Stewarding the Public Opinion: the Boundaries of Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Panther Party “We Want Freedom” - Mumia Abu-Jamal Black Church Model

Women Who Lead Black Panther Party “We Want Freedom” - Mumia Abu-Jamal Black Church model: ● “A predominantly female membership with a predominantly male clergy” (159) Competition: ● “Black Panther Party...gave the women of the BPP far more opportunities to lead...than any of its contemporaries” (161) “We Want Freedom” (pt. 2) Invisibility does not mean non existent: ● “Virtually invisible within the hierarchy of the organization” (159) Sexism does not exist in vacuum: ● “Gender politics, power dynamics, color consciousness, and sexual dominance” (167) “Remembering the Black Panther Party, This Time with Women” Tanya Hamilton, writer and director of NIght Catches Us “A lot of the women I think were kind of the backbone [of the movement],” she said in an interview with Michel Martin. Patti remains the backbone of her community by bailing young men out of jail and raising money for their defense. “Patricia had gone on to become a lawyer but that she was still bailing these guys out… she was still their advocate… showing up when they had their various arraignments.” (NPR) “Although Night Catches Us, like most “war” films, focuses a great deal on male characters, it doesn’t share the genre’s usual macho trappings–big explosions, fast pace, male bonding. Hamilton’s keen attention to minutia and everydayness provides a strong example of how women directors can produce feminist films out of presumably masculine subject matter.” “In stark contrast, Hamilton brings emotional depth and acuity to an era usually fetishized with depictions of overblown, tough-guy black masculinity.” In what ways is the Black Panther Party fetishized? What was the Black Panther Party for Self Defense? The Beginnings ● Founded in October 1966 in Oakland, Cali. -

50Th Anniversary of the Assassination of Illinois Black Panther Chairman Fred Hampton with Dr

50th Anniversary of the Assassination of Illinois Black Panther Chairman Fred Hampton with Dr. Jakobi Williams: library resources to accompany programs FROM THE BULLET TO THE BALLOT: THE ILLINOIS CHAPTER OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AND RACIAL COALITION POLITICS IN CHICAGO. IN CHICAGO by Jakobi Williams: print and e-book copies are on order for ISU from review in Choice: Chicago has long been the proving ground for ethnic and racial political coalition building. In the 1910s-20s, the city experienced substantial black immigration but became in the process the most residentially segregated of all major US cities. During the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, long-simmering frustration and anger led many lower-class blacks to the culturally attractive, militant Black Panther Party. Thus, long before Jesse Jackson's Rainbow Coalition, made famous in the 1980s, or Barack Obama's historic presidential campaigns more recently, the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party (ILPBB) laid much of the groundwork for nontraditional grassroots political activism. The principal architect was a charismatic, marginally educated 20-year-old named Fred Hampton, tragically and brutally murdered by the Chicago police in December 1969 as part of an FBI- backed counter-intelligence program against what it considered subversive political groups. Among other things, Williams (Kentucky) "demonstrates how the ILPBB's community organizing methods and revolutionary self-defense ideology significantly influenced Chicago's machine politics, grassroots organizing, racial coalitions, and political behavior." Williams incorporates previously sealed secret Chicago police files and numerous oral histories. Other review excerpts [Amazon]: A fascinating work that everyone interested in the Black Panther party or racism in Chicago should read.-- Journal of American History A vital historical intervention in African American history, urban and local histories, and Black Power studies. -

Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement

Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato Volume 9 Article 15 2009 Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement Melissa Seifert Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Seifert, Melissa (2009) "Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement," Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato: Vol. 9 , Article 15. Available at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur/vol9/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research Center at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Seifert: Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in t Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement By: Melissa Seifert The origins of the Black Power Movement can be traced back to the civil rights movement’s sit-ins and freedom rides of the late nineteen fifties which conveyed a new racial consciousness within the black community. The initial forms of popular protest led by Martin Luther King Jr. were generally non-violent. However, by the mid-1960s many blacks were becoming increasingly frustrated with the slow pace and limited extent of progressive change. -

