Psalm 15 in Greek: Text-Production and Text-Reception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sermon Title: “THE ACCEPTABLE LIFE: an UNSHAKABLE LIFE! Sermon Text: Psalm 15 Introduction: GOOD MORNING to ALL! for THOSE

Sermon Title: “THE ACCEPTABLE LIFE: AN UNSHAKABLE LIFE! Sermon Text: Psalm 15 Introduction: GOOD MORNING TO ALL! FOR THOSE WHO ARE WITH US FOR THE FIRST TIME WE ARE NOW STUDYING THE BOOK OF PSALMS UNDER THE THEME “PONDERING THE PSALMS: FINDING MEANING & PIRPOSE IN THE PANDEMIC!” LET US READ PSALM 15 TOGETHER AGAIN! LAST TUESDAY, THE CITY OF BEIRUT WAS ROCKED BY A BIG EXPLOSION THAT SHOOK THE CITY TO ITS CORE! THE EXPLOSION WAS SO LOUD THAT EVEN NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES OF LEBANON HEARD THE SOUND OF THE EXPLOSION. AS IF THIS TIME, THE EXPLOSION LEFT 157 DEAD (THEY ARE STILL SEARCHING FOR PEOPLE AMONG THE RUBLES!), MORE THAN 5,000 INJURED/HOSPITALIZED, 300,000 HOMELESS, AND MILLIONS OF DOLLARS OF PROPERTIES DAMAGED, & LEBANON’S ECONOMY CRIPPLED! THE PEOPLE OF LEBANON ARE NOW BLAMING THIS TRAGEDY TO THEIR GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS & ARE PROTESTING IN THE STREETS & CALLING ON THEM TO RESIGN! ONE LEBANESE SAID THIS EXPLOSION SENT THE NATION 50 YEARS BACKWARDS BECAUSE OF ALL THIS LOSS. INDEED, THIS EXPLOSION HAS SHAKEN THE LEBANESE PEOPLE TO THEIR CORE! CHURCH/FRIENDS, HOW IS YOUR LIFE NOWADAYS IN THIS PANDEMIC? ARE YOU BEING SHAKEN TO THE CORE BY THIS PANDEMIC? UNLIKE THE LEBANON EXPLOSION THAT SHOOK THE NATION ONE TIME, THE COVID VIRUS EXPLOSION IS STILL CONTINUING & IS STILL SHAKING PEOPLE’S LIVES IN A SUBTLE, DECEITFUL, & INSIDIOUS WAY! PERHAPS, SOME OF US ARE SAYING “NO, I’M OKAY! I CAN MANAGE THIS. IM GOOD!’ BUT THE WAY WE LIVE OUR LIVES NOWADAYS DENIES OR CONTRADICTS WHAT WE SAY! TODAY, WE ARE GOING TO STUDY A PRAYER OF DAVID THAT WILL TEACH US HOW TO HAVE AN UNSHAKABLE LIFE! I BELIEVE THIS IS WHAT WE TRULY NEED AT THIS TIME! CAN WE PAUSE FOR PRAYER! OUR PSALM TODAY WILL REMIND US THAT A CRISIS SHOULD NOT CHANGE OUR ZEAL & DEVOTION TO THE LORD. -

"Who Shall Ascend Into the Mountain of the Lord?": Three Biblical Temple Entrance Hymns

"Who Shall Ascend into the Mountain of the Lord?": Three Biblical Temple Entrance Hymns Donald W. Parry A number of the psalms in the biblical Psalter1 pertain directly to the temple2 and its worshipers. For instance, Psalms 29, 95, and 100 pertain to worshipers who praise the Lord as he sits enthroned in his temple; Psalm 30 is a hymn that was presumably sung at the dedication of Solomon’s temple; Psalms 47, 93, and 96 through 99 are kingship and enthronement psalms that celebrate God’s glory as king over all his creations; Psalms 48, 76, 87, and 122 are hymns that relate to Zion and her temple; Psalm 84 is a pilgrim’s song, which was perhaps sung by temple visitors as soon as they “came within sight of the Holy City”;3 Psalm 118 is a thanksgiving hymn with temple themes; Psalms 120 through 134 are ascension texts with themes pertaining to Zion and her temple, which may have been sung by pilgrims as they approached the temple; and Psalm 150, with its thirteen attestations of “praise,” lists the musical instruments used by temple musicians, including the trumpet, lute, harp, strings, pipe, and cymbals. In all, perhaps a total of one-third of the biblical psalms have temple themes. It is well known that during the days of the temple of Jerusalem temple priests were required to heed certain threshold laws, or gestures of approach, such as anointings, ablutions, vesting with sacred clothing, and sacrices.4 What is less known, however, is the requirement placed on temple visitors to subscribe to strict moral qualities. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

