Appendix of Unresolved Complaints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food and Drug Administration, HHS § 146.185

Food and Drug Administration, HHS § 146.185 of the food, without intervening writ- weight of the preservative used. If the ten, printed, or graphic matter. food is packed in container sizes that are less than 19 liters (5 gallons), the [42 FR 14414, Mar. 15, 1977, as amended at 44 FR 36378, June 22, 1979; 58 FR 2881, Jan. 6, label shall bear a statement indicating 1993] that the food is for further manufac- turing use only. § 146.153 Concentrated orange juice (e) Wherever the name of the food ap- for manufacturing. pears on the label so conspicuously as (a) Concentrated orange juice for to be easily seen under customary con- manufacturing is the food that com- ditions of purchase, the statement plies with the requirements of com- specified in paragraph (d) of this sec- position and label declaration of ingre- tion for naming the preservative ingre- dients prescribed for frozen con- dient used shall immediately and con- centrated orange juice by § 146.146, ex- spicuously precede or follow the name cept that it is either not frozen or is of the food, without intervening writ- less concentrated, or both, and the or- ten, printed, or graphic matter. anges from which the juice is obtained [42 FR 14414, Mar. 15, 1977, as amended at 44 may deviate from the standards for FR 36378, June 22, 1979; 58 FR 2882, Jan. 6, maturity in that they are below the 1993] minimum Brix and Brix-acid ratio for such oranges: Provided, however, that § 146.185 Pineapple juice. the concentration of orange juice solu- (a) Identity. -

THICK & EASY Clear Thickened Prune Drink

Item Number: 72461 Product THICK & EASY Clear Name: Thickened Prune Drink - Nectar - Lvl 2 - 24/4oz Master Item Name: BEV-THKRTS 24/4 PRNE-NCT L2 Product Fact Sheet Product Information UDEX Information UCC Manufacturer ID: 99429 UDEX Department: 17 - NON-ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES Manufacturer Sequence: 284 UDEX Category: 144 - NON-ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES OTHER - READY TO DRINK UDEX Sub Category: 484 - JUICE/NECTAR DRINKS - READY TO DRINK Brand: GPC Code: 10000222 - Juice Drinks - Ready to Drink (Perishable) Specifications Ship Container UPC: 10099429724618 Storage Range Unit UPC: Recommended: 70 F Specification Number: 10207 Maximum: 90 F Pallet Code: 12 Minimum: 40 F Pallet Pattern: 10 x 17 = 170 Description: Do Not Freeze Full Pallet: 1288.60 lbs. Catch Weight? NO Kosher? Yes Leaker Allowance: N Contains Allergens: No Allergens present Truckload Quantity: 33 Bioengineering Information: Has not been evaluated for BE content. Total Code Days: 365 Min Delivered Shelf Life Days: Master Dimensions Case Dimensions: 15.94''L x 10.63''W x 2.69''H Cubic Feet: .260 CUFT Unit Quantity: 24 Net Weight: 6.82 LB Unit Size: Gross Weight: 7.58 LB Pack: CASE Tare Weight: .76 LB Nutrition Facts Domestic Nutrition Only Method: Product Form: NLEA Adjusted Values: Y Label Number: Child Nutrition Label: Food Category Code: Recipe Code: Source Code: Product Description General Description: THICK & EASY Clear Thickened Prune Drink - Nectar - Lvl 2 - 24/4oz Benefits of Using This Product: Pre-thickened prune juice is a great tasting alternative to other juices with laxative benefits as well. Product Claims: KOSHER - CIRCLE U - ORTHODOX UNION Nutrition Claims: Excellent Source of Fiber List of Ingredients: Nectar Consistency, 10 % Juice from Concentrate with Added Ingredients Ingredients: Water, Sugar, Prune Base (Concentrated Prune Juice, Caramel Color, Water, Natural Flavor, Citric Acid, Gum Arabic, Sunflower Oil, Ascorbic Acid [Vitamin C], Glycerol Ester of Wood Rosin, Potassium Sorbate [Preservative], Brominated Vegetable Oil), Resistant Maltodextrin, Xanthan Gum, Ascorbic Acid, Citric Acid. -

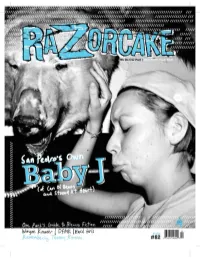

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Cold Chisel to Roll out the Biggest Archival Release in Australian Music History!