William J. Maxwell Curriculum Vitae August 2021

William J. Maxwell curriculum vitae August 2021 Professor of English and African and African-American Studies Washington University in St. Louis 1 Brookings Drive St. Louis, MO 63130-4899 U.S.A. Phone: (217) 898-0784 E-mail: [email protected] _________________________________________ Education: DUKE UNIVERSITY, DURHAM, NC. Ph.D. in English Language and Literature, 1993. M.A. in English Language and Literature, 1987. COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, NEW YORK, NY. B.A. in English Literature, cum laude, 1984. Academic Appointments: WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS, MO. Professor of English and African and African-American Studies, 2015-. Director of English Undergraduate Studies, 2018- 21. Faculty Affiliate, American Culture Studies, 2011-. Director of English Graduate Studies, 2012-15. Associate Professor of English and African and African-American Studies, 2009-15. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN, IL. Associate Professor of English and the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory, 2000-09. Director of English Graduate Studies, 2003-06. Assistant Professor of English and Afro-American Studies, 1994-2000. COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY, WILLIAMSBURG, VA. Visiting Assistant Professor of English, 1996-97. UNIVERSITY OF GENEVA, GENEVA, SWITZERLAND. Assistant (full-time lecturer) in American Literature and Civilization, 1992-94. Awards, Fellowships, and Professional Distinctions: Claude McKay’s lost novel Romance in Marseille, coedited with Gary Edward Holcomb, named one of the ten best books of 2020 by New York Magazine, 2021. Appointed to the Editorial Board of James Baldwin Review, 2019-. Elected Second Vice President (and thus later President) of the international Modernist Studies Association (MSA), 2018; First Vice President, 2019-20; President, 2021-. American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation for my 2015 book F.B. -

Living for the City Donna Jean Murch

Living for the City Donna Jean Murch Published by The University of North Carolina Press Murch, Donna Jean. Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California. The University of North Carolina Press, 2010. Project MUSE. muse.jhu.edu/book/43989. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/43989 [ Access provided at 22 Mar 2021 17:39 GMT from University of Washington @ Seattle ] 5. MEN WITH GUNS In the aftermath of the Watts rebellions, the failure of community pro- grams to remedy chronic unemployment and police brutality prompted a core group of black activists to leave campuses and engage in direct action in the streets.1 The spontaneous uprisings in Watts called attention to the problems faced by California’s migrant communities and created a sense of urgency about police violence and the suffocating conditions of West Coast cities. Increasingly, the tactics of nonviolent passive resistance seemed ir- relevant, and the radicalization of the southern civil rights movement pro- vided a new language and conception for black struggle across the country.2 Stokely Carmichael’s ascendance to the chairmanship of the Student Non- violent Coordinating Committee SNCC( ) in June 1966, combined with the events of the Meredith March, demonstrated the growing appeal of “Black Power.” His speech on the U.C. Berkeley campus in late October encapsu- lated these developments and brought them directly to the East Bay.3 Local activists soon met his call for independent black organizing and institution building in ways that he could not have predicted. -

The Place of Art in Black Panther Party Revolutionary Thought and Practice: from Revolution to Reform, a Content Analysis

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2018 The Place of Art in Black Panther Party Revolutionary Thought and Practice: From Revolution to Reform, A Content Analysis Michael James Macaluso Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Macaluso, Michael James, "The Place of Art in Black Panther Party Revolutionary Thought and Practice: From Revolution to Reform, A Content Analysis" (2018). Dissertations. 3364. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3364 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLACE OF ART IN BLACK PANTHER PARTY REVOLUTIONARY THOUGHT AND PRACTICE: FROM REVOLUTION TO REFORM, A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Michael Macaluso A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Western Michigan University December 2018 Doctoral Committee: Zoann Snyder, Ph.D., Chair Thomas VanValey, Ph.D. Richard Yidana, Ph.D. Douglas Davidson, Ph.D. Copyright by Michael Macaluso 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. Zoann Snyder, Dr. Richard Yidana, Dr. Thomas Lee VanValey, and Dr. Douglas Davidson for agreeing to serve on this committee. Zoann, I want thank you for your patience throughout this journey, I truly appreciate your assistance. Richard, your help with this work has been a significant influence to this study. -

Radical Chic? Yes We Are!

