39 Silent Killers of Your Fantasy Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predestination As a Motif in Faulkner's Light in August Virginia A

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1976 Predestination as a Motif in Faulkner's Light in August Virginia A. Riegel Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Riegel, Virginia A., "Predestination as a Motif in Faulkner's Light in August" (1976). Masters Theses. 3441. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3441 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings • . 11 I respectfully request Booth Library of .Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because---------------- Date Author pdm Predestination as a Motif in Faulkner' s Light in August (TITLE) BY Virginia A. Riegel- B.S. -

2016 PHILADELPHIA PHILLIES (71-91) Fourth Place, National League East Division, -24.0 Games Manager: Pete Mackanin, 2Nd Season

2016 PHILADELPHIA PHILLIES (71-91) Fourth Place, National League East Division, -24.0 Games Manager: Pete Mackanin, 2nd season 2016 SEASON RECAP: Philadelphia went 71-91 (.438) in 2016, an eight-win improvement from the previous year (63 W, .388 win %) … It marked the Phillies fourth consecutive season under .500 (73- PHILLIES PHACTS 89 in both 2013 & 2014, 63-99 in 2015), which is their longest streak since they posted seven consecutive Record: 71-91 (.438) losing seasons from 1994 to 2000 ... The Phillies finished in 4th place in the NL East, 24.0 games behind Home: 37-44 the Washington Nationals, and posted 90 or more losses in a season for the 39th time in club history … Road: 34-47 Philadelphia had 99 losses in 2015, marking the first time they have had 90+ losses in back-to-back Current Streak: Won 1 Last 5 Games: 1-4 seasons since 1996-97 (95, 94) … Overall, the club batted .240 this year with a .301 OBP, .384 SLG, Last 10 Games: 2-8 .685 OPS, 427 extra-base hits (231 2B, 35 3B, 161 HR) and a ML-low 610 runs scored (3.77 RPG) … Series Record: 18-28-6 Phillies pitchers combined for a 4.63 ERA (739 ER, 1437.0 IP), which included a 4.41 ERA for the starters Sweeps/Swept: 6/9 and a 5.01 mark for the pen. PHILLIES AT HOME HOT START, COOL FINISH: Philadelphia began the season with a 24-17 record over their first 41 th Games Played: 81 games … Their .585 winning percentage over that period (4/4-5/18) was the 6 -best in MLB, trailing Record: 37-44 (.457) only the Chicago Cubs (.718, 28-11), Baltimore Orioles (.615, 24-15), Boston Red Sox (.610, 25-16), CBP (est. -

2016 Annual Report

2016 Annual Report Gateway Economic Development Corporation of Greater Cleveland TABLE OF CONTENTS DEAR CITIZENS PAGE 3 PROGRESSIVE FIELD PAGE 6 QUICKEN LOANS ARENA PAGE 10 FINANCIALS PAGE 17 Photo taken by Aaron Josefczk Gateway Economic Development Corporation of Greater Cleveland 758 Bolivar Cleveland, OH 44115 DEAR CITIZENS OF CUYAHOGA COUNTY It is with pride that we provide you with our annual report for 2016 featuring our audited financial statements for the fiscal year ending December 31, 2016. Gateway Economic Development Corporation of Greater Cleveland (Gateway) was formed in 1990 by the City of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County, for the purposes of financing, building, owning and operating the Gateway Sports Complex in downtown Cleveland. Gateway owns Quicken Loans Arena, as well as Progressive Field and surrounding common areas, including Gateway Plaza along Ontario Avenue. Gateway’s lease agreements with the Cleveland Indians and the Cleveland Cavaliers, as revised and extended in 2004 and 2007, facilitate Gateway’s ability to continue as a good steward of these two tremendous buildings, as it has been for a generation. The leases with the Indians and the Cavaliers require the teams to pay for operating and maintenance costs of their respective facilities, many of the capital repair costs, as well as all of the cost of operating the Gateway Corporation. Gateway’s responsibilities – pursuant to a budget agreed upon annually with the teams and financed by team rental payments - include common area maintenance, insurance, security, and oversight of the maintenance and capital repairs of the ballpark and the arena, ensuring that Gateway’s facilities are maintained to guarantee their long-term viability. -

