The Conniving Claimant: Changing Images of Misuse of Legal Remedies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

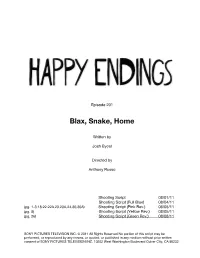

Blax, Snake, Home

Episode 201 Blax, Snake, Home Written by Josh Bycel Directed by Anthony Russo Shooting Script 08/01/11 Shooting Script (Full Blue) 08/04/11 (pg. 1-3,18,22,22A,23,23A,24,30,30A) Shooting Script (Pink Rev.) 08/05/11 (pg. 8) Shooting Script (Yellow Rev.) 08/05/11 (pg. 26) Shooting Script (Green Rev.) 08/08/11 SONY PICTURES TELEVISION INC. © 2011 All Rights Reserved No portion of this script may be performed, or reproduced by any means, or quoted, or published in any medium without prior written consent of SONY PICTURES TELEVISION INC. 10202 West Washington Boulevard Culver City, CA 90232 Happy Endings "Blax, Snake, Home" [201] a. Shooting Script (Pink Rev.) 08/05/11 CAST JANE .................................................................................................... Eliza Coupe ALEX ...............................................................................................Elisha Cuthbert DAVE...........................................................................................Zachary Knighton MAX ...................................................................................................... Adam Pally BRAD .......................................................................................Damon Wayans, Jr. PENNY ...............................................................................................Casey Wilson ANNOUNCER (V.O.)......................................................................................... TBD DARYL (GUY)..............................................................................Brandon -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

TOM ROBINSON ONLY the NOW HOME in the MORNING MERCIFUL GOD (Tom Robinson, Gerry Diver) (Tom Robinson, Gerry Diver, Andy Treacey, Adam Phillips)

TOM ROBINSON ONLY THE NOW HOME IN THE MORNING MERCIFUL GOD (Tom Robinson, Gerry Diver) (Tom Robinson, Gerry Diver, Andy Treacey, Adam Phillips) “He was to remove what Charles My Rolex and phone Shred all my letters “I have a strong faith and pray Fat white maggots Doing a job, I’m doing a job had described, using a wry, Are right there on the table And burn the old polaroids before every mission... I believe With their fat white faces I’m doing a job that all-purpose comic tone... The keys to my car and the flat Stick all those mags in the trash that God’s put me in this job” Crawling all over God put me here for as ‘kinky relics’. The idea was Cut up my credit cards, Empty the treasure chest US bomber pilot, CNN 2003 God’s holy places to spare Charles’s mother.“ Pay off the milkman Under my bed Smoke glass windows Fat white maggots Adam Mars Jones, The Darker Proof Recycle the bills on the mat And flush every crumb Noise and groove by Adam Aircon coaches All blind and bloated The Boss and Armani In my stash Phillips and Andy Treacey with Spewing out locusts They like their reality Are yours if you want ’em Swear on your life additional vocal chords of TV Spewing out roaches Sugar-coated Just stick all the rest in a sack You’ll wipe my hard drive, and Smith and Lee Forsyth Griffiths. There’s only one language Hey Pretty David Then drop the whole lot Smash any backups you find Bass by me. -