Radical Chic? Yes We Are! Johan Frederik Hartle 23 March 2012 Ever since Tom Wolfe in a classical 1970 essay coined the term "radical chic", upper-class flirtation with radical causes has been ridiculed. But by separating aesthetics from politics Wolfe was actually more reactionary than the people he criticized, writes Johan Frederik Hartle. Even the most practical revolutionaries will be found to have manifested their ideas in the aesthetic sphere. Kenneth Burke, 1936 Newness and the aesthetico-political A discussion of “radical chic” – a term used to denounce criticism and radical thought as something merely fashionable – is, to some extent, a discussion of the new. And while the merely fashionable is, in spite of its pretensions to be innovative and new, still conformist and predictable, being radical is the (sometimes tragic) attempt to differ. Such attempts to differ from prevailing (complacent, bourgeois) agreements are strongly dependent on the jargon of novelty. Therefore we find overlapping dimensions of the aesthetic and the political in the concept of the new. The new itself, a key concept of aesthetic modernity, however, has not always been fashionable. And the category of the new is of course nothing new itself. The new fills archives, whole libraries – and that is, somehow, a paradox in itself. Generations of modernist aestheticians were dealing with the question: why is there aesthetic innovation at all, and how is it possible? With the post-historical exhaustion of history the rejection of the new was cause for a certain satisfaction. Boris Groys argues that: the discourse on the impossibility of the new in art has become especially widespread and influential. -

JOANNE DEBORAH CHESIMARD Act of Terrorism - Domestic Terrorism; Unlawful Flight to Avoid Confinement - Murder

JOANNE DEBORAH CHESIMARD Act of Terrorism - Domestic Terrorism; Unlawful Flight to Avoid Confinement - Murder Photograph Age Progressed to 69 Years Old DESCRIPTION Aliases: Assata Shakur, Joanne Byron, Barbara Odoms, Joanne Chesterman, Joan Davis, Justine Henderson, Mary Davis, Pat Chesimard, Jo-Ann Chesimard, Joanne Debra Chesimard, Joanne D. Byron, Joanne D. Chesimard, Joanne Davis, Chesimard Joanne, Ches Chesimard, Sister-Love Chesimard, Joann Debra Byron Chesimard, Joanne Deborah Byron Chesimard, Joan Chesimard, Josephine Henderson, Carolyn Johnson, Carol Brown, "Ches" Date(s) of Birth Used: July 16, 1947, August 19, 1952 Place of Birth: New York City, New York Hair: Black/Gray Eyes: Brown Height: 5'7" Weight: 135 to 150 pounds Sex: Female Race: Black Citizenship: American Scars and Marks: Chesimard has scars on her chest, abdomen, left shoulder, and left knee. REWARD The FBI is offering a reward of up to $1,000,000 for information directly leading to the apprehension of Joanne Chesimard. REMARKS Chesimard may wear her hair in a variety of styles and dress in African tribal clothing. CAUTION Joanne Chesimard is wanted for escaping from prison in Clinton, New Jersey, while serving a life sentence for murder. On May 2, 1973, Chesimard, who was part of a revolutionary extremist organization known as the Black Liberation Army, and two accomplices were stopped for a motor vehicle violation on the New Jersey Turnpike by two troopers with the New Jersey State Police. At the time, Chesimard was wanted for her involvement in several felonies, including bank robbery. Chesimard and her accomplices opened fire on the troopers. One trooper was wounded and the other was shot and killed execution-style at point-blank range. -

Ursula Mctaggart

RADICALISM IN AMERICA’S “INDUSTRIAL JUNGLE”: METAPHORS OF THE PRIMITIVE AND THE INDUSTRIAL IN ACTIVIST TEXTS Ursula McTaggart Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Departments of English and American Studies Indiana University June 2008 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Purnima Bose, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ Margo Crawford, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ DeWitt Kilgore ________________________________ Robert Terrill June 18, 2008 ii © 2008 Ursula McTaggart ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A host of people have helped make this dissertation possible. My primary thanks go to Purnima Bose and Margo Crawford, who directed the project, offering constant support and invaluable advice. They have been mentors as well as friends throughout this process. Margo’s enthusiasm and brilliant ideas have buoyed my excitement and confidence about the project, while Purnima’s detailed, pragmatic advice has kept it historically grounded, well documented, and on time! Readers De Witt Kilgore and Robert Terrill also provided insight and commentary that have helped shape the final product. In addition, Purnima Bose’s dissertation group of fellow graduate students Anne Delgado, Chia-Li Kao, Laila Amine, and Karen Dillon has stimulated and refined my thinking along the way. Anne, Chia-Li, Laila, and Karen have devoted their own valuable time to reading drafts and making comments even in the midst of their own dissertation work. This dissertation has also been dependent on the activist work of the Black Panther Party, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, the International Socialists, the Socialist Workers Party, and the diverse field of contemporary anarchists. -

