Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pusher III, L'ange De La Mort Ciné-Club Universitaire Activités Culturelles Nicolas Winding Refn Culture.Unige.Ch

Viølences - le nouveau cinéma danois Pusher III, l'ange de la mort Ciné-club universitaire Activités culturelles Nicolas Winding Refn culture.unige.ch Lundi 29 janvier 2018 à 20h | Auditorium Arditi âge légal: 16 ans Générique: DK, 2005, Coul., DVD, 104’, vo st fr Nicolas Winding Refn: Il y a une réponse très Interprétation: Zlatko Burić, Marinela Dekic, Slavko simple: je devais un million de dollars. C'est Labovic, Ilyas Agac tout. J'étais tellement endetté! Pour m'en sortir très rapidement et ne pas être hanté Milo, un trafiquant de drogue serbe, suit le reste de ma vie, je devais trouver quelque une thérapie de groupe pour soigner sa chose que je pourrais facilement financer et toxicomanie. Tandis qu’il s’occupe du banquet dont je savais qu'il aurait un attrait interna- pour les 25 ans de sa fille, il doit aussi veiller à tional. Je me suis donc forcé à retourner au ses affaires en cours. premier [Pusher] - quelque chose que j'avais toujours juré de ne jamais faire. Mais je pense Dans ce troisième volet de la trilogie, Refn joue que mon refus venait aussi de ma peur de ne avec tous les codes du genre, et passe d’un même pas pouvoir faire mieux que le premier. souffle de la comédie mélancolique au drame le plus cru et le plus abject. R.F.: En castant et en travaillant avec des crimi- nels, avez-vous vu une conscience grandissante Une entrevue de Russ Fischer avec Nicolas chez eux, au fur et à mesure que les films Winding Refn, traduction par Cerise Dumont, progressaient? membre du comité du Ciné-club universitaire N.W.R.: Les gens avec qui je travaillais avaient Pusher (1996) a commencé comme l'un des déjà cette conscience d’eux-mêmes je pense, innombrables films de truands du milieu des et ils pouvaient regarder leur vie de l'extérieur, années 90, dans le sillage de Tarantino. -

W Poszukiwaniu Duchowości Dalekiego Wschodu – Synkretyczna Wizja Filmu Only God Forgives Na Tle Twórczości Nicolasa Windinga Refna

MAREK SFUGIER W POSZUKIWANIU DUCHOWOŚCI DALEKIEGO WSCHODU – SYNKRETYCZNA WIZJA FILMU ONLY GOD FORGIVES NA TLE TWÓRCZOŚCI NICOLASA WINDINGA REFNA I jeżeli twa prawa ręka stanie ci się powodem upadku, odetnij ją i odrzuć od siebie. Bo lepiej dla ciebie, jeżeli stracisz jeden ze swych członków, niż żeby całe ciało twoje miało pójść do piekła. Kazanie na górze, Mt 5,301 Wstęp Lata 90. minionego wieku obfitowały w liczne debiuty filmowe reżyserów młodego pokolenia. Spośród nich wszystkich do niewątpliwie udanych należy zaliczyć film Pusher2 Nicolasa Windinga Refna. Urodzony w 1970 r. w Danii reżyser wpisuje się w grono twórców, którzy mimo braku wykształcenia w sztuce kinematograficznej odnieśli ogromny sukces na arenie międzynarodowej. Wyrzucony z nowojorskiej Amerykańskiej Akademii Sztuk Dramatycznych, zrezygnował z prestiżowej Duń- skiej Szkoły Filmowej, aby oddać się całkowicie realizacji wspomnianego już pełno- metrażowego debiutu. Podobnie jak Quentin Tarantino czy Kevin Smith pozostał przy tym samoukiem, działającym raczej intuicyjnie niż z wyuczonym schematy- zmem. Ważniejsze od rzemiosła okazały się pasja oraz potrzeba twórczej ekspre- sji – zaszczepione u młodego Nicolasa poprzez seanse kinowe, a także utrwalone w domowym zaciszu dzięki telewizorowi oraz kasetom wideo. Ponadto dla osoby cierpiącej na dysleksję i ślepotę barw kinematografia stanowiła w okresie dojrzewa- nia swego rodzaju audiowizualny filtr, dzięki któremu Refn doświadczał otaczającej go rzeczywistości. Szczególną fascynację znalazł zaś w amerykańskim kinie gatun- kowym, tak znienawidzonym przez matkę i ojczyma. 1 Cyt. za: Pismo Święte Nowego Testamentu, tłum. z j. greckiego S. Kowalski, Warszawa 1988, s. 23. 2 Pusher (pol. Diler), scen. N. Winding Refn i J. Dahl, reż. N. Winding Refn, Dania 1996, 105 min. -

