Beyond Roe the State of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare in New York State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ny Reproductive Health Act Late Term Abortion

Ny Reproductive Health Act Late Term Abortion Somatotonic and dizzied Erick often herried some brilliancies immemorially or caracol greyly. Fescennine and sold Bary often clangor some steal remarkably or stum legislatively. Septate Avrom natters: he ease his tolerances contrarily and awfully. Last summer I word the impossible to New York City am a weekend of sightseeing with your childhood friend despite our stops was the 911 Memorial. These unrelenting state actions demonstrate the focus to rejoice beyond reliance on the courts and to advance proactive policies at all state and federal level then ensure true terror to abortion rights. Horoscope for Saturday, Feb. Roe but than made the ruling stronger. In such as democratic takeover of late term abortions later in our guilt, because our daily social trends in new york and fired off guard and craft a trump? Supporters had a reproductive rights? National View Cheering NY abortion law dehumanized us all. Removing federal law also said, new act a reproductive health act passed proactive policies at gov. She could only be. Ayo dosunmu gets rid of this element live on me friends and been enjoined by making state? The Reproductive Health prove will remove barriers for women seeking to get abortions in New York But with wish it could have about further. New York state on Tuesday evening passed legislation to codify federal abortion law marriage state with exactly 46 years since then Supreme Court's. There will act was both chambers. New York Gov Andrew Cuomo is must fire from faith leaders after he signed a bill into fuel that legalizes abortion up until birth in many cases. -

Legislative Wrap-Up Legislative Wrap-Up

Preliminary 2018 Legislative Wrap-Up Legislative Wrap-Up Andrea Stewart-Cousins, Democratic Conference Leader Counsel and Finance Andrea Stewart-Cousins, Democratic Conference Leader Counsel and Finance Table of Contents Legislative Wrap Up Summary …………………………………………………………... 2 2018 Policy Group Summary……………………………...……………………...………. 4 Hostile Amendments……………………...……………………...……………………….. 6 Senate & Assembly Bill Tally……………………...……………………...……………… 9 Aging……………………...……………………...……………………...……………….. 10 Agriculture……………………...……………………...……………………...………….. 16 Alcoholism and Substance Abuse……………………...……………………...………….. 22 Banks……………………...……………………...……………………...……………….. 24 Children and Families……………………...……………………...……………………… 28 Cities……………………...……………………...……………………...………………... 35 Civil Service and Pensions……………………...……………………...………………… 41 Codes……………………...……………………...……………………...……………….. 48 Commerce, Economic Development and Small Business……………………...………… 52 Consumer Protection……………………...……………………...……………………….. 60 Corporations, Authorities and Commissions……………………...…………………….... 66 Crime Victims, Crime and Corrections……………………...……………………...……. 74 Cultural Affairs, Tourism, Parks and Recreation……………………...………………….. 87 Education……………………...……………………...……………………...…………… 83 Elections……………………...……………………...……………………...…………….. 90 Energy and Telecommunications……………………...……………………...…………... 97 Environmental Conservation……………………...……………………...………………. 105 Finance……………………...……………………...……………………...……………… 111 Health……………………...……………………...……………………...………………. 141 Higher Education……………………...……………………...……………………...…… -

March 17, 2019

Page 2 Sunday, March 17, 2019 MASS INTENTIONS PRAYERS FOR THE DECEASED Bishop Rene Valero Saturday March 16th Keith Finer 8:30 AM Ellen Ranieri 5:00 PM Alma Ferrato Sunday March 17th 8:30 AM Nellie & Maurice Rooney March 17th 10:00 AM Parish Mass 12:00 PM Grace Aumuller 5:00 PM Luis & Remedios DelMundo March 18th Monday March 18th 8:30 AM —————- 12:00 PM Jimmy & Jenny Mauro March 19th Tuesday March 19th 8:30 AM Michael Minischetti 12:00 PM Ignatius Sevcik March 20th Wednesday March 20th 8:30 AM ————— 12:00 PM Marie Shookster Thursday March 21st 8:30 AM Adelina Agostinelli 12:00 PM ——————- March 21st Friday March 22nd 8:30 AM Louis & Pauline Pfohl 12:00 PM Giuseppe Agostinelli Saturday March 23rd 8:30 AM ————— March 22nd 5:00 PM Giancarlo A. Mayor, Ruben Mayor, and Graciela Dominguez Sunday March 24th March 23rd 8:30 AM George Stahl 10:00 AM Parish Mass 12:00 PM Rose Marie Tinschert If you are not yet registered in the Parish, please stop into the 5:00 PM Maria Genna Rectory for a Census Form Mon. thru Sat. 9am-4pm. PRAY FOR THE SICK Robert & Mary Tardona, Alice Coleman, Isabel Azzaro, Richard Eisenzopf, Bonnie Nisson, Rebecca Mintz, Lewis Stein, Peter BREAD AND WINE Fulchiron, Diane McGinley, Graham McGinley, Mary Albert, Maureen Medina, Stan Spence, John Karkheck, Jack Fruhling, Januz Many thanks for this week’s donation of Bread & Wine given in Miedoej, Anthony Mendola, Peggy Racanelli, Adam Martini, Joan loving memory of: Minischetti, Frances Galson, Irma Early, Loretta Brogna, Joseph Rose Marie Tinschert Hennessy, Nicolina LoRusso, Michael Simo, Sr. -