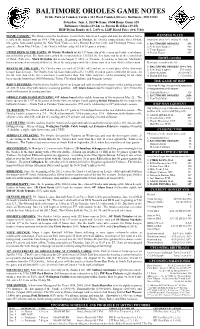

Baltimore Orioles Game Notes

BALTIMORE ORIOLES GAME NOTES ORIOLE PARK AT CAMDEN YARDS • 333 WEST CAMDEN STREET • BALTIMORE, MD 21201 MONDAY, AUGUST 20, 2018 • GAME #125 • ROAD GAME #64 BALTIMORE ORIOLES (37-87) at TORONTO BLUE JAYS (55-69) RHP Andrew Cashner (4-10, 4.71) vs. RHP Marco Estrada (6-9, 4.87) CEDRIC THE ENTERTAINER: OF Cedric Mullins went 2-for-3 on Sunday at Cleveland and hit his first career home run Saturday...Since I’VE GOT YOUR BACK making his Major League debut on August 10, he is batting .387 (12-for-31) and six of his 12 hits are extra-base hits...Mullins has five Lowest inherited runners scored percentage in doubles through nine career games...He is the first Orioles batter with at least five doubles through nine career games since current Orioles the American League (by team): assistant hitting coach Howie Clark notched five doubles in 2002...Since making his debut on August 10, Mullins’ .387 batting average 1. Los Angeles-AL 20.6% (43-of-209) leads AL rookies and ranks second in the majors among rookies behind Atlanta’s Ronald Acuña, Jr. (.450)...His five doubles since August 2. Houston 24.6% (32-of-130) 10 are tied for second-most in the majors among rookies. 3. Cleveland 27.0% (48-for-178) 4. Boston 28.2% (37-of-131) BREAKING NEWS: The Orioles rank among league leaders in several major offensive categories since the All-Star break, including 5. BALTIMORE 29.1% (67-of-230) ranking third in the majors in batting average at .276 (257-for-931)...They have recorded 257 hits in 26 games since the All-Star break, 6. -

And Solidarity

Contingency,rencYrlfooY, andsolidarity RICHARD RORTY U niaersityProfessor of Hamanities, Uniaersityof Virginia ry,,,*-_qCaUBRTDGE WP uNrvERsrrY PREss Published by the PressSyndicarc of dre University of Cambridge The Pitt Building Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 IRP 40 Vest 20th Suect, New York, NY 10011-4211,USA l0 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia @ Cambridgc University Press1989 First published 1989 Reprinted 1989 (thrice), 1990, l99l (cwice), 1992, 1993, 1994, r995 Printed in the United Sratesof America Library of Congess Catdoging-in-Publication Daa is available British Library Cataloging in Publication applied for ISBN0-521 -3538r -5 hardback ISBN0-52 I -1678l -6 paperback In memory of six liberals: my parentsand grandparents The agdlasrer lRabelais's word for those who do not laughJ, the non- thought of received ideas, and kitsch are one and the same, the three- headed enemy of the art born as the echo of God's laughter, the art that created the fascinating imaginative realm where no one owns the truth and everyone has the right to be understood. That imaginative realm of tolerance was born with modern Europe, it is the very image of Europe- of at least our dream of Europe, a dream many times betrayed but nonetheless strong enough to unite us all in the fraternity that stretches far beyond the little European continent. But we know that the wodd where the individual is respected (the imaginative world of the novel, and the real one of Europe) is fragile and perishable. if European culture seems under threat today, if the threat from within and without hangs over what is most precious about it - its respect for the individual, for his original thought, and for his right to an inviolable private life - then, I believe, that precious essenceof the European spirit is being held safe as in a treasure chest inside the history of the novel, the wisdom of the novel. -

Oregon State's Rutschman Named 2019 Dick Howser

DICK HOWSER TROPHY COMMITTEE Contact: Bo Carter ([email protected]) June 15, 2019 OREGON STATE’S RUTSCHMAN NAMED 2019 DICK HOWSER TROPHY RECIPIENT OMAHA, Neb. – Catcher Adley Rutschman of Oregon State is the 33rd recipient of the Dick Howser Trophy, presented by The Game Headwear, as college baseball's Player of the Year. The announcement came at a national news conference Saturday morning at TD Ameritrade Stadium as OSU’s first winner of the prestigious award met with a group of national media. He is the first Beavers player honored with the Howser Trophy, which originated in 1987. Rutschman also is the fourth recipient to be the first overall selection in the Major League Baseball free agent draft and capture the award, joining Clemson pitcher Kris Benson (1996), Vanderbilt pitcher David Price (2007) and San Diego State pitcher Steve Strasburg (2008). Rutchsman was selected by the Baltimore Orioles as the opening player in last week’s draft. The 2019 consensus first team All-America choice was honored in voting by the Howser Trophy committee and the National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association. He is the second all-time winner from the Pac-12 Conference after Mark Prior of Southern California captured the 2001 honor. Rutschman, a 6-2, 216-pound switch hitting and righty throwing junior catcher from Sherwood, Ore., also was the 2019 Pac-12 Player of the Year, the Pac-12 Defensive Player of the Year, and a finalist for the Buster Posey Award, which honors the nation’s top catcher in 2019 and is named in honor of the 2008 Dick Howser Trophy recipient. -