At Home Study Guide Praying the Psalms for the Week of May 15, 2016 Psalms 1-2 BETHELCHURCH Pastor Steven Dunkel

At Home Study Guide Praying the Psalms For the Week of May 15, 2016 Psalms 1-2 BETHELCHURCH Pastor Steven Dunkel Today we start a new series in the Psalms. The Psalms provide a wonderful resource of Praying the Psalms inspiration and instruction for prayer and worship of God. Ezra collected the Psalms which were written over a millennium by a number of authors including David, Asaph, Korah, Solomon, Heman, Ethan and Moses. The Psalms are organized into 5 collections (1-41, 42-72, 73-89, 90-106, and 107-150). As we read the book of Psalms we see a variety of psalms including praise, lament, messianic, pilgrim, alphabetical, wisdom, and imprecatory prayers. The Psalms help us see the importance of God’s Word (Torah) and the hopeful expectation of God’s people for Messiah (Jesus). • Why is the “law of the Lord” such an important concept in Psalm 1 for bearing fruit as a follower of Jesus? • In John 15, Jesus says that apart from Him you can do nothing. Compare the message of Psalm 1 to Jesus’ words in John 15. Where are they similar? • Psalm 2 tells of kings who think they have influence and yet God laughs at them (v. 3). Why is it important that we seek our refuge in Jesus (2:12)? • Our heart for Bethel Church in this season is that we would saturate ourselves with God’s Word, specifically the book of Psalms. We’ve created a reading plan that allows you to read a Psalm a day or several Psalms per day as well as a Proverb. -

Complex Antiphony in Psalms 121, 126 and 128: the Steady Responsa Hypothesis

502 Amzallag & Avriel: Complex Antiphony in Pss OTE 23/3 (2010), 502-518 Complex Antiphony in Psalms 121, 126 and 128: the Steady Responsa Hypothesis NISSIM AMZALLAG AND MIKHAL AVRIEL (I SRAEL ) ABSTRACT Psalms 121, 126 and 128 are three songs of Ascents displaying the same structural characteristics: (i) they include two distinct parts, each one with its own theme; (ii) the two parts have the same number of verse lines;, (iii) many grammatical and semantic similarities are found between the homolog verse lines from the two parts; (iv) a literary breakdown exists between the last verse of the first part and the first verse of the second part. These features remain unexplained as long as these poems are approached in a linear fashion. Here we test the hypothesis that these songs were performed antiphonally by two choirs, each one singing another part of the poem. This mode of complex antiphony is defined here as steady responsa. In the three songs analyzed here, the “composite text” issued from such a pairing of distant verses displays a high level of coherency, new literary properties, images and metaphors, echo patterns typical to antiphony and even “composite meanings” ignored by the linear reading. We conclude that these three psalms were originally conceived to be performed as steady responsa. A INTRODUCTION Antiphony is sometimes mentioned in the Bible. The first ceremony of alliance of the Israelites in Canaan is reported as an impressive antiphonal dialogue between two Israelite choirs: from mount Gerizim six tribes were to bless the people and from mount Eybal a responding choir of the other six tribes were to sing a hymn of curse (Deut 27:11-16). -