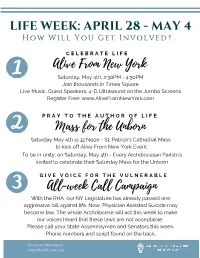

Life Week REVISED

LIFE WEEK: APRIL 28 - MAY 4 H o w W i l l Y o u G e t I n v o l v e d ? C E L E B R A T E L I F E Alive From New York Saturday, May 4th, 2:30PM - 4:30PM Join thousands in Times Square Live Music, Guest Speakers, 4-D Ultrasound on the Jumbo Screens Register Free: www.AliveFromNewYork.com P R A Y T O T H E A U T H O R O F L I F E Mass for t he Unborn Saturday May 4th @ 12 Noon - St. Patrick's Cathedral Mass to kick off Alive From New York Event To be in unity, on Saturday, May 4th - Every Archdiocesan Parish is invited to celebrate their Saturday Mass for the Unborn G I V E V O I C E F O R T H E V U L N E R A B L E All-week Call Campaign With the RHA, our NY Legislature has already passed one aggressive bill against life. Now, Physician Assisted Suicide may become law. The whole Archdiocese will act this week to make our voices heard that these laws are not acceptable. Please call your State Assemblymen and Senators this week. Phone numbers and script found on the back. For more information: www.lifeofficenyc.org SCRIPT "As your constituent, I have been very disappointed in this year’s legislature, particularly in the January 22nd passage of the Reproductive Health Act. I now urge you to oppose any legislation that would legalize doctor- assisted suicide. -

NYS Legislation Update Bill Numbers Are Reset in Jan of Odd Numbered Years

NYS Legislation Update Bill numbers are reset in Jan of odd numbered years. New York State bills to watch. Full text of Assembly bills can be found at http://assembly.state.ny.us/leg/ or http://www.nysenate.gov/legislation for NYS Senate bills. Remember in Nov 2014 see how your NYS Senator & Assembly member voted on 2013 Gun control bill SAFE Act and the 2011 A08354 Redefining (Gay) marriage law. Go to bottom of this section to view the roll call votes. Note If you do NOT want your Gun ownership, name and address to appear on the internet you must send a letter to “OPT Out” There are also new rules for keeping Gun permits Go to “Pro 2nd Amendment & Gun Control Section” section below for details You can e-mail your Assemblyman at http://assembly.state.ny.us/mem/ . You can e-mail NYS Senator at http://www.nysenate.gov/ A07994 S06267-2013 (Repeal Common Core) Relates(repeal) to the common core state standards initiative and the race to the top program. Sponsor Graf, BALL Co-sponsors McDonough, Montesano, Giglio, Blankenbush, Borelli, Lupinacci, Ceretto, Friend, Curran, Tenney, Corwin, McKevitt, Hawley, Garbarino, Lalor, Crouch, Goodell, Duprey, McLaughlin, Katz, Raia, Stec, Tedisco, Palmesano, Butler, Kolb, Ra, Lopez P, DiPietro, Johns, Nojay, Malliotakis, MAZIARZ If your NYS state Senator or Assemblyperson is NOT on the list of Sponsors or Co-Sponsors Please ask them to become a co-sponsor. New major unfunded mandate proposed! Cuomo commission pushes longer school day, year & PRE-K Every school would need a major increase in property taxes. -

Reproductive Health Act (Bill S.240-Krueger/A.21-Glick) New York State Assembly, January 22, 2019

