Gαi-Mediated TRPC4 Activation by Polycystin-1 Contributes To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRPC1 Regulates the Activity of a Voltage-Dependent Nonselective Cation Current in Hippocampal CA1 Neurons

cells Article TRPC1 Regulates the Activity of a Voltage-Dependent Nonselective Cation Current in Hippocampal CA1 Neurons 1, 1 1,2 1,3, Frauke Kepura y, Eva Braun , Alexander Dietrich and Tim D. Plant * 1 Pharmakologisches Institut, BPC-Marburg, Fachbereich Medizin, Philipps-Universität Marburg, Karl-von-Frisch-Straße 2, 35043 Marburg, Germany; [email protected] (F.K.); braune@staff.uni-marburg.de (E.B.); [email protected] (A.D.) 2 Walther-Straub-Institut für Pharmakologie und Toxikologie, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, 80336 München, Germany 3 Center for Mind, Brain and Behavior, Philipps-Universität Marburg, 35032 Marburg, Germany * Correspondence: plant@staff.uni-marburg.de; Tel.: +49-6421-28-65038 Present address: Institut für Bodenkunde und Pflanzenernährung/Institut für angewandte Ökologie, y Hochschule Geisenheim University, Von-Lade-Str. 1, 65366 Geisenheim, Germany. Received: 27 November 2019; Accepted: 14 February 2020; Published: 18 February 2020 Abstract: The cation channel subunit TRPC1 is strongly expressed in central neurons including neurons in the CA1 region of the hippocampus where it forms complexes with TRPC4 and TRPC5. To investigate the functional role of TRPC1 in these neurons and in channel function, we compared current responses to group I metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR I) activation and looked +/+ / for major differences in dendritic morphology in neurons from TRPC1 and TRPC1− − mice. mGluR I stimulation resulted in the activation of a voltage-dependent nonselective cation current in both genotypes. Deletion of TRPC1 resulted in a modification of the shape of the current-voltage relationship, leading to an inward current increase. In current clamp recordings, the percentage of neurons that responded to depolarization in the presence of an mGluR I agonist with a plateau / potential was increased in TRPC1− − mice. -

Structure of the Mouse TRPC4 Ion Channel 1 2 Jingjing

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/282715; this version posted March 15, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Structure of the mouse TRPC4 ion channel 2 3 Jingjing Duan1,2*, Jian Li1,3*, Bo Zeng4*, Gui-Lan Chen4, Xiaogang Peng5, Yixing Zhang1, 4 Jianbin Wang1, David E. Clapham2, Zongli Li6#, Jin Zhang1# 5 6 7 1School of Basic Medical Sciences, Nanchang University, Nanchang, Jiangxi, 330031, China. 8 2Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Janelia Research Campus, Ashburn, VA 20147, USA 9 3Department of Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 10 40536, USA. 11 4Key Laboratory of Medical Electrophysiology, Ministry of Education, and Institute of 12 Cardiovascular Research, Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, Sichuan, 646000, China 13 5The Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang 14 University, Nanchang 330006, China. 15 6Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Biological Chemistry and Molecular 16 Pharmacology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA. 17 18 *These authors contributed equally to this work. 19 # Corresponding authors bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/282715; this version posted March 15, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 20 Abstract 21 Members of the transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channels conduct cations into cells. They 22 mediate functions ranging from neuronally-mediated hot and cold sensation to intracellular 23 organellar and primary ciliary signaling. -

