Celebrity Studies Buying Beyoncé

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AP1 Companies Affiliates

AP1 COMPANIES & AFFILIATES 100% RECORDS BIG MUSIC CONNOISSEUR 130701 LTD INTERNATIONAL COLLECTIONS 3 BEAT LABEL BLAIRHILL MEDIA LTD (FIRST NIGHT RECORDS) MANAGEMENT LTD BLIX STREET RECORDS COOKING VINYL LTD A&G PRODUCTIONS LTD (TOON COOL RECORDS) LTD BLUEPRINT RECORDING CR2 RECORDS ABSOLUTE MARKETING CORP CREATION RECORDS INTERNATIONAL LTD BOROUGH MUSIC LTD CREOLE RECORDS ABSOLUTE MARKETING BRAVOUR LTD CUMBANCHA LTD & DISTRIBUTION LTD BREAKBEAT KAOS CURB RECORDS LTD ACE RECORDS LTD BROWNSWOOD D RECORDS LTD (BEAT GOES PUBLIC, BIG RECORDINGS DE ANGELIS RECORDS BEAT, BLUE HORIZON, BUZZIN FLY RECORDS LTD BLUESVILLE, BOPLICITY, CARLTON VIDEO DEAGOSTINI CHISWICK, CONTEMPARY, DEATH IN VEGAS FANTASY, GALAXY, CEEDEE MAIL T/A GLOBESTYLE, JAZZLAND, ANGEL AIR RECS DECLAN COLGAN KENT, MILESTONE, NEW JAZZ, CENTURY MEDIA MUSIC ORIGINAL BLUES, BLUES (PONEGYRIC, DGM) CLASSICS, PABLO, PRESTIGE, CHAMPION RECORDS DEEPER SUBSTANCE (CHEEKY MUSIC, BADBOY, RIVERSIDE, SOUTHBOUND, RECORDS LTD SPECIALTY, STAX) MADHOUSE ) ADA GLOBAL LTD CHANDOS RECORDS DEFECTED RECORDS LTD ADVENTURE RECORDS LTD (2 FOR 1 BEAR ESSENTIALS, (ITH, FLUENTIAL) AIM LTD T/A INDEPENDENTS BRASS, CHACONNE, DELPHIAN RECORDS LTD DAY RECORDINGS COLLECT, FLYBACK, DELTA LEISURE GROPU PLC AIR MUSIC AND MEDIA HISTORIC, SACD) DEMON MUSIC GROUP AIR RECORDINGS LTD CHANNEL FOUR LTD ALBERT PRODUCTIONS TELEVISON (IMP RECORDS) ALL AROUND THE CHAPTER ONE DEUX-ELLES WORLD PRODUCTIONS RECORDS LTD DHARMA RECORDS LTD LTD CHEMIKAL- DISTINCTIVE RECORDS AMG LTD UNDERGROUND LTD (BETTER THE DEVIL) RECORDS DISKY COMMUNICATIONS -

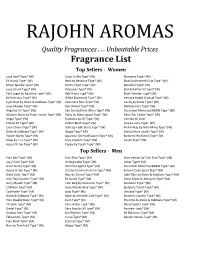

Fragrance List Print

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* -

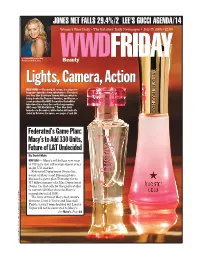

Lights, Camera, Action NEW YORK — the World, It Seems, Is a Stage for Fragrance Launches from Entertainers