Cold Chisel to Roll Out the Biggest Archival Release in Australian Music History! 56 New and Rare Recordings and 3 Hours of Previously Unreleased Live Video Footage to be Unveiled! Sydney, Australia - Under total media embargo until 4.00pm EST, Monday, 27 June, 2011 --------------------------------------------------------------- 22 July, 2011 will be a memorable day for Cold Chisel fans. After two years of exhaustively excavating the band's archives, 22 July will see both the first- ever digital release of Cold Chisel’s classic catalogue as well as brand new deluxe reissues of all of their CDs. All of the band's music has been remastered so the sound quality is better than ever and state of the art CD packaging has restored the original LP visuals. In addition, the releases will also include previously unseen photos and liner notes. Most importantly, these releases will unleash a motherlode of previously unreleased sound and vision by this classic Australian band. Cold Chisel is without peer in the history of Australian music. It’s therefore only fitting that this reissue program is equally peerless. While many major international artists have revamped their classic works for the 21st century, no Australian artist has ever prepared such a significant roll out of their catalogue as this, with its specialised focus on the digital platform and the traditional CD platform. The digital release includes 56 Cold Chisel recordings that have either never been released or have not been available for more than 15 years. These include: A “Live At -

Prune Juice Concentrate

Additives in tobacco products Prune Juice Concentrate Additives are substances intentionally added to tobacco been classified by the International Agency for Research on products by tobacco industry in order to render toxic tobacco Cancer (a leading expert cancer organisation). Other toxic products palatable and acceptable to consumers. compounds that irritate the airways are also formed (e.g. acrolein or 2-furfural). Prunes are ripe plums that are dried. Concentrated prune juice is extracted from softened prunes. As a fruit extract, The sugars also produce acidic compounds, which make prune juice concentrate is very rich in sugars and is therefore it harder for the nicotine in the cigarette smoke to reach naturally sweet. the brain. This forces smokers to inhale deeper and to also consume more cigarettes to get their nicotine fix. Further- General uses more, the use of prune juice concentrate may be indirectly harmful due to the formation of compounds called aldehydes Prune juice concentrate has many uses in the food industry, (e.g. acetaldehyde), which can make cigarettes more addictive e.g. as a sweetener, colour and flavour enhancer, a binding by enhancing the addictive potential of nicotine. Aldehydes agent in cereal bars, and also as a ‘humectant’ to help keep are very reactive and produce compounds such as the subs- cakes and cookies moist. tance harman, which can also enhance addictiveness due to its mood-enhancing effect on the brain. Reported tobacco industry uses Prune juice concentrate is used to smoothen and mildly Prune juice concentrate (along with other extracts from either sweeten the smoke. It imparts a sweet taste making the the plum or prune) is reportedly used by tobacco manufac- smoke more palatable. -

How Diet and Daily Habits May Affect Your Bladder

London Women’s Care 803 Meyers Baker Rd. London, KY 40741 606-878-3240 How Diet and Daily Habits May Affect Your Bladder There is no “diet” to cure incontinence. However, there are certain dietary matters you should know about. Many people who have bladder control problems reduce the amount of liquids they drink in the hope that they will need to urinate less often. While less liquid through the mouth does result in less liquid in the form of urine, the smaller amount of urine may be more highly concentrated and, thus, irritating to the bladder surface. Highly concentrated, dark yellow, strong urine may cause you to go the bathroom more frequently. It also encourages growth of bacteria. And when bacteria begin to grow, infection sets in, and incontinence may be the result. Do not restrict fluids to control incontinence without the advice of your physician. Always follow your doctor’s orders. And, when in doubt, consult a physician, nurse, or pharmacist. Some foods cause urine to smell bad or peculiar. The most notable of these foods is asparagus. Some other foods may affect the way your urine smells. Another cause of foul-smelling urine, and the most dangerous cause, is urinary tract infection. If you notice that your urine has a strong odor to it and you have not eaten any foods that would cause this, you should see a physician and have a specimen of your urine tested for infection. Some medicines may cause your urine to be discolored or have an unusual odor. Some are medicines that you take for bladder inflammation or for urine tests. -