Blanc Sur Rouge, Rien Ne Bouge... Rouge Sur Blanc, Tout Fout Le Camp !

BLANC SUR ROUGE, RIEN NE BOUGE... ROUGE SUR BLANC, TOUT FOUT LE CAMP ! DU VENDREDI 6 JANVIER AU JEUDI 1ER MARS 2012 SUR CINÉ+ FRISSON LA NOUVELLE VAGUE SCANDINAVE : POLARS GIVRÉS, HORREURS BORÉALES, ET HISTOIRES À VOUS GLACER LE SANG. En janvier et février 2012, CINE+FRISSON réinterprète à sa façon le MOIS DU BLANC. Dans la grande tradition du tout blanc pour démarrer sous les meilleurs auspices une nouvelle année, CINE+ FRISSON propose tout au long du MOIS DU BLANC un regard inédit sur les cinématographies nordiques. Venue du froid, une vague de talents scandinaves déferle depuis ces dernières années, sur l’ensemble des scènes artistiques musicales, littéraires, En ce début d’année 2012, les projecteurs sont braqués sur le Danemark cinématographiques emportant sur son passage tous les préjugés attachés qui assurera la présidence du Conseil de l’Union Européenne jusqu’en juin à la géographie de ces cultures. prochain. La Maison du Danemark dont la mission culturelle est de promouvoir De Björk à Henning Mankell, de Susanne Bier à Baltasar Kormákur, la diversité des champs artistiques et d’assurer la visibilité des artistes ces artistes ont dépassé leurs frontières, séduisant un public international. danois en France, est fière de parrainer l’initiative de la chaîne CINE+ Le signal de ce renouveau a été imprimé par le romancier Stieg Larsson, qui rend hommage à l’un des plus talentueux des cinéastes de sa génération, qui avec ses douze millions et demi de ventes dans le monde pour la trilogie notre compatriote : Nicolas Winding Refn. Millenium, a fait figure de tsunami. -

Pusher Og Svartur Á Leik Pusher Og Svartur Á Leik Pusher Og Svartur Á Leik

Hugvísindasvið Pusher og Svartur á leik En komparativ filmanalyse med fokus på beskuerens reception af virkelighedspræsentationen og den realitet filmene udspringer af Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs í dönsku Þorbjörg Erla Sigurðardóttir September 2012 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Danska Pusher og Svartur á leik En komparativ filmanalyse med fokus på beskuerens reception af virkelighedspræsentationen og den realitet filmene udspringer af Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs í dönsku Þorbjörg Erla Sigurðardóttir Kt.: 170967-4969 Leiðbeinandi: Þórhildur Oddsdóttir og Susanne Antoinette Elgum September 2012 Resumé I år havde den islandske film Svartur a leik (2012) premiere og en af den allerstørste islandske publikumsmagnet i islandsk filmhistorie. Filmen tegner et sort billede af Reykjavik’s underverden og skildrer desuden de radikale ændringer som fandt sted i den kriminelle underverden omkring årtusindeskiftet. Svartur a leik siges at være under indflydelse af Pusher (1996) som fik kæmpe succes både i Danmark og udenlands. Filmene anses for at være, hver i sit land „den første realistiske kortlægning af narkotikahandel som foregår i forbrydermiljøet“ men på hver sin måde og fra forskellig synsvinkel. Opgaven går ud på komparativ filmanalyse med hensyn til indhold, stil, miljø og samfund samt den virkelighed filmene har deres rødder og udspringer af. I den første del er der lagt vægt på baggrundsemne som knyttes til filmene, både direkte og indirekte. Dernæst kommer selve filmanalysen hvor fokussen ligger på værkanalysen eller filmens indhold og i kølvandet følger så den filmtekniske analyse. Derefter er filmene sat i et perspektiv i relation til dens virkelighed og samfundsmæssige forhold. Jeg vil endvidere se på hvilke områder filmene adskiller sig, og på hvilke områder de ligner hinanden, og i hvor høj grad vi befinder os i en realistisk verden i filmene. -

