Mediterranean Marine Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KEY LARGO Diver Dies Inside the ‘Grove’ Keynoter Staff Was a District Chief with Lake Dangerous

WWW.KEYSNET.COM SATURDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2013 VOLUME 60, NO. 84 G 25 CENTS KEY LARGO Diver dies inside the ‘Grove’ Keynoter Staff was a district chief with Lake dangerous. Three New Jersey Kissimmee, intended to do a County Emergency Medical Fire official, friend did penetration divers died penetration diving penetration dive on their own, A Central Florida fire- Services, near Orlando, and dive, considered most dangerous the Grove in 2007. without a guide. department commander was was with the department for The two men were on a Dorminy told Sheriff’s found dead Friday at the 15 years. Largo Fire Rescue found 2002, with his dive buddy, commercial dive vessel oper- Office Deputy Tony Code Spiegel Grove dive wreck off Dragojevich’s supervisor, Dragojevich’s body just after James Dorminy, 51, Thursday. ated by Scuba Do Dive Co. and Dive Team Leader Sgt. Key Largo after a so-called Deputy Chief Ralph 1:30 p.m. and were making The men were doing a pene- with six other divers Thursday Mark Coleman they attached penetration dive in which a Habermehl, said Dragojevich efforts to remove it. That was tration dive, meaning they afternoon. Although the dive a reel line when they entered diver actually enters the was an experienced diver and expected to take several were inside the 510-foot for- operators and other divers so they would be able to find wreck — considered that he knew Dragojevich hours to complete. mer Navy ship. Penetration reportedly did not intend to their way out. They explored extremely dangerous. was on a dive trip in the Keys. -

Electric Marine Vessels and Aquanaut Crafts

ELECTRIC MARINE VESSELS AND AQUANAUT CRAFTS. [3044] The invention is related to Electro motive and electric generating clean and green, Zero Emission and sustainable marine vessels, ships, boats and the like. Applicable for Submersible and semisubmersible vessels as well as Hydrofoils and air-cushioned craft, speeding on the body of water and submerged in the body of water. The Inventions provides a Steam Ship propelled by the kinetic force of steam or by the generated electric current provided by the steam turbine generator to a magnet motor and generator. Wind turbine provided on the above deck generating electric current by wind and hydroelectric turbines made below the hull mounted under the hull. Mounted in the duct of the hull or in the hull made partial longitudinal holes. Magnet motor driven the rotor in the omnidirectional nacelle while electricity is generating in the machine stator while the turbine rotor or screw propeller is operating. The turbine rotor for propulsion is a capturing device in contrary to a wind, steam turbine or hydro turbine rotor blades. [3045] The steam electric ship generates electricity and desalinates sea water when applicable. [3046] Existing propulsion engines for ships are driven by diesel and gas engines and hybrid engines, with at least one angle adjustable screw propeller mounted on the propeller shaft with a surrounding tubular shroud mounted around the screw propeller with a fluid gap or mounted without a shroud mounted below the hull at the aft. The duct comprises: a first portion of which horizontal width is varied from one side to the other side; and a second portion connected to one side of the first portion and having the uniform horizontal width. -

Malta Fisheries

PROJECT: FAO COPEMED ARTISANAL FISHERIES IN THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN Malta Fisheries The Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture of Malta By: Ignacio de Leiva, Charles Busuttil, Michael Darmanin, Matthew Camilleri. 1. Introduction The Maltese fishing industry may be categorised mainly in the artisanal sector since only a small number of fishing vessels, the larger ones, operate on the high seas. The number of registered gainfully employed full-time fishermen is 374 and the number of vessels owned by them is 302. Fish landings recorded at the official fish market in 1997 amounted to a total of 887 metric tonnes, with a value of approx. Lm 1.5 million (US$4,000,000). Fishing methods adopted in Malta are demersal trawling, "lampara" purse seining, deep-sea long-lining, inshore long-lining, trammel nets, drift nets and traps. The most important commercial species captured by the Maltese fleet are included as annex 1. 2. Fishing fleet The main difference between the full-time and artisanal category is that the smaller craft are mostly engaged in coastal or small scale fisheries. The boundary between industrial and artisanal fisheries is not always well defined and with the purpose of regional standardisation the General Fisheries Council for the Mediterranean (GFCM), at its Twenty-first Session held in Alicante, Spain, from 22 to 26 May 1995, agreed to set a minimum length limit of 15 metres for the application of the "Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas" and therefore Maltese vessels over 15 m length should be considered as industrial in line with this agreement. -