Northbound Single-Lane by Marsha Mathews Finishing Line Press AA Poeticpoetic Traveloguetravelogue Ofof Thethe Heartheart

Issue Number Fifteen Spring/Summer 2012 In Case of Rapture Lefty Frizzell Fiction by William Dockery A story of a one-of-a-kindness The Way ’Twas A memory captured by a snapshot A Flying Elizabeth Family Reunion and Hazel Families that fly together... The women behind the picture Brush With the Law Northbound Non-ignorance of the law is an excuse Single - Lane A collection of Southern poetry Daddy’s in the Closet ...and that’s where he’s going to stay Lisa Love’s Life Where humor and reality hang out Kids and Politics Why Daddy drinks California Itch Go west, young man with apologies to Norman Rockwell E-Publisher’s Corner CaliforniaCalifornia ItchItch found the above picture tucked inside an old college “Because you can’t go any further west,” someone else said. yearbook. It featured the original members of Contents “Can’t go no further—this here’s Under Pressure, a band that we hastily assembled in injun territory.” Copas said, quoting September of 1970 for a freshman talent show at the the California stream-of-conscious- ness comedy troupe, Firesign Theater. East Tennessee Baptist college we attended. All of us were fed up with our par- IIThe only member of Contents not was before holes in jeans were cool). ticular circumstances. Kling and Copas pictured was (Dancin’) Dan (the Man) BoatRamp, the farmdog, was trying were bored with Nashville, and those Schlafer; he had joined us in early 1971, to imitate my stance and smile for the of us finishing up our college careers and by the time this was snapped—in camera. -

Advanced Diet As Tolerated/Diet of Choice This Is for Communication Only

SVMC INTERPRETATION OF DIET ORDERS SVMC menu plans are developed using best evidenced based practice guidelines. The Clinical Diet Manual is the basis for our menu planning and patient education materials. Listed below is a brief summary of the menu plans provided by SVMC and any specifics that may differ from the Clinical Diet Manual. Our regular non select menu serves as the basis for all our menu plans and follows the Dietary Reference Intake (DRI’s/RDA’s) for our population of male 51-70 years old. Menus are designed to meet nutritional requirements specified by the 2011 update of the DRI’s from the Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, National Academies of Science’s guidelines. This menu is then further modified to meet the specific needs of each patient based on diet order, nutritional status, food allergies, age, cultural preferences and food likes and dislikes. Current Dietary Reference Intakes recommend that Sodium intake remain less than 2300 mg per day. In order to meet their preferences and maintain intake, most diets that do not indicate a Sodium restriction will exceed this value. A sodium restriction should be ordered if needed. Due to limitations within our nutrient database (CBORD) we do not have values available to us for all nutrients. Currently our database is incomplete for: biotin, choline, chromium, molybdenum, fluoride, iodine, chloride, linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid and sometimes other micronutrients. Thin liquids are a default for all diets. Nectar, honey, pudding fluid consistency or fluid restriction needs to be ordered under “DIET CATEGORY”. If oral nutrition supplements (ONS) are ordered BID with meals, i.e. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Analysis of Fruit Juices and Drinks of Ascorbic Acid Content

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1969 Analysis of Fruit Juices and Drinks of Ascorbic Acid Content Anna Man-saw Liu Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Food Science Commons Recommended Citation Liu, Anna Man-saw, "Analysis of Fruit Juices and Drinks of Ascorbic Acid Content" (1969). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 4851. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/4851 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANALYSTS OF FRUIT JUICES AND DRINKS OF ASCORBIC ACID CONTENT by Anna Man-saw Liu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Food and Nutrition UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY• Logan,1969 Utah ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Sincere appreciation is expressed to Dr. Ethelwyn B. Wilcox, Head of the Food and Nutrition Department, for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Many thanks to Mrs. Ruth E. Wheeler, Assistant Professor of Food and Nutrition, for her able guidance on this research. Appreciation is also expressed to Dr. Harris 0 . Van Orden , Professor of Chemistry, for his many helpful suggestions and for serv ing as a committee member . Also sincere gratefulness to Dr . Deloy G. Hendricks, Assistant Professor of Food and Nutrition, for his many helps during the experimental procedures. The author wishes to express her gratitude to her husband , Mr . -

