James Rodriguez V. Harris County, Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

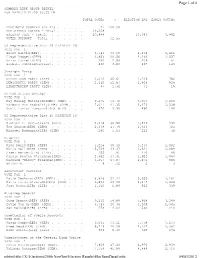

Election Summary

Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY REPT-GROUP DETAIL RUN DATE:12/01/09 03:55 PM TOTAL VOTES % ELECTION DAY EARLY VOTING PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 21) . 21 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - Total . 39,008 BALLOTS CAST - Total. 20,498 13,646 6,852 VOTER TURNOUT - Total . 52.55 US Representative Dist 25 DISTRICT 25 VOTE FOR 1 Grant Rostig(REP). 3,743 33.08 2,252 1,491 Lloyd Doggett(DEM) . 6,853 60.56 4,296 2,557 Brian Parrett(IND) . 290 2.56 209 81 Barbara Cunningham(LIB). 430 3.80 287 143 Straight Party VOTE FOR 1 REPUBLICAN PARTY (REP) . 2,010 45.61 1,226 784 DEMOCRATIC PARTY (DEM) . 2,330 52.87 1,406 924 LIBERTARIAN PARTY (LIB). 67 1.52 51 16 United States Senator VOTE FOR 1 Kay Bailey Hutchison(REP) (REP) . 9,275 54.70 6,007 3,268 Barbara Ann Radnofsky(DEM) (DEM). 7,011 41.35 4,473 2,538 Scott Lanier Jameson(LIB) (LIB) . 670 3.95 480 190 US Representative Dist 10 DISTRICT 10 VOTE FOR 1 Michael T. McCaul(REP) (REP) . 2,318 46.58 1,579 739 Ted Ankrum(DEM) (DEM) . 2,378 47.79 1,653 725 Michael Badnarik(LIB) (LIB) . 280 5.63 222 58 Governor VOTE FOR 1 Rick Perry(REP) (REP) . 5,216 30.49 3,234 1,982 Chris Bell(DEM) (DEM) . 5,709 33.37 3,621 2,088 James Werner(LIB) (LIB). 156 .91 110 46 Carole Keeton Strayhorn(IND) . 2,962 17.31 1,922 1,040 Richard "Kinky" Friedman(IND). -

WELCOME to the WORLD of ARCHITECTURE TSTU Publishing

WELCOME TO THE WORLD OF ARCHITECTURE TSTU Publishing House Учебное издание ДОБРО ПОЖАЛОВАТЬ В МИР АРХИТЕКТУРЫ Сборник текстов на английском языке Составители: ГВОЗДЕВА Анна Анатольевна НАЧЕРНАЯ Светлана Владимировна РЯБЦЕВА Елена Викторовна ЦИЛЕНКО Любовь Петровна Редактор З.Г. Чернова Компьютерное макетирование М. А. Филатовой Подписано в печать 20.05.04 Формат 60 × 84 / 16. Бумага офсетная. Печать офсетная. Гарнитура Тimes New Roman. Объем: 3,49 усл. печ. л.; 3,5 уч.-изд. л. Тираж 100 экз. С. 372М Издательско-полиграфический центр Тамбовского государственного технического университета, 392000, Тамбов, Советская, 106, к. 14 Министерство образования и науки Российской Федерации Тамбовский государственный технический университет ДОБРО ПОЖАЛОВАТЬ В МИР АРХИТЕКТУРЫ Сборник текстов на английском языке для студентов 1 курса архитектурно-строительных специальностей Тамбов Издательство ТГТУ 2004 УДК 802.0(076) ББК Ш13(Ан)я923 Д56 Рецензент: Кандидат педагогических наук Е.А. Воротнева Составители: А.А. Гвоздева, С.В. Начерная, Е.В. Рябцева, Л.П. Циленко Д56 Добро пожаловать в мир архитектуры: Сборник текстов на английском языке / Сост.: А.А. Гвоздева, С.В. Начерная, Е.В. Рябцева, Л.П. Циленко. Тамбов: Изд-во Тамб. гос. техн. ун-та, 2004. 60 с. Предлагаемые аутентичные тексты отвечают динамике современного научно- технического прогресса, специфике существующих в университете специально- стей, а также требованиям учебной программы по иностранному языку для сту- дентов очной и заочной форм обучения высших учебных заведений технического профиля. Сборник текстов предназначен для студентов первого курса архитектурно- строительных специальностей. УДК 802.0(076) ББК Ш13(Ан)я923 © Тамбовский государственный технический университет (ТГТУ), 2004 BOLSHOI THEATRE Widely considered as one of the most beautiful performance houses in the world, the Bolshoi Theatre stands as a testament to the enduring nature of the Russian character. -