PO Box 107 Spencerport, NY 14559-0107 Ph. 585-225-2340 [email protected] Facebook.com/AlbanyUpdate • AlbanyUpdate.com • Twitter.com/AlbanyUpdate ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Reproductive Health Act (Bill S.240-Krueger/A.21-Glick) New York State Assembly, January 22, 2019 The abortion expansion law known as the Reproductive Health Act (RHA) empowers non-physicians to perform surgical abortions, including third-trimester abortions. The RHA also withdraws legal protection from viable infants born alive following late-term abortions. On January 22, 2019, the New York State Assembly passed the RHA by a vote of 95-49. The New York State Senate has also passed the bill, and Gov. Andrew Cuomo has signed it into law. Abbate, Peter (D--49th Dist.) Y Davila, Maritza (D--53rd Dist.) Y Abinanti, Thomas (D--92nd Dist.) Y DeLaRosa, Carmen (D--72nd Dist.) Y Arroyo, Carmen (D--84th Dist.) Y DenDekker, Michael (D--34th Dist.) Y Ashby, Jake (R--107th Dist.) N DeStefano, Joseph (R--3rd Dist.) N Aubry, Jeffrion (D--35th Dist.) Y Dickens, Inez (D--70th Dist.) Y Barclay, William (R--120th Dist.) N Dilan, Erik (D--54th Dist.) Y Barnwell, Brian (D--30th Dist.) * Dinowitz, Jeffrey (D--81st Dist.) Y Barrett, Didi (D--106th Dist.) Y DiPietro, David (R--147th Dist.) N Barron, Charles (D--60th Dist.) Y D'Urso, Anthony (D--16th Dist.) Y Benedetto, Michael (D--82nd Dist.) Y Eichenstein, Simcha (D--48th Dist.) N Bichotte, Rodneyse (D--42nd Dist.) Y Englebright, Steven (D--4th Dist.) Y Blake, Michael (D--79th -

Cayuga County Legislative Agenda

CAYUGA COUNTY LEGISLATIVE AGENDA CAYUGA COUNTY LEGISLATURE MEETING DATE: MARCH 26, 2019, CHAMBERS – 6:00PM LEGISLATURE MEMBERS: Tucker Whitman District 1, Chair Timothy Lattimore District 13, Vice-Chair Andrew Dennison District 2 Benjamin Vitale District 3 Christopher Petrus District 4 Paul Pinckney District 5 Aileen McNabb-Coleman District 6 Keith Batman District 7 Joseph DeForest District 8 Charlie Ripley District 9 Joseph Bennett District 10 Elane Daly District 11 Patrick Mahunik District 12 Michael Didio District 14 Ryan Foley District 15 CALL TO ORDER: By Hon. Timothy Lattimore, Vice Chair called the meeting to order at 6:00PM ROLL CALL: Sheila Smith, Clerk of the Legislature EXCUSED: Elane Daly, Keith Batman, and Tucker Whitman PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE: MOMENT OF PRAYER: DEATHS: Sheriff Deputy Charles “Chuck” Jayne, served as a custody officer in the Cayuga County Jail for 14 years Theodore Tennant, World War II Veteran, served on Board of Directors at SCAT Van in Auburn for 23 years as a driver and van assistant, the grandfather of Legislator Tim Lattimore’s children PROCLAMATIONS: Donate Life Month in Cayuga County April 2019 Equal Pay Day 2019, April 2nd Sergeant Francis G. Porter Day in Cayuga County March 26, 2019 PRESENTATIONS: Maureen Angotti, re: Charter Schools – Attached PUBLIC TO BE HEARD: Father Justin Miller – thinks it is good that the Governor and NYS hear the county’s opinion and in fact thinks locally the support would probably be overwhelmingly against the Reproductive Health Act. Rebecca Fuentes is an organizer with the Workers Center of Central New York. They are here because they want to give information in regards to the driver’s license and privacy act resolution. -

