Thanisch2016vol1.Pdf (1.755Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume II

7+( &(/7,& (1&<&/23(',$ 92/80( ,, . T H E C E L T I C E N C Y C L O P E D I A © HARRY MOUNTAIN VOLUME II UPUBLISH.COM 1998 Parkland, Florida, USA The Celtic Encyclopedia © 1997 Harry Mountain Individuals are encouraged to use the information in this book for discussion and scholarly research. The contents may be stored electronically or in hardcopy. However, the contents of this book may not be republished or redistributed in any form or format without the prior written permission of Harry Mountain. This is version 1.0 (1998) It is advisable to keep proof of purchase for future use. Harry Mountain can be reached via e-mail: [email protected] postal: Harry Mountain Apartado 2021, 3810 Aveiro, PORTUGAL Internet: http://www.CeltSite.com UPUBLISH.COM 1998 UPUBLISH.COM is a division of Dissertation.com ISBN: 1-58112-889-4 (set) ISBN: 1-58112-890-8 (vol. I) ISBN: 1-58112-891-6 (vol. II) ISBN: 1-58112-892-4 (vol. III) ISBN: 1-58112-893-2 (vol. IV) ISBN: 1-58112-894-0 (vol. V) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mountain, Harry, 1947– The Celtic encyclopedia / Harry Mountain. – Version 1.0 p. 1392 cm. Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-58112-889-4 (set). -– ISBN 1-58112-890-8 (v. 1). -- ISBN 1-58112-891-6 (v. 2). –- ISBN 1-58112-892-4 (v. 3). –- ISBN 1-58112-893-2 (v. 4). –- ISBN 1-58112-894-0 (v. 5). Celts—Encyclopedias. I. Title. D70.M67 1998-06-28 909’.04916—dc21 98-20788 CIP The Celtic Encyclopedia is dedicated to Rosemary who made all things possible . -

Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Vol.117C, Pp.65-99

Gleeson P. (2017) Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, vol.117C, pp.65-99. Copyright: This is the author’s accepted manuscript of an article that has been published in its final definitive form by the Royal Irish Academy, 2017. Link to article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3318/priac.2017.117.04 Date deposited: 07/04/2017 Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Luigne Breg and the origins of the Uí Néill By Patrick Gleeson, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University Email: [email protected] Phone: (+44) 01912086490 Abstract: This paper explores the enigmatic kingdom of Luigne Breg, and through that prism the origins and nature of the Uí Néill. Its principle aim is to engage with recent revisionist accounts of the various dynasties within the Uí Néill; these necessitate a radical reappraisal of our understanding of their origins and genesis as a dynastic confederacy, as well as the geo-political landsape of the central midlands. Consequently, this paper argues that there is a pressing need to address such issues via more focused analyses of local kingdoms and political landscapes. Holistic understandings of polities like Luigne Breg are fundamental to framing new analyses of the genesis of the Uí Néill based upon interdisciplinary assessments of landscape, archaeology and documentary sources. In the latter part of the paper, an attempt is made to to initiate a wider discussion regarding the nature of kingdoms and collective identities in early medieval Ireland in relation to other other regions of northwestern Europe. -

Loughs Carra, Mask and Corrib; Resources, Borders and Passageways

Loughs Carra, Mask and Corrib; resources, borders and passageways A National Heritage Week 2020 Project by the Joyce Country and Western Lakes Heritage Network Introduction: Loughs Carra, Mask and Corrib are all connected with all their waters draining into the Atlantic Ocean. Their origins lie in the surrounding bedrock and the moving ice that dominated the Irish landscape. Today they are landscape icons, angling paradise and drinking water reservoirs but they have also shaped the communities on their shores. This project, the first of the Joyce Country and Western Lakes Heritage Network, explores the relationships that the people from the local towns and villages have had with these lakes, how they were perceived, how they were used and how they have been embedded in their history. The project consists of a series of short articles on various subjects that were composed by heritage officers of the local community councils and members of the local historical societies. They will dwell on the geological origin of the lakes, evidence of the first people living on their shores, local traditions and historical events and the inspiration that they offered to artists over the years. These articles are collated in this document for online publication on the Joyce Country and Western Lakes Geopark Project website (www.joycecountrygeoparkproject.ie) as well as on the website of the various heritage societies and initiatives of the local communities. Individual articles – some bilingual as a large part of the area is in the Gaeltacht – will be shared over social media on a daily basis for the duration of National Heritage Week. -