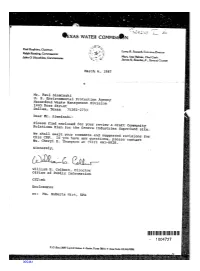

[Draft Community Relations Plan for Remedial Design

EXAS WATER COMMIS^N Paul Hopktns, Chairman Ralph Roming, Commissioner Larry R. Soward, Executive Director Mary Ann Hefner, Chief Cicrk John O. Houchins, Commissioner " James K. Rourke, J-., General Counsel March 6, 1987 Mr. Paul Sieminski U. S. Environmental Protection Agency- Hazardou1445 fccss s WastStreee t Management Division * Dallas, Texas 75202-2733 Dear Mr. Sieminski: Please find enclosed for your review a draft Community Relations Plan for the Geneva Industries Superfund site. We shall await your comments and suggested revisions for Msthi. s CheryCRPl . EI.f yoThompsou havn e anat y (512questions) 463-8028, pleas. e contact Sincerely, William E. Colbert, Director Office of Public Information CET:mk Enclosures cc: Ms. Roberta Hirt, EPA P. O. Bos I3GS7 Capital Slflt10n * Amtin. Tew* 387H * Area Code 512/463-7898 005461 COMMUNITY RELATIONfor S PLAN REMEDIAL DESIGN/REMEDIAL ACTION Geneva Industries Hazardous Waste Site Houston, Harris County, Texas March 1987 Office of Public Information Texas Water Commission 1700 North Congress Avenue Austin, Texas 78711 005462 COMMUNITY RELATIONS PLAN for REMEDIAL DESIGN/REMEDIAL ACTION Geneva Industries Hazardous Waste Site Houston, Harris County, Texas March 1987 Funding provided by a Grant from the United States Environmental CompensatioProtection n Agencand y Liabilitunder yth e AcComprehensivt of 1980 e Environmental Grant Number: V-006452 Project Manager: Jim Feeley Texas Water Commission WastInquiriese Sit: e projecAll inquiriet shoulds relatebe referred tod thtoe : Geneva Industrie""usuries s HazardouHazardouss William E. Colbert, Director Office of Public Information Texas Water Commission P.O. Box 13087, Capitol Station Austin, Texas 78711 (512) 463-8028 005463 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Overview of Community Relations Plan, B. -

BARBARA ANN RADNOFSKY [email protected]

1 BARBARA ANN RADNOFSKY [email protected] EXPERIENCE & EDUCATION: Nominee, Texas Democratic Party, State Attorney General 2010. Nominee, Texas Democratic Party, United States Senate 2006. (Winner, March Statewide Primary and April Statewide Runoff Elections, 2006) Vinson & Elkins, L. L. P. Houston, Texas (Associate 1979-1987; Partner 1987-2006). Head of Section, Alternate Dispute Resolution University of Texas School of Law, Doctor of Jurisprudence with Honors (May 1979) Albert Jones Scholar; Chairman, U.T. Board of Advocates; Fraternity: Order of the Barristers; Internship: Travis County Public Defender University of Houston, Bachelor of Arts, magna cum laude (May 1976) National Merit 4 year Academic Scholarship Languages: English, Spanish EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Practicing on both sides of the docket, BarbaraRadnofsky has been listed since 1991 in “Best Lawyers in America." She’s listed in multiple areas, on both sides of the docket, including ADR, mediation, arbitration, medical malpractice, personal injury, and health care law . An attorney since 1979, she is a mother of three, wife, teacher, and mediator. After 2006 retirement from Vinson & Elkins at age 49, she became the first woman in history to serve as the Texas Democratic U.S. Senate nominee. Barbara was the first woman at Vinson & Elkins to have children as an associate and attain partnership. She has served as lead counsel in jury trials involving commercial disputes, professional liability, tax, contractual indemnity, false arrest, malicious prosecution, assault, premises liability, insurance defense matters, pedestrian and auto accidents, Section 1983 Civil Rights disputes, worker's compensation matters, and products liability; argued successfully before the Fifth Circuit on pro bono prisoner's rights and torts matters; conducted appeals there, and in Texas state appellate courts; and represented clients in Congressional hearings and administrative tribunals. -