TRPM8 Channels and Dry Eye

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title TRPM8 Channels and Dry Eye. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2gz2d8s3 Journal Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 11(4) ISSN 1424-8247 Authors Yang, Jee Myung Wei, Edward T Kim, Seong Jin et al. Publication Date 2018-11-15 DOI 10.3390/ph11040125 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California pharmaceuticals Review TRPM8 Channels and Dry Eye Jee Myung Yang 1,2 , Edward T. Wei 3, Seong Jin Kim 4 and Kyung Chul Yoon 1,* 1 Department of Ophthalmology, Chonnam National University Medical School and Hospital, Gwangju 61469, Korea; [email protected] 2 Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon 34141, Korea 3 School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Dermatology, Chonnam National University Medical School and Hospital, Gwangju 61469, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 September 2018; Accepted: 12 November 2018; Published: 15 November 2018 Abstract: Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels transduce signals of chemical irritation and temperature change from the ocular surface to the brain. Dry eye disease (DED) is a multifactorial disorder wherein the eyes react to trivial stimuli with abnormal sensations, such as dryness, blurring, presence of foreign body, discomfort, irritation, and pain. There is increasing evidence of TRP channel dysfunction (i.e., TRPV1 and TRPM8) in DED pathophysiology. Here, we review some of this literature and discuss one strategy on how to manage DED using a TRPM8 agonist. -

Cryo-EM Structure of the Polycystic Kidney Disease-Like Channel PKD2L1

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03606-0 OPEN Cryo-EM structure of the polycystic kidney disease-like channel PKD2L1 Qiang Su1,2,3, Feizhuo Hu1,3,4, Yuxia Liu4,5,6,7, Xiaofei Ge1,2, Changlin Mei8, Shengqiang Yu8, Aiwen Shen8, Qiang Zhou1,3,4,9, Chuangye Yan1,2,3,9, Jianlin Lei 1,2,3, Yanqing Zhang1,2,3,9, Xiaodong Liu2,4,5,6,7 & Tingliang Wang1,3,4,9 PKD2L1, also termed TRPP3 from the TRPP subfamily (polycystic TRP channels), is involved 1234567890():,; in the sour sensation and other pH-dependent processes. PKD2L1 is believed to be a non- selective cation channel that can be regulated by voltage, protons, and calcium. Despite its considerable importance, the molecular mechanisms underlying PKD2L1 regulations are largely unknown. Here, we determine the PKD2L1 atomic structure at 3.38 Å resolution by cryo-electron microscopy, whereby side chains of nearly all residues are assigned. Unlike its ortholog PKD2, the pore helix (PH) and transmembrane segment 6 (S6) of PKD2L1, which are involved in upper and lower-gate opening, adopt an open conformation. Structural comparisons of PKD2L1 with a PKD2-based homologous model indicate that the pore domain dilation is coupled to conformational changes of voltage-sensing domains (VSDs) via a series of π–π interactions, suggesting a potential PKD2L1 gating mechanism. 1 Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Protein Science, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China. 2 School of Life Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China. 3 Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Structural Biology, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China. 4 School of Medicine, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China. -

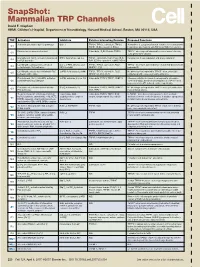

Snapshot: Mammalian TRP Channels David E

SnapShot: Mammalian TRP Channels David E. Clapham HHMI, Children’s Hospital, Department of Neurobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA TRP Activators Inhibitors Putative Interacting Proteins Proposed Functions Activation potentiated by PLC pathways Gd, La TRPC4, TRPC5, calmodulin, TRPC3, Homodimer is a purported stretch-sensitive ion channel; form C1 TRPP1, IP3Rs, caveolin-1, PMCA heteromeric ion channels with TRPC4 or TRPC5 in neurons -/- Pheromone receptor mechanism? Calmodulin, IP3R3, Enkurin, TRPC6 TRPC2 mice respond abnormally to urine-based olfactory C2 cues; pheromone sensing 2+ Diacylglycerol, [Ca ]I, activation potentiated BTP2, flufenamate, Gd, La TRPC1, calmodulin, PLCβ, PLCγ, IP3R, Potential role in vasoregulation and airway regulation C3 by PLC pathways RyR, SERCA, caveolin-1, αSNAP, NCX1 La (100 µM), calmidazolium, activation [Ca2+] , 2-APB, niflumic acid, TRPC1, TRPC5, calmodulin, PLCβ, TRPC4-/- mice have abnormalities in endothelial-based vessel C4 i potentiated by PLC pathways DIDS, La (mM) NHERF1, IP3R permeability La (100 µM), activation potentiated by PLC 2-APB, flufenamate, La (mM) TRPC1, TRPC4, calmodulin, PLCβ, No phenotype yet reported in TRPC5-/- mice; potentially C5 pathways, nitric oxide NHERF1/2, ZO-1, IP3R regulates growth cones and neurite extension 2+ Diacylglycerol, [Ca ]I, 20-HETE, activation 2-APB, amiloride, Cd, La, Gd Calmodulin, TRPC3, TRPC7, FKBP12 Missense mutation in human focal segmental glomerulo- C6 potentiated by PLC pathways sclerosis (FSGS); abnormal vasoregulation in TRPC6-/- -

