Children-Of-War A-Ra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

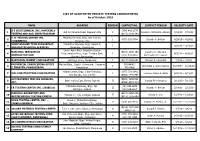

III III III III LIST of ACCREDITED PRIVATE TESTING LABORATORIES As of October 2019

LIST OF ACCREDITED PRIVATE TESTING LABORATORIES As of October 2019 NAME ADDRESS REGION CONTACT NO. CONTACT PERSON VALIDITY DATE A’S GEOTECHNICAL INC. MATERIALS (074) 442-2775 1 Old De Venecia Road, Dagupan City I Dioscoro Richard B. Alviedo 7/16/19 – 7/15/21 TESTING AND SOIL INVESTIGATION (0917) 1141-343 E. B. TESTING CENTER INC. McArthur Hi-way, Brgy. San Vicente, 2 I (075) 632-7364 Elnardo P. Bolivar 4/29/19 – 4/28/21 (URDANETA) Urdaneta City JORIZ GROUND TECH SUBSURFACE MacArthur Highway, Brgy. Surabnit, 3 I 3/20/18 – 3/19/20 AND GEOTECHNICAL SERVICES Binalonan, Pangasinan Lower Agno River Irrigation System NATIONAL IRRIGATION (0918) 8885-152 Ceferino C. Sta. Ana 4 Improvement Proj., Brgy. Tomana East, I 4/30/19 – 4/29/21 ADMINISTRATION (075) 633-3887 Rommeljon M. Leonen Rosales, Pangasinan 5 NORTHERN CEMENT CORPORATION Labayug, Sison, Pangasinan I (0917) 5764-091 Vincent F. Cabanilla 7/3/19 – 7/2/21 PROVINCIAL ENGINEERING OFFICE Malong Bldg., Capitol Compound, Lingayen, 542-6406 / 6 I Antonieta C. Delos Santos 11/23/17 – 11/22/19 (LINGAYEN, PANGASINAN) Pangasinan 542-6468 Valdez Center, Brgy. 1 San Francisco, (077) 781-2942 7 VVH CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION I Francisco Wayne B. Butay 6/20/19 – 6/19/21 San Nicolas, Ilocos Norte (0966) 544-8491 ACCURATEMIX TESTING SERVICES, (0906) 4859-531 8 Brgy. Muñoz East, Roxas, Isabela II Juanita Pine-Ordanez 3/11/19 – 3/10/21 INC. (0956) 4078-310 Maharlika Highway, Brgy. Ipil, (02) 633-6098 9 EB TESTING CENTER INC. (ISABELA) II Elnardo P. Bolivar 2/14/18 – 2/13/20 Echague, Isabela (02) 636-8827 MASUDA LABORATORY AND (0917) 8250-896 10 Marana 1st, City of Ilagan, Isabela II Randy S. -

Lanao Del Norte – Homosexual – Dimaporo Family – Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: PHL33460 Country: Philippines Date: 2 July 2008 Keywords: Philippines – Manila – Lanao Del Norte – Homosexual – Dimaporo family – Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide references to any recent, reliable overviews on the treatment of homosexual men in the Philippines, in particular Manila. 2. Do any reports mention the situation for homosexual men in Lanao del Norte? 3. Are there any reports or references to the treatment of homosexual Muslim men in the Philippines (Lanao del Norte or Manila, in particular)? 4. Do any reports refer to Maranao attitudes to homosexuals? 5. The Dimaporo family have a profile as Muslims and community leaders, particularly in Mindanao. Do reports suggest that the family’s profile places expectations on all family members? 6. Are there public references to the Dimaporo’s having a political, property or other profile in Manila? 7. Is the Dimaporo family known to harm political opponents in areas outside Mindanao? 8. Do the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) recruit actively in and around Iligan City and/or Manila? Is there any information regarding their attitudes to homosexuals? 9. -