Cumulative Report — Official

Cumulative Report — Official Montgomery County, Texas — JOINT ELECTION — November 07, 2006 Page 1 of 11 11/16/2006 01:21 PM Total Number of Voters : 81,970 of 225,179 = 36.40% Precincts Reporting 85 of 85 = 100.00% Party Candidate Early Election Total Straight Party, Vote For 1 Republican 12,764 78.91% 17,499 77.66% 30,263 78.18% Democratic 3,287 20.32% 4,701 20.86% 7,988 20.64% Libertarian 125 0.77% 334 1.48% 459 1.19% Cast Votes: 16,176 50.60% 22,534 45.07% 38,710 58.50% United States Senator, Vote For 1 REP Kay Bailey Hutchison 23,580 75.81% 37,013 76.32% 60,593 76.12% DEM Barbara Ann Radnofsky 6,843 22.00% 10,073 20.77% 16,916 21.25% LIB Scott Lanier Jameson 682 2.19% 1,409 2.91% 2,091 2.63% Cast Votes: 31,105 97.29% 48,495 96.99% 79,600 98.15% United States Representative, District 8, Vote For 1 REP Kevin Brady 23,301 75.48% 36,464 75.67% 59,765 75.60% DEM James "Jim" Wright 7,568 24.52% 11,723 24.33% 19,291 24.40% Cast Votes: 30,869 96.55% 48,187 96.38% 79,056 97.76% Governor, Vote For 1 REP Rick Perry 16,682 52.94% 24,384 49.45% 41,066 50.81% DEM Chris Bell 4,889 15.52% 6,811 13.81% 11,700 14.48% LIB James Werner 161 0.51% 291 0.59% 452 0.56% IND Carole Keeton Strayhorn 5,506 17.47% 8,280 16.79% 13,786 17.06% IND Richard "Kinky" Friedman 4,262 13.53% 9,543 19.35% 13,805 17.08% James "Patriot" Dillon (W) 10 0.03% 3 0.01% 13 0.02% Cast Votes: 31,510 98.56% 49,312 98.63% 80,822 99.16% Lieutenant Governor, Vote For 1 REP David Dewhurst 22,667 73.38% 35,559 73.53% 58,226 73.47% DEM Maria Luisa Alvarado 6,624 21.44% 10,021 20.72% 16,645 -

Unintended Consequences of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act

The Unintended Consequences of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act The Unintended Consequences of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act Edward Blum The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. To order call toll free 1-800-462-6420 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 or call 1-800-862-5801. NATIONAL RESEARCH NRI INITIATIVE This publication is a project of the National Research Initiative, a program of the American Enterprise Institute that is designed to support, publish, and dissemi- nate research by university-based scholars and other independent researchers who are engaged in the exploration of important public policy issues. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blum, Edward. The unintended consequences of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act / Edward Blum. p. cm. ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-4257-1 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 0-8447-4257-0 1. United States. Voting Rights Act of 1965. 2. African Americans—Suffrage. 3. Minorities—Suffrage—United States—States. 4. Voter registration—United States—States. 5. Election law—United States. 6. Apportionment (Election law)— United States. I. Title. KF4893.B59 2007 342.73'072—dc22 2007036252 11 10 09 08 07 1 2 3 4 5 © 2007 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Wash- ington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or repro- duced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. -

