Cycling in the City Regions Delivering a Step Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pennine Cycleway Pennine Health Benefits of Cycling of Benefits Health Commuting Cycle

Springwood Rd). Another fast descent into the beautiful parkland brings parkland beautiful the into descent fast Another Rd). Springwood watch out for a sign turning you left down into Towneley Park (via Park Towneley into down left you turning sign a for out watch As you come into the first section on the road with houses on both sides, both on houses with road the on section first the into come you As and follow the road towards the Pike Hill area of south-east Burnley. Burnley. south-east of area Hill Pike the towards road the follow and village of Mereclough (take care on the descent). Turn right into Red Lees Rd Lees Red into right Turn descent). the on care (take Mereclough of village The Cycleway continues along the road as it drops steeply down past the past down steeply drops it as road the along continues Cycleway The distinctive shape of Pendle Hill. Hill. Pendle of shape distinctive excellent views over the surrounding countryside and across to the to across and countryside surrounding the over views excellent was used as a packhorse trail by merchants carrying woollen cloth. It offers It cloth. woollen carrying merchants by trail packhorse a as used was The Causeway dates back several centuries to when it when to centuries several back dates Causeway The past the wind farm. wind the past Bronte sisters - Withins, Stanbury and Haworth. and Stanbury Withins, - sisters Bronte The route enters Lancashire from Hebden Bridge via the Long Causeway Long the via Bridge Hebden from Lancashire enters route The east) the moor reaches across to the brooding places made famous by the by famous made places brooding the to across reaches moor the east) From Hebden Bridge via Burnley to Lake Burwain Lake to Burnley via Bridge Hebden From by a quiet attractive road at the top of Widdop Moor. -

Summary of Outcomes of the Cycling Demonstration Towns and Cycling City and Towns Programmes

Summary of Outcomes of the Cycling Demonstration Towns and Cycling City and Towns Programmes Lynn Sloman, Andy Cope, Angela Kennedy, Fiona Crawford, Nick Cavill and John Parkin Report to the Department for Transport April 2017 The preferred citation for this paper is: Sloman L, Cope A, Kennedy A, Crawford F, Cavill N and Parkin J (2017) Summary of outcomes of the Cycling Demonstration Towns and Cycling City and Towns programmes This report was written by Transport for Quality of Life, based on analysis carried out by Sustrans Research and Monitoring Unit with Cavill Associates and University of the West of England, Bristol. www.transportforqualityoflife.com www.sustrans.org.uk www.cavill.net www.uwe.ac.uk Acknowledgements The authors are grateful for the extensive assistance of officers in the six Cycling Demonstration Towns and 12 Cycling City and Towns in providing monitoring data for this research. We are also grateful for additional support provided by Lisa Muller, Katie Pullen, George Macklon, Katie Thomson, James O’Hare, Richard Sanders, Alison Janes, Hannah Delaney, Laurence Bonner, Peter Stephenson, Charlotte Draycott and Jo Watson. Disclaimer Although this report was commissioned by the Department for Transport (DfT), the recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the DfT. While every effort has been made to ensure the information in this document is accurate, DfT does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of that information; and it cannot accept liability for any loss or damages of any kind resulting from reliance on the information or guidance this document contains. -

Cycling Finding Your

Good Cycling Code Check list: Further information Cycling ✖ Do not cycle on the pavement unless it is ✔ Use designated cycle routes where possible. Other leaflets in this series: specifically designated as a shared use path Elsewhere choose quiet, minor roads avoiding major Cycling: the right bike for you finding your way (one for cyclists and walkers, and in some cases junctions. Cycling: basic bike maintenance wheelchair users or horse riders). ✔ Use the wide range of resources available to plan Cycling: in different conditions Cycling: security matters ✔ Do give way to pedestrians and other path your route. Cycling: sharing your route users when on a shared use path Useful contacts Cycling: with children ✔ Do obey the Highway Code when cycling on Sustrans Information Service tel: 0117 929 0888 or Cycling: clothes & accessories the road. www.sustrans.org.uk A full version of the ‘Good Cycling Code’ is For more copies of this leaflet or others in the series, available from Sustrans The CTC (Cyclists Touring Club) is another useful or for advice on where to cycle, including maps and resource for cyclists, offering route advice, cycle guides, contact Sustrans on 0117 929 0888 or visit www.sustrans.org.uk Maps and other resources campaigning, and third party insurance, among other benefits. See www.ctc.org.uk or call 01483 417217 for There is a huge range of maps and guides available details. Acknowledgements for cyclists. Sustrans and Bristol City Council would like to thank You may have a local cycle campaign group, who could the Government of Western Australia for guidance on Free maps be an excellent source of help and advice. -

