Niche-Sports-November-2020.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 53, November/December 2014

IInnssttaanntt UUppddaattee ISSUE 53 NOVEMBER/ DECEMBER 2014 To: ALL WSF MEMBER NATIONAL FEDERATIONS cc: WSF Regional Vice-Presidents, WSF Committee Members, WSA, PSA, Accredited Companies WSF ELECTS NEW BOARD Meanwhile, Hugo Hannes (Belgium) and Mohamed The 44th World Squash Federation AGM and El-Menshawy (Egypt) were re-standing and both Conference, held this year alongside the US Open in were re-elected. The third Vice-President place went Philadelphia, included a two-day conference which to Canadian Linda MacPhail, Secretary General of the featured presentations from key people from outside Pan-American Squash Federation [pictured with (L to squash to provide interesting insights and their R) Mohamed El-Menshawy, President Ramachandran experiences from the wide world of sport and related and Hugo Hannes]. organisations. WSF President N Ramachandran, commented: These included diverse topics such as governance, "Heather Deayton (pictured with Ramachandran) has digital marketing, interacting with communities and been a wonderful member of the WSF team and I am assessment solutions amongst others. very sorry to lose her. However, Linda MacPhail is a These included an exciting new film-based great addition, and it is a pleasure to welcome back programme for referee assessment and education Hugo and Mensh. which was demonstrated by Indian National Coach "These are exciting Major Maniam to the great interest of delegates. times for squash and Along with general business the centrepiece of the having spent the last AGM was the few days with -

Instant Update

Issue 20 World Squash Federation June 2008 Instant Update WSF MEETS IOC TO DISCUSS OLYMPIC BID WSF President Jahangir Khan , together with Emeritus President Susie Simcock and Secretary General Christian Leighton , met IOC Sports Director Christophe Dubi during this month's Sport Accord in Athens, to discuss Squash's bid to join the programme for the 2016 Olympic Games . The meeting was called by the IOC Sports Department with the objective of appraising the next steps regarding the 2008/09 review process and providing short-listed IFs the opportunity (individually) to ask questions on the process or other topics. The WSF was asked to name competitions that the Programme Commission should visit as part of the Observation Programme. Invitations will be extended to the 2008 Men's & Women's World Opens in Manchester in October. The presentations from short-listed IFs to the Executive Board will be made on 15-16 June 2009 in Lausanne. JAHANGIR KHAN HONOURED A touching “Spirit of Sport” award ceremony kicked off the AGM of the General Association of International Sports Federations in Athens, at which 83 IFs and international organisations were represented. The award recognises those who, through their unique commitment and humanitarian spirit, have made an exceptional and lasting contribution to the pursuit of sports excellence, sportsmanship and sport participation. WSF President Jahangir Khan received the 2008 GAISF Award from GAISF President Hein Verbruggen - alongside World Chess Federation (FIDE) Honorary President Florencio Campomanes -

99B.61 Bona Fide Contests. 1. a Person May Conduct, Without A

1 SOCIAL AND CHARITABLE GAMBLING, §99B.61 99B.61 Bona fide contests. 1. A person may conduct, without a license, any of the contests specified in subsection 2, and may offer and pay awards to persons winning in those contests whether or not entry fees, participation fees, or other charges are assessed against or collected from the participants, if all of the following requirements are met: a. A gambling device is not used in conjunction with or incident to the contest. b. The contest is not conducted in whole or in part on or in any property subject to chapter 297, relating to schoolhouses and schoolhouse sites, unless the contest and the person conducting the contest has the express written approval of the governing body of that school district. c. The contest is conducted in a fair and honest manner. d. A contest shall not be designed or adapted to permit the operator of the contest to prevent a participant from winning or to predetermine who the winner will be. e. The object of the contest must be attainable and possible to perform under the rules stated. f. If the contest is a tournament, the tournament operator shall prominently display all tournament rules. 2. A contest, including a contest in a league or tournament, is lawful only if it falls into one of the following event categories: a. Athletic or sporting events. Events in this category include basketball, volleyball, football, baseball, softball, soccer, wrestling, swimming, track and field, racquetball, tennis, squash, badminton, table tennis, rodeos, horse shows, golf, bowling, trap or skeet shoots, fly casting, tractor pulling, rifle, pistol, musket, or muzzle-loader shooting, billiards, darts, archery, and horseshoes. -

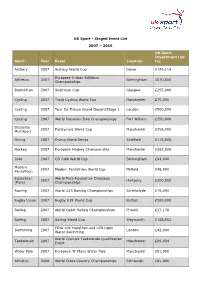

Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 Sport Year Event Location UK