Yamaha – Pianosoft Solo 29

YAMAHA – PIANOSOFT SOLO 29 SOLO COLLECTIONS ARTIST SERIES JOHN ARPIN – SARA DAVIS “A TIME FOR LOVE” BUECHNER – MY PHILIP AABERG – 1. A Time for Love 2. My Foolish FAVORITE ENCORES “MONTANA HALF LIGHT” Heart 3. As Time Goes By 4.The 1. Jesu, Joy Of Man’s Desiring 1. Going to the Sun 2. Montana Half Light 3. Slow Dance More I See You 5. Georgia On 2. “Bach Goes to Town” 4.Theme for Naomi 5. Marias River Breakdown 6.The Big My Mind 6. Embraceable You 3. Chanson 4. Golliwog’s Cake Open 7. Madame Sosthene from Belizaire the Cajun 8. 7. Sophisticated Lady 8. I Got It Walk 5. Contradance Diva 9. Before Barbed Wire 10. Upright 11. The Gift Bad and That Ain’t Good 9. 6. La Fille Aux Cheveux De Lin 12. Out of the Frame 13. Swoop Make Believe 10.An Affair to Remember (Our Love Affair) 7. A Giddy Girl 8. La Danse Des Demoiselles 00501169 .................................................................................$34.95 11. Somewhere Along the Way 12. All the Things You Are 9. Serenade Op. 29 10. Melodie Op. 8 No. 3 11. Let’s Call 13.Watch What Happens 14. Unchained Melody the Whole Thing Off A STEVE ALLEN 00501194 .................................................................................$34.95 00501230 .................................................................................$34.95 INTERLUDE 1. The Song Is You 2. These DAVID BENOIT – “SEATTLE MORNING” SARA DAVIS Foolish Things (Remind Me of 1. Waiting for Spring 2. Kei’s Song 3. Strange Meadowlard BUECHNER PLAYS You) 3. Lover Man (Oh Where 4. Linus and Lucy 5. Waltz for Debbie 6. Blue Rondo a la BRAHMS Can You Be) 4. -

Newman V. Google

Case 5:20-cv-04011-VKD Document 1 Filed 06/16/20 Page 1 of 239 1 BROWNE GEORGE ROSS LLP Peter Obstler (State Bar No. 171623) 2 [email protected] 44 Montgomery Street, Suite 1280 3 San Francisco, California 94104 Telephone: (415) 391-7100 4 Facsimile: (310 275-5697 5 Eric M. George (State Bar No. 166403) [email protected] 6 Debi A. Ramos (State Bar No. 135373) [email protected] 7 Keith R. Lorenze (State Bar No. 326894) [email protected] 8 2121 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 2800 Los Angeles, California 90067 9 Telephone: (310) 274-7100 Facsimile: (310) 275-5697 10 Attorneys for Plaintiffs Kimberly Carleste Newman, Lisa 11 Cabrera, Catherine Jones and Denotra Nicole Lewis 12 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 13 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA, SAN JOSE DIVISION 14 15 Kimberly Carleste Newman, Lisa Cabrera, Case No. Catherine Jones, and Denotra Nicole Lewis, 16 CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT FOR Plaintiffs, DECLARATORY JUDGMENT, 17 RESTITUTION AND DAMAGES vs. 18 Google LLC, YouTube LLC, Alphabet Inc, 19 and DOES 1 through 100, inclusive, Trial Date: None Set 20 Defendants. 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 1605366.1 Case No. CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY JUDGMENT, RESTITUTION AND DAMAGES Case 5:20-cv-04011-VKD Document 1 Filed 06/16/20 Page 2 of 239 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Page 3 I. INTRODUCTION AND PREFATORY STATEMENT OF THE CASE .............................. 1 4 II. PARTIES ............................................................................................................................... 14 5 III. JURISDICTION AND VENUE ............................................................................................ 17 6 IV. FACTS COMMON TO ALL CLAIMS ................................................................................ 17 7 A. The Governing Agreements ...................................................................................... 18 8 1. -