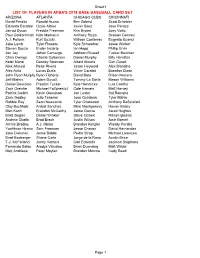

List of Players in Apba's 2018 Base Baseball Card

Sheet1 LIST OF PLAYERS IN APBA'S 2018 BASE BASEBALL CARD SET ARIZONA ATLANTA CHICAGO CUBS CINCINNATI David Peralta Ronald Acuna Ben Zobrist Scott Schebler Eduardo Escobar Ozzie Albies Javier Baez Jose Peraza Jarrod Dyson Freddie Freeman Kris Bryant Joey Votto Paul Goldschmidt Nick Markakis Anthony Rizzo Scooter Gennett A.J. Pollock Kurt Suzuki Willson Contreras Eugenio Suarez Jake Lamb Tyler Flowers Kyle Schwarber Jesse Winker Steven Souza Ender Inciarte Ian Happ Phillip Ervin Jon Jay Johan Camargo Addison Russell Tucker Barnhart Chris Owings Charlie Culberson Daniel Murphy Billy Hamilton Ketel Marte Dansby Swanson Albert Almora Curt Casali Nick Ahmed Rene Rivera Jason Heyward Alex Blandino Alex Avila Lucas Duda Victor Caratini Brandon Dixon John Ryan Murphy Ryan Flaherty David Bote Dilson Herrera Jeff Mathis Adam Duvall Tommy La Stella Mason Williams Daniel Descalso Preston Tucker Kyle Hendricks Luis Castillo Zack Greinke Michael Foltynewicz Cole Hamels Matt Harvey Patrick Corbin Kevin Gausman Jon Lester Sal Romano Zack Godley Julio Teheran Jose Quintana Tyler Mahle Robbie Ray Sean Newcomb Tyler Chatwood Anthony DeSclafani Clay Buchholz Anibal Sanchez Mike Montgomery Homer Bailey Matt Koch Brandon McCarthy Jaime Garcia Jared Hughes Brad Ziegler Daniel Winkler Steve Cishek Raisel Iglesias Andrew Chafin Brad Brach Justin Wilson Amir Garrett Archie Bradley A.J. Minter Brandon Kintzler Wandy Peralta Yoshihisa Hirano Sam Freeman Jesse Chavez David Hernandez Jake Diekman Jesse Biddle Pedro Strop Michael Lorenzen Brad Boxberger Shane Carle Jorge de la Rosa Austin Brice T.J. McFarland Jonny Venters Carl Edwards Jackson Stephens Fernando Salas Arodys Vizcaino Brian Duensing Matt Wisler Matt Andriese Peter Moylan Brandon Morrow Cody Reed Page 1 Sheet1 COLORADO LOS ANGELES MIAMI MILWAUKEE Charlie Blackmon Chris Taylor Derek Dietrich Lorenzo Cain D.J. -

