of Naples, Via Vivaldi 43, 81100 Caserta, Italy 5) CNR-IGAG National Research Council, Institute of Environmental Geology and Geo-Engineering, Pzz.e A. Moro, 00100 Roma, Italy. 6) CSIS Estacion Experimental de Zaidin, Prof. Albareda 1, 18008, Granada, Spain. 7) Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, 227 Hutchinson Hall, Rochester, NY 14627, U.S.A.. Studied area The Andean Central Volcanic Zone, which runs parallel the Central Andean Cordillera crossing from North to This study is mainly focused on the geochemical characteristics of water and gas South the Tarapacà and Antofagasta regions of northern Chile, consists of several volcanoes that have shown phases of thermal fluids discharging in several geothermal areas of northern Chile historical and present activity (e.g. Tacora, Guallatiri, Isluga, Ollague, Putana, Lascar, Lastarria). Such an intense (Fig. 1); volcanism is produced by the subduction process thrusting the oceanic Nazca Plate beneath the South America Plate. The anomalous geothermal gradient related to the geodynamic assessment of this extended area gives El Tatio, Apacheta, Surire, Puchuldiza-Tuya also rise to intense geothermal activity not necessarily associated with the volcanic structures. -

Geochemical Modeling of Iron and Aluminum Precipitation During Mixing and Neutralization of Acid Mine Drainage

minerals Article Geochemical Modeling of Iron and Aluminum Precipitation during Mixing and Neutralization of Acid Mine Drainage Darrell Kirk Nordstrom U.S. Geological Survey, Boulder, CO 80303, USA; [email protected] Received: 21 May 2020; Accepted: 14 June 2020; Published: 17 June 2020 Abstract: Geochemical modeling of precipitation reactions in the complex matrix of acid mine drainage is fundamental to understanding natural attenuation, lime treatment, and treatment procedures that separate constituents for potential reuse or recycling. The three main dissolved constituents in acid mine drainage are iron, aluminum, and sulfate. During the neutralization of acid mine drainage (AMD) by mixing with clean tributaries or by titration with a base such as sodium hydroxide or slaked lime, Ca(OH)2, iron precipitates at pH values of 2–3 if oxidized and aluminum precipitates at pH values of 4–5 and both processes buffer the pH during precipitation. Mixing processes were simulated using the ion-association model in the PHREEQC code. The results are sensitive to the solubility product constant (Ksp) used for the precipitating phases. A field example with data on discharge and water composition of AMD before and after mixing along with massive precipitation of an aluminum phase is simulated and shows that there is an optimal Ksp to give the best fit to the measured data. Best fit is defined when the predicted water composition after mixing and precipitation matches most closely the measured water chemistry. Slight adjustment to the proportion of stream discharges does not give a better fit. Keywords: geochemical modeling; acid mine drainage; iron and aluminum precipitation; schwertmannite; basaluminite 1. -

Field Excursion Report 2010

Presented at “Short Course on Geothermal Drilling, Resource Development and Power Plants”, organized by UNU-GTP and LaGeo, in Santa Tecla, El Salvador, January 16-22, 2011. GEOTHERMAL TRAINING PROGRAMME LaGeo S.A. de C.V. GEOTHERMAL ACTIVITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN SOUTH AMERICA: SHORT OVERVIEW OF THE STATUS IN BOLIVIA, CHILE, ECUADOR AND PERU Ingimar G. Haraldsson United Nations University Geothermal Training Programme Orkustofnun, Grensasvegi 9, 108 Reykjavik ICELAND [email protected] ABSTRACT South America holds vast stores of geothermal energy that are largely unexploited. These resources are largely the product of the convergence of the South American tectonic plate and the Nazca plate that has given rise to the Andes mountain chain, with its countless volcanoes. High-temperature geothermal resources in Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador and Peru are mainly associated with the volcanically active regions, although low temperature resources are also found outside them. All of these countries have a history of geothermal exploration, which has been reinvigorated with recent changes in global energy prices and the increased emphasis on renewables to combat global warming. The paper gives an overview of their main regions of geothermal activity and the latest developments in the geothermal sector are reviewed. 1. INTRODUCTION South America has abundant geothermal energy resources. In 1999, the Geothermal Energy Association estimated the continent’s potential for electricity generation from geothermal resources to be in the range of 3,970-8,610 MW, based on available information and assuming the use of technology available at that time (Gawell et al., 1999). Subsequent studies have put the potential much higher, as a preliminary analysis of Chile alone assumes a generation potential of 16,000 MW for at least 50 years from geothermal fluids with temperatures exceeding 150°C, extracted from within a depth of 3,000 m (Lahsen et al., 2010). -