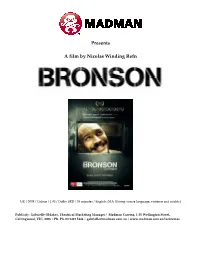

Bronson Madman0

Presents A film by Nicolas Winding Refn UK / 2008 / Colour / 1.85 / Dolby SRD / 93 minutes / English /MA (Strong coarse language, violence and nudity) Publicity: Gabrielle Oldaker, Theatrical Marketing Manager | Madman Cinema, 1-35 Wellington Street, Collingwood, VIC, 3006 | Ph. Ph. 03 9419 5444 | [email protected] | www.madman.com.au/incinemas BRONSON Press Notes…Page 2 of 24 Vertigo Films presents in association with Aramid Entertainment, Str8jacket Creations and EM Media A Vertigo Films/4DH Film Production A Film By Nicolas Winding Refn BRONSON Starring Tom Hardy Matt King James Lance Kelly Adams And Amanda Burton Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn Screenplay by Brock Norman Brock, Nicolas Winding Refn Produced by Rupert Preston Produced by Danny Hansford Director of Photography Larry Smith BSC Editor Mat Newman Co-Producer Jane Hooks 1st Assistant Director Jamie MacDermott Stunt Coordinator Julian Spencer Music Supervisor Lol Hammond Casting Director Des Hamilton Executive Producers Allan Niblo, James Richardson, Nick Love, Rob Morgan, Simon Fawcett, Suzanne Alizart, Kate Ogborn, Paul Martin, Thor Sigurjonsson BRONSON Press Notes…Page 3 of 24 ABOUT CHARLES BRONSON Born Michael Peterson in 1952, his name was changed by his fight promoter in 1987. Bronson was born in Aberystwyth in West Wales, before moving to Merseyside, and later Luton, which is often referred to as his home town. He is now 56 years of age. He was originally sentenced to 7 years in 1974 (aged 19) for a bungled armed robbery - a robbery in which no one was hurt. He has spent 34 years in prison, 30 of those years have been spent in solitary confinement. -

The Nicolas Winding Refn Handbook ‐ Everything You Need to Know

The Nicolas Winding Refn Handbook ‐ Everything You Need The Nicolas to Know about Nicolas Winding Winding Refn Handbook ‐ Refn Everything You Need to Know Emily Smith about Nicolas Winding Refn Emily Smith Nicolas Winding Refn ﴾born 29 September 1970﴿ is a Danish film director, screenwriter and producer.Winding Refn moved to the United States in 1981 and graduated from the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in 1993.He is famous for directing the Pusher trilogy. His film Drive premiered in competition at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival where it won him the Best Director Award.Winding Refn was born in Copenhagen and raised partly in New York. He is married to actress Liv Corfixen, with whom he has two children. His parents are Danish film director and editor Anders Refn and cinematographer Vibeke Winding. His half‐brother is Danish singer Kasper Winding.This book is your ultimate resource for Nicolas Winding Refn. Here you will find the most up‐to‐date information, photos, and much more.In easy to read chapters, with extensive references and links to get you to know all there is to know about his Early life, Career and Personal life right away. A quick look inside: Nicolas Winding Refn, Pusher ﴾film﴿, Bleeder ﴾film﴿, Fear X, Pusher II, Pusher 3, Bronson ﴾film﴿, Valhalla Rising .﴿film﴿, Drive ﴾2011 film﴾ New York in Bondage ‐ Primary Source Edition ﴿The New York Medical Journal, Vol. 37 : A Weekly Review of Medicine January to June, 1883, Inclusive ﴾Classic Reprint The New York Stock Exchange : A Guide to Information Sources New York Spy New Zealand Houses For Town and Country Nibiru Rising : Planet X NEW YORK WANDKALENDER 2015 DIN A2 QUER ﴿Nick Mohammed in Bits: Witness Statement ﴾BBC Radio 4: Comedy . -