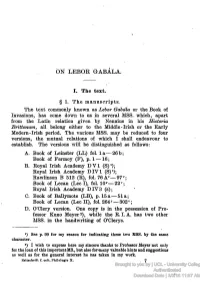

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

The Speckled Booklet of the Macegans Page - 2

The Speckled Booklet of the MacEgans Page - 2 The Speckled Booklet of The Mac Egans No. 1 Edited by Liam Egan & Michael J. S. Egan Transcribed from the original by G.K. & S.P. Egan, Clan Egan Association Australia, August 2000 with the permission of the Editor M.J.S. Egan The Speckled Booklet of the MacEgans Page - 3 DEDICATION To our kinsfolk at home and abroad Cover design by Brother Timothy O'Neill, F.S.C.—Scribe of the Egan Clan Association, Candelabra featured in the Leabhar Breac. The Speckled Booklet of the MacEgans Page - 4 Contents Foreword 1. Our Coats of Arms 2. Our Ancestral Castles 3. Our Scribes, Artists and Poets 4. Our contribution to Religion and Politics 5. Stories of Irish Kinsfolk 6. Stories of our Emigrant Kinsfolk 7. Egans of today 8. Genealogy Corner 9. Miscellaneous 10. Advertisements The Speckled Booklet of the MacEgans Page - 5 FOREWORD One of the most outstanding medieval Irish manuscripts still extant is the Leabhar Breac—the Speckled Book of the MacEgans which was written before 1411. It is now a prized possession of the Royal Irish Academy, Dublin. It will not be considered presumptuous to call this production 'The Speckled Booklet' as it is our tribute to our forbears who left such an imprint on the history of Law and Learning in Ireland. As you will see, the articles appearing in the booklet are of particular interest to people of the names MacEgan, Egan, Eagan and Keegan. Because the MacEgans were a family interested in their family history and genealogy from the earliest times, it is not surprising that the formation of our Clan Association has evoked such interest amongst our kith and kin at home and abroad. -

Literature and Learning in Early Medieval Meath

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Literature and learning in early medieval Meath Author(s) Downey, Clodagh Publication Date 2015 Downey, Clodagh (2015) 'Literature and Learning in Early Publication Medieval Meath' In: Crampsie, A., and Ludlow, F(Eds.). Information Meath History and Society: Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County. Dublin : Geography Publications. Publisher Geography Publications Link to publisher's http://www.geographypublications.com/product/meath-history- version society/ Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/7121 Downloaded 2021-09-26T15:35:58Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. CHAPTER 04 - Clodagh Downey 7/20/15 1:11 PM Page 1 CHAPTER 4 Literature and learning in early medieval Meath CLODAGH DOWNEY The medieval literature of Ireland stands out among the vernacular literatures of western Europe for its volume, its diversity and its antiquity, and within this treasury of cultural riches, Meath holds a prominence greatly disproportionate to its geographical extent, however that extent is reckoned. Indeed, the first decision confronting anyone who wishes to consider this subject is to define its geographical limits: the modern county of Meath is quite a different entity to the medieval kingdom of Mide from which it gets its name and which itself designated different areas at different times. It would be quite defensible to include in a survey of medieval literature those areas which are now under the administration of other modern counties, but which may have been part of the medieval kingdom at the time that that literature was produced. -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark. -

Without Contraries There Is No Progression

Högskolan Dalarna Department of English h 05 English C Essay Supervisor: Ellen Matlok-Ziemann Sources for the Dualistic Role and Perception of Women in Celtic Legends Michal Matynia 820609-P459 Norra Järnvägsgatan 20 791 35 Falun [email protected] 1 Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................... 2 Chaos and Order, Religion and Social Structure. ......................................................... 5 Woman as Nature ............................................................................................................. 6 Woman as Goddess........................................................................................................... 9 Heterogeneity of Celtic Women in the World of Men................................................. 12 Women Within and Beyond the Binary Perspective. .................................................. 19 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................... 26 Bibliography .................................................................................................................... 28 2 INTRODUCTION There are two morphological archetypes…expression of order, coherence, discipline, stability on the one hand; expression of chaos, movement, vitality, change on the other. Common to morphology of outer and inner processes, there are basic polarities recurring in physical phenomena, in the organic world and in the human -