JONES NET FALLS 29.4%/2 LEE’S GUCCI AGENDA/14 Women’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • July 29, 2005 • $2.00 ▲ Carmen Electra is Max WWDFRIDAY Factor’s new U.S. face. Beauty Lights, Camera, Action NEW YORK — The world, it seems, is a stage for fragrance launches from entertainers. The latest are True Star Gold from Tommy Hilfiger, which is being fronted by Beyoncé Knowles, and Fusion, a scent produced by AMC Cosmetics that will be introduced in a story line on the long-running ABC soap “All My Children.” True Star Gold launches in December, while Fusion will make its debut in October. For more, see pages 7 and 10. Federated’s Game Plan: Macy’s to Add 330 Units, Future of L&T Undecided By David Moin NEW YORK — Macy’s will balloon next year to 730 units that will occupy almost every major U.S. market. Federated Department Stores Inc., owner of Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s, disclosed a game plan Thursday for its $17 billion merger with May Department Stores Co. that calls for the giant retailer to convert 330 May stores to Macy’s nameplates in fall 2006. The fates of two of May’s best-known divisions, Lord & Taylor and Marshall Y JOHN SCIULLI/WIREIMAGE Field’s, haven’t been decided, but Lord & Taylor will not be converted to Macy’s, See Macy’s, Page18 Y BRYN KENNY; ELECTRA PHOTO B ELECTRA Y BRYN KENNY; PHOTO BY JOHN AQUINO; STYLED B PHOTO BY 2 WWD, FRIDAY, JULY 29, 2005 WWD.COM Jones Profits Drop 29.4% By Vicki M. -

Omarion O Full Album Zip

Omarion, O Full Album Zip Omarion, O Full Album Zip 1 / 3 2 / 3 (The CD audio side includes the entire album, featuring "O," "Touch," and "I'm ... (a signature of the whole disc) in which Omarion shows what it means to emote.. All albums made by Keri Hilson with reviews and song lyrics. ... baby Download November 2019 latest Keri Hilson free audios, album zip mp3 Song. ... Join Napster and access full-length songs on your computer, mobile or home audio system. ..... Spears Gimme Gimme, Ludacris Runaway Love, Omarion Ice Box and 'O', .... Omarion Mixtape by Lloyd, Omarion Hosted by DJ Trigga. ... Stream. Download ... 15.omarion feat. bow wow - im tryna part 2 download .... game red album free download zip, omarion o dirty free mp3 download. ... zip adele 19 album zip free full album zip files. There were two seats facing forward, .... O is the debut studio album by American R&B singer Omarion, released on February 22, 2005 via Epic Records and Sony Urban Music. Despite featuring .... Download O 2005 Album by Omarion in mp3 CBR online alongwith Karaoke. ... O. Explore the page to download mp3 songs or full album zip for free. Feb 22 .... Tracklist: 1. I Wish, 2. Touch, 3. O, 4. I'm Tryna, 5. Drop That Heater, 6. Growing Pains, 7. Take It Off, 8. Never Gonna Let You Go (She's A Keepa), 9. I Know, 10.. Omarion - O - Amazon.com Music. ... Omarion Format: Audio CD. 3.9 out of 5 stars 87 ratings ... Streaming Unlimited MP3 $1.29 · Listen with our. Free App. -

The Symbolic Rape of Representation: a Rhetorical Analysis of Black Musical Expression on Billboard's Hot 100 Charts

THE SYMBOLIC RAPE OF REPRESENTATION: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF BLACK MUSICAL EXPRESSION ON BILLBOARD'S HOT 100 CHARTS Richard Sheldon Koonce A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2006 Committee: John Makay, Advisor William Coggin Graduate Faculty Representative Lynda Dee Dixon Radhika Gajjala ii ABSTRACT John J. Makay, Advisor The purpose of this study is to use rhetorical criticism as a means of examining how Blacks are depicted in the lyrics of popular songs, particularly hip-hop music. This study provides a rhetorical analysis of 40 popular songs on Billboard’s Hot 100 Singles Charts from 1999 to 2006. The songs were selected from the Billboard charts, which were accessible to me as a paid subscriber of Napster. The rhetorical analysis of these songs will be bolstered through the use of Black feminist/critical theories. This study will extend previous research regarding the rhetoric of song. It also will identify some of the shared themes in music produced by Blacks, particularly the genre commonly referred to as hip-hop music. This analysis builds upon the idea that the majority of hip-hop music produced and performed by Black recording artists reinforces racial stereotypes, and thus, hegemony. The study supports the concept of which bell hooks (1981) frequently refers to as white supremacist capitalist patriarchy and what Hill-Collins (2000) refers to as the hegemonic domain. The analysis also provides a framework for analyzing the themes of popular songs across genres. The genres ultimately are viewed through the gaze of race and gender because Black male recording artists perform the majority of hip-hop songs. -