Cardiff Making Tracks Our Vision for Cycling in Cardiff

2019 Cardiff Making tracks Our vision for cycling in Cardiff Cardiff has made a lot of However, there is still much more to do to progress over the last two meet the challenges of the climate emergency, years as we have made congestion and poor air quality in a rapidly a start on our ambitious growing city. We launched our 10-year vision programme to develop for transport in January 2020, which lays out cycling infrastructure fit an ambitious plan to revolutionise transport for the 21st century city. options in Cardiff and the region. The implementation of five We have doubled the proportion of people new Cycleway routes connecting communities cycling to work over the last 10 years and to key destinations across the city is now are proposing to double this again by 2030. underway, with the first section of Cycleway 1 In order to achieve this, we will complete a on St Andrew’s Place and Senghennydd Road high-quality, safe and fully segregated cycle now completed. network by 2026, expand our successful Nextbike scheme, support schools to develop We are also improving important existing active travel plans to promote walking, scooting routes, including the Taff Trail. This has and cycling to school, and introduce a ‘Streets included the creation of Wales’ first “bicycle for Health Initiative’ to reclaim our streets as street” as part of the landmark Greener healthy spaces for everyone to enjoy. Grangetown scheme. We also want to make Cardiff a 20mph city, The take up of the Nextbike on-street cycle to normalise slower speeds and help make hire scheme has exceeded all expectations on-road cycling safer. -

Disabled People and the National Cycle Network

This information sheet is also available in large type. INFORMATION SHEET FF05 JUNE 1998 Disabled people and the National Cycle Network 1 Introduction Over 6 million people in Britain have some form of disability (1) and they often find themselves excluded from the activities that other people take for granted because their needs have not been addressed at the planning stages of key projects. In partnership with Sustrans, Local Authorities and other organisations all over the UK are developing the National Cycle Network which we believe will bring a whole range of benefits to many disabled people. This document addresses issues Smedley Toby relating to its use by disabled people. Traffic free routes benefit walkers and cyclists of all abilities and wheelchair users. We know that there are genuine concerns voiced by different users, and cyclists of all abilities and including disabled people, about wheelchair users. The routes which Definitions (3) shared use, and this document are likely to be most attractive are Where disability is referred to in this should be read in conjunction with newly constructed shared use paths information sheet, we mean: Sustrans’ Information Sheet and upgraded paths, which are Any restriction or limitation, resulting Shared Use Routes (2). described below. from an impairment, of ability to perform an activity within the range considered standard for a human being. 2 National Cycle 3 New paths Where disabled people are referred to, Network we mean: For over fifteen years, Sustrans has People who - use wheelchairs and specialised cycles been building paths free from motor - walk with difficulty, including those The National Cycle Network will be a traffic largely on disused railways with a psychological loss of function UK-wide 8,000 mile network of safe, and canal towpaths. -

Making a Cycling Town: Compilation

Making a Cycling Town: a compilation of practitioners’ experiences from the Cycling Demonstration Towns programme Qualitative Survey 2005-2009 Contents Abbreviations & Glossary 5 Introduction 6 Acknowledgements 7 Chapter 1: ‘Lift Off’ for Cycling 9 Bikeability 13 Chapter 2: Cycling Programme Delivery Best Practice 15 Chapter 3: Cycling Demonstration Town Stories 27 Aylesbury 28 Brighton & Hove 34 Darlington 40 Derby 46 Exeter 52 Lancaster with Morecambe 58 Chapter 4: Common Elements of the Programmes 65 Infrastructure 66 Marketing and Enabling Cycling 72 Schools and Bikeability 79 Workplaces 86 2 Figures and Tables Figure 2.1: Average Proportion of Budget Spent by Measure 21 Figure 3.1: Aylesbury Programme Summary 28 Figure 3.2: Brighton & Hove Programme Summary 34 Figure 3.3: Darlington Programme Summary 40 Figure 3.4: Derby Programme Summary 46 Figure 3.5: Exeter Programme Summary 52 Figure 3.6: Lancaster with Morecambe Programme Summary 58 Figure 4.1: Marketing Channels & Tools Used by the Cycling Demonstration Towns 73 Figure 4.2: Bikeability and Bike It Participation by Cycling Demonstration Town 79 Table 2.1: Average Staff Time Invested by Measure 18 Table 4.1: Investment in Infrastructure 71 Table 4.2: CDT Information Resources & Distribution Channels 72 Table 4.3: Investment in Marketing and Enabling Cycling Initiatives 77 Table 4.4: Investment in Cycling Promotion at Schools 84 Table 4.5: Investment in Cycling Promotion at Workplaces 89 Box 2.1: Examples of Internal Teams Supporting CDT Delivery 19 Box 2.2: Examples of External -