Arsenite Oxidation by a Hydrogenobaculum Sp. Isolated from Yellowstone National Park by Jessica Donahoe-Christiansen a Thesis Su

Arsenite oxidation by a Hydrogenobaculum sp. isolated from Yellowstone National Park by Jessica Donahoe-Christiansen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Land Resources and Environmental Sciences Montana State University © Copyright by Jessica Donahoe-Christiansen (2002) Abstract: A novel Hydrogenobaculum sp. was isolated from an acid-sulfate-chloride geothermal spring in Yellowstone National Park (YNP), WY,USA that had previously been shown to contain microbial populations engaged in arsenite oxidation. Acid-sulfate-chloride thermal springs are a prominent spring type in the Yellowstone geothermal complex and provide unique habitats to study chemolithotrophy where iron, sulfur, arsenic, and perhaps hydrogen gas represent the predominant potential electron donors for generating energy. The organism (designated H55) is an obligate microaerophilic chemolithoautotroph that grows exclusively on hydrogen gas as an electron donor. The optimum temperature and pH for H55 are 55-60°C and 3.0, respectively, and the 16S rDNA sequence of H55 is 98% identical to Hydrogenobaculum acidophilum. Whole cells of H55 displayed Michaelis-Menten type kinetics when oxidizing arsenite, with an estimated Km of 80μM arsenite and a Vmax of 1.47 pM arsenite oxidized / min. (for 1.0 x 10 6 cells per ml). The native habitat of H55 contains large amounts of ferric iron in the stream sediments and high concentrations of aqueous hydrogen sulfide, with concentrations of the latter negatively correlated with arsenite oxidation in the spring. Both chemical species were examined for their contribution to, or influence of, overall (i.e. biotic plus abiotic) stream arsenic redox activity by comparing their effects with arsenite oxidation activities of pure cultures of H55. -

Federal Register/Vol. 67, No. 101/Friday, May 24, 2002/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 67, No. 101 / Friday, May 24, 2002 / Notices 36645 along Monument Creek from any future Service, the California Department of and sulfur underground mining development. Fish and Game, and the Nevada operations, in Alpine County, Only one federally listed species, the Division of Environmental Protection, California. Anaconda developed the threatened Preble’s meadow jumping announces the release for public review former underground mine into an open mouse, occurs onsite and has the of the Leviathan Mine Natural Resource pit sulfur mine and operated the Mine potential to be adversely affected by the Damage Assessment Plan—Public through 1962. Anaconda sold the Mine project. To mitigate impacts that may Release Draft (Assessment Plan). The in early 1963, but no further mining result from incidental take, the HCP Plan was developed by the Leviathan operations took place thereafter. provides mitigation for the residential Mine Council Natural Resource Releases of hazardous substances site by protection of the Monument Trustees, consisting of representatives of from the Mine began in the 1950s and Creek corridor onsite and its associated the Tribe and agencies listed above, to continue today. Infiltration of riparian areas from all future assess injuries to natural resources precipitation into and through the adits development through the enhancement resulting from releases of hazardous (tunnels from the former underground of 0.5 acre through native grass planting, substances from the Leviathan Mine in mine), open pit, and overburden piles, shrub planting, weed control, Alpine County, California. The along with direct contact of mine wastes preservation in a native and unmowed Assessment Plan describes the proposed with surface waters, has created acid condition, and the placement of the approach for determining and mine drainage (AMD), which has been proposed building site closer to the road quantifying natural resource injuries released, and continues to be released and farther away from mouse habitat. -

Mining's Toxic Legacy

Mining’s Toxic Legacy An Initiative to Address Mining Toxins in the Sierra Nevada Acknowledgements _____________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Sierra Fund would like to thank Dr. Carrie Monohan, contributing author of this report, and Kyle Leach, lead technical advisor. Thanks as well to Dr. William M. Murphy, Dr. Dave Brown, and Professor Becky Damazo, RN, of California State University, Chico for their research into the human and environmental impacts of mining toxins, and to the graduate students who assisted them: Lowren C. McAmis and Melinda Montano, Gina Grayson, James Guichard, and Yvette Irons. Thanks to Malaika Bishop and Roberto Garcia for their hard work to engage community partners in this effort, and Terry Lowe and Anna Reynolds Trabucco for their editorial expertise. For production of this report we recognize Elizabeth “Izzy” Martin of The Sierra Fund for conceiving of and coordinating the overall Initiative and writing substantial portions of the document, Kerry Morse for editing, and Emily Rivenes for design and formatting. Many others were vital to the development of the report, especially the members of our Gold Ribbon Panel and our Government Science and Policy Advisors. We also thank the Rose Foundation for Communities and the Environment and The Abandoned Mine Alliance who provided funding to pay for a portion of the expenses in printing this report. Special thanks to Rebecca Solnit, whose article “Winged Mercury and -