Grand Emporium Audiovisual Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

Title of Collection: Grand Emporium Audiovisual Collection Reference Code: US-MoKcUMS-MSA38 Repository: Marr Sound Archives UMKC Miller Nichols Library 800 E. 51st Street Kansas City, MO 64110 Creator: Grand Emporium Naber, Roger Palmer, C. Herb Administrative/Biographical History: In 1979, Roger Naber started booking bands on the side while maintaining a day job for the postal service in Kansas City. Attracting marquee performers to local venues such as the Lone Star, the Uptown Theater, the National Guard Armory, Harling's Upstairs and King Henry's Feast (later known as Parody Hall), he built a rapport with the music world and a reputation as a hardworking promoter. In 1980, he co-founded the Kansas City Blues Society, galvanizing the local music scene during twelve years as the organization's president. His tenacity made him one of Kansas City's most respected promoters, but it was his genuine affinity for musicians that brought success to places like the Grand Emporium. Naber and business partner George Myers bought the Grand Emporium in July 1985, transforming the erstwhile restaurant into a premier destination for live music. From show flyers doubling as wallpaper to a jukebox stocked with old 45s to the makeshift kitchen where "Amazing" Grace Harris served barbecue and soul food, the intimate midtown barroom offered common ground for patron and performer. It was here musicians walked the bar during a guitar solo or took the show outside to Main Street for a song; big name stars were known to drop by for a slice of local flavor after playing bigger, more impersonal area venues; and local legends, such as musician and dancer Speedy Huggins, were fixtures on the scene, cutting up the dance floor and sitting in with bands. -

Developing Critical Reading for Pre-Service English Teachers: Actual Reflections

REPUBLIC OF TURKEY SAKARYA UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING DEVELOPING CRITICAL READING FOR PRE-SERVICE ENGLISH TEACHERS: ACTUAL REFLECTIONS A MASTER’S THESIS YELİZ ÜNAL SUPERVISOR ASSOC. PROF. DR. METİN TİMUÇİN AUGUST 2014 ii REPUBLIC OF TURKEY SAKARYA UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING DEVELOPING CRITICAL READING FOR PRE-SERVICE ENGLISH TEACHERS: ACTUAL REFLECTIONS A MASTER’S THESIS YELİZ ÜNAL SUPERVISOR ASSOC. PROF. DR. METİN TİMUÇİN AUGUST 2014 iii iv v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Some people we have met touch our life and give out light for our success. This study is a result of this kind of experience and I would like to express my deepest gratitude for those contributing to the current study. First and foremost, I would like to present my deepest thanks to my supervisor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Metin Timuçin for his great encouragement, enduring support and valuable advices throughout the process. His understanding and positive attitude helped me to pursue my determination. His enthusiasm and idealistic stand will provide inspiration for my whole teaching career. I would like to express my sincerest thanks to Dean of Faculty of Education at Sakarya University Prof. Dr. Firdevs Karahan for her support and helpful suggestions. I would also like to thank Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Eskicumalı for his interest in this study, participation and contributions. I would like to express thanks to Instructor Ali İlya who helped for organization of critical reading class and separated his valuable class hours for the research. I feel gratitude to Assist. Prof. Dr. Hülya Bartu, who has been acquainted with the ideas and methods of Norman Fairclough at Lancaster University during her post- graduate studies, for sharing her vast knowledge and incredible expertise with us in her course. -

House of Representatives Commonwealth of Pennsylvania **********

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA ********** House Bill 916 Product Liability Issues ********** HOUSE JUDICIARY COMMITTEE HOUSE LABOR RELATIONS COMMITTEE Room 140, Majority Caucus Room Main Capitol Building Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Thursday, October 26, 1989 - 10;00 a.m. — 0O0 — BEFORE : Honorable Thomas R. Caltagirone, Majority Cha i rma n Honorable Mark B. Cohen, Majority Chairman Honorable Nicholas B. Moehlmann, Minority Cha i rman Honorable Jeffrey E. Piccola, Minority Chairman Honorable David K. Levdansky Honorable Andrew J. Carn Honorable Robert L. Freeman Honorable John F. Pressman Honorable Michael R. Veon Honorable Kenneth E. Brandt Honorable Edgar A. Carlson Honorable J. Scot Chadwick Honorable Joseph M. Gladeck, Jr. Honorable David W. Heckler Honorable Kenneth E. Lee Honorable Ronald S. Marsico Honorable Jere L. Strittmatter , Honorable Christopher McNally to" Honorable Michael E. Bortner filAO ^ K KEY REPORTERS (717) 757-4401 (YORK) <^/ BEFORE (CONT'D) : Honorable Richard Hayden Honorable Joseph Lashinger, Jr. Honorable Lois Sherman Hagarty Honorable Robert D. Reber, Jr. Honorable Karen A. Ritter Honorable Michael C. Gruitza Honorable Paul McHale Honorable Gerald A. Kosinski STAFF MEMBERS: (Labor Relations Committee) Michael Cassidy Majority Executive Director Nevin J. Mindlin Minority Executive Director James M. Trammell, II Minority Research Analyst STAFF MEMBERS: (Judiciary Committee) Katherine Manucci Executive Secretary William H. Andring, Esquire Majority Chief Counsel David Krantz Majority Executive -