Involvement of TRPC4 and 5 Channels in Persistent Firing in Hippocampal CA1 Pyramidal Cells

cells Article Involvement of TRPC4 and 5 Channels in Persistent Firing in Hippocampal CA1 Pyramidal Cells Alberto Arboit 1,2,3, Antonio Reboreda 1,4 and Motoharu Yoshida 1,3,4,5,* 1 German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), 39120 Magdeburg, Germany; [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (A.R.) 2 Otto-von-Guericke University, 39120 Magdeburg, Germany 3 Faculty of Psychology, Ruhr University Bochum (RUB), Universitätsstraße 150, 44801 Bochum, Germany 4 Leibniz Institute for Neurobiology (LIN), 39118 Magdeburg, Germany 5 Center for Behavioral Brain Sciences (CBBS), 39106 Magdeburg, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 December 2019; Accepted: 1 February 2020; Published: 5 February 2020 Abstract: Persistent neural activity has been observed in vivo during working memory tasks, and supports short-term (up to tens of seconds) retention of information. While synaptic and intrinsic cellular mechanisms of persistent firing have been proposed, underlying cellular mechanisms are not yet fully understood. In vitro experiments have shown that individual neurons in the hippocampus and other working memory related areas support persistent firing through intrinsic cellular mechanisms that involve the transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels. Recent behavioral studies demonstrating the involvement of TRPC channels on working memory make the hypothesis that TRPC driven persistent firing supports working memory a very attractive one. However, this view has been challenged by recent findings that persistent firing in vitro is unchanged in TRPC knock out (KO) mice. To assess the involvement of TRPC channels further, we tested novel and highly specific TRPC channel blockers in cholinergically induced persistent firing in mice CA1 pyramidal cells for the first time. -

Macromolecular Assembly of Polycystin-2 Intracytosolic C-Terminal Domain

Macromolecular assembly of polycystin-2 intracytosolic C-terminal domain Frederico M. Ferreiraa,b,1, Leandro C. Oliveirac, Gregory G. Germinod, José N. Onuchicc,1, and Luiz F. Onuchica,1 aDivision of Nephrology, University of São Paulo School of Medicine, 01246-903, São Paulo, Brazil; bLaboratory of Immunology, Heart Institute, University of São Paulo School of Medicine, 05403-900, São Paulo, Brazil; cCenter for Theoretical Biological Physics, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093; dNational Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD 20892-2560 Contributed by José N. Onuchic, April 28, 2011 (sent for review March 20, 2011) Mutations in PKD2 are responsible for approximately 15% of the In spite of the aforementioned information and insights, the autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease cases. This gene macromolecular assembly of PC2t homooligomer continued to encodes polycystin-2, a calcium-permeable cation channel whose be an open question. In the current work, we present the most C-terminal intracytosolic tail (PC2t) plays an important role in its comprehensive set of analyses yet performed and that show interaction with a number of different proteins. In the present PC2t forms a homotetrameric oligomer. We have proposed a study, we have comprehensively evaluated the macromolecular PC2 C-terminal domain delimitation and submitted it to a range assembly of PC2t homooligomer using a series of biophysical of biochemical and biophysical evaluations, including chemical and biochemical analyses. Our studies, based on a new delimitation cross-linking, dynamic light scattering (DLS), circular dichroism of PC2t, have revealed that it is capable of assembling as a homo- (CD) and small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) analyses. -