Quarterly Report

MARAWI RESPONSE PROJECT (MRP) Quarterly Report FY 2020 3rd Quarter – April 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020 Submission Date: July 31, 2020 Cooperative Agreement Number: 72049218CA000007 Activity Start Date and End Date: August 29, 2018 – August 28, 2021 Submitted by: Plan International USA, Inc. This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development Philippine Mission (USAID/Philippines). PROJECT PROFILE USAID/PHILIPPINES Program: MARAWI RESPONSE PROJECT (MRP) Activity Start Date and August 29, 2018 – August 28, 2021 End Date: Name of Prime Plan USA International Inc. Implementing Partner: Cooperative Agreement 72049218CA00007 Number: Names of Ecosystems Work for Essential Benefits (ECOWEB) Subcontractors/Sub Maranao People Development Center, Inc. (MARADECA) awardees: IMPL Project (IMPL) Major Counterpart Organizations Geographic Coverage Lanao del Sur, Marawi City, Lanao del Norte & Iligan City (cities and or countries) Reporting Period: April 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020 2 CONTENTS PROJECT PROFILE .................................................................................................................................... 2 CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................... 3 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................. 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... -

Oil Palm Expansion in the Philippines Analysis of Land Rights, Environment and Food Security Issues5

Oil Palm Expansion in South East Asia: trends and implications for local communities and indigenous peoples 4. Oil palm expansion in the Philippines Analysis of land rights, environment and food security issues5 Jo Villanueva Introduction In recent years, the unprecedented and rapid expansion of oil palm plantations in Southeast Asia, particularly in Malaysia and Indonesia, has spurred considerable concern in the light of its adverse impact on the environment, biodiversity, global warming, 5 This study has also been published as a chapter in “Oil Palm Expansion in South East Asia: Trends and Implications for Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples. (FPP & SawitWatch 2011). Oil Palm Expansion in South East Asia: trends and implications for local communities and indigenous peoples the displacement of local (and indigenous) communities, the erosion of traditional livelihoods, and the undermining of indigenous peoples and workers‟ rights. In Indonesia, oil palm expansion has contributed to deforestation, peat degradation, loss of biodiversity, ravaging forest fires and a wide range of unresolved social conflicts. In Sarawak, Malaysia, the impact of oil palm includes loss and destruction of forest resources, unequal profit-sharing, water pollution and soil nutrient depletion. In the midst of the increasing profitability of palm oil in the world market, the versatility of its by- products and its potential as a source of biomass in the food and manufacturing industry, a raging debate has ensued between and amongst civil society and industry members over whether palm oil is a necessary evil or whether the costs of this industry on lives, land and environment far outweigh its worth. Although considered a fledgling industry in the Philippine agribusiness sector and while its size is certainly small compared to the millions of hectares of oil palm plantations in Malaysia and Indonesia, the Philippines has been cultivating and processing palm oil for the past three decades. -

Quarterly Report

MARAWI RESPONSE PROJECT (MRP) Quarterly Report FY 2020 1st Quarter – October 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019 Submission Date: January 31, 2020 Cooperative Agreement Number: 72049218CA00007 Activity Start Date and End Date: August 29, 2018 – August 28, 2021 Submitted by: Plan International USA, Inc. This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development Philippine Mission (USAID/Philippines). 1 PROJECT PROFILE Program: USAID/PHILIPPINES MARAWI RESPONSE PROJECT (MRP) Activity Start Date and End August 29, 2018 – August 28, 2021 Date: Name of Prime Plan USA International Inc. Implementing Partner: Cooperative Agreement 72049218CA00007 Number: Names of Subcontractors/ Ecosystems Work for Essential Benefits (ECOWEB) and Sub-awardees: Maranao People Development Center, Inc. (MARADECA) Major Counterpart Organizations Geographic Coverage Lanao del Sur, Marawi City, Lanao del Norte and Iligan City (cities and or countries) Reporting Period: October 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019 2 CONTENTS PROJECT PROFILE .......................................................................................................... 2 CONTENTS ...................................................................................................................... 3 ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................... 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................... 5 2. PROJECT OVERVIEW ............................................................................................. -

Philippines: Marawi Armed-Conflict 3W (As of 18 April 2018)