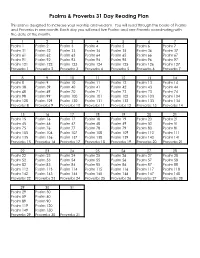

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

A Portrait of the Righteous Person

Restoration Quarterly 45.3 (2003) 151-164. Copyright © 2003 by Restoration Quarterly, cited with permission. A PORTRAIT OF THE RIGHTEOUS PERSON LES MALONEY Center for Christian Education Introduction Psalm 15 was most likely composed independently for use in a specific cultic setting as is argued by Hermann Gunkel: Ps. 15 most clearly presupposes a specific worship service. The priest communicates an answer for the laity to the question of their condition if they wish entry onto the holy mountain. However, the text does not offer a single word regarding which festival would have included this kind of question and answer.1 Gunkel challenges Mowinckel's contention that Psalm 15 is connected with the annual festival of the enthronement of Yahweh.2 While Gunkel disputes Mowinckel's assertion that this psalm's usage can be pin-pointed to a specific event on the Israelite calendar, I question the "presupposed worship service" that causes this psalm to be read as a liturgical entrance psalm. Gunkel himself says, "The response [to the question in v. 1] we think must come from the mouth of the priest."3 Could the question posed in verse 1 be a rhetorical question similar to the one asked by the prophet in Micah 6:6–7? Other rhetorical questions appear elsewhere in the first book of the Psalter (Pss. 8:5; 11:3; 27:1; 39:7). Then, what is the point? It is possible that this psalm circulated independently beyond its original setting in life, being used in situations other than the one for which it was initially composed. -

PSALM Background Notes

P a g e | 1 PSALM Background Notes As we read the Psalms together and ‘SING’ them as they should be sung a few background notes on how the Psalter is split up might be helpful 1. The Origin of the word ‘Psalm’ • The Greek word is ‘PSALMOS’ • From the Hebrew word meaning ‘to pluck’ as in what you do with a stringed instrument • Implies that the Psalms were composed to be accompanied by stringed instruments • Psalms are songs for the lyre and therefore lyric poems in the strictest sense • David and others originally wrote the Psalms to be sung with the harp 2. In NT worship we are told to sing the Psalms in our hearts. • ‘ ... singing and making melody to the Lord’ Eph 5:19 • The phrase ‘making melody’ comes from the Greek word ‘psallontes’ (literally, ‘plucking the strings of’) • Thus, we are to ‘pluck the strings of our heart’ as we sing Psalms 3. The History of the Psalms • The oldest of the Psalms originate from Moses • Exodus 15:1 to 15 – a song of triumph following the crossing of the Red Sea • Deuteronomy 32 and 33 – a song of exhortation to keep the Law after entering Canaan • Psalm 90 – a song of meditation, reflection and prayer • After Moses the writing of the Psalms had its good and bad moments • In David’s time (around BC 1000) it reached its full maturity • Under Solomon the creation of Psalms began to decline • Only twice after this did the creation of Psalms rise to any height Under Jehoshaphat in ca. -

Fr. Lazarus Moore the Septuagint Psalms in English

THE PSALTER Second printing Revised PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE DIOCESAN PRESS, MADRAS — 1971. (First edition, 1966) (Translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore) INDEX OF TITLES Psalm The Two Ways: Tree or Dust .......................................................................................... 1 The Messianic Drama: Warnings to Rulers and Nations ........................................... 2 A Psalm of David; when he fled from His Son Absalom ........................................... 3 An Evening Prayer of Trust in God............................................................................... 4 A Morning Prayer for Guidance .................................................................................... 5 A Cry in Anguish of Body and Soul.............................................................................. 6 God the Just Judge Strong and Patient.......................................................................... 7 The Greatness of God and His Love for Men............................................................... 8 Call to Make God Known to the Nations ..................................................................... 9 An Act of Trust ............................................................................................................... 10 The Safety of the Poor and Needy ............................................................................... 11 My Heart Rejoices in Thy Salvation ............................................................................ 12 Unbelief Leads to Universal -