Swansea Sustainability Trail a Trail of Community Projects That Demonstrate Different Aspects of Sustainability in Practical, Interesting and Inspiring Ways

Swansea Sustainability Trail A Trail of community projects that demonstrate different aspects of sustainability in practical, interesting and inspiring ways. The On The Trail Guide contains details of all the locations on the Trail, but is also packed full of useful, realistic and easy steps to help you become more sustainable. Pick up a copy or download it from www.sustainableswansea.net There is also a curriculum based guide for schools to show how visits and activities on the Trail can be an invaluable educational resource. Trail sites are shown on the Green Map using this icon: Special group visits can be organised and supported by Sustainable Swansea staff, and for a limited time, funding is available to help cover transport costs. Please call 01792 480200 or visit the website for more information. Watch out for Trail Blazers; fun and educational activities for children, on the Trail during the school holidays. Reproduced from the Ordnance Survey Digital Map with the permission of the Controller of H.M.S.O. Crown Copyright - City & County of Swansea • Dinas a Sir Abertawe - Licence No. 100023509. 16855-07 CG Designed at Designprint 01792 544200 To receive this information in an alternative format, please contact 01792 480200 Green Map Icons © Modern World Design 1996-2005. All rights reserved. Disclaimer Swansea Environmental Forum makes makes no warranties, expressed or implied, regarding errors or omissions and assumes no legal liability or responsibility related to the use of the information on this map. Energy 21 The Pines Country Club - Treboeth 22 Tir John Civic Amenity Site - St. Thomas 1 Energy Efficiency Advice Centre -13 Craddock Street, Swansea. -

Paths for Everyone National Cycle Network Physical Review and Action Plan South of England

Paths for everyone National Cycle Network physical review and action plan South of England 1 Contents 1. Introduction to the National Cycle Network 3 A vision for a traffic-free Network 3 Physical review and action plans 5 Network development plans 5 Design principles for the National Cycle Network 5 2. Overview of the Network in the South of England 6 Condition of the Network – results of the Network audit 7 Identifying the issues 7 3. Strategic priorities for the South of England 8 Improving the existing routes 8 Creating new routes 8 De-designation of routes 8 4. Quantifying the ambition for the South of England 9 Closing the gap to Very Good 9 Closing the gap to Good 10 5. UK-wide priorities 11 Accessibility 11 Signage 11 6. Activation projects 12 Identification process 12 Activation projects for the South of England 13 Activation projects map 15 7. Conclusion 16 Acknowledgements 16 Sustrans is the charity making it easier for people to walk and cycle. We connect people and places, create liveable neighbourhoods, transform the school run and deliver a happier, healthier commute. Join us on our journey. www.sustrans.org.uk Sustrans is a registered charity no. 326550 (England and Wales) SC039263 (Scotland). © Sustrans November 2018 2 1. Introduction to the National Cycle Network The National Cycle Network is a 23-year-old network of 16,575 Key miles of signed routes spanning the UK. It is used by walkers, On-road route joggers, wheelchair users and horse riders, as well as people Traffic-free route on bikes. -

Sustrans Design Manual Chapter 9 Cycle and Rail Integration (Draft)

Sustrans Design Manual • Chapter 9: Cycle and rail integration (2014, draft) Sustrans Design Manual Chapter 9 Cycle and Rail Integration (draft) December 2014 December 2014 1 Sustrans Design Manual • Chapter 9: Cycle and rail integration (2014, draft) About Sustrans Contents Sustrans makes smarter travel choices This chapter of the Sustrans Design Manual should be read in possible, desirable and inevitable. We’re conjunction with Chapter 1 “Principles and processes for cycle friendly a leading UK charity enabling people to design.” That chapter includes key guidance on core design principles, travel by foot, bike or public transport whether to integrate with or segregate from motor traffic, the space for more of the journeys we make every required by cyclists and other road users as well as geometrical day. We work with families, communities, considerations. Readers are also directed towards the “Handbook for policy-makers and partner organisations cycle-friendly design” which contains a concise illustrated compendium so that people are able to choose of the technical guidance contained in the Design Manual. This chapter healthier, cleaner and cheaper journeys, has initially been issued as a draft and it is intended that it be reviewed with better places and spaces to move during 2015; feedback on the content is invited and should be made by through and live in. 31 May 2015 to [email protected] It’s time we all began making smarter travel choices. Make your move and 1. Key principles support Sustrans today. www.sustrans. 2. Introduction org.uk 3. Travelling to the station Head Office 4. Routes into and within the station Sustrans 2 Cathedral Square 5. -