1 Universidade Estadual De Campinas Instituto De Filosofia E

Universidade Estadual de Campinas Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas Mariana Mont’Alverne Barreto Lima As Majors da Música e o Mercado Fonográfico Nacional Dezembro/2009 1 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA ELABORADA PELA BIBLIOTECA DO IFCH - UNICAMP Bibliotecária: Cecília Maria Jorge Nicolau CRB nº 3387 Lima, Mariana Mont’Alverne Barreto L628m As majors da música e o mercado fonográfico nacional / Mariana Mont’Alverne Barreto Lima. - - Campinas, SP : [s. n.], 2009. Orientador: Renato Ortiz. Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. 1. Fonografia. 2. Registros sonoros. 3. Indústria cultural. 4. Empresas multinacionais – Brasil - Séc. XXI. 5. Executivos I. Ortiz, Renato, 1947- II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. III.Título. Título em inglês: The music majors and the national phonographic market Phonography Palavras chaves em inglês (keywords) : Sound recordings Cultural industry Multinational companies – Brazil – 21 st century Executives Área de Concentração: Sociologia cultural Titulação: Doutor em Sociologia Banca examinadora: Renato Ortiz, Maria Celeste Mira, Márcia Tosta Dias, Eduardo Vicente, José Roberto Zan Data da defesa: 02-12-2009 Programa de Pós-Graduação: Sociologia 2 RESUMO Esta pesquisa analisa o funcionamento das quatro gravadoras de discos transnacionais que operam no mercado fonográfico brasileiro, a partir do estabelecimento do disco compacto como suporte padrão para a reprodução e comercialização de música gravada. Partindo da hipótese de que em tempos de globalização da economia e mundialização da cultura, este mercado se comporta e se transforma de modo diverso, investiga-se quais são as características estruturais de tais transformações e como agem os diferentes agentes sociais que disputam este espaço. -

RAISING KANYE Life Lessons from the Mother of a Hip-Hop Superstar

RAISING KANYE Life Lessons from the Mother of a Hip-Hop Superstar Donda West with Karen Hunter POCKET BOOKS NEW YORK LONDON TORONTO SYDNEY Pocket Books A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York. NY 10020 Copyright © 2007 by Donda West All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020 POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Designed by Mary Austin Speaker Skonpelirovano bai esenomera & Perajok (vzoimno) ISBN: 1-4165-5664-8 ISBN: 978-1-4165-5664-0 Visit us on the World Wide Web: http://kenewest.blogspot.com/ Dedicated to the memory of my sister, Klaye Jones, whose laughter was a smile set to music. I'll hear her laughter forever. Acknowledgments I am deeply grateful to my mother and father for making me who I am, and to Kanye West for being my greatest joy. To my entire family for always believing in me. To Miki Woodard, Jeanella Blair, Bill Johnson, Sakiya Sandifer, Alexis Phifer, Michael Newton, Damien Dziepak, Stephan Scog- gins, and to my editor, Lauren McKenna for invaluable feed- back on the manuscript. To Adlaidie Walker and Terry Horton for encouraging me to be bold. To the James Hotel in Chicago for incredible hos- pitality while I worked there on the manuscript. To Ann and Ralph Hines for providing me with the perfect place to re- treat and for being the perfect hosts. -