Data-Driven Analysis of TRP Channels in Cancer

CANCER GENOMICS & PROTEOMICS 13 : 83-90 (2016) Data-driven Analysis of TRP Channels in Cancer: Linking Variation in Gene Expression to Clinical Significance YU RANG PARK 1* , JUNG NYEO CHUN 2* , INSUK SO 2, HWA JUNG KIM 3, SEUNGHEE BAEK 4, JU-HONG JEON 2 and SOO-YONG SHIN 1,5 1Office of Clinical Research Information, and Departments of 3Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, and 5Biomedical Informatics, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2Department of Physiology and Biomedical Sciences, Institute of Human-Environment Interface Biology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea; 4Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea Abstract. Background: Experimental evidence has intracellular Ca 2+ in response to various internal and external suggested that transient receptor potential (TRP) channels stimuli (1, 2). In human, the TRP channel superfamily play a crucial role in tumor biology. However, clinical consists of 27 isotypes that are classified into six subfamilies relevance and significance of TRP channels in cancer remain (3): canonical (TRPC), vanilloid (TRPV), melastatin (TRPM), largely unknown. Materials and Methods: We applied a data- polycystin (TRPP), mucolipin (TRPML), and ankyrin driven approach to dissect the expression landscape of 27 (TRPA). Emerging evidence has shown that the aberrant TRP channel genes in 14 types of human cancer using functions of TRP channels are closely associated with cancer International Cancer Genome Consortium data. Results: hallmarks, such as sustaining proliferative signaling, evading TRPM2 was found overexpressed in most tumors, whereas growth suppressors, resisting cell death, and activating TRPM3 was broadly down-regulated. TRPV4 and TRPA1 invasion and metastasis (4, 5). -

The Heteromeric PC-1/PC-2 Polycystin Complex Is Activated by the PC-1 N-Terminus

RESEARCH ARTICLE The heteromeric PC-1/PC-2 polycystin complex is activated by the PC-1 N-terminus Kotdaji Ha1, Mai Nobuhara1, Qinzhe Wang2, Rebecca V Walker3, Feng Qian3, Christoph Schartner1, Erhu Cao2, Markus Delling1* 1Department of Physiology, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, United States; 2Department of Biochemistry, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, United States; 3Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, United States Abstract Mutations in the polycystin proteins, PC-1 and PC-2, result in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and ultimately renal failure. PC-1 and PC-2 enrich on primary cilia, where they are thought to form a heteromeric ion channel complex. However, a functional understanding of the putative PC-1/PC-2 polycystin complex is lacking due to technical hurdles in reliably measuring its activity. Here we successfully reconstitute the PC-1/PC-2 complex in the plasma membrane of mammalian cells and show that it functions as an outwardly rectifying channel. Using both reconstituted and ciliary polycystin channels, we further show that a soluble fragment generated from the N-terminal extracellular domain of PC-1 functions as an intrinsic agonist that is necessary and sufficient for channel activation. We thus propose that autoproteolytic cleavage of the N-terminus of PC-1, a hotspot for ADPKD mutations, produces a soluble ligand in vivo. These findings establish a mechanistic framework for understanding the role of PC-1/PC-2 heteromers in ADPKD and suggest new therapeutic strategies that would expand upon the limited symptomatic treatments currently available for this progressive, terminal disease. -