Energy, Water and Alternatives – Chilean Case Studies

A Global Context and Shared Implications • Change • Uncertainty • Ambiguity Social • Technical Challenge Technical • Expansion • Constraint • Knowledge • Rapid Pace Suzanne A. Pierce Research Assistant Professor Assistant Director Center for International Energy & Environmental Policy Digital Media Collaboratory Jackson School of Geosciences Center for Agile Technology The University of Texas at Austin The University of Texas at Austin ‘All the instances of scientific development and practice . are as much embedded in politics and cultures as they are creations of the researchers, practitioners, and industries.’ (Paraphrased from Heymann, 2010; Dulay, unpublished image) Common Pool Resources Come into Conflict Integrated Water Resources Management Collaborative processes meld the use of scientific information with citizen participation and technical decision support systems Finding rigorous and effective approaches to science- based resource management and dialogue. IWRM Case Study – Northern Chile Coyahuasi Copper Mine February 2012 Mining Water Energy Multi-Scale Complexity Global demand for Copper drives localized use of energy and water resources Energy and Water Primary Resource Candidates Geothermal: Estimated 3,300 and 16,000 MW potential estimated by the Energy Ministry. Key sites throughout country with highest potential sites currently at Puchuldiza, Tatio, and Tolhuaca. Playa lake: an arid zone feature that is transitional between a playa, which is completely dry most of the year, and a lake (Briere, 2000). In this study, a salar is an internally drained evaporative basin with surface water occurring mostly from spring discharge. Energy Context Installed Capacity: 15.420 MW NextGen: 33.024 MW Per Ministerio de Energía, Perez-Arce, May 2011 Renewables Recurso Eólico Recurso Solar Recurso Hidrológico Recurso Geotérmico (Concesiones) (En desarrollo) Per Ministerio de Energía, Perez-Arce, May 2011 Geothermal Energy Resource Development • Chile has about 3000 volcanoes along the Andes, and ~150 are active. -

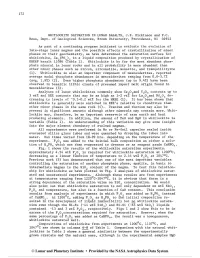

O Lunar and Planetary Institute Provided by the NASA Astrophysics Data System WHITLOCKITE SATURATION

WHITLOCKITE SATURATION IN LUNAR BASALTS, J.E. Dickinson and P.C. Hess, Dept. of Geological Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912 As part of a continuing program initiated to evaluate the evolution of late-stage lunar magmas and the possible effects of crystallization of minor phases on their geochemistry, we have determined the saturation surface for whitlockite, Ca (PO ), in a liquid composition produced by crystallization of KREEP basalt 15386 lf~able1). Whitlockite is by far the most abundant phos- phate mineral in lunar rocks and in all probability is more abundant than other minor phases such as zircon, zirccnolite, monazite, and tranquillityite (1). Whitlockite is also an important component of mesosiderites, reported average modal phosphate abundances in mesosiderites ranging from 0.0-3.7% (avg. 1.9%) (2). Even higher phosphate abundances (up to 9.4%) have been observed in basaltic lithic clasts of presumed impact melt origin found in mesosiderites (3). Analyses of lunar whitlockites commonly show Ce203and Y203 contents up to 3 wt% and REE contents that may be as high as 1-2 wt% for La203and Nd203 de- creasing to levels of -0.1-0.2 wt% for the HREE (1). It has been shown that whitlockite is generally more enriched in REE's relative to chondrites than other minor phases in the same rock (4). Uranium and thorium may also be present in significant amounts although other minerals may contain more. Whit- lockite may, therefore, be an important reservoir of rare earth and heat producing elements. In addition, the amount of FeO and MgO in whitlockite is variable (Table 1). -

Validation of Zeolites to Maximize Ammonium and Phosphate Removal from Anaerobic Digestate by Combination of Zeolites in Ca and Na Forms Page 1

