Murder and Mattering in Harambe's House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Recent Developments in the Study of Wild Chimpanzee Behavior

Evolutionary Anthropology 9 ARTICLES Recent Developments in the Study of Wild Chimpanzee Behavior JOHN C. MITANI, DAVID P. WATTS, AND MARTIN N. MULLER Chimpanzees have always been of special interest to anthropologists. As our organization, genetics and behavior, closest living relatives,1–3 they provide the standard against which to assess hunting and meat-eating, inter-group human uniqueness and information regarding the changes that must have oc- relationships, and behavioral endocri- curred during the course of human evolution. Given these circumstances, it is not nology. Our treatment is selective, and surprising that chimpanzees have been studied intensively in the wild. Jane Good- we explicitly avoid comment on inter- all4,5 initiated the first long-term field study of chimpanzee behavior at the Gombe population variation in behavior as it National Park, Tanzania. Her observations of tool manufacture and use, hunting, relates to the question of chimpanzee and meat-eating forever changed the way we define humans. Field research on cultures. Excellent reviews of this chimpanzee behavior by Toshisada Nishida and colleagues6 at the nearby Mahale topic, of central concern to anthropol- Mountains National Park has had an equally significant impact. It was Nishida7,8 ogists, can be found elsewhere.12–14 who first provided a comprehensive picture of the chimpanzee social system, including group structure and dispersal. SOCIAL ORGANIZATION No single issue in the study of wild Two generations of researchers erything about the behavior of these chimpanzee behavior has seen more have followed Goodall and Nishida apes in nature. But this is not the case. debate than the nature of their social into the field. -

Gorilla Beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26

Gorilla beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia ChordataMammaliaPrimatesHominidae Scientific Gorilla beringei Name: Species Matschie, 1903 Authority: Infra- specific See Gorilla beringei ssp. beringei Taxa See Gorilla beringei ssp. graueri Assessed: Common Name(s): English –Eastern Gorilla French –Gorille de l'Est Spanish–Gorilla Oriental TaxonomicMittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B. and Wilson D.E. 2013. Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Volume Source(s): 3 Primates. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. This species appeared in the 1996 Red List as a subspecies of Gorilla gorilla. Since 2001, the Eastern Taxonomic Gorilla has been considered a separate species (Gorilla beringei) with two subspecies: Grauer’s Gorilla Notes: (Gorilla beringei graueri) and the Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) following Groves (2001). Assessment Information [top] Red List Category & Criteria: Critically Endangered A4bcd ver 3.1 Year Published: 2016 Date Assessed: 2016-04-01 Assessor(s): Plumptre, A., Robbins, M. & Williamson, E.A. Reviewer(s): Mittermeier, R.A. & Rylands, A.B. Contributor(s): Butynski, T.M. & Gray, M. Justification: Eastern Gorillas (Gorilla beringei) live in the mountainous forests of eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, northwest Rwanda and southwest Uganda. This region was the epicentre of Africa's "world war", to which Gorillas have also fallen victim. The Mountain Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei beringei), has been listed as Critically Endangered since 1996. Although a drastic reduction of the Grauer’s Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei graueri), has long been suspected, quantitative evidence of the decline has been lacking (Robbins and Williamson 2008). During the past 20 years, Grauer’s Gorillas have been severely affected by human activities, most notably poaching for bushmeat associated with artisanal mining camps and for commercial trade (Plumptre et al. -

Combined June

TABLE OF CONTENTS Tuesday, June 2, 2020 Geoffrey Burkhart Biography ............................................................................................. 2 Geoffrey Burkhart Testimony .......................................................................................... 3-7 Geoffrey Burkhart Attachment 1 ................................................................................... 8-32 Geoffrey Burkhart Attachment 2 ................................................................................. 33-55 Douglas Wilson Biography ............................................................................................... 56 Douglas Wilson Testimony.......................................................................................... 57-62 Douglas Wilson Attachment 1 ..................................................................................... 63-75 Douglas Wilson Attachment 2 ..................................................................................... 76-78 Douglas Wilson Attachment 3 ..................................................................................... 79-81 Carlos Martinez Biography ............................................................................................... 82 Carlos Martinez Testimony.......................................................................................... 83-87 Carlos Martinez Attachment ...................................................................................... 88-184 Mark Stephens Biography.............................................................................................. -