NATURA 2000 SECTORIAL WORKSHOPS (Malta, 26/09/2014 - 03/10/2014)

NATURA 2000 SECTORIAL WORKSHOPS (Malta, 26/09/2014 - 03/10/2014) Workshop Report LIFE+ MIGRATE Conservation Status and potential Sites of Community Interest for Tursiops truncatus and Caretta caretta in Malta (LIFE 11 NAT/MT/1070) Sectorial Workshop Report 1_ _2 LIFE+ Project MIGRATE INDEX 5 0. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 1. OPENING OF THE WORKSHOPS 7 1.1 Official opening and introduction 8 1.2 Presentation of the project results 9 1.3 Panel I: Introducing Natura 2000 11 1.4 Panel II: Natura 2000 in the Mediterranean Context. 15 2. SECTORIAL WORKSHOP – TRANSPORT AND ENERGY 15 2.1 Official opening and introduction 15 2.2 Framework and Case-studies 22 2.2 Discussion of the Natura 2000 Guidelines 29 3. SECTORIAL WORKSHOP – SECURITY AND SAFETY 29 3.1 Official opening and introduction 35 Discussion on the Natura 2000 Guidelines 41 4. SECTORIAL WORKSHOP – FISHERIES 41 4.1 Official opening and introduction 46 4.2 Discussion of the NATURA 2000 Guidelines 49 5. SECTORIAL WORKSHOP – TOURISM 49 5.1 Official opening and introduction 53 5.2 Presentation on the Natura 2000 Guidelines 57 6. SECTORIAL WORKSHOP – RESEARCH, EDUCATION AND CONSERVATION 57 6.1 Official opening and introduction 64 6.2 Presentation on the Natura 2000 Guidelines 66 ANNEX I - SPEAKERS Sectorial Workshop Report 3_ _4 LIFE+ Project MIGRATE 0. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On September 26th and from September 29th to October 3rd of 2014, six workshops were held in Buggiba (Malta), under the venue of the Malta National Aquarium, and, in the last day, on the Nature Trust Headquarters at Marsaxlokk. -

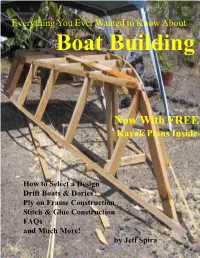

Now with FREE Kayak Plans Inside

Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Boat Building Now With FREE Kayak Plans Inside How to Select a Design Drift Boats & Dories Ply on Frame Construction Stitch & Glue Construction FAQs and Much More! by Jeff Spira Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Boat Building by Jeff Spira Published by: Spira International, Inc. Huntington Beach, California, U.S.A. http://www.SpiraInternational.com Copyright © 2006, by Jeffrey J. Spira All Rights Expressly Reserved This e-book may be printed, copied and distributed freely so long as it is not altered in any way. Selecting a Boat to Build The Style of Boat For Your Needs Before you ever start building a boat, you should first consider what type of boat you want and/or need. I say and/ or, because a lot of people think they want a certain type of boat, due to current styles or some fanciful dream, when they actually should be considering an entirely different design. Let's discuss some of the basics of boat hulls so that you'll be able to look at a hull and figure out how it will perform. Displacement Hulls All boats operating at low speeds are displacement hulls. This includes planing hulls going slow. What defines a displacement hull is that the boat displaces the weight of water equal to the boat's weight (including the weight of the people and cargo inside.) Sailboats, canoes, kayaks, most dories, rowboats, trawlers, and cargo ships are all examples of displacement hulls. For a displacement hull to move through the water it must push water aside as it passes, then after it passes water comes back together to refill fill the space taken up by the hull. -