Gold Star Fragrances Catalog Order Information

Gold Star Fragrances Catalog Date: 2021/10/02 This catalog lists all fragrance oils available online at the time of printing. It does not reflect the prices of related Incense Oil, Massage Oil, Body Lotion and Shampoo available in 16-ounce bottles. The prices shown reflect the 1-, 4-, 8- and 16-ounce fragrance oil sizes. (In some instances the sizes may also be referred to as quarter pound (4 oz), half pound (8 oz) and one pound (16 oz) sizes which is based on shipping weight not liquid content. You can view prices of related options online in QuikScent by clicking on the fragrance oil. The prices and fragrances are subject to change online notice. Order Information You can order online at www.goldstarfragrances.com, or by calling Gold Star Fragrances at: 212-279-4474. You can also order in person at our store located at 8 West 37th Street, NY, NYC 10018. Disclaimer: The catalog does not claim that the list of oils or perfumes are the brand shown. The brand names shown are the property of the respective owner. This list is provided only to show a similarity to the scent as indicates by the word “Type.” © 2016 Gold Star Fragrances, Inc. All rights reserved. FAM5704MA: 03# 1789 Inspired by * 3:AM by Sean John [MA], $4.95, $14.75, $29.00, $56.00. F21101FE: 22# 101 Inspired by * 212 by Carolina Herrera [FE], $4.95, $14.75, $29.00, $56.00. F21351MA: 22# 351 Inspired by * 212 by Carolina Herrera [MA] , $4.95, $14.75, $29.00, $56.00. -

Omarion O Mp3, Flac, Wma

Omarion O mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: O Country: Europe Released: 2005 Style: Rhythm & Blues MP3 version RAR size: 1710 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1439 mb WMA version RAR size: 1972 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 478 Other Formats: MMF MPC FLAC VOX MP4 TTA AIFF Tracklist Hide Credits I Wish 1 Backing Vocals – Omarion, Quintin AneyKeyboards – Corna Boys, Tha*Producer – Corna Boys, Tha* Touch 2 Producer – The Neptunes O 3 Backing Vocals [Additional] – Durrell Babbs*, Eric DawkinsCo-producer – Tank Producer – The Underdogs I'm Tryna 4 Backing Vocals [Additional] – Durrell Babbs*, Eric DawkinsProducer – The UnderdogsProducer [Additional] – Antonio Dixon, Tank Drop That Heater 5 Backing Vocals [Additional] – Omarion, Sean GarrettCo-producer – Sean GarrettProducer – Rodney "Darkchild" Jerkins* Growing Pains 6 Instruments – Marques HoustonProducer – Marques Houston Take It Off 7 Instruments – Cory BoldProducer – Chris Stokes, Cory Bold, Marques Houston, Omarion Never Gonna Let You Go (She's A Keepa) Backing Vocals [Additional] – Charles "Charlie" Crawford*, Jamie VickBass – Carey Drisdom Jr., 8 Carey Drisdom Jr., Joel CampbellFeaturing – Big BoiHorns [Arranger] – Lorenzo L. Johnson Jr.Keyboards [Additional] – Joel CampbellProducer – AllstarSaxophone – Brandon BanksTrombone – Ryan TateTrumpet – Bryan Tate I Know 9 Instruments – Chris "Rawdog" DensonProducer – Ra.W I'm Gon' Change 10 Backing Vocals – Omarion, One ChanceKeyboards – Tha Corna Boys*Producer – Tha Corna Boys*Vocals [Additional] – Pierre Medor In The Dark 11 Co-producer – Chris Stokes, Marques Houston, OmarionInstruments – Kenny "The Wizard" Washington*Producer – Kenny "The Wizard" Washington* Slow Dancin' 12 Instruments – Gil Smith II*, Kowan "Q" Paul*Producer – Gil Smith II*, Kowan "Q" Paul* Fiening You 13 Instruments – Cory BoldProducer – L.T. -

Complete Report

Acknowledgments FMC would like to thank Jim McGuinn for his original guidance on playlist data, Joe Wallace at Mediaguide for his speedy responses and support of the project, Courtney Bennett for coding thousands of labels and David Govea for data management, Gabriel Rossman, Peter DiCola, Peter Gordon and Rich Bengloff for their editing, feedback and advice, and Justin Jouvenal and Adam Marcus for their prior work on this issue. The research and analysis contained in this report was made possible through support from the New York State Music Fund, established by the New York State Attorney General at Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, the Necessary Knowledge for a Democratic Public Sphere at the Social Science Research Council (SSRC). The views expressed are the sole responsibility of its author and the Future of Music Coalition. © 2009 Future of Music Coalition Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 4 Programming and Access, Post-Telecom Act ........................................................ 5 Why Payola? ........................................................................................................... 9 Payola as a Policy Problem................................................................................... 10 Policy Decisions Lead to Research Questions...................................................... 12 Research Results .................................................................................................. -

