Leader's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi's View on Judaism and Zionism in Light of an Interreligious

religions Article Gandhi’s View on Judaism and Zionism in Light of an Interreligious Theology Ephraim Meir 1,2 1 Department of Jewish Philosophy, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel; [email protected] 2 Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (STIAS), Wallenberg Research Centre at Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa Abstract: This article describes Gandhi’s view on Judaism and Zionism and places it in the framework of an interreligious theology. In such a theology, the notion of “trans-difference” appreciates the differences between cultures and religions with the aim of building bridges between them. It is argued that Gandhi’s understanding of Judaism was limited, mainly because he looked at Judaism through Christian lenses. He reduced Judaism to a religion without considering its peoplehood dimension. This reduction, together with his political endeavors in favor of the Hindu–Muslim unity and with his advice of satyagraha to the Jews in the 1930s determined his view on Zionism. Notwithstanding Gandhi’s problematic views on Judaism and Zionism, his satyagraha opens a wide-open window to possibilities and challenges in the Near East. In the spirit of an interreligious theology, bridges are built between Gandhi’s satyagraha and Jewish transformational dialogical thinking. Keywords: Gandhi; interreligious theology; Judaism; Zionism; satyagraha satyagraha This article situates Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s in the perspective of a Jewish dialogical philosophy and theology. I focus upon the question to what extent Citation: Meir, Ephraim. 2021. Gandhi’s religious outlook and satyagraha, initiated during his period in South Africa, con- Gandhi’s View on Judaism and tribute to intercultural and interreligious understanding and communication. -

Republication, Copying Or Redistribution by Any Means Is

Republication, copying or redistribution by any means is expressly prohibited without the prior written permission of The Economist The Economist April 5th 2008 A special report on Israel 1 The next generation Also in this section Fenced in Short-term safety is not providing long-term security, and sometimes works against it. Page 4 To ght, perchance to die Policing the Palestinians has eroded the soul of Israel’s people’s army. Page 6 Miracles and mirages A strong economy built on weak fundamentals. Page 7 A house of many mansions Israeli Jews are becoming more disparate but also somewhat more tolerant of each other. Page 9 Israel at 60 is as prosperous and secure as it has ever been, but its Hanging on future looks increasingly uncertain, says Gideon Licheld. Can it The settlers are regrouping from their defeat resolve its problems in time? in Gaza. Page 11 HREE years ago, in a slim volume enti- abroad, for Israel to become a fully demo- Ttled Epistle to an Israeli Jewish-Zionist cratic, non-Zionist state and grant some How the other fth lives Leader, Yehezkel Dror, a veteran Israeli form of autonomy to Arab-Israelis. The Arab-Israelis are increasingly treated as the political scientist, set out two contrasting best and brightest have emigrated, leaving enemy within. Page 12 visions of how his country might look in a waning economy. Government coali- the year 2040. tions are fractious and short-lived. The dif- In the rst, it has some 50% more peo- ferent population groups are ghettoised; A systemic problem ple, is home to two-thirds of the world’s wealth gaps yawn. -

Electoral Processes in the Mediterranean

Electoral Processes Electoral processes in the Mediterranean This chapter provides information on jority party if it does not manage to Gorazd Drevensek the results of the presidential and leg- obtain an absolute majority in the (New Slovenia Christian Appendices islative elections held between July Chamber. People’s Party, Christian Democrat) 0.9 - 2002 and June 2003. Jure Jurèek Cekuta 0.5 - Parties % Seats Participation: 71.3 % (1st round); 65.2 % (2nd round). Monaco Nationalist Party (PN, conservative) 51.8 35 Legislative elections 2003 Malta Labour Party (MLP, social democrat) 47.5 30 9th February 2003 Bosnia and Herzegovina Med. Previous elections: 1st and 8th Februa- Democratic Alternative (AD, ecologist) 0.7 - ry 1998 Federal parliamentary republic that Parliamentary monarchy with unicam- Participation: 96.2 %. became independent from Yugoslavia eral legislative: the National Council. in 1991, and is formed by two enti- The twenty-four seats of the chamber ties: the Bosnia and Herzegovina Fed- Slovenia are elected for a five-year term; sixteen eration, known as the Croat-Muslim Presidential elections by simple majority and eight through Federation, and the Srpska Republic. 302-303 proportional representation. The voters go to the polls to elect the 10th November 2002 Presidency and the forty-two mem- Previous elections: 24th November bers of the Chamber of Representa- Parties % Seats 1997 tives. Simultaneously, the two entities Union for Monaco (UPM) 58.5 21 Parliamentary republic that became elect their own legislative bodies and National Union for the Future of Monaco (UNAM) independent from Yugoslavia in 1991. the Srpska Republic elects its Presi- Union for the Monegasque Two rounds of elections are held to dent and Vice-President. -