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

Issue 44, May/June 2013

IInnssttaanntt UUppddaattee ISSUE 44 MAY/JUNE 2013 To: ALL WSF MEMBER NATIONAL FEDERATIONS cc: WSF Regional Vice-Presidents, WSF Committee Members, WSA, PSA, Accredited Companies ST PETERSBURG AWAITS May 29 is a critical date for squash. Last December we presented our case to the IOC’s Programme Commission and this day in May we shall do so to the IOC Executive Board in St Petersburg, Russia, along with the other shortlisted sports for the place on the programme of the 2020 Olympic Games. The presentation group will be led by WSF President Ramachandran and features our two world champions Nicol David and Ramy Ashour, whose passion and charisma are sure to impress the IOC President Jacques Rogge and his fourteen IOC Board colleagues. The bid film will be shown – it features the two players and has already been viewed nearly 110,000 times, along with the video giving a snapshot of the 185 countries that play squash (you can see both at http://www.worldsquash.org/ws/?p=10564) – along with a new film, that is being finished featuring innovation, broadcast and presentation. The spoken presentations will be accompanied by over 70 great slides illustrating the points made. What happens next is not confirmed. Originally it was stated that one sport would be recommended for ratification by the full IOC membership but indications now are that a few sports may be put forward for the final vote. That will be made clear on the evening of 29th May and we must hope that we are there for the final decision in Buenos Aires on 8th September. -

PSA Tour Rule Book

PSA Tour Rule Book Copyright © 2020 by Professional Squash Association All rights reserved vAugust 2020 Contents 1 Introduction to the Professional Squash Association 1 PSA Tour 1 PSA Mission Statement 1 PSA Tour Rule Book 1 PSA Commitments 1 PSA Contacts 2 PSA Tour 3 1.1 Tournament Levels 3 1.1.2 Defining Tournament Levels 3 1.1.2.1 On-Site Prize Money 3 1.1.2.2 Player Prize Money 3 1.1.2.3 Total Compensation 3 1.1.2.4 Mandatory Accommodation Figure 4 1.2 PSA World Tour 4 1.2.1 PSA World Championships 4 1.2.1.1 PSA World Championship Qualifying Tournament 4 1.2.1.2 Tournament Eligibility 4 1.2.2 PSA World Tour Finals 4 1.2.3 PSA World Tour Platinum 4 1.2.4 PSA World Tour Gold, Silver and Bronze 5 1.3 PSA Challenger Tour 5 1.4 WSF & PSA Satellite Tour 6 1.5 PSA Tournament Service 6 1.6 PSA Tour Calendar 6 1.6.1 PSA Tour Scheduling 6 1.6.1.1 PSA World Tour Scheduling 7 1.6.1.2 PSA Challenger Tour Scheduling 7 1.6.1.3 WSF & PSA Satellite Tour Scheduling 7 1.7 PSA Tournament Format 7 Tournament Commitment 9 2.1 Commitment to Rules 9 2.1.1 Equal Treatment of Players 9 2.2 Sanctioning Process 9 2.2.1 Tournament Registration 9 2.2.2 Sanction Fees 9 2.2.2.1 Deposits 10 2.2.3 Offers 10 2.2.4 PSA Player Contribution 10 2.2.5 SQUASHTV Fees / Rights Fees 11 2.2.6 Letter of Credit 11 2.2.7 Non-Scoring Status 11 2.2.8 Prize Money 11 2.2.8.1 Player Prize Money 11 2.2.8.2 Paying Prize Money: Western Union 11 2.2.8.3 Paying Prize Money: Cash-On-Site 11 2.2.8.4 Paying Prize Money: Tournaments in the United States 12 2.2.8.5 Paying Per Diem Payments 12 -

Squash Program

Youth Squash Program What is Squash? According to an article published in Men’s Fitness Magazine: You'll need a racquet, an opponent, a ball, and an enclosed court—most colleges and large gyms have them. Alternate hitting the ball off the front wall until someone loses the point. This happens when you allow the ball to bounce twice, or when you whack it out of bounds—below the 19-inch strip of metal (the "tin") along the bottom of the front wall, or above the red line around the top of the court. First one to 11 points wins the game; best of three or five wins the match. It may sound simple, but Squash is a challenging and rewarding game. And no one in South Jersey does it better than Greate Bay Racquet and Fitness. Why should you choose Greate Bay Racquet and Fitness Squash program? Greate Bay Racquet and Fitness is South Jersey's premiere racquet sports facility. Our full-service Squash club features: Four Squash courts o Two International Singles Courts o Two North American Doubles Courts Coaching from our full-time Squash professional Access to our Squash pro shop Lessons and clinics A track-record of successful juniors programs The best amenities for proper training; Locker rooms, Steam Room, Sauna 1 Youth Squash Program Greg Park – Squash Professional Greg Park is the Head Squash Professional at Greate Bay Racquet & Fitness Club. He is a Touring Squash Professional who is currently ranked 10th in the World and 2nd in the United States by the SDA Pro Tour. -