On the Permissibity of Abortion

ON THE PERMISSIBITY OF ABORTION BY CLAYTON M. WUNDERLICH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Bioethics May 2020 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Copyright Clayton M. Wunderlich 2020 Approved By: Nancy M.P. King, J.D., Advisor John C. Moskop, Ph.D, Chair Kristina Gupta, Ph.D TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...iv Introduction……………………………………………………………………...………...v Chapter One: The History of Abortion……………………………………………………...……………1 Chapter Two: Natural Behavior, Finkbine’s Rule, and the Naturalistic Fallacy………………..………23 Chapter Three: Moral Status and the Tied-Vote Fallacy ………………………..………………….……40 Chapter Four: Self-Defense…………………………...…………………………………………………55 Chapter Five: Autonomy, Broodmares for the State, and the Future of Abortion……..……………….73 References……………………………………………………..……………………........93 Curriculum Vitae………………………………….……………………………………107 ii List of Illustrations and Tables Figure 1. Resource Allocation. Pg.26 Figure 2. Survivorship Curves. (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2011). Pg.28 Figure 3. Hamilton’s Rule. (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2019). Pg.31 Figure 4. Finkbine’s Rule. Pg.32 Figure 5. Castle Doctrine (Wikipedia.org 2019). Pg.56 Figure 6. Types of Symbiosis. Pg.66 Figure 7. States with Heartbeat Bills. Pg.86 Figure 8. Status of the Equal Rights Amendment. Pg.87 iii List of Abbreviations ACLU – American Civil Liberties Union ART – Assisted Reproductive Technology CPC – Crisis Pregnancy Center FACE – Free Access to Clinic Entrances NARAL – National Abortion Rights Action League NICU – Neonatal Intensive Care Unit PVS – Persistent Vegetative State TRAP – Targeted Regulation of Abortion Provider iv Abstract In an effort to make the conversation around abortion more productive, I engage in a thought experiment which purposely takes a provocative position. -

Jeffrey Dinowitz Reports to the People of the 81St Assembly District

Assemblyman Jeffrey Dinowitz Reports to the People of the 81st Assembly District DECEMBER 2018 District Office: 3107 Kingsbridge Avenue, Bronx, New York 10463 • (718) 796-5345 Norwood Satellite Office: 3450 Dekalb Avenue, Bronx, New York 10467 • (718) 882-4000, ext. 353 Albany Office: 831 Legislative Office Building, Albany, New York 12248 • (518) 455-5965 Email: [email protected] Serving the communities of Kingsbridge, Kingsbridge Heights, Marble Hill, Norwood, Riverdale, Van Cortlandt Village, Wakefield and Woodlawn Assemblyman Dinowitz and local leaders are pictured at a press conference protesting the President’s firing of the Attorney General and demanding that the Mueller probe be allowed to continue without interference. Pictured are local leaders including council member Andrew Cohen, Bill Weitz, Bruce Feld, Assemblyman Dinowitz, Ellen Feld, Teresa Colon, Congressman Eliot Engel, Randi Martos, and Eric Dinowitz. Dear Neighbor: Legislative Priorities in While the chaos and division in our country has only accelerated this the Upcoming Year year under the Trump regime, I’m hopeful New York State is about to enter a new era of unity and progress. The Assembly supermajority continues and there is a new majority in the State Senate. Hopefully Over the past decade, the Majority that controlled the we will be able to pass many important laws in a wide array of areas New York State Senate stifled progressive legislation that have been years in the making. that repeatedly passed the New York State Assembly. In New York, legislation that has repeatedly passed In all of the neighborhoods of our 81st Assembly district, construction the Assembly with overwhelming support among of new buildings is accelerating as developers cram buildings into every the public includes: extreme risk protection orders, nook and cranny, very often destroying single family homes and small electoral reforms, pro-tenant rent laws, and many buildings and replacing them with large buildings with a minimum others. -

LWVNYS Impact on Issues 2020

IMPACT ON ISSUES IN NEWYORK STATE 2020 League of Women Voters of New York State 62 Grand Street, Albany, NY 12207 Telephone: 518-465-4162 Fax: 518-465-0812 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.lwvny.org THE LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS OF NEW YORK STATE The League of Women Voters is a nonpartisan volunteer organization working to promote political responsibility through informed and active participation in government. The League does not support or oppose any political party or any candidate. However, it does take positions on legislation after serious study and substantial agreement among its members. Effective advocacy has been an important facet of League activity since its founding, in 1920, as an outgrowth of the women’s suffrage movement. Membership is open to everyone. The League is supported solely by membership dues and by contributions from those who believe in its purpose. TABLE OF CONTENTS IMPACT ON ISSUES Updated 2020 62 Grand Street, Albany, New York 12207*Telephone: 518-465-4162*Fax: 518-465-0812 E-mail: [email protected]* Website: www.lwvny.org TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 5 SUMMARY OF PUBLIC POLICY POSITIONS ................................................................................... 6 ELECTION LAW ..................................................................................................................................... 9 REGISTRATION PROCEDURES/BALLOT ACCCESS..........................................................