Congresswoman Barbara Jordan Papers, 1936-2011 Collection Overview

Congresswoman Barbara Jordan Papers, 1936-2011 Collection Overview Title: Congresswoman Barbara Jordan Papers, 1936-2011 Predominant Dates:1966-1979 Creator: Barbara C. Jordan (1936-1996) Extent: 600.0 Linear Feet Arrangement: Arranged hierarchically by Series - Box - Folder - Item. Within a series, materials are arranged chronologically then alphabetically. Date Acquired: 01/01/1979. More info below under Accruals. Languages: English Administrative Information Accruals: Additional audio cassette tapes courtesy of Nancy Earl, ca. 1996. Jordan memorial materials, ca. 2000. Related materials for Jordan-related events, 2004-2011. Access Restrictions: Contact Library Special Collections staff at (713) 313-7169 Use Restrictions: All rights reserved by Robert J. Terry Library/Congresswoman Barbara Jordan. Preferred citation: [Identification of item], Congresswoman Barbara C. Jordan Papers, 1936-1996, 1979BJA001, Special Collections, Texas Southern University. Physical Access Note: Robert J. Terry Library, Texas Southern University, 3100 Cleburne Avenue, Houston, TX 77004. First floor. Technical Access Note: Contact Cataloging Department - (713) 313-1074 Acquisition Source: Congresswoman Barbara Jordan transferred physical custody of the collection to Robert J. Terry Library staff in 1979. Related Publications: "Barbara Jordan's America" (television series) Selected Speeches Processing Information: Processed by archives staff. Other Note: Robert J. Terry Library Special Collections page Box and Folder Listing Series I: Texas Senate Series, 1966-1972 This series documents Jordan's activities as a State Senator for the Texas State Legislature, representing District 11. Materials in this series include bills, resolutions, constituent correspondence, internal communications, public relations materials (including newsletters and press releases) and ephemera from Jordan's historic appointment as "Governor for a Day" in 1972. -

MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection MSS 0093 Alfonso Vazquez

Hispanic Archival Collections Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

Cumulative Report — Official

Cumulative Report — Official Fort Bend County, Texas OFFICIAL BALLOT — Special and General Election — November 07, 2006 Page 1 of 17 11/14/2006 11:01 AM Total Number of Voters : 100,526 of 265,320 = 37.89% Precincts Reporting 141 of 141 = 100.00% Party Candidate Early Election Total United States Representative District 22 (Unexpired Term), Vote For 1 REP Steve Stockman 1,984 9.68% 3,141 11.42% 5,125 10.68% REP Giannibicego Hoa Tran 407 1.99% 608 2.21% 1,015 2.11% LIB M. Bob Smither 2,842 13.87% 4,704 17.10% 7,546 15.72% REP Don Richardson 1,076 5.25% 1,760 6.40% 2,836 5.91% REP Shelley Sekula Gibbs 14,182 69.21% 17,295 62.87% 31,477 65.58% Cast Votes: 20,491 71.40% 27,508 66.26% 47,999 68.36% Over Votes: 6 0.02% 0 0.00% 6 0.01% Under Votes: 8,201 28.58% 14,010 33.74% 22,211 31.63% Straight Party, Vote For 1 Republican Party 10,164 54.42% 13,392 43.78% 23,556 47.82% Democratic Party 8,386 44.90% 16,874 55.17% 25,260 51.27% Libertarian Party 127 0.68% 321 1.05% 448 0.91% Cast Votes: 18,677 47.26% 30,587 50.14% 49,264 49.01% Over Votes: 1 0.00% 0 0.00% 1 0.00% Under Votes: 20,842 52.74% 30,419 49.86% 51,261 50.99% United States Senator, Vote For 1 REP Kay Bailey Hutchison 24,611 64.22% 32,919 56.34% 57,530 59.46% DEM Barbara Ann Radnofsky 13,186 34.41% 24,408 41.78% 37,594 38.86% LIB Scott Lanier Jameson 527 1.38% 1,097 1.88% 1,624 1.68% Cast Votes: 38,324 96.97% 58,424 95.77% 96,748 96.24% Over Votes: 0 0.00% 0 0.00% 0 0.00% Under Votes: 1,196 3.03% 2,582 4.23% 3,778 3.76% United States Representative, District 9, Vote For 1 DEM Al Green -

An Assessment of Voting Rights Progress in Texas Prepared for the Project on Fair Representation American Enterprise Institute