Racism in the Ron Artest Fight

Flagrant Foul: Racism in "The Ron Artest Fight" by Jeffrey A. Williams* "There's a reason. But I don't think anybody ought to be surprised, folks. I really don't think anybody ought to be surprised. This is the hip-hop culture on parade. This is gang behavior on parade minus the guns. That's what the culture of the NBA has become." - Rush Limbaugh1 "Do you really want to go there? Do I have to? .... I think it's fair to say that the NBA was the first sport that was widely viewed as a black sport. And whatever the numbers ultimately are for the other sports, the NBA will always be treated a certain way because of that. Our players are so visible that if they have Afros or cornrows or tattoos- white or black-our consumers pick it up. So, I think there are al- ways some elements of race involved that affect judgments about the NBA." - NBA Commissioner David Stern2 * B.A. in History & Religion, Columbia University, 2002, J.D., Columbia Law School, 2005. The author is currently an associate in the Manhattan office of Milbank Tweed Hadley & McCloy. The views reflected herein are entirely those of the author alone. I would dedi- cate this piece to shedding tattoo tears. 1 Rush Limbaugh, the Rush Limbaugh Show, Nov. 22, 2004 available at http://www.free republic.com/focus/f-news/1289370/posts. To view footage of the fight, see infra note 42 (col- lecting clips). 2 Michael Lee, NBA Fights to Regain Image; One Year Later, Brawl Leaves a Mark Throughout League, WASHINGTON POST, November 19, 2005 at E01. -

Omarion Ice Box (Remixes) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Omarion Ice Box (Remixes) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop / Funk / Soul Album: Ice Box (Remixes) Country: UK Released: 2007 Style: Contemporary R&B, House MP3 version RAR size: 1162 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1344 mb WMA version RAR size: 1918 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 149 Other Formats: TTA MP1 MP2 AIFF MIDI VOC AA Tracklist Hide Credits Ice Box (DJ Nabs Remix) (Clean) 1 Featuring – Da BratRemix – DJ Nabs Ice Box (DJ Nabs Remix) (Main) 2 Featuring – Da BratRemix – DJ Nabs Ice Box (Slang House Remix) 3 Remix – Slang Ice Box (Mr. Mig Mixshow Extended Remix) 4 Remix – Mr. Mig Ice Box (Nu Soul / Azza Remix) 5 Remix – Azza, Nu Soul Ice Box (Slang House Dub) 6 Remix – Slang Ice Box (Mr. Mig Dub) 7 Remix – Mr. Mig Ice Box (Nu Soul / Azza Dub) 8 Remix – Azza, Nu Soul Credits Producer – Timbaland Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 88697 07968 Ice Box (CD, 88697 07968 Omarion RCA UK 2006 2 Single) 2 T.U.G. Entertainment, 88697 09749 Ice Box (CD, 88697 09749 Omarion Sony Urban Music, Europe 2006 2 Maxi, Enh) 2 Columbia 88697 03063 Ice Box (12", T.U.G. Entertainment, 88697 03063 Omarion US 2006 1-S1 Promo) Sony Urban Music 1-S1 Ice Box (CDr, none Omarion Not On Label none Switzerland 2007 Single, Promo) Ice Box (CDr, 80PG7456 Omarion Sony Urban Music 80PG7456 US 2006 Single, Promo) Related Music albums to Ice Box (Remixes) by Omarion Beyoncé - Irreplaceable Bow Wow & Omarion - Face Off Justin Timberlake Duet With Beyoncé - Until The End Of Time - Club Mixes Faithless - Bombs Justin Timberlake - What Goes Around...Comes Around (Remixes) John Legend featuring Andre 3000 - Greenlight Justin Timberlake - My Love (Remixes) Justin Timberlake - My Love Omarion - 21 Mark Ice & Dillgin - New Slang (Hip Hop Remix) / Version.