Validation of zeolites to maximize ammonium and phosphate removal from anaerobic digestate by combination of zeolites in Ca and Na forms Page 1 Abstract Ammonium and phosphate are fundamental nutrients for human life, but their excess in water can lead to eutrophication, an uncontrolled growth of biomass with a consequent deficit of oxygen (hypoxia) that can be really dangerous for water life. This excess is principally due to human activities such as industry and agriculture (detergents, fertilizers) and the problem is expected to grow during next years. Then, it is necessary to find an efficient, simple and low cost technology able to remove the nutrients from water in order to avoid environmental damages. Moreover, the population growth, the constant improvement in agriculture and the consequent increase in fertilizers demand have made the recovery of nutrient from water a real need, as it has been estimated that a 20% of the total needs of Europe could be recovered from wastewaters. Although both ammonium and phosphate have to be recovered from wastewater, their simultaneous removal by means of one adsorbent material has rarely been reported hitherto. The merit of using one material for the simultaneous removal is obvious, even if it has not been achieved yet. In general, most of the solutions proposed for the simultaneous removal of ammonium and phosphate are based on the use of two types of reagents. A large list of removal technologies, ranging from biological to physic-chemical methods, have been widely studied: in this work, zeolites in Ca and Na forms were evaluated as sorbents for phosphate and ammonium from synthetic water and real anaerobic digestate. -

Hydrothermal Synthesis of Molybdenum Based Oxides for The

Hydrothermal synthesis of molybdenum based oxides for the application in catalysis Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER NATURWISSENSCHAFTEN (Dr. rer. nat.) Fakultät für Chemie und Biowissenschaften Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT) - Universitätsbereich genehmigte DISSERTATION von Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Kirsten Schuh aus Mainz Dekan: Prof. Dr. Peter Roesky Referent: Prof. Dr. Jan-Dierk Grunwaldt Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Anker Degn Jensen Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 17. April 2014 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements I owe many thanks to a lot of people who have helped, supported and encouraged me during my doctoral studies, not just scientifically but also personally. First I would like to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Jan-Dierk Grunwaldt for the opportunity to complete my doctoral studies in his group and for providing me with a very interesting and diversified topic. I am grateful for the scientific freedom he gave me, the possibility to spend several months at the Technical University of Denmark as well as University of Zurich and for the opportunity to attend international conferences. I am grateful to Dr. Wolfgang Kleist for his scientific help especially with presentations and publications making the manuscripts reader friendly. I would also like to thank Prof. Dr. Anker Degn Jensen for agreeing to be my co- supervisor, for very helpful corrections and suggestions of abstracts, manuscripts and presentations and for giving me the opportunity to spend four months in his group at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), where I felt very welcome. I am especially grateful for the help of Dr. Martin Høj, who put the selective oxidation set- up at DTU into operation, tested several of my samples for selective oxidation of propylene and performed TEM measurements of my FSP samples. -

Monazite, Rhabdophane, Xenotime & Churchite

Monazite, rhabdophane, xenotime & churchite: Vibrational spectroscopy of gadolinium phosphate polymorphs Nicolas Clavier, Adel Mesbah, Stephanie Szenknect, N. Dacheux To cite this version: Nicolas Clavier, Adel Mesbah, Stephanie Szenknect, N. Dacheux. Monazite, rhabdophane, xenotime & churchite: Vibrational spectroscopy of gadolinium phosphate polymorphs. Spec- trochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, Elsevier, 2018, 205, pp.85-94. 10.1016/j.saa.2018.07.016. hal-02045615 HAL Id: hal-02045615 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02045615 Submitted on 26 Feb 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Monazite, rhabdophane, xenotime & churchite : vibrational spectroscopy of gadolinium phosphate polymorphs N. Clavier 1,*, A. Mesbah 1, S. Szenknect 1, N. Dacheux 1 1 ICSM, CEA, CNRS, ENSCM, Univ Montpellier, Site de Marcoule, BP 17171, 30207 Bagnols/Cèze cedex, France * Corresponding author: Dr. Nicolas CLAVIER ICSM, CEA, CNRS, ENSCM, Univ Montpellier Site de Marcoule BP 17171 30207 Bagnols sur Cèze France Phone : + 33 4 66 33 92 08 Fax : + 33 4 66 79 76 11 [email protected] - 1 - Abstract : Rare-earth phosphates with the general formula REEPO4·nH2O belong to four distinct structural types: monazite, rhabdophane, churchite, and xenotime.