Media Studies 11-12 Textbook

Media Study Guides by Teachers in EDCP 481 Table of Contents Identity & Culture 1. Ma Vie en Rose (Lucas Mann & Marie-Anne Hellinckx) 2. Mean Girls (Chelsea Campbell & Michelle Fatkin) 3. Little Miss Sunshine (Chris Howey & Yik Wah Penner) 4. A Warrior’s Religion (Paramjit Koka & Rupinder Grewal) 5. Thirteen (Kelly Skehill & Kat Ast) 6. 16 and Pregnant (Thomas Froh & Peter Maxwell) 7. My Sister’s Keeper (Stephanie Malloy & Jon Schmidt) 8. One Week (Ashley MacKenzie & Alex Thureau) 9. Schindler’s List (Paul Eberhardt & Rhonda Lochhead) 10. Family Guy & The Simpsons (Amerdeep Nann & Ashley Bayles) 11. Bright Star (Mark Brown) 12. Freedom Writers (Grace Woo & Chris Flannelly) 13. Schindler’s List (Jennifer Olson, Jenn Mansour & Sarah Kharikian) 14. The Television Family (Melissa Evans & Shaun Beach) Culture, Fiction, Power, and Politics 15. Lord of the Rings (Lance Peters & Alex McKillop) 16. The Dark Knight (Adam Deboer & Alvin Lui) 17. Advertising & the End of the World (Safi Arnold & Zachary Pinette) 18. The Office (Fay Sterne & Brittaney Boone) 19. The Corporation (Michael Wuensche & John Ames) 20. Outsourced (Michael Bui & Jennifer Neff) 21. Food Inc. (Liilian Ryan & Sarah James) 22. Mad Men (Graham Haigh & Dean Morris) Environment, Ecology, and Reality 23. Avatar (Wendy Sigaty & Haley Lucas) 24. Wall-e (Rachel Fales & Jennifer Visser) 25. Into the Wild (Kady Huhn and Hannah Yu) 26. Wall-e (Kara Troke and Taha Anjarwalla) 27. 127 Hours (Nick De Santis & Nam Pham) 28. Lost (Dianna Stashuk and Adam Alvaro) Music and Gaming Culture 29. Where is the Love? (Stef Dubrowski & Jess Lee) 30. Popular Music and Videos (Alexander McKechnie) 31. -