Israel: Background and Relations with the United States

Israel: Background and Relations with the United States Carol Migdalovitz Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs January 7, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33476 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Israel: Background and Relations with the United States Summary On May 14, 1948, the State of Israel declared its independence and was immediately engaged in a war with all of its neighbors. Armed conflict has marked every decade of Israel’s existence. Despite its unstable regional environment, Israel has developed a vibrant parliamentary democracy, albeit with relatively fragile governments. Early national elections were held on February 10, 2009. Although the Kadima Party placed first, parties holding 65 seats in the 120- seat Knesset supported opposition Likud party leader Benjamin “Bibi” Netanyahu, who was designated to form a government. Netanyahu put together a coalition comprising his own Likud, Yisrael Beiteinu (Israel Our Home), Shas, Labor, Habayet Hayehudi (Jewish Home), and the United Torah Judaism (UTJ) parties which controls 74 Knesset seats. Israel has an advanced industrial, market economy with a large government role. Israel’s foreign policy is focused largely on its region, Europe, and the United States. Israel’s foreign policy agenda begins with Iran, which it views as an existential threat due to Tehran’s nuclear ambitions and support for anti-Israel terrorists. Achieving peace with its neighbors is next. Israel concluded peace treaties with Egypt in 1979 and Jordan in 1994, but not with Syria and Lebanon. Israel unilaterally withdrew from southern Lebanon in 2000. Hezbollah, which then took over the south, sparked a 34-day war when it kidnapped two Israeli soldiers on July 12, 2006. -

The Haredim As a Challenge for the Jewish State. the Culture War Over Israel's Identity

SWP Research Paper Peter Lintl The Haredim as a Challenge for the Jewish State The Culture War over Israel’s Identity Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs SWP Research Paper 14 December 2020, Berlin Abstract ∎ A culture war is being waged in Israel: over the identity of the state, its guiding principles, the relationship between religion and the state, and generally over the question of what it means to be Jewish in the “Jewish State”. ∎ The Ultra-Orthodox community or Haredim are pitted against the rest of the Israeli population. The former has tripled in size from four to 12 per- cent of the total since 1980, and is projected to grow to over 20 percent by 2040. That projection has considerable consequences for the debate. ∎ The worldview of the Haredim is often diametrically opposed to that of the majority of the population. They accept only the Torah and religious laws (halakha) as the basis of Jewish life and Jewish identity, are critical of democratic principles, rely on hierarchical social structures with rabbis at the apex, and are largely a-Zionist. ∎ The Haredim nevertheless depend on the state and its institutions for safeguarding their lifeworld. Their (growing) “community of learners” of Torah students, who are exempt from military service and refrain from paid work, has to be funded; and their education system (a central pillar of ultra-Orthodoxy) has to be protected from external interventions. These can only be achieved by participation in the democratic process. ∎ Haredi parties are therefore caught between withdrawal and influence. -

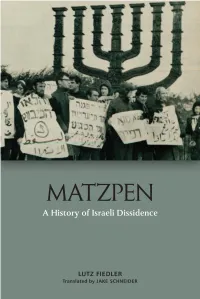

9781474451185 Matzpen Intro

MATZPEN A History of Israeli Dissidence Lutz Fiedler Translated by Jake Schneider 66642_Fiedler.indd642_Fiedler.indd i 331/03/211/03/21 44:35:35 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com Original version © Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, 2017 English translation © Jake Schneider, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd Th e Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/15 Adobe Garamond by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5116 1 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5118 5 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5119 2 (epub) Th e right of Lutz Fiedler to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Originally published in German as Matzpen. Eine andere israelische Geschichte (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017) Th e translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International – Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Th yssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Offi ce, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association). -

Guide to Traditional Jewish Observance in a Hospital Ohkujv ,Hcc Ohtmnbv Ohkujk Lhrsn