Week Three Praising God Psalms of Praise and Thanksgiving

Week Three Praising God Psalms of Praise and Thanksgiving Preliminary Remarks Last week we discussed a group of psalms called communal and individual laments. This week we investigate psalms of praise and thanksgiving. It may seem that these two kinds of psalms are so different that they have little in common, but in fact, they need each other. Psalms of lament lead to praise and thanksgiving, and psalms of praise and thanksgiving occur after we have experienced God’s mercy and salvation. While we know how to thank God and ask God for favors, we often find it difficult to simply praise God. The psalms of praise provide us with words to praise the Lord. Psalm 8 This brief psalm is filled with wonder and awe at the beauty of creation and the role God has appointed for human beings in creation. The psalmist looks at the expanse of creation and is filled with wonder that God has such concern for human beings. This psalm reminds us of our need to care for God’s creation over which we hold the sacred duty of stewardship. Who is speaking? The church is filled with wonder at God’s creation that has found it climax in Christ. What does the Psalm say about God? God has a plan for creation in which humanity plays central role that finds its goal in Christ. Psalm 33 The psalm begins with an invitation to sing “a new song” to the Lord (vv. 1- 3) The psalm provides a first reason to sing a new song to the Lord: by the word of the Lord all things came into being (vv. -

A New English Translation of the Septuagint. 31 Psalms of Salomon

31-PsS-NETS-4.qxd 11/10/2009 10:39 PM Page 763 PSALMS OF SALOMON TO THE READER EDITION OF THE GREEK TEXT Since no critical edition of the Psalms of Salomon’s (PsSal) Greek text is available at the present time, the NETS translation is based on the edition of Alfred Rahlfs (Septuaginta. Id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interpretes, 2 vols. [Stuttgart: Württembergische Bibelanstalt, 1935]). Rahlfs’s text is, for the most part, a reprint of the edition of Oscar von Gebhardt (Die Psalmen Salomo’s zum ersten Male mit Benutzung der Athoshandschriften und des Codex Casanatensis [Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, 1895]). Rahlfs frequently incorpo- rated many of von Gebhardt’s conjectural emendations, which are referred to in Rahlfs’ text by the siglum “Gebh.” The remaining conjectural emendations included in Rahlfs’ Greek text are largely derived from the edition of Henry B. Swete (The Psalms of Solomon with the Greek Fragments of the Book of Enoch [Cam- bridge: Cambridge University Press, 1899]) and are indicated in Rahlfs’ notes by the siglum “Sw.” This book is basically a reprint of Swete’s earlier edition of the Greek text of PsSal (The Old Testament in Greek According to the Septuagint [vol. 3; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1894] 765–787), but it in- corporates readings from three new manuscripts that were included in von Gebhardt’s text. In one in- stance (17.32), Rahlfs adopted the suggestion first proposed in 1870 by A. Carrière (De Psalterio Salomo- nis disquistionem historico-criticam scripsit [Strasbourg]) that xristo_j ku/rioj, which is preserved in all of PsSal’s manuscripts, should be emended to xristo_j kuri?/ou. -

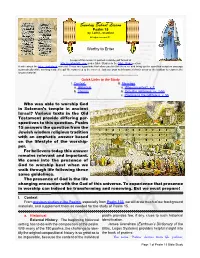

Psalm 15 by Lorin L

Sunday School Lesson Psalm 15 by Lorin L. Cranford All rights reserved © Worthy to Enter A copy of this lesson is posted in Adobe pdf format at http://cranfordville.com under Bible Studies in the Bible Study section A note about the blue, underlined material: These are hyperlinks that allow you to click them on and bring up the specified scripture passage automatically while working inside the pdf file connected to the internet. Just use your web browser’s back arrow or the taskbar to return to the lesson material. ************************************************************************** Quick Links to the Study I. Context II. Message a. Historical a. Who can enter?, v. 1 b. Literary b. Only the righteous, vv. 2-5a c. Promise to the righteous, v. 5b *************************************************************************** Who was able to worship God in Solomon’s temple in ancient Israel? Various texts in the Old Testament provide differing per- spectives to this question. Psalm 15 answers the question from the Jewish wisdom religious tradition with an emphatic answer based on the lifestyle of the worship- per. For believers today this answer remains relevant and important. We come into the presence of God to worship best when we walk through life following these same guidelines. The presence of God is the life changing encounter with the God of this universe. To experience that presence in worship can indeed be transforming and renewing. But we must prepare! I. Context From previous studies in the Psalms, especially from Psalm 133, we will draw much of our background materials, and supplement them as needed for the study of Psalm 15.