'What Works' Review of Evidence from Cycling and Walking Schemes

1 Making the economic case for active travel Active travel and economic performance: A ‘What Works’ review of evidence from cycling and walking schemes Active Travel Toolkit Slide Pack Active travel and economic performance: A ‘What Works’ review of evidence from cycling and walking schemes. Part of the Active Travel Toolbox, written by Sustrans with support from Dr Adrian Davis, Living Streets and The July 2017 TAS Partnership. Sustrans is a registered charity no. 326550 (England and Wales) SCO39263 (Scotland). 2 What is this slide pack for? This slide pack provides a summary of the toolkit: Active travel and economic performance. The Active Travel Toolbox slide packs are designed to demonstrate the benefits of sustainable transport and help LEPs and local delivery partners strategically invest in walking and cycling schemes. This slide pack provides: • Key messages • Statistics and evidence 3 Contents This slide pack covers: • The contribution of walking and cycling to economic performance. • What works? Walking and cycling intervention typologies. • Where to target interventions. • Applying a holistic approach. 4 Key messages • There is increasing, and increasingly strong, evidence that walking and cycling can play a very significant role in optimising the contribution of transport to economic performance • There are a range of intervention types that can be effective in increasing walking and cycling • The nature of economic benefits gained varies between rural and urban settings • An optimum balance between capital and revenue investment -

Doncaster to Conisbrough (PDF)

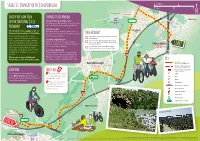

Kilometres 0 Miles 0.5 1 1.5 0 Kilometres 1 Stage 17: Doncaster to Conisbrough A638 0 Miles 0.5 1 Cusworth To Selby River Don Enjoy the Slow Tour Things to see and do Wheatley Cusworth Hall and Museum A Cusworth 19 on the National Cycle An imposing 18th century country house Hall set in extensive landscaped parklands. 30 Network! A6 Sprotborough A638 Richmond The Slow Tour is a guide to 21 of Sprotborough is a village which sits on Hill the best cycle routes in Yorkshire. the River Don and has locks which allow Take a Break! It’s been inspired by the Tour de boats to pass safely. Doncaster has plenty of cafés, pubs and restaurants. France Grand Départ in Yorkshire in A 1 Conisbrough Viaduct (M Doncaster ) 2014 and funded by Public Health The Boat Inn, Sprotborough does great A630 With its 21 arches the grand viaduct Teams in the region. All routes form food and is where Sir Walter Scott wrote spans the River Don and formed part of his novel Ivanhoe. Doncaster part of the National Cycle Network - start the Dearne Valley Railway. The Red Lion, Conisbrough is a Sam more than 14,000 miles of traffic- Smith pub and serves a range of food. River Don free paths, quiet lanes and on-road Conisbrough Castle A638 walking and cycling routes across This medieval fortification was initially the UK. built in the 11th century by William de Hyde Warenne, the Earl of Surrey, after the Park This route is part of National Hexthorpe A18 0 Norman conquest of England in 1066. -

National Cycle Route 45 20 Miles • 32 Km

45 National Cycle Route 45 20 Miles • 32 km Code of Conduct ı Always follow the Highway code ı Be considerate to other users, and give way to pedestrians and horse riders ı Take particular care at junctions, when cycling downhill and on loose surfaces ı Ride in single file on narrow or busy roads ı Consider wearing a helmet and high visibility clothing ı Fit a bell and use it, don’t surprise people ı Railways – only cross the railway line at permitted level crossings, obey the safety warning signs and look and listen before crossing ı Motorbikes are not permitted on the off-road paths ı Cars – if you need to bring your car, please park only in designated car parks ı Horse-riders, for their own safety, are not permitted along the path adjacent to the Severn Valley Railway ©Rosemary Winnall Leaflet Ref. No: NCN1A No: Ref. Leaflet Designed by Salisbury SHROPSHIRE MA Creative Stonehenge • www.macreative.co.uk • •www.macreative.co.uk Development Fund Development European Regional European Marlborough by the European Union European the by Project Part-Financed Project 0845 113 0065 113 0845 wiltshire.gov.uk matthewhoskins@ Sustrans Sustrans % 01225 713481 01225 www.sustrans.org.uk www.sustrans.org.uk Swindon County Council County Wiltshire by the charity Sustrans. charity the by Map artworkbythe one of the award-winning projects coordinated coordinated projects award-winning the of one This route is part of the National Cycle Network, Network, Cycle National the of part is route This Cirencester gov.uk National Cycle Network Cycle National www.gloucestershire.