Baltimore Orioles Game Notes

BALTIMORE ORIOLES GAME NOTES ORIOLE PARK AT CAMDEN YARDS • 333 WEST CAMDEN STREET • BALTIMORE, MD 21201 THURSDAY, MAY 24, 2018 • GAME #50 • ROAD GAME #27 BALTIMORE ORIOLES (15-34) at CHICAGO WHITE SOX (15-31) RHP Dylan Bundy (2-6, 4.70) vs. RHP Lucas Giolito (3-4, 6.42) WHAT A DIFFERENCE A DAY MAKES: RHP Dylan Bundy makes his fi fth day-game start of the season...He has gone 1-1 with a 0.70 MAN-NY OF THE YEAR ERA (2 ER/25.2 IP) in four starts during the daytime this season...His 0.70 daytime ERA leads the majors (min. three daytime starts)...In Manny Machado’s current AL and MLB ranks: his career, Bundy has gone 6-6 with a 4.75 ERA (57 ER/108.0 IP) in 25 career day games (17 starts). Batting Average (.328) 4th AL 6th MLB Home Runs (15) T-2nd AL T-2nd MLB DOUBLE DARE: LF Trey Mancini notched two outfi eld assists in the bottom of the fi fth inning on Monday night at Chicago...According to RBI (43) 1st AL 1st MLB the Elias Sports Bureau, Mancini is one of just two players in Orioles history (since 1954) with two outfi eld assists in the same inning (also Hits (62) T-3rd AL T-4th MLB LF Don Buford on June 25, 1970 at Boston in the fi rst inning)...According to STATS, LLC., the last player in the majors with two outfi eld Extra-base Hits (28) T-2nd AL T-3rd MLB assists in the same inning was LF José Osuna of the Pittsburgh Pirates, who did so on July 6, 2017 at Philadelphia in the second inning.. -

2010 Topps Baseball Set Checklist

2010 TOPPS BASEBALL SET CHECKLIST 1 Prince Fielder 2 Buster Posey RC 3 Derrek Lee 4 Hanley Ramirez / Pablo Sandoval / Albert Pujols LL 5 Texas Rangers TC 6 Chicago White Sox FH 7 Mickey Mantle 8 Joe Mauer / Ichiro / Derek Jeter LL 9 Tim Lincecum NL CY 10 Clayton Kershaw 11 Orlando Cabrera 12 Doug Davis 13 Melvin Mora 14 Ted Lilly 15 Bobby Abreu 16 Johnny Cueto 17 Dexter Fowler 18 Tim Stauffer 19 Felipe Lopez 20 Tommy Hanson 21 Cristian Guzman 22 Anthony Swarzak 23 Shane Victorino 24 John Maine 25 Adam Jones 26 Zach Duke 27 Lance Berkman / Mike Hampton CC 28 Jonathan Sanchez 29 Aubrey Huff 30 Victor Martinez 31 Jason Grilli 32 Cincinnati Reds TC 33 Adam Moore RC 34 Michael Dunn RC 35 Rick Porcello 36 Tobi Stoner RC 37 Garret Anderson 38 Houston Astros TC 39 Jeff Baker 40 Josh Johnson 41 Los Angeles Dodgers FH 42 Prince Fielder / Ryan Howard / Albert Pujols LL Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Marco Scutaro 44 Howie Kendrick 45 David Hernandez 46 Chad Tracy 47 Brad Penny 48 Joey Votto 49 Jorge De La Rosa 50 Zack Greinke 51 Eric Young Jr 52 Billy Butler 53 Craig Counsell 54 John Lackey 55 Manny Ramirez 56 Andy Pettitte 57 CC Sabathia 58 Kyle Blanks 59 Kevin Gregg 60 David Wright 61 Skip Schumaker 62 Kevin Millwood 63 Josh Bard 64 Drew Stubbs RC 65 Nick Swisher 66 Kyle Phillips RC 67 Matt LaPorta 68 Brandon Inge 69 Kansas City Royals TC 70 Cole Hamels 71 Mike Hampton 72 Milwaukee Brewers FH 73 Adam Wainwright / Chris Carpenter / Jorge De La Ro LL 74 Casey Blake 75 Adrian Gonzalez 76 Joe Saunders 77 Kenshin Kawakami 78 Cesar Izturis 79 Francisco Cordero 80 Tim Lincecum 81 Ryan Theroit 82 Jason Marquis 83 Mark Teahen 84 Nate Robertson 85 Ken Griffey, Jr. -