Opening TRPP2 (PKD2L1) Requires the Transfer of Gating Charges

Opening TRPP2 (PKD2L1) requires the transfer of gating charges Leo C. T. Nga, Thuy N. Viena, Vladimir Yarov-Yarovoyb, and Paul G. DeCaena,1 aDepartment of Pharmacology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL 60611; and bDepartment of Physiology and Membrane Biology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616 Edited by Richard W. Aldrich, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, and approved June 19, 2019 (received for review February 18, 2019) The opening of voltage-gated ion channels is initiated by transfer their ligands (exogenous or endogenous) is sufficient to initiate of gating charges that sense the electric field across the mem- channel opening. Although TRP channels share a similar to- brane. Although transient receptor potential ion channels (TRP) pology with most VGICs, few are intrinsically voltage gated, and are members of this family, their opening is not intrinsically linked most do not have gating charges within their VSD-like domains to membrane potential, and they are generally not considered (16). Current conducted by TRP family members is often rectifying, voltage gated. Here we demonstrate that TRPP2, a member of the but this form of voltage dependence is usually attributed to divalent polycystin subfamily of TRP channels encoded by the PKD2L1 block or other conditional effects (17, 18). There are 3 members of gene, is an exception to this rule. TRPP2 borrows a biophysical riff the polycystin subclass: TRPP1 (PKD2 or polycystin-2), TRPP2 from canonical voltage-gated ion channels, using 2 gating charges (PKD2-L1 or polycystin-L), and TRPP3 (PKD2-L2). TRPP1 is the found in its fourth transmembrane segment (S4) to control its con- founding member of this family, and variants in the PKD2 gene ductive state. -

Ion Channels in the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: a Cutting-Edge Point of View

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Ion Channels in The Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: A Cutting-Edge Point of View 1, 2, 1, Gaetano Riemma y , Antonio Simone Laganà y , Antonio Schiattarella * , Simone Garzon 2 , Luigi Cobellis 1, Raffaele Autiero 1, Federico Licciardi 1, Luigi Della Corte 3 , Marco La Verde 1 and Pasquale De Franciscis 1 1 Department of Woman, Child and General and Specialized Surgery, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, 80138 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (G.R.); [email protected] (L.C.); raff[email protected] (R.A.); [email protected] (F.L.); [email protected] (M.L.V.); [email protected] (P.D.F.) 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, “Filippo Del Ponte” Hospital, University of Insubria, 21100 Varese, Italy; [email protected] (A.S.L.); [email protected] (S.G.) 3 Department of Neuroscience, Reproductive Sciences and Dentistry, School of Medicine, University of Naples Federico II, 80131 Naples, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-392-165-3275 Equal contributions (joint first authors). y Received: 30 December 2019; Accepted: 5 February 2020; Published: 7 February 2020 Abstract: Background: Ion channels play a crucial role in many physiological processes. Several subtypes are expressed in the endometrium. Endometriosis is strictly correlated to estrogens and it is evident that expression and functionality of different ion channels are estrogen-dependent, fluctuating between the menstrual phases. However, their relationship with endometriosis is still unclear. Objective: To summarize the available literature data about the role of ion channels in the etiopathogenesis of endometriosis. -

1 Structural Basis of TRPC4 Regulation by Calmodulin And

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.180778; this version posted July 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Structural basis of TRPC4 regulation by calmodulin and pharmacological agents 2 3 Deivanayagabarathy Vinayagam1, Dennis Quentin1, Oleg Sitsel1, Felipe Merino1,2, Markus 4 Stabrin1, Oliver Hofnagel1, Maolin Yu3, Mark W. Ledeboer3, Goran Malojcic3, Stefan 5 Raunser1 6 7 1Department of Structural Biochemistry, Max Planck Institute of Molecular Physiology, 44227 8 Dortmund, Germany 9 2Current address: Department of Protein Evolution, Max Planck Institute for Developmental 10 Biology, 72076 Tübingen, Germany 11 3Goldfinch Bio, 215 First St, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA 12 Correspondence: [email protected] 13 14 15 ABSTRACT 16 Canonical transient receptor potential channels (TRPC) are involved in receptor-operated 17 and/or store-operated Ca2+ signaling. Inhibition of TRPCs by small molecules was shown to be 18 promising in treating renal diseases. In cells, the channels are regulated by calmodulin. 19 Molecular details of both calmodulin and drug binding have remained elusive so far. Here we 20 report structures of TRPC4 in complex with a pyridazinone-based inhibitor and a pyridazinone- 21 based activator and calmodulin. The structures reveal that both activator and inhibitor bind to 22 the same cavity of the voltage-sensing-like domain and allow us to describe how structural 23 changes from the ligand binding site can be transmitted to the central ion-conducting pore of 24 TRPC4.