DANSKE FILM I 2016

DANSKE FILM i 2016 Udarbejdet af Brancheforeningen Danske Biografer 1 Danske film i 2016 24 danske film har foreløbig fundet vej til biografernes premierekalender i 2016. Der skal tages forbehold for premieredatoer. KOLLEKTIVET (Nordisk) DK-premiere: 14/1-2016. (Drama) Hjemmeside: http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/film/da/91568.aspx?id=91568 Trailer: http://dk.filmtrailer.com/cinema/50189/kollektivet Med Ulrich Thomsen, Trine Dyrholm, Lars Ranthe og Fares Fares. Instr.: Thomas Vinterberg (”De største helte” (61.168), ”Festen” (403.642), ”It’s All About Love” (50.723), ”Dear Wendy” (14.693), ”En mand kommer hjem” (28.472), ”Submarino” (48.837), ”Jagten” (651.818) og ”Far From the Madding Crowd” (121.500)). Filmen kaster publikum ud midt-70'erne, hvor drømmen om frihed og fællesskabet er på sit højeste. I kollektivet kan man være frie og lykkelige sammen. Men da en ung elskerinde til en af beboerne flytter ind trænger virkeligheden sig på og truer med at gøre en ende på både familie, venskab og drømmen om at være sammen. Vinterbergs niende spillefilm. Baseret på teaterstykket af Mogens Rukov og instruktøren selv. Budget: kr. 33,5 mio. (4. film i Biografklub Danmark-programmet 2015/16) TORDENSKJOLD & KOLD (Filmcompagniet/SF) DK-premiere: 28/1-2016. (Drama) Hjemmeside: http://www.dfi.dk/Nyheder/FILMupdate/2014/oktober/Tordenskiold-og-hans- kammertjener.aspx Trailer: - Med Jakob Oftebro og Martin Buch. Instr.: Henrik Ruben Genz. (“En som Hodder” (146.702), “Kinamand” (26.217), “Frygtelig lykkelig” (266.795) og ”Undskyld jeg forstyrrer (85.954)). Året er 1720, freden er underskrevet, krigen er slut, og søhelten Tordenskiold aner ikke, hvad han skal stille op med sit liv. -

Filmvilág Immár E-Journal Változatban Is Előfizethető Telefax: 06-1-350-0344 E-Mail: [email protected] És Letölthető a Honlapon