An Assessment of Voting Rights Progress in Texas Prepared for the Project on Fair Representation American Enterprise Institute Charles S. Bullock III Richard B. Russell Professor of Political Science Department of Political Science The University of Georgia Athens, GA 30602 Ronald Keith Gaddie Professor of Political Science Department of Political Science The University of Oklahoma Norman, OK 73019 1 An Assessment of Voting Rights Progress in Texas In August 2005, Texas joined California, Hawaii and Mexico to become the fourth state in which most residents were not Anglo. According to Census Bureau estimates, 50.2 percent of the Texas population now belonged to a minority group. When the initial Voting Rights Act was crafted under the watchful eyes of President Lyndon Johnson, Texas was one of four southern states not caught by the trigger mechanism in Section 4. It is hardly surprising that the Texas president would set a threshold that would not bring his home state under the most demanding features of the legislation. The history of the Lone Star state is not free of racial disfranchisement, as University of Houston professor and Texas politics maven Richard Murray points out: In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, blacks became a political force in Texas in counties that had high percentages of slaves. The Twelfth Legislature, elected under a new constitution pushed through by Radical Republicans, included two black senators and nine black representatives. Within a few years, however, white conservative Democrats regained control of Texas politics and began the systematic disenfranchisement of the African-American population, which was completed with the approval of a state poll tax in 1901 and the establishment of a white primary system. -

SUMMARY REPT-GROUP DETAIL General and Special Elections UNOFFICIAL RESULTS November 7, 2006 Dallas County, Texas Run Date:11/14/06 01:35 PM

SUMMARY REPT-GROUP DETAIL General and Special Elections UNOFFICIAL RESULTS November 7, 2006 Dallas County, Texas Run Date:11/14/06 01:35 PM TOTAL VOTES % EV-In Person EV-Mail Election Day Prov EV/ED Elec Day ADA PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 744). 744 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 1197,348 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 409,886 150,138 13,840 245,451 139 318 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 34.23 Straight Party VOTE FOR 1 (WITH 744 OF 744 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Republican Party (REP) . 108,000 46.14 43,554 5,482 58,879 35 50 Democratic Party (DEM) . 124,136 53.04 41,259 4,071 78,620 39 147 Libertarian Party (LIB). 1,913 .82 576 43 1,292 0 2 U. S. Senator VOTE FOR 1 (WITH 744 OF 744 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Kay Bailey Hutchison (REP). 213,215 53.23 81,817 8,175 123,043 74 106 Barbara Ann Radnofsky (DEM) . 179,781 44.88 61,389 5,336 112,818 60 178 Scott Lanier Jameson (LIB). 7,545 1.88 2,366 163 5,006 2 8 U. S. Congressional Dist 3 DISTRICT 03 VOTE FOR 1 (WITH 67 OF 67 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Sam Johnson (REP). 21,793 54.39 7,872 727 13,189 2 3 Dan Dodd (DEM). 17,289 43.15 5,333 418 11,530 2 6 Christopher J. Claytor (LIB) . 989 2.47 276 28 685 0 0 U. S. Congressional Dist 5 DISTRICT 05 VOTE FOR 1 (WITH 110 OF 110 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Jeb Hensarling (REP). 37,378 58.62 13,771 1,534 22,060 7 6 Charlie Thompson (DEM) . -

1. Front Page 1 Layout 1

We’d flip for queermedian Margaret Cho From comedy to music to ‘Dancing with the Stars’ Cho performs this weekend at Verizon Theatre • COMEDY, Page 22 DallasVoice.com DallasVoice.com/Instant-Tea Facebook.com/DallasVoice Twitter.com/DallasVoice The Premier Media Source for LGBT Texas Established 1984 | Volume 27 | Issue 17 FREE | Friday, September 10, 2010 No charges filed Lambert glams Dallas after threats against ensign Dallas man posts ‘Tree of Woe’ photo on Internet with threat to ‘take care of’ Navy ensign fighting anti-gay harassment by superiors JOHN WRIGHT | Online Editor [email protected] Navy Ensign Steve Crowston, the East Texas native who’s made headlines of late with claims of anti-gay harassment by his military superiors, says he learned this week that federal authorities don’t plan to file charges against a Dallas man who made a possible death threat against him on the Internet in August. Crowston, 36, said the Navy Criminal Inves- tigative Service informed him Tuesday, Sept. 7 that federal authorities in Texas don’t plan to pur- sue the case. The unidentified Dallas-based sus- GLITTERATI | Gay pop star Adam Lambert brought his Glam Nation Tour to Dallas on Tuesday, Sept. 8, thrilling the cross-generational crowd of fans that pect reportedly made the threat in response to packed the Palladium Ballroom with a 75 minute set. After the concert, Lambert headed to BJ’s NXS! to continue the party. See more photos of the concert media coverage of Crowston’s harassment allega- and Lambert’s visit to the Oak Lawn bar online at DallasVoice.com/category/photos and DallasVoice.com/category/InstantTea.