Guide to Traditional Jewish Observance in a Hospital ohkujv ,hcc ohtmnbv ohkujk lhrsn By Rabbi Jason Weiner Cover art: Part of the “Jewish Contributions to Medicine” mural by Terry Schoonhover. Commissioned for Cedars-Sinai and on permanent display in the Harvey Morse Auditorium. Courtesy of Cedars-Sinai. Guide to Traditional Jewish Observance in a Hospital ohkujv ,hcc ohtmnbv ohkujk lhrsn By Rabbi Jason Weiner © 2012 - Jason Weiner – All rights reserved. ,nab hukhgku rfzk Dedicated in Loving Memory of v’’g cegh icutr rwwc ohhj kthrt wr Ariel Avrech A”H /v/c /m/b/, By his Beloved Grandparents Rabbi Philip Harris Singer k"mz and Mrs. Celia Singer Dedicated by awwung van rwwc ktezjh wr ~ Howard Hyzen In Honor of his Beloved Wife Claire Hyzen whjha u,tuprku u,ufzk uhvh ukt vru, hrcsu uck ,csb Table of Contents Letters of Approbation .................................................... 9 Introduction ............................................................ 14 I. Categories of Illness .................................................... 17 A. Minor Ailments .....................................................17 B. Incapacitating and Life-Threatening Illnesses ............................17 II. Shabbat .............................................................. 21 A. Dangerously Ill Patient on Shabbat/Holidays – General Principles ..........21 B. “Shinui” Doing a Shabbat labor in an awkward, backhanded manner ........24 C. “Amira L’Akum” Asking someone who is not Jewish to violate Shabbat .......25 D. Use of Electricity ....................................................25 -

Guide to Traditional Jewish Observance in a Hospital Ohkujv ,Hcc Ohtmnbv Ohkujk Lhrsn

Guide to Traditional Jewish Observance in a Hospital ohkujv ,hcc ohtmnbv ohkujk lhrsn Rabbi Jason Weiner Cover art: Part of the “Jewish Contributions to Medicine” mural by Terry Schoonhover. Commissioned for Cedars-Sinai and on permanent display in the Harvey Morse Auditorium. Courtesy of Cedars-Sinai. Guide to Traditional Jewish Observance in a Hospital ohkujv ,hcc ohtmnbv ohkujk lhrsn By Rabbi Jason Weiner © 2017 - Jason Weiner – All rights reserved. 3rd Edition ,nab hukhgku rfzk Dedicated in Loving Memory of v’’g cegh icutr rwwc ohhj kthrt wr Ariel Avrech A”H /v/c /m/b/, By his Beloved Grandparents Rabbi Philip Harris Singer k"mz and Mrs. Celia Singer Dedicated by awwung van rwwc ktezjh wr ~ Howard Hyzen In Honor of his Beloved Wife Claire Hyzen whjha u,tuprku u,ufzk uhvh ukt vru, hrcsu uck ,csb Table of Contents Letters of Approbation . 6 Introduction . 12 I . Categories of Illness . 15 A. Minor Ailments .....................................................15 B. Incapacitating and Life-Threatening Illnesses ............................15 II . Shabbat . 19 A. Dangerously Ill Patient on Shabbat/Holidays – General Principles. .19 B. “Shinui” Doing a Shabbat labor in an awkward, backhanded manner ........22 C. Asking someone who is not Jewish to violate Shabbat “Amira L’Akum”. 23 D. Use of Electricity ....................................................24 E. Elevators, Electric Doors and Automatic Sensors on Shabbat ...............29 F. The Use of a Telephone ...............................................33 G. Use of the Call Button & Adjustable Bed ................................35 H. Parking and Turning Off a Car ........................................36 I. Discharge on Shabbat/Holidays ........................................37 J. Writing on Shabbat ...................................................39 K. Shabbat Candles .....................................................41 L. Kiddush & Havdalah . 42 M. -

Crossroads: the Future of the U.S.-Israel Strategic Partnership Haim Malka Foreword by Samuel W

Malka Crossroads: The Future of the U.S.-Israel Strategic Partnership Haim Malka Foreword by Samuel W. Lewis The U.S.-Israel partnership is under unprecedented strain. The relationship is deep and coopera- tion remains robust, but the challenges to it now are more profound than ever. Growing differ- ences could undermine the national security of both the United States and Israel, making strong cooperation uncertain in an increasingly volatile and unpredictable Middle East. This volume explores the partnership between the United States and Israel and analyzes how political and strategic dynamics are reshaping the relationship. Drawing on original research and dozens of interviews with U.S. and Israeli officials and former officials, the study traces the development CROSSROADS of the U.S.-Israel relationship, analyzes the sources of current tension, and suggests ways for- ward for policymakers in both countries. The author weaves together historical accounts with current analysis and debates to provide insight into this important yet changing relationship. It is a sobering and keen analysis for anyone concerned with the future of the U.S.-Israel partner- ship and the broader Middle East. Haim Malka is deputy director and senior fellow of the Middle East Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Crossroads The Future of the U.S.-Israel Strategic Partnership HAIM MALKA ISBN 978-0-89206-660-5 FOREWORD BY SAMUEL W. LEWIS Center for Strategic and International Studies Washington, D.C. Ë|xHSKITCy066605zv*:+:!:+:! CSIS 2011 C ROSSROADS ABOUT CSIS At a time of new global opportunities and challenges, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) provides strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to decisionmakers in government, in- ternational institutions, the private sector, and civil society. -