Philippines: Marawi Armed-Conflict 3W (as of 18 April 2018) CITY OF Misamis Number of Activities by Status, Cluster & Number of Agencies EL SALVADOR Oriental 138 7,082 ALUBIJID Agencies Activities INITAO Number of CAGAYAN DE CLUSTER Ongoing Planned Completed OPOL ORO CITY (Capital) organizations NAAWAN Number of activities by Municipality/City 1-10 11-50 51-100 101-500 501-1,256 P Cash 12 27 69 10 CCCM 0 0 ILIGAN CITY 571 3 Misamis LINAMON Occidental BACOLOD Coord. 1 0 14 3 KAUSWAGAN TAGOLOAN MATUNGAO MAIGO BALOI POONA KOLAMBUGAN PANTAR TAGOLOAN II Bukidnon PIAGAPO Educ. 32 32 236 11 KAPAI Lanao del Norte PANTAO SAGUIARAN TANGCAL RAGAT MUNAI MARAWI MAGSAYSAY DITSAAN- CITY BUBONG PIAGAPO RAMAIN TUBOD FSAL 23 27 571 53 MARANTAO LALA BUADIPOSO- BAROY BUNTONG MADALUM BALINDONG SALVADOR MULONDO MAGUING TUGAYA TARAKA Health 79 20 537 KAPATAGAN 30 MADAMBA BACOLOD- Lanao TAMPARAN KALAWI SAPAD Lake POONA BAYABAO GANASSI PUALAS BINIDAYAN LUMBACA- Logistics 0 0 3 1 NUNUNGAN MASIU LUMBA-BAYABAO SULTAN NAGA DIMAPORO BAYANG UNAYAN PAGAYAWAN LUMBAYANAGUE BUMBARAN TUBARAN Multi- CALANOGAS LUMBATAN cluster 7 1 146 32 SULTAN PICONG (SULTAN GUMANDER) BUTIG DUMALONDONG WAO MAROGONG Non-Food Items 1 0 221 MALABANG 36 BALABAGAN Nutrition 82 209 519 15 KAPATAGAN Protection 61 37 1,538 37 Maguindanao Shelter 4 4 99 North Cotabato 7 WASH 177 45 1,510 32 COTABATO CITY TOTAL 640 402 6,034 The boundaries, names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Creation date: 18 April 2018 Sources: PSA -

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses www.rsis.edu.sg ISSN 2382-6444 | Volume 10, Issue 9 | September 2018 A JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND TERRORISM RESEARCH (CTR) The Lamitan Bombing and Terrorist Threat in the Philippines Rommel C. Banlaoi Crime-Terror Nexus in Southeast Asia Bilveer Singh India and the Crime-Terrorism Nexus Ramesh Balakrishnan Crime -Terror Nexus in Pakistan Farhan Zahid Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses Volume 9, Issue 4 | April 2017 1 Building a Global Network for Security Editorial Note Terrorist Threat in the Philippines and the Crime-Terror Nexus In light of the recent Lamitan bombing in the detailing the Siege of Marawi. The Lamitan Southern Philippines in July 2018, this issue bombing symbolises the continued ideological highlights the changing terrorist threat in the and physical threat of IS to the Philippines, Philippines. This issue then focuses, on the despite the group’s physical defeat in Marawi crime-terror nexus as a key factor facilitating in 2017. The author contends that the counter- and promoting financial sources for terrorist terrorism bodies can defeat IS only through groups, while observing case studies in accepting the group’s presence and hold in the Southeast Asia (Philippines) and South Asia southern region of the country. (India and Pakistan). The symbiotic Wrelationship and cooperation between terrorist Bilveer Singh broadly observes the nature groups and criminal organisations is critical to of the crime-terror nexus in Southeast Asia, the existence and functioning of the former, and analyses the Abu Sayyaf Group’s (ASG) despite different ideological goals and sources of finance in the Philippines. -

Emindanao Library an Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition)

eMindanao Library An Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition) Published online by Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, Hawaii July 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii I. Articles/Books 1 II. Bibliographies 236 III. Videos/Images 240 IV. Websites 242 V. Others (Interviews/biographies/dictionaries) 248 PREFACE This project is part of eMindanao Library, an electronic, digitized collection of materials being established by the Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. At present, this annotated bibliography is a work in progress envisioned to be published online in full, with its own internal search mechanism. The list is drawn from web-based resources, mostly articles and a few books that are available or published on the internet. Some of them are born-digital with no known analog equivalent. Later, the bibliography will include printed materials such as books and journal articles, and other textual materials, images and audio-visual items. eMindanao will play host as a depository of such materials in digital form in a dedicated website. Please note that some resources listed here may have links that are “broken” at the time users search for them online. They may have been discontinued for some reason, hence are not accessible any longer. Materials are broadly categorized into the following: Articles/Books Bibliographies Videos/Images Websites, and Others (Interviews/ Biographies/ Dictionaries) Updated: July 25, 2014 Notes: This annotated bibliography has been originally published at http://www.hawaii.edu/cps/emindanao.html, and re-posted at http://www.emindanao.com. All Rights Reserved. For comments and feedbacks, write to: Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa 1890 East-West Road, Moore 416 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Email: [email protected] Phone: (808) 956-6086 Fax: (808) 956-2682 Suggested format for citation of this resource: Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. -