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid University of Sheffield - NFCA Contents Poster - 178R472 Business Records - 178H24 412 Maps, Plans and Charts - 178M16 413 Programmes - 178K43 414 Bibliographies and Catalogues - 178J9 564 Proclamations - 178S5 565 Handbills - 178T40 565 Obituaries, Births, Death and Marriage Certificates - 178Q6 585 Newspaper Cuttings and Scrapbooks - 178G21 585 Correspondence - 178F31 602 Photographs and Postcards - 178C108 604 Original Artwork - 178V11 608 Various - 178Z50 622 Monographs, Articles, Manuscripts and Research Material - 178B30633 Films - 178D13 640 Trade and Advertising Material - 178I22 649 Calendars and Almanacs - 178N5 655 1 Poster - 178R47 178R47.1 poster 30 November 1867 Birmingham, Saturday November 30th 1867, Monday 2 December and during the week Cattle and Dog Shows, Miss Adah Isaacs Menken, Paris & Back for £5, Mazeppa’s, equestrian act, Programme of Scenery and incidents, Sarah’s Young Man, Black type on off white background, Printed at the Theatre Royal Printing Office, Birmingham, 253mm x 753mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.2 poster 1838 Madame Albertazzi, Mdlle. H. Elsler, Mr. Ducrow, Double stud of horses, Mr. Van Amburgh, animal trainer Grieve’s New Scenery, Charlemagne or the Fete of the Forest, Black type on off white backgound, W. Wright Printer, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 205mm x 335mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.3 poster 19 October 1885 Berlin, Eln Mexikanermanöver, Mr. Charles Ducos, Horaz und Merkur, Mr. A. Wells, equestrian act, C. Godiewsky, clown, Borax, Mlle. Aguimoff, Das 3 fache Reck, gymnastics, Mlle. Anna Ducos, Damen-Jokey-Rennen, Kohinor, Mme. Bradbury, Adgar, 2 Black type on off white background with decorative border, Druck von H. G. -

Conflict and Cooperation in Wild Chimpanzees

ADVANCES IN THE STUDY OF BEHAVIOR VOL. 35 Conflict and Cooperation in Wild Chimpanzees MARTIN N. MULLER* and JOHN C. MITANIt *DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BOSTON UNIVERSITY BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, 02215, USA tDEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN, 48109, USA 1. INTRODUCTION The twin themes of competition and cooperation have been the focus of many studies in animal behavior (Alcock, 2001; Dugatkin, 2004; Krebs and Davies, 1997). Competition receives prominent attention because it forms the basis for the unifying, organizing principle of biology. Darwin's (1859) theory of natural selection furnishes a powerful framework to understand the origin and maintenance of organic and behavioral diversity. Because the process of natural selection depends on reproductive competition, aggression, dominance, and competition for mates serve as important foci of ethological research. In contrast, cooperation in animals is less easily explained within a Darwinian framework. Why do animals cooperate and behave in ways that benefit others? Supplements to the theory of natural selection in the form of kin selection, reciprocal altruism, and mutualism provide mechanisms that transform the study of cooperative behavior in animals into a mode of inquiry compatible with our current understand- ing of the evolutionary process (Clutton-Brock, 2002; Hamilton, 1964; Trivers, 1971). If cooperation can be analyzed via natural selection operating on indivi- duals, a new way to conceptualize the process emerges. Instead of viewing cooperation as distinct from competition, it becomes productive to regard them together. Students of animal behavior have long recognized that an artificial dichotomy may exist insofar as animals frequently cooperate to compete with conspecifics. -

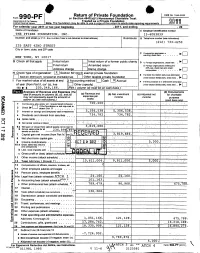

Return of Private Foundation CT' 10 201Z '

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirem M11 For calendar year 20 11 or tax year beainnina . 2011. and ending . 20 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number THE PFIZER FOUNDATION, INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (212) 733-4250 235 EAST 42ND STREET City or town, state, and ZIP code q C If exemption application is ► pending, check here • • • • • . NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D q 1 . Foreign organizations , check here . ► Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address chang e Name change computation . 10. H Check type of organization' X Section 501( exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation q 19 under section 507(b )( 1)(A) , check here . ► Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col (c), line Other ( specify ) ---- -- ------ ---------- under section 507(b)(1)(B),check here , q 205, 8, 166. 16) ► $ 04 (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (The (d) Disbursements total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for charitable may not necessanly equal the amounts in expenses per income income Y books purposes C^7 column (a) (see instructions) .) (cash basis only) I Contribution s odt s, grants etc. -