Order of Celtic Wolves Lesson 5

ORDER OF CELTIC WOLVES LESSON 5 Introduction Welcome to the fifth lesson. You are now over a third of your way into the lessons. This lesson has took quite a bit longer than I anticipated to come together. I apologise for this, but whilst putting research together, we want the OCW to be as accurate as possible. One thing that I often struggle with is whether ancient Druids used elements in their rituals. I know modern Druids use elements and directions, and indeed I have used them as part of ritual with my own Grove and witnessed varieties in others. When researching, you do come across different viewpoints and interpretations. All of these are valid, but sometimes it is good to involve other viewpoints. Thus, I am grateful for our Irish expert and interpreter, Sean Twomey, for his input and much of this topic is written by him. We endeavour to cover all the basics in our lessons. However, there will be some topics that interest you more than others. This is natural and when you find something that sparks your interest, then I recommend further study into whatever draws you. No one knows everything, but having an overview is a great starting point in any spiritual journey. That said, I am quite proud of the in-depth topics we have put together, especially on Ogham. You also learn far more from doing exercises than any amount of reading. Head knowledge without application is like having a medical consultation and ignoring specialist advice. In this lesson, we are going to look at Celtic artefacts and symbols, continue with our overview of the Book of Invasions, the magick associated with the Cauldron and how to harness elemental magick. -

The Connachta of Táin Bó Cúailnge

Studia Celtica Posnaniensia, Vol 2 (1), 2017 doi: 10.1515/scp-2017-0003 THE CONNACHTA OF TÁIN BÓ CÚAILNGE ROMANAS BULATOVAS National University of Ireland, Maynooth ABSTRACT Advance in archaeology in the latter half of the 20th century rekindled interest in Táin Bó Cúailnge as a historical source and put the question of real-life identities of its main protagonists back on agenda. Despite the existing orthodoxy that the saga reflects fifth-century warfare between the southern Uí Néill and the Ulaid, some researchers continue questioning the role of the southern Uí Néill as well as the dates assigned to the events of the tale. In this article it is argued that the Connachta of the saga were more likely to be the northern Uí Néill. Furthermore, genealogical link between the two branches of the Uí Néill is put in doubt. Finally, it is suggested that the events of the Táin took place almost 200 years later than commonly believed. Keywords: The cattle-raid of Cooley, the Uí Néill dynasty, early medieval Ireland. 1.1. Preliminary Remarks Since T. F. O’Rahilly’s mythological approach had fallen out of favour, it became received wisdom that the Táin contains a genuine memory of warfare between Connaught and Ulster. However, researchers rarely agree which of the finer details preserved in the saga are historically accurate, most importantly the timeframe of the events the text refers to and the identities of warring factions. In a broad survey of current consensus concerning the antiquity of the Táin Ruairí Ó hUiginn presented several competing schools of thought (Ó hUiginn 1992: 32-33). -

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race Author: Thomas William Rolleston Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook 34081] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE*** MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE Queen Maev T. W. ROLLESTON MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE CONSTABLE - LONDON [8] British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London [9] PREFACE The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people. The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it. -

The Mast of Macha: the Celtic Irish and the War Goddess of Ireland

Catherine Mowat: Barbara Roberts Memorial Book Prize Winner, 2003 THE 'MAST' OF MACHA THE CELTIC IRISH AND THE WAR GODDESS OF IRELAND "There are rough places yonder Where men cut off the mast of Macha; Where they drive young calves into the fold; Where the raven-women instigate battle"1 "A hundred generous kings died there, - harsh, heaped provisions - with nine ungentle madmen, with nine thousand men-at-arms"2 Celtic mythology is a brilliant shouting turmoil of stories, and within it is found a singularly poignant myth, 'Macha's Curse'. Macha is one of the powerful Morrigna - the bloody Goddesses of War for the pagan Irish - but the story of her loss in Macha's Curse seems symbolic of betrayal on two scales. It speaks of betrayal on a human scale. It also speaks of betrayal on a mythological one: of ancient beliefs not represented. These 'losses' connect with a proposal made by Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, in The Myth of The Goddess: Evolution of an Image, that any Goddess's inherent nature as a War Goddess reflects the loss of a larger, more powerful, image of a Mother Goddess, and another culture.3 This essay attempts to describe Macha and assess the applicability of Baring and Cashford's argument in this particular case. Several problems have arisen in exploring this topic. First, there is less material about Macha than other Irish Goddesses. Second, the fertile and unique synergy of cultural beliefs created by the Celts4 cannot be dismissed and, in a short paper, a problem exists in balancing what Macha meant to her people with the broader implications of the proposal made by Baring and Cashford.