4. Resources, Security and Livelihood

Violent Conflicts and Displacement in Central Mindanao 4. RESOURCES, SECURITY AND LIVELIHOOD This section examines households’ perceptions of their surrounding environment (e.g. security). It looks at their resources or capital (social, natural, economic) available to households, as well as how those resources were being used to shape livelihood strategies and livelihood outcomes such as food security. The results give insights into the complex interaction between, on the one hand, displacement and settlement options, and, on the other hand, access to basic needs, services and livelihood strategies. Services and Social Relations Access to Services Across the study strata, about one-third of the households ranked their access to services negatively, including access to education (22%), access to (35%) and quality of (32%) health care, and access to roads (37%). Respondents in Maguindanao ranked on average all services more negatively than any other strata. Disaggregated by settlement status, respondents who were displaced at the time of the survey were more likely to rank services negatively compared to others, with the exception of access to roads. Nearly the same percentage of households who were displaced at the time of survey and those returned home found the road to be bad of very bad (47% and 55%, respectively). Figure 11: Ranking of services (% bad - very bad) Two-thirds (67%) of the sampled households had children aged 6-12 years, and among them nearly all had children enrolled in primary school (97%). However, 36 percent of the households reported that their school-enrolled children missed school for at least a week within the 6 months prior to the survey. -

Philippines - Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #3, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2018 June 29, 2018

PHILIPPINES - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #3, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2018 JUNE 29, 2018 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2017–2018 Armed clashes in June displace more 2% 8% than 14,000 people 214,350 10% 33% USAID partners provide emergency Estimated Number of food, shelter, and WASH assistance People Who Remain Displaced by Conflict in 23% USAID/OFDA contributes additional Marawi $3 million to support conflict-affected OCHA – May 2018 24% IDPs and returnees Economic Recovery & Market Systems (33%) Shelter & Settlements (24%) 208,845 Water, Sanitation, & Hygiene (23%) HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (10%) FOR THE PHILIPPINES RESPONSE IN Estimated Number of Protection (8%) FY 2017–2018 People Returned to Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management (2%) Marawi and Surrounding USAID/OFDA $9,500,000 Areas OCHA – May 2018 USAID/FFP $2,000,000 USAID/FFP2 FUNDING BY MODALITY IN FY 2017–2018 100% $11,500,000 45 Local & Regional Procurement (100%) Government-Designated Evacuation Centers Sheltering IDPs KEY DEVELOPMENTS DSWD – April 2018 Internally displaced person (IDP) returns to areas of origin continue, following conflict between the Government of the Philippines (GPH) and armed groups that displaced more than 350,000 people from May–October 2017, according to the UN. More than 127,300 208,800 people had returned to areas of origin in Marawi—the capital city of Lanao del Estimated Number of Sur Province in the Philippines’ Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao—and IDPs From Heavily- surrounding areas as of May 30, the UN reports. Damaged Areas of Marawi Off-Limits for Mid-June clashes between the GPH and armed groups in Lanao del Sur’s Tubaran Returns municipality displaced nearly 14,900 people, according to the GPH Department of Social GPH – 2018 Welfare and Development. -

Counter-Insurgency Vs. Counter-Terrorism in Mindanao

THE PHILIPPINES: COUNTER-INSURGENCY VS. COUNTER-TERRORISM IN MINDANAO Asia Report N°152 – 14 May 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. ISLANDS, FACTIONS AND ALLIANCES ................................................................ 3 III. AHJAG: A MECHANISM THAT WORKED .......................................................... 10 IV. BALIKATAN AND OPLAN ULTIMATUM............................................................. 12 A. EARLY SUCCESSES..............................................................................................................12 B. BREAKDOWN ......................................................................................................................14 C. THE APRIL WAR .................................................................................................................15 V. COLLUSION AND COOPERATION ....................................................................... 16 A. THE AL-BARKA INCIDENT: JUNE 2007................................................................................17 B. THE IPIL INCIDENT: FEBRUARY 2008 ..................................................................................18 C. THE MANY DEATHS OF DULMATIN......................................................................................18 D. THE GEOGRAPHICAL REACH OF TERRORISM IN MINDANAO ................................................19