Yankees First Baseman Mark Teixeira Joins Arizona Fall League Hall Of

For Immediate Release Friday, November 2, 2012 Yankees First Baseman Mark Teixeira Joins Arizona Fall League Hall of Fame Phoenix, Arizona — New York Yankees first baseman Mark Teixeira, a Facts member of the 2002 Peoria Javelinas, joins the Arizona Fall League Hall of Fame • More than 2,100 of over 3,500 tonight in pre-game ceremonies at Scottsdale Stadium (Rafters vs. Scorpions). (60%) Fall Leaguers have reached the major leagues “Mark has been a remarkably consistent professional throughout his standout • 184 MLB All-Stars career,” says Fall League Director Steve Cobb. • 10 MLB MVPs Teixeria’s consistency includes 2 All-Star Games, 5 Gold Gloves, 3 Silver •Ryan Braun •Jason Giambi Slugger awards and a World Series championship right with the 2009 Yankees. •Josh Hamilton He has homered from both sides of the plate in the same game 13 times, the •Ryan Howard MLB record. •Joe Mauer •Justin Morneau The fastest switch-hitter to 300 home runs in major-league history, Teixeria •Dustin Pedroia is also the first switch-hitter with 20 home runs in each of his first 11 major- •Albert Pujols (3) •Jimmy Rollins league seasons. He was the only major leaguer to reach 30 home runs and 100 •Joey Votto RBI for eight consecutive seasons from 2004–11. • 3 Cy Young Award winners Defensively, Teixeria is the American League career fielding percentage •Chris Carpenter •Roy Halladay (2) leader among first basemen (minimum 1000 games). He won his fifth Gold Glove •Brandon Webb earlier this week. • 3 World Series MVPs He also participated in the 2005 All-Star Game Home Run Derby. -

Oakland Athletics Post Game Notes

OAKLAND ATHLETICS POST GAME NOTES Oakland Athletics Baseball Company • 510-638-4900 • athletics.com • A’s PR @AsMediaAlerts OAKLAND ATHLETICS (76-51) VS. TEXAS RANGERS (57-72) WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 22, 2018— OAKLAND COLISEUM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E Texas 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 4 9 0 Oakland 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 2 4 0 Win: Mike Minor (10-6) Loss: Edwin Jackson (4-3) OAKLAND NOTES TEXAS NOTES • Edwin Jackson allowed four runs on seven hits across • Mike Minor turned in his second scoreless outing of the 4.1 innings...the outing tied a season-low in innings season (6/27 vs. San Diego), and his third quality start and matched a season-high in hits...the leadoff home in his last four starts...he recorded his 10th win of 2018, run surrendered to Shin-Soo Choo marked the end of a the first time he has reached the mark since a 13-win 19-inning scoreless run by Oakland pitchers. season with Atlanta in 2013. • Stephen Piscotty tied a career high with 35 doubles, • Shin-Soo Choo homered on the first pitch of the game, which are the most on the team...entered the day tied the 14th first-pitch homer in the MLB this season...it for ninth in the American League in doubles. was Choo's fourth leadoff homer of 2018, his 16th with Texas, and the 27th of his career. • In six appearances and 5.1 innings pitched with the Ath- letics, Shawn Kelley has not allowed a run...in six out- • Choo has now reached safely in 13 straight games, his ings and 6 innings pitched with the A's, Fernando Rod- longest such streak since a career-long 52-game streak ney has not allowed a run. -

BALTIMORE ORIOLES GAME NOTES Oriole Park at Camden Yards 333 West Camden Street Baltimore, MD 21201

BALTIMORE ORIOLES GAME NOTES Oriole Park at Camden Yards 333 West Camden Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Saturday, June 3, 2017 Game #54 Home Game #28 Baltimore Orioles (29-24) vs. Boston Red Sox (29-25) RHP Dylan Bundy (6-3, 2.89) vs. LHP David Price (0-0, 5.40) WINNING WAYS HOME COOKIN’: The Orioles own the best home record in the American League and own the third-best home record in the majors with an 19-8 (.704) mark…Beginning on Monday, the Orioles returned home for a 10-day, Most wins since 2012 among AL clubs: nine-game homestand against the New York Yankees (2-1), Boston Red Sox (2-0), and Pittsburgh Pirates (two 1. BALTIMORE ORIOLES 473 games)…From May 19-June 7, the Orioles will have played 15 of 18 games at home. 2. New York Yankees 466 3. Texas Rangers 460 UPPER DECK IS THE TOPPS: 3B Manny Machado hit his 11th home run of the season on Friday, a solo home 4. Detroit Tigers 457 run in his first at-bat...The home run reached the second deck in left field, the first home run hit to the second deck HOME GOODS of Oriole Park since Mark Reynolds did so on August 7, 2011 vs. Toronto...According to Statcast, Machado's homer measured an estimated 465 feet...He is the only player with three home runs of at least 460 feet this season. Best home records in the AL: 1. BALTIMORE ORIOLES 19-8 (.704) BEASTS OF THE EAST: The Orioles own a record of 29-24 (.547) and are in second place of the American 2.