Worksheet Answers

Analysing sporting injuries Worksheet answers 1. Use the data in Table 1 to determine the four sports, for males and females separately, that resulted in most hospitalisations over the three-year study period. Enter into Table 2. SPORTS WITH MOST HOSPITALISATIONS SPORTS WITH MOST HOSPITALISATIONS (MALES) (FEMALE) 1. AFL netball 2. soccer basketball 3. basketball soccer 4. cricket tennis Table 2. Sports resulting in the most hospitalisations over three years (2007–2010) 2. Of course, the sport that has the highest number of hospitalisations is not necessarily the most dangerous. We need to allow for the popularity of different sports. A lot more people play soccer, for example, than hockey, so we would expect more soccer injuries than hockey. What additional data would you need to make a fair comparison between hospitalisation rates for different sports? How would you use this data? We need to know the number of males and females that play each of these sports in order to calculate the hospitalisation rate = number hospitalised / number of participants. This rate can be expressed as a fraction, percentage or per 1000 participants. 3. Use data in Table 3 to calculate the number of hospitalisations over three years, per thousand participants, for each sport. Calculate rates for male and female separately and enter into Table 4 (calculations have already been done for some sports). number of hospitalisations hospitalisation rate (per thousand participants)) = 1000 × number of participants NUMBER OF HOSPITALISATIONS HOSPITALISATIONS PER 1000 PARTICIPANTS SPORT MALE FEMALE MALE FEMALE AFL 6150 126 27.9 8.4 rugby (league/union) 399 21 ( 33.0 ) ( 11.1 ) soccer (indoor/outdoor) 1479 183 7.0 3.0 basketball 1001 316 7.0 4.7 netball 141 796 7.6 5.3 volleyball 62 22 2.3 0.9 baseball (+softball) 83 32 ( 12.4 ) ( 3.1 ) cricket (indoor/outdoor) 807 25 4.7 ( 1.5 ) hockey 215 72 10.2 ( 5.5 ) badminton 41 16 1.1 0.6 table tennis 26 14 0.8 ( 5.4 ) squash (+racquetball) 80 18 2.5 ( 3.5 ) tennis 185 151 1.2 1.1 Table 4. -

Artistic Swimming

ARTISTIC SWIMMING EVENTS Women (3) Duets Teams Highlight Mixed (1) Duets QUOTA Qualification Host NOC Total Men 7 1 8 Women 64 8 72 Total 71 9 80 athletes MAXIMUM QUOTA PER NOC EVENT Qualification Host NOC Total Duets 1 duet (2 athletes) 1 duet (2 athletes) 12 duets of 2 athletes Teams 1 team (8 athletes) 1 team (8 athletes) 8 teams of 8 athletes Highlight 1 team (8 athletes) 1 team (8 athletes) 8 teams of 8 athletes Mixed Duets 1 duet (2 athletes) 1 duet (2 athletes) 8 Duets of 2 athletes Total 9 athletes (8 women + 1 man) 9 athletes (8 women + 1 man) 80 athletes (72 women + 8 men) Athletes may register for more than one event. Eight teams with a maximum of 8 (eight) athletes each may participate in the team and highlight competition (no reserves will be allowed). Eight duets with a maximum of 2(two) athletes (one man and one woman) each may participate in the mixed duet competition (no reserves will be allowed). Twelve teams with a maximum of 24 athletes (no reserves will be allowed) may participate in the duet competition. As Host Country, Colombia automatically will qualify one team in each event, with a maximum of 9 athletes (8 women and 1 man). Athlete eligibility The athletes must have signed and submitted the Athlete Eligibility Condition Form. Only NOCs recognized by Panam Sports whose national swimming federations are affiliated with the International Swimming Federation (FINA) and the Union Americana de Natación (UANA) may enter athletes in the Cali 2021 Junior Pan American Games. -

Squash in the United States Why Squash?