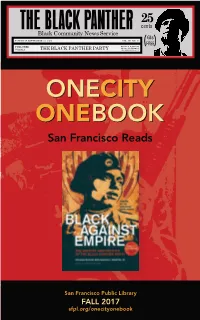

One City One Book 2017 Program Guide

San Francisco Public Library #onecityonebookFALL 2017 @sfpubliclibrary #sfpubliclibrary 2 sfpl.org/onecityonebook WELCOME Dear Readers, We are excited to announce our 13th annual One City One Book title, Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party by authors Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin. The Bay Area is renowned for its activism of the 1960s which helped define the history and culture of our region. Bold, engrossing, and richly detailed, Black against Empire explores the organizations’s genesis, rise and decline— imparting important lessons for Black against Empire is the today’s resistance movements. winner of the American Book Award. The book has been banned by the California Department of Corrections. Read the book and join us for book discussions, themed exhibits, author talks and many other events. City Librarian Luis Herrera 1 Updated event information at sfpl.org/onecityonebook or (415) 557-4277 ABOUT THE BOOK BLACK AGAINST EMPIRE: Black against Empire is the THE HISTORY AND first comprehensive overview POLITICS OF THE BLACK and analysis of the history and PANTHER PARTY politics of the Black Panther This timely special edition, pub- Party. The authors analyze key lished by University of California political questions, such as why Press on the 50th anniversary of so many young black people the founding of the Black Panther across the country risked their Party, features a new preface lives for the revolution, why the by the authors that places the Party grew most rapidly during Party in a contemporary political the height of repression, and why landscape, especially as it relates allies abandoned the Party at to Black Lives Matter and other its peak of influence. -

Picking up the Books: the New Historiography of the Black Panther Party

PICKING UP THE BOOKS: THE NEW HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY David J. Garrow Paul Alkebulan. Survival Pending Revolution: The History of the Black Panther Party. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007. 176 pp. Notes, bibliog- raphy, and index. $28.95. Curtis J. Austin. Up Against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2006. 456 pp. Photographs, notes, bibliography, and index. $34.95. Paul Bass and Douglas W. Rae. Murder in the Model City: The Black Panthers, Yale, and the Redemption of a Killer. New York: Basic Books, 2006. 322 pp. Pho- tographs, notes, bibliography, and index. $26.00. Flores A. Forbes. Will You Die With Me? My Life and the Black Panther Party. New York: Atria Books, 2006. 302 pp. Photographs and index. $26.00. Jama Lazerow and Yohuru Williams, eds. In Search of the Black Panther Party: New Perspectives on a Revolutionary Movement. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006. 390 pp. Notes and index. $84.95 (cloth); $23.95 (paper). Jane Rhodes. Framing the Black Panthers: The Spectacular Rise of a Black Power Icon. New York: The New Press, 2007. 416 pp. Notes, bibliography, and index. $35.00. A comprehensive review of all published scholarship on the Black Panther Party (BPP) leads to the inescapable conclusion that the huge recent upsurge in historical writing about the Panthers begins from a surprisingly weak and modest foundation. More than a decade ago, two major BPP autobiographies, Elaine Brown’s A Taste of Power (1992) and David Hilliard’s This Side of Glory (1993), along with Hugh Pearson’s widely reviewed book on the late BPP co-founder Huey P. -

Modernism and Christian Socialism in the Thought of Ottokã¡R Prohã¡Szka

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 12 Issue 3 Article 6 6-1992 Modernism and Christian Socialism in the Thought of Ottokár Prohászka Leslie A. Muray Lansing Community College, Michigan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Muray, Leslie A. (1992) "Modernism and Christian Socialism in the Thought of Ottokár Prohászka," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 12 : Iss. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol12/iss3/6 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I ; MODERNISM AND CHRISTIAN SOCIALISM IN THE THOUGHT OF OTTOKAR PROHASZKA By Leslie A. Moray Dr. Leslie A. Muray (Episcopalian) is professor of religious studies at the Lansing Community College in Lansing, Michigan. He obtained his Ph.D. degree from the Graduate Theological School in Claremont, California. Several of his previous articles were published in OPREE. Little known in the West is the life and work of the Hungarian Ottokar Prohaszka (1858- 1927), Roman Catholic Bishop of Szekesfehervar and a university professor who was immensely popular and influential in Hungary at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. He was the symbol of modernism, for which three of his works were condemned, and Christian Socialism in his native land.