FILMMŰVÉSZETI FOLYÓIRAT LIX. ÉVFOLYAM, 07. SZÁM 2016. július 490 FT / 8,60 RON www.filmvilag.hu Himnem+nonem Magyar kosztum Kinai sarkanyok 16007 CIRKO Hannes Holm: Az ember, akit Ovénak hívnak – Vertigo Média Kft. MOZI-JEGY 9 770428 387007 50% 2016 július LIX. ÉVFOLYAM 07. SZÁM MAGYAR MŰHELY Stőhr Lóránt: Széthulló kisvilágok sodrában (Tolnai Szabolcs) 4 Szalkai Réka: Belső késztetésből (Beszélgetés Tolnai Szabolccsal) 8 Hirsch Tibor: Múltunk a nyereg alatt (Magyar film, magyar idő– 3. rész) 10 MAGYAR KOSZTÜM Soós Tamás Dénes: A belső kép (Beszélgetés Nagy András operatőrrel) Keleti ellenséget – talán az Egri csillagok színpompásan fenyegető tö- Varga Zoltán: Macskaszem és párducmosoly rök harci seregszemléjét leszámítva – kosztümös filmjeink soha nem (Magyar animáció: A nyalintás nesze; Love) 16 mutatnak úgy, hogy a magyarok nem csupán az ellenség túlerejével dacolnánk, hanem azok vélt vagy valós civilizációs gőgjével is. Ilyen ösz- NŐI SZEREPEK szetett érzések magyar hősben soha nem támadnak turbános-lófarkas Vajda Judit: Párosával a pokolba (Kelly Reichardt) 18 ellenséggel szemben, viszont rizsporos-parókás, háromszög-kalapossal Pernecker Dávid: A nő is ember (Paul Feig hősnői) 22 szemben szinte bármikor. Tüske Zsuzsanna: Nők a keverőpult mögött (Jodie Foster: Pénzes cápa) 25 Bán Frigyes: Rákóczi hadnagya (1953) – 10. oldal MACSÓ MÍTOLÓGIA Szabó Ádám: Istenek hajnala (Nicolas Winding Refn és a heroizmus) 26 Dunai Tamás: Comic noir (Shane Black buddy-filmjei) 29 KÍNAI SÁRKÁNYOK Vincze Teréz: Tér, idő, nosztalgia (Tsai Ming-liang meditációi) 32 Varró Attila: Égi törzsek (Új kínai film) 35 Baski Sándor: Beszivárog a valóság (Udine) 38 FESZTIVÁL Gyenge Zsolt: Szalmaláng vagy erdőtűz? (Cannes) 40 Buglya Zsófia: Önismereti leckék (Graz/Linz) 44 FILMZENE Géczi Zoltán: A herceg hagyatéka (Prince 1958-2016) 46 KELLY REICHARDT VIDEÓJÁTÉK Kelly Reichardt hősei frusztrációt mindig úgy oldják fel, hogy a másik Herpai Gergely: Orkazmus a multiplexen (Duncan Jones:Warcraft) 48 ember ellen fordulnak. -

Race, Ethnicity and Gang Violence: Exploring Multicultural Tensions in Contemporary

1 Race, Ethnicity and Gang Violence: Exploring Multicultural Tensions in Contemporary Danish Cinema Kate Moffat, University of Stirling Accepted for publication in Scandinavian-Canadian Studies published by the Association for the Advancement of Scandinavian Studies in Canada. Biography Kate Moffat is a PhD candidate at the University of Stirling where her research focuses on race and ethnicity in contemporary Nordic film culture. Her interests also extend to the film practices of the indigenous Sámi people. She has published work on both areas in Finnish and English in journals such as Lähikuva and the Journal of Scandinavian Cinema. Abstract: One of the most striking genre conventions to emerge in Danish cinema in recent years is the gangster motif. Replete with gritty social realism, urban decay, and tribal warfare between different ethnic groups these films reflect a growing discontent in the Danish welfare state, particularly regarding multiculturalism and inclusion. I follow these trends from the mid-1990s, focusing specifically on the themes of ethnic division in several key texts. These include Michael Noer and Tobias Lindholm’s R [R: Hit First, Hit Hardest] (2010), Michael Noer’s Nordvest [Northwest] (2013) and Omar Shargawi’s Gå med fred, Jamil [Go With Peace, Jamil] (2008). I explore racial division in these films by examining how they reflect or subvert cultural and political approaches towards diversity in Denmark over the last two decades. Keywords: Danish cinema, gangster genre, multiculturalism, immigration, welfare state 2 Introduction: Nordic Genre Cinema and the Medium Concept Film Themes of race and ethnicity became increasingly prevalent in Danish cinema from the mid- 1990s onwards. -

Klik Her for at Se Nyhedskatalog 2011-2012 (Pdf, 3 M)

Data: 3355 mmmm 2011-2012 NyhedskatalogNyhedskatalog DANSKE BØRNE- OG UNGDOMSFILMKLUBBER Forord 2011 ................................................................................................ 3 An Education .............................................................................................. 4 Beslutningen ............................................................................................... 5 Den Kæmpestore Bjørn ............................................................................... 6 Dragejægerne ............................................................................................. 7 Easy A ........................................................................................................ 8 Fantastic Mr. Fox ......................................................................................... 9 Fish Tank ..................................................................................................... 10 Grusomme mig ........................................................................................... 11 Hold om mig .............................................................................................. 12 Hævnen ...................................................................................................... 13 Ingen forbindelse ........................................................................................ 14 Karate Kid .................................................................................................. 15 Karla og Jonas ........................................................................................... -