The Circulation of Popular Dance on Youtube

Social Texts, Social Audiences, Social Worlds: The Circulation of Popular Dance on YouTube Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alexandra Harlig Graduate Program in Dance The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Harmony Bench, Advisor Katherine Borland Karen Eliot Ryan Skinner Copyrighted by Alexandra Harlig 2019 2 Abstract Since its premiere, YouTube has rapidly emerged as the most important venue shaping popular dance practitioners and consumers, introducing paradigm shifts in the ways dances are learned, practiced, and shared. YouTube is a technological platform, an economic system, and a means of social affiliation and expression. In this dissertation, I contribute to ongoing debates on the social, political, and economic effects of technological change by focusing on the bodily and emotional labor performed and archived on the site in videos, comments sections, and advertisements. In particular I look at comments and fan video as social paratexts which shape dance reception and production through policing genre, citationality, and legitimacy; position studio dance class videos as an Internet screendance genre which entextualizes the pedagogical context through creative documentation; and analyze the use of dance in online advertisements to promote identity-based consumption. Taken together, these inquiries show that YouTube perpetuates and reshapes established modes and genres of production, distribution, and consumption. These phenomena require an analysis that accounts for their multivalence and the ways the texts circulating on YouTube subvert existing categories, binaries, and hierarchies. A cyclical exchange—between perpetuation and innovation, subculture and pop culture, amateur and professional, the subversive and the neoliberal—is what defines YouTube and the investigation I undertake in this dissertation. -

HIT SONG! Book, Music and Lyrics by Keith Edwards

HIT SONG! Book, Music and Lyrics by Keith Edwards © 2015 by Keith Edwards 252 W. 30th Street #15 Registered WGAW New York, NY 10001 Phone: (520) 780-9336 Email: [email protected] Hit Song! 9/19/15 Synopsis “Hit Song!” is a new musical about an autistic 12-year old boy who along with his mother is abandoned by his country music star father. When tragedy strikes and his mother takes her own life, his father returns and finds that his son helps him as much as he helps his son as they connect with their mutual love for music.” Characters BILLY Phoenix: Johnny’s twelve-year-old son, on the Autism Spectrum. As with many people on the Autism Spectrum, Billy is quirky and has large mood swings. Under stress Billy presents with “hand flapping” and other symptoms. He avoids eye contact and does not like to be touched. Billy has a rich inner-life where he is creative and perceptive. Johnny “Phoenix” Canyon: Johnny is around 45 years old, and BILLY’s father. He’s a real authentic Nashville country music star, tall and lanky with a great voice, really good rhythm guitar player, and a lot of charisma. He dresses in “Country” style cowboy boots, hat, blue jeans, etc. Johnny tends to drink too much and is prone to telling “half truth’s”. Lexie Le Barnes: Billy’s school Guidance Counselor about 35 years old. Lexie has beauty, and she’s got grit. She possesses a strong singing and speaking voice. Lexie practices “tough” love. Karaoke Sue: Attractive “bar fly”. -

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE POP SOLOS Packet by Victoria, for Use As OFFICIAL MATCH During Week 3 of Season 1 2/8/2021

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE POP SOLOS Packet by Victoria, For use as OFFICIAL MATCH during Week 3 of Season 1 2/8/2021 Scorer at https://wikiquiz.org/Quiz_Scorer_App.html (use the link on quizcentral.net/matches.php) Correct as of 1/27/2021 Round 1 1a Arguably one of the most successful winners in reality show history is what "Next Food Network Star" champion who went on to host "Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives"? Guy FIERI (accept Guy FERRY) 1b In 2020, Kpop group Blackpink had their first top 20 hit on the Billboard Hot 100 with "Ice Cream". This song was a collaboration with which high-profile musician, a formerly ubiquitous presence on the Disney Channel whose most recent album "Rare" included her first-ever #1 hit, "Lose You to Love Me". Selena GOMEZ 1c Which Austrian-German automaker's first vehicle, known as the P1 or Egger-Lohner, was created in 1898 and is considered to be among the very first electric cars? More recently, the company named for him prototyped an electric version of their Boxster model in 2011, and began selling an electric vehicle called the Taycan this year. Ferdinand PORSCHE 2a In a 2014 Walk the Moon single, the woman who is the singer's destiny tells him to "shut up and"......WHAT? DANCE (with me) 2b The Oscar-nominated actor Michael Shannon made his debut in which 1993 film? The action of the movie was estimated in the original screenplay to last for 10,000 years, although the film's director later scaled that back to "thirty or forty years" in a 2009 interview.