ASEBL Journal

January 2019 Volume 14, Issue 1 ASEBL Journal Association for the Study of EDITOR (Ethical Behavior)•(Evolutionary Biology) in Literature St. Francis College, Brooklyn Heights, N.Y. Gregory F. Tague, Ph.D. ▬ ~ GUEST CO-EDITOR ISSUE ON GREAT APE PERSONHOOD Christine Webb, Ph.D. ~ (To Navigate to Articles, Click on Author’s Last Name) EDITORIAL BOARD — Divya Bhatnagar, Ph.D. FROM THE EDITORS, pg. 2 Kristy Biolsi, Ph.D. ACADEMIC ESSAY Alison Dell, Ph.D. † Shawn Thompson, “Supporting Ape Rights: Tom Dolack, Ph.D Finding the Right Fit Between Science and the Law.” pg. 3 Wendy Galgan, Ph.D. COMMENTS Joe Keener, Ph.D. † Gary L. Shapiro, pg. 25 † Nicolas Delon, pg. 26 Eric Luttrell, Ph.D. † Elise Huchard, pg. 30 † Zipporah Weisberg, pg. 33 Riza Öztürk, Ph.D. † Carlo Alvaro, pg. 36 Eric Platt, Ph.D. † Peter Woodford, pg. 38 † Dustin Hellberg, pg. 41 Anja Müller-Wood, Ph.D. † Jennifer Vonk, pg. 43 † Edwin J.C. van Leeuwen and Lysanne Snijders, pg. 46 SCIENCE CONSULTANT † Leif Cocks, pg. 48 Kathleen A. Nolan, Ph.D. † RESPONSE to Comments by Shawn Thompson, pg. 48 EDITORIAL INTERN Angelica Schell † Contributor Biographies, pg. 54 Although this is an open-access journal where papers and articles are freely disseminated across the internet for personal or academic use, the rights of individual authors as well as those of the journal and its editors are none- theless asserted: no part of the journal can be used for commercial purposes whatsoever without the express written consent of the editor. Cite as: ASEBL Journal ASEBL Journal Copyright©2019 E-ISSN: 1944-401X [email protected] www.asebl.blogspot.com Member, Council of Editors of Learned Journals ASEBL Journal – Volume 14 Issue 1, January 2019 From the Editors Shawn Thompson is the first to admit that he is not a scientist, and his essay does not pretend to be a scientific paper. -

Finding Koko

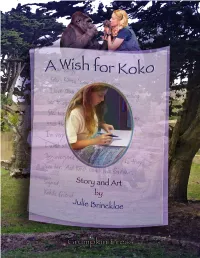

1 A Wish for Koko by Julie Brinckloe 2 This book was created as a gift to the Gorilla Foundation. 100% of the proceeds will go directly to the Foundation to help all the Kokos of the World. Copyright © by Julie Brinckloe 2019 Grumpkin Press All rights reserved. Photographs and likenesses of Koko, Penny and Michael © by Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation Koko’s Kitten © by Penny Patterson, Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation No part of this book may be used or reproduced in whole or in part without prior written consent of Julie Brinckloe and the Gorilla Foundation. Library of Congress U.S. Copyright Office Registration Number TXu 2-131-759 ISBN 978-0-578-51838-1 Printed in the U.S.A. 0 Thank You This story needed inspired players to give it authenticity. I found them at La Honda Elementary School, a stone’s throw from where Koko lived her extraordinary life. And I found it in the spirited souls of Stella Machado and her family. Principal Liz Morgan and teacher Brett Miller embraced Koko with open hearts, and the generous consent of parents paved the way for students to participate in the story. Ms. Miller’s classroom was the creative, warm place I had envisioned. And her fourth and fifth grade students were the kids I’d crossed my fingers for. They lit up the story with exuberance, inspired by true affection for Koko and her friends. I thank them all. And following the story they shall all be named. I thank the San Francisco Zoo for permission to use my photographs taken at the Gorilla Preserve in this book. -