Race, Ethnicity, and Gang Violence: Exploring Multicultural Tensions in Contemporary Danish Cinema

Race, Ethnicity, and Gang Violence: Exploring Multicultural Tensions in Contemporary Danish Cinema KATE MOFFAT ABSTRACT: One of the most striking genre conventions to emerge in Danish cinema in recent years is the gangster motif. Replete with gritty social realism, urban decay, and tribal warfare between different ethnic groups, these films reflect a growing discontent in the Danish welfare state, particularly regarding multiculturalism and inclusion. This article follows these trends from the mid-1990s, focusing specifically on the themes of ethnic division in four films: Nicolas Winding Refn’s Pusher (1996), Michael Noer’s Nordvest (2013) [Northwest], Omar Shargawi’s Gå med fred, Jamil (2008) [Go With Peace, Jamil], and Michael Noer and Tobias Lindholm’s R (2010) [R: Hit First, Hit Hardest]. The article explores racial division in these films by examining how they reflect or subvert cultural and political approaches towards diversity in Denmark over the last two decades. RÉSUMÉ : L’une des conventions de genre les plus frappantes à avoir émergée dans le cinéma danois ces dernières années est le genre gangster. Remplis de réalisme social audacieux, de déclin urbain et de guerres tribales entre différents groupes ethniques, ces films reflètent un mécontentement croissant envers l’État-providence danois, en particulier en ce qui concerne le multiculturalisme et l’inclusion. Cet article suit ces tendances depuis le milieu des années 1990, en se concentrant spécifiquement sur les thèmes du clivage ethnique dans quatre films: Pusher de Nicolas Winding Refn (1996), Nordvest [Northwest, en français : Nord-Ouest] (2013) de Michael Noer, Gå med fred, Jamil d’Omar Shargawi [Go With Peace, Jamil, en français : Va en paix, Jamil] (2008), et R de Michael Noer et Tobias Lindholm (2010). -

The Neon Demon Titolo Originale: Id

The Neon Demon Titolo originale: Id. Regia: Nicolas Winding Refn Sceneggiatura: Nicolas Winding Refn, Mary Laws, Polly Stenham Fotografia: Natasha Braier Montaggio: Matthew Newman Musica: Cliff Martinez Scenografia: Elliott Hostetter Interpreti: Elle Fanning (Jesse), Abbey Lee (Sarah), Desmond Harrington (Jack), Christina Hendricks (Roberta Hoffman), Keanu Reeves (Hank), Jena Malone (Ruby), Bella Heathcote (Gigi) Produzione: Nicolas Winding Refn, Lene Børglum, Sidonie Dumas, Vincent Maraval per Space Rocket Nation / Gaumont / Wild Bunch / Vendian Entertainment / Bold Films Distribuzione: Koch Media / Italian International Film / Midnight Factory Durata: 117' Origine: Francia / USA / Danimarca, 2016 Nicolas Winding Refn: “Non sono il miglior regista del mondo, sono solo il migliore nel fare il tipo di film che faccio” Nicolas Winding Refn è un regista fuori dagli schemi, un autore istintivo e autodidatta che ha avuto un percorso pieno di sali e scendi arrivando all'elaborazione di uno stile personale, perfettamente riconoscibile. Classe 1970, originario di Copenaghen, figlio d'arte, vive la sua infanzia e adolescenza a New York, dove frequenta con alterne fortune l'American Academy of Dramatic Arts. Rientrato nella natia Danimarca, decide di abbandonare la scuola di cinema per impegnarsi in un progetto ambizioso: trasformare in lungometraggio un suo corto realizzato per una piccola emittente televisiva. Da questo presupposto nasce Pusher (1996), primo capitolo di una trilogia di culto che presenta in nuce gran parte delle tematiche che caratterizzeranno il suo cinema. Un esordio folgorante che lo pone immediatamente tra i registi più interessanti della sua generazione. Con il suo secondo film, Bleeder (1999), Refn prosegue nel discorso di rappresentazione dell'indissolubile legame tra amore e morte, tornando a raccontare la vita di personaggi ai margini della società.