Introduction

Introduction For nearly two millennia, the Jews were a stateless people. No wonder then that issues like religion and state, the temporal and the sacerdotal, war and peace, faith and the rule of secular law, Halacha and the proper form of government were usually glossed over or relegated to scholarly, theoretical discourse. While the Christian Middle Ages raged with debate and conflict between the church and the secular sovereign powers, there was little in the way of a parallel Jewish discourse. When such discussions did take place, they were largely philosophical in character, often limited to legal discussions of community versus individual rights or treated in the context of the messianic era when Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel would be restored. The founding of a Jewish state in 1948 transformed this muted, relatively moribund discourse into a new, frequently tumultuous necessity. Unprecedented issues were faced for which the tradition had only incom- plete answers. Rabbis confronted governments with halachic demands just as the newly constituted secular state staked out its claim to authority over issues that intruded upon Jewish religious law. Issues related to the Sabbath, marriage and divorce, dietary laws, army service, and conversion pitted the newly established state against entrenched rabbinic authorities. These issues have been exhaustively treated in a burgeoning scholarly literature. No group in Israeli society has been so profoundly embroiled in the religion-state impasse than the religious Zionists. (We use the lowercase “religious” to emphasize that religious Zionism is not one movement—it is composed of many.) In the past forty years the central flashpoint of this struggle has been the “settlement project” that religious Zionists have championed and spearheaded. -

Online Political Campaigns

Online Political Campaigning: A Bird-Eye's View Azi Lev-On School of Communication, Ariel University Center, Ariel, Israel Paper presented at: "Internet, Politics, Policy 2010: An Impact Assessment", Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford 16-17 September 2010 Introduction The semi-annual TIM survey, measuring Internet exposure and usage patterns (June 2008), shows that broadband Internet penetration in Israel is extensive. Internet usage is estimated at 69% among the adult Jewish population, and 56% among the adult Arab-Palestinian population. The primary uses of the Internet are information search (96%), news reading (89%), and activities such as watching 1 videos (73%) and shopping online (56%).P0F P This article examines if the massive penetration is manifest in the Israeli political arena as well, on both the national and municipal levels, by political players as well as the public. While articles that study online campaigning typically analyze particular case studies, here the goal is to provide a comparative and comprehensive look at a number of campaigns. The fifteen months between November 2007 and February 2009 provide a unique window to examine the penetration and consolidation of the Internet as a medium for political marketing in Israel. In this period, no less than four country-wide elections took place: the general elections for the Israeli parliament (Knesset) in February 2009, and three rounds of municipal elections, one for mayors and heads of local councils in November 2008, and two rounds of elections for regional councils, in November 2007 and January 2009. Note that municipal administration7T in Israel is composed of three levels: cities (in general, municipalities with over 20,000 residents), local councils (in general, municipalities with 2,000-20,000 residents), and regional councils, that are in general composed of a number of communities with less than 2,000 residents. -

Siddur for Shabbat

úáùì øåãéñ Siddur for Shabbat úáùì øåãéñ Siddur for Shabbat David Singer, Editor Berkeley Hillel 5763 2003 i ii Contents Preface iv On Usage v Shabbat Evening Service 1 Shabbat Morning Service 43 Havdalah 95 Supplementary Prayers 97 Songs 103 iii Preface This siddur was first created by the Reform minyan at UC Berkeley, California in the spring of 2003. In deciding to compile this siddur, students embarked on an ambitious process: how could they best combine over twenty distinct creative service packets into one inclusive and comprehensive siddur which would suit the needs of the Berkeley Reform Jewish community’s prayer in all circumstances for years to come? Further, the prayer service, while in need of energy and creativity, was also worthy of respect and in due need of a certain amount of structure which service packets could not provide. It is our hope that this siddur meets that need, and accordingly that it can and will be used for Erev and Shacharit Shabbat and Havdalah services as well as song sessions. Further, it is our hope that this siddur will help to meet the same need in other youth and young adult minyanim for years to come. We thank the many people who have helped to make this siddur a reality, especially to those who spent countless hours compiling and editing. To David Singer, Melissa Loeffler, Jill Cozen-Harel, Becky Gimbel, David Abraham and Athalia Markowitz special thanks are due. The original printing of this siddur would not be possible if not for the generous financial support provided by Temple Beth El of Berkeley, CA.