Tropical Malady: Film & the Question of the Uncanny Human-Animal

etropic 10(2011): Creed, Tropical Malady | 131 Tropical Malady: Film & the Question of the Uncanny Human-Animal “The tiger trails you like a shadow/ his spirit is starving and lonesome/I see you are his prey and his companion” – Tropical Malady. Barbara Creed University of Melbourne Abstract The acclaimed Thai film, Tropical Malady (2004), represents the tropics as a surreal place where conscious and unconscious are as inextricably entwined. Directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Tropical Malady presents two interconnected stories: one a quirky gay love story; the other a strange disconnected narrative about a shape-shifting shaman, a man-beast and a ghostly tiger. This paper will argue that from it beginnings in the silent period, the cinema has created an uncanny zone of tropicality where human and animal merge. rom its beginnings in the early twentieth century the cinema has expressed an F enduring fascination with the tropics as an imaginary space. While many filmmakers have envisaged the tropics as an unspoiled paradise (Bird of Paradise, 1932, 1951; The Moon of Manakoora, 1943; South Pacific, 1958), a view which has its origins in classical times, others have represented the tropics as a deeply uncanny zone where familiar and unfamiliar coalesce. It is as if the heat and intensity of the tropics has liquefied matter until normally incommensurate forms are able to dissolve almost imperceptibly into each other. In this process the boundaries between different systems of thought, ideas and ethics similarly dissipate, creating a space for new and often subversive ideas to flourish. As Driver and Martins state, the meaning of “tropicality” is so elastic a number of discourses have been able to shape it to suit their own purposes. -

BRIGANCE Readiness Activities for Emerging K Children

BRIGANCE® Readiness Activities for Emerging K Children • Reading • Mathematics • Additional Support for Emerging K ©Curriculum Associates, LLC Click on a title to go directly to that page. Contents Mathematics BRIGANCE Activity Finder Number Concepts ............................ 89 Connecting to i-Ready Next Steps: Reading ...........iii Counting ................................... 98 Connecting to i-Ready Next Steps: Mathematics ........iv Reads Numerals ............................. 104 Additional Support for Emerging K .................. v Numeral Comprehension .......................110 Numerals in Sequence .........................118 Quantitative Concepts ........................ 132 BRIGANCE Readiness Activities Shape Concepts ............................ 147 Reading Joins Sets ................................. 152 Body Parts ................................... 1 Directional/Positional Concepts .................. 155 Colors ..................................... 12 Response to and Experience with Books ............ 21 Additional Support for Emerging K Prehandwriting .............................. 33 General Social and Emotional Development ......... 169 Visual Discrimination .......................... 38 Play Skills and Behaviors ...................... 172 Print Awareness and Concepts ................... 58 Initiative and Engagement Skills and Behaviors ....... 175 Reads Uppercase and Lowercase Letters ............ 60 Self-Regulation Skills and Behaviors ...............177 Prints Uppercase and Lowercase Letters in Sequence .. 66 -

An Enlightened Future for Bristol Zoo Gardens

OURWORLD BRISTOL An Enlightened Future for Bristol Zoo Gardens An Enlightened Future for CHAPTERBristol EADING / SECTIONZoo Gardens OUR WORLD BRISTOL A magical garden of wonders - an oasis of learning, of global significance and international reach forged from Bristol’s long established place in the world as the ‘Hollywood’ of natural history film-making. Making the most of the city’s buoyant capacity for innovation in digital technology, its restless appetite for radical social change and its celebrated international leadership in creativity and story-telling. Regenerating the site of the first provincial zoological garden in the World, following the 185 year old Zoo’s closure, you can travel in time and space to interact in undreamt of ways with the wildest and most secret aspects of the animal kingdom and understand for the first time where humankind really sits within the complex web of Life on Earth. b c OURWORLD BRISTOL We are pleased to present this preliminary prospectus of an alternative future for Bristol's historic Zoo Gardens. We do so in the confidence that we can work with the Zoo, the City of Bristol and the wider community to ensure that the OurWorld project is genuinely inclusive and reflects Bristol’s diverse population and vitality. CONTENTS Foreword 2 A Site Transformed 23 A Transformational Future for the Our Challenge 4 Zoo Gardens 24 Evolution of the Site Through Time 26 Site Today 27 Our Vision 5 Reimagining the Site 32 A Zoo Like No Other 6 Key Design Moves 34 Humanimal 7 Anatomy 38 Time Bridge 10 Alfred the Gorilla Lives Again 12 Supporters And Networks 45 Supporters 46 Networks 56 Advisors and Contact 59 Printed in Bristol by Hobs on FSC paper 1 FOREWORD OURWORLD BRISTOL FOREWORD Photo: © Dave Stevens Our demand for resources has Bristol Zoo will hold fond This century we are already pushed many other memories for so many.