SQUASH IN THE UNITED STATES WHY SQUASH? Twenty million people play squash in 185 countries. The current No. 1 male player hails from Egypt, challenged by British, French and a multitude of international stars. The No. 1 female player is from Malaysia giving the sport a truly global presence from the USA to Europe and including Asia, India and the Middle East. Squash players and fans represent a highly targeted and sought after demographic of men and women with median incomes of more than $300,000 and an average net worth of nearly $1,500,000. Nicol David Squash players are business owners and senior of Malaysia executives in upper management throughout corporate is currently ranked world America along with research physicians, architects, No. 1 in attorneys, and accountants. women’s squash. Squash players are highly educated. 98% of squash players are college graduates with 57% having graduate degrees. Eighty-five colleges sent teams to the nationals in 2013, including all the Ivys, Stanford, UVA, and Vanderbilt. Forbes Magazine has ranked squash as the “world’s No. 1 healthiest sport” ahead of rowing, running, and swimming, making an association with the sport of squash highly desirable. Adult players are engaged, passionate, and loyal. In a 2013 survey by US Squash, more than 90% of Ramy Ashour of Egypt respondents play frequently, and 65% have played for is currently ranked more than 10 years. world No. 1 in men’s squash. 2 SQUASH IN THE UNITED STATES The United States has the fastest growing squash partic- ipation of any country worldwide. -

2016 Squash & Racquetball Victoria Awards Night

2016 Squash & Racquetball Victoria Awards Night LIFE MEMBERSHIP Life Membership of Squash & Racquetball Victoria (S&RV) is a public acknowledgement of the direct contribution someone has made to squash and/or racquetball in Victoria over an extended period of time. This contribution can be in the form of playing, coaching, refereeing, administration or a general contribution. Noelle Bartling Noelle had a squash career spanning 31 years, firstly at Balwyn Squash Courts, then Camberwell, Bennetswood and later through Masters at Hunts and finally at Doncaster. She played as high as No 3 State 1 and late in her career, won an A Grade Victorian Title. She coached ladies daytime at the Golden Bowl Centre. From the 1970’s to 1990’s Noelle edited VWSRA, SRAV (now S&RV) and VMSA magazines and newsletters as well as producing numerous newspaper articles. Noelle was also a major part in the organisation (and promotion of) Australian Tours by English and South African women’s teams. She was also involved in the Trade Credits Tournaments of the early 80’s. Noelle joined the VMSA committee in 1982 and as well as organising their annual ball down to the last detail, was also the prime mover in arranging social and official functions when Melbourne hosted international events. In 1983, the VMSA hosted the Australian Open Championships. Noelle convinced Sun Alliance and Tooheys Brewery to be sponsors and was, of course, part of the daily running of the tournament. Vicki (Hoffman) Cardwell and Dean Williams won the event. She arranged an excellent report in the daily press, which was unusual publicity for squash in those days. -

2018 Coverage

2018 coverage Unrivalled highlights coverage sntv offers more cleared highlights from a wider range of sports than anyone else, offering the greatest breadth of sports coverage worldwide. Videos that inform and engage We provide our clients with the most relevant and engaging videos, either fully customisable or ready to publish directly to your audience. Global and regional sports video news Our dedicated teams fully understand what our clients are looking for, and recognise what content will drive conversations on both an international and regional level. January February March April May soccer soccer american football soccer baseball AFC Champions League Superbowl LII Chinese Super League MLB Season FA Cup Final Jan - Nov Feb Mar - Nov Apr - Oct May Copa Libertadores J.League UEFA Champions Jan - Nov rugby Mar - Dec basketball League Final RBS Six Nations NBA Playoffs May tennis Championship golf Apr - May UEFA Europa League Final ATP World Tour Feb - Mar ANA Inspiration May Jan - Nov Mar - Apr american football UEFA Women’s Champions Australian Open soccer NFL Draft League Final Jan EFL Cup Final baseball Apr May Davis Cup Feb MLB Spring Training Jan - Nov Mar ice hockey tennis Hopman Cup tennis NHL Playoffs French Open Jan Fed Cup motorsport Apr - Jun May - Jun WTA Tour Feb - Nov Jan - Oct Formula One Mar - Nov golf basketball golf golf Moto GP The Masters NBA Finals Apr European Tour Asian Tour Mar - Aug May - Jun Feb - Dec Jan - Nov MXGP Ladies European Tour motorsport golf LPGA Tour Mar - Oct Feb - Dec World Touring Car Players