John Rose Fasting Protocol 4/21/17, 2�18 PM

John Rose Fasting Protocol 4/21/17, 218 PM John Rose Fasting Protocol Fasting Ingredients Recommended Fruit Juices for bulk of calories: Watermelon (with or without rind), Orange Honey Dew Melon, Oranges, Cantaloupes, Grapes, Apples, Carrots Quick Calorie Reference: Watermelon Juice Gallon (128oz, or 3.78L) = ~1200 calories Orange Juice Gallon (128oz, or 3.78L) = ~1785 calories Grape Juice Gallon (128oz, or 3.78L) = ~2428 calories Apple Juice Gallon (128oz, or 3.78L) = ~1872 calories Carrot Juice Gallon (128oz, or 3.78L) = ~1510 calories Recommended Green Juice Ingredients: Cucumber, Celery, Parsley, Kale, Jalapeno, Lemon, Carrot, Ginger, Turmeric, Apples, Garlic Quick Green Juice Recipe: 2 large cucumbers (or replace 1 cucumber with 1 large stalk of celery) 1 large bundle of Green kale (any kale may be used) 1 bundle of Italian Parsley ¼ yellow lemon (peeled) 3 medium-large sized apples Ginger to taste Turmeric to taste (optional) Garlic to taste (if adventurous, but optional) This recipe approx 200 calories. Supplements: Essential Fatty Acids Men: Flax Oil daily, 1-2 tablespoons daily Women: Hemp Oil daily, 1-2 tablespoons daily Recommended Juicer: Tribest Green Star Elite - twin auger juicer, exceptional juice quality and yield, very robust *Tribest Slowstar not recommend - great juicer but overheats in around 30 minutes. Not ideal for juice fasting. How-To-Fast, John Rose Protocol 1) Recommended Drinking Amounts per Day: Rule of thumb is 1 gallon, regardless of what type of juice you choose. Some juices have less calories than others such as watermelon so you will probably be inclined to drink more of it. If energy levels are https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Zt2ZiYHuRGMIPpoP6g-kZ1cnsFG_DqdxcbI-UpbSLLw/pub Page 1 of 3 John Rose Fasting Protocol 4/21/17, 218 PM low you probably need a little more juice. -

Cold Chisel Breakfast at Sweethearts Mp3, Flac, Wma

Cold Chisel Breakfast At Sweethearts mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Breakfast At Sweethearts Country: Australia Style: Pop Rock, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1134 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1254 mb WMA version RAR size: 1886 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 848 Other Formats: MMF VOX MPC MIDI VQF MP2 VOX Tracklist A1 Conversations 4:28 A2 Merry Go Round 3:40 A3 Dresden 3:52 A4 Goodbye (Astrid Goodbye) 2:49 A5 Plaza 2:06 B1 Shipping Steel 3:22 B2 I'm Gonna Roll Ya 3:23 B3 Showtime 3:42 B4 Breakfast At Sweethearts 4:06 B5 The Door 4:15 Companies, etc. Manufactured By – WEA Records Pty. Limited Distributed By – WEA Records Pty. Limited Phonographic Copyright (p) – WEA Records Pty. Limited Copyright (c) – WEA Records Pty. Limited Published By – Rondor Music Pty. Ltd. Produced At – Albert Studios Engineered At – Albert Studios Mastered At – EMI Studios 301 Credits Art Direction – Ken Smith Bass – Phil Small Drums – Steve Prestwich Guitar – Ian Moss Harmonica – Dave Blight Management [Personal Management] – Rod Willis Management [Tour Management] – Dave Ferguson Photography By [At The Marble Bar, Sydney Hilton Hotel] – Greg Noakes Piano, Organ, Backing Vocals – Don Walker Producer, Mastered By – Richard Batchens Slide Guitar – Tony Faehse (tracks: B1) Vocals – Ian Moss (tracks: A5), Jim Barnes* Written-By – Walker*, Moss* (tracks: A3), Barnes* (tracks: A4) Notes Produced and engineered at Albert Studios, Sydney Mastered at E.M.I. Studios, Sydney On sleeve: "This is the neon strip Where baracudas cruise Drivers, midnight looters Zipped in sharkskin jackets Waiting for a Mark Their brains are soft computers" Distributed by WEA Records Pty.