Her Beautiful Life

Warning: Graphic image of a sea lion bite inside www.pacificfishing.com THE BUSINESS MAGAZINE FOR FISHERMEN n MARCH 2019 Her beautiful life US $2.95/CAN. $3.95 • Halibut catch limits 03 63126 • Gillnets under siege Only pay for the speed you need... Dynamic Routing! SM Lynden’s new mobile app is now available! lynden.com/mobile On time and on budget. At Lynden, we understand that plans change but deadlines don’t. That’s why we proudly offer our exclusive Dynamic Routing system. Designed to work around your unique requirements, Dynamic Routing allows you to choose the mode of transportation – air, sea or land – to control the speed of your deliveries so they arrive just as they are needed. With Lynden you only pay for the speed you need. lynden.com | 1-888-596-3361 IN THIS ISSUE Editor's note Wesley Loy ® Gunning THE BUSINESS MAGAZINE FOR FISHERMEN INSIDE for gillnets Gillnets are a very old form of commercial fishing gear. They’re highly effective for catching salmon and other species. They’re also very good at collecting controversy. Gillnets are banned in some jurisdictions, and stringently regulated elsewhere. Along the Pacific coast, we’ve seen periodic attempts to shut down gillnet- ting. In Alaska a few years ago, activists unsuccessfully pushed a ballot initia- tive to ban commercial setnets in Cook Inlet. In Oregon, voters in 2012 defeated Halibut catch limits • Page 8 a measure to end gillnetting in the Columbia River. Now, we have anti-gillnet bills pending in the Oregon and Washington state legislatures. -

Kalahari Outventures Drift Boat Experience Brochure

Fly Fishing the Orange River Drift Boat Experience FOLLOW US @kalaharioutventures Our Mission As Kalahari Outventures we make it our mission to provide a complete wilderness fly fishing experience, targeting mainly Yellowfish in a section of the Orange River below the Augrabies falls. Drift Boat Experience Drift Boat Fly Fishing Package (5days, 5nights) This exclusive Drift Boat trip covers a 40 km private stretch of the Orange River within the Kalahari Largemouth Yellowfish Conservancy where you will be professionally guided. The river passes through some of the most unspoilt landscapes in South Africa with untouched waters teaming with wild and untamed Yellowfish. *Fly Fishing Only Overview Season: May - OctoBer Duration: 5 Nights, 4 Days fishing Guests: 4 PAX Drift: +/- 40kms Cost : R15 495.00 pp (min 4 pax or we make up group to meet requirements) The Kalahari Outventures Drift Boat Experience is a trip for someone looking to either take a relaxed stress free float down the Beautiful Orange River; or those who would consider themselves as a die hard fisherman. The drift is open to people of all ages and levels of fitness. You will Be professionally guided through beautiful fly water as your guide navigates you downstream for 4 days of fishing for Largemouth and Smallmouth Yellowfish. You will predominantly fish from our specifically designed drift boats rigged with an electric motor and anchors to ensure we can get you onto the best fishing spots. Yellowfish ( Labeobarbus) Yellowfish (scientifically known as Labeobarbus) are a mid-sized ray- finned, scaled fish that is widely distributed throughout Eastern and especially Southern Africa. -

Fast Boat, Dream Boat

Tracking red king crab by Saildrone www.pacificfishing.com THE BUSINESS MAGAZINE FOR FISHERMEN n JULY 2019 Fast boat, dream boat US $2.95/CAN. $3.95 • Record Alaska herring haul 63126 • B.C.’s new PFD requirement Cool Chain... Logistics for the Seafood Industry! From Sea to Serve Lynden’s Cool ChainSM service manages your seafood supply chain from start to nish. Fresh or frozen seafood is transported at just the right speed and temperature to meet your particular needs and to maintain quality. With the ability to deliver via air, highway, or sea or use our temperature-controlled storage facilities, Lynden’s Cool ChainSM service has the solution to your seafood supply challenges. www.lynden.com | 1-888-596-3361 IN THIS ISSUE ® THE BUSINESS MAGAZINE FOR FISHERMEN B.C.’s new PFD requirement • Page 9 Boats and engines • Page 10 Record Alaska herring haul • Page 19 West Coast Dungeness update • Page 20 Tracking red king crab by Saildrone • Page 14 VOLUME XL, NO. 7 • JULY 2019 Pacific Fishing (ISSN 0195-6515) is published 12 times a year (monthly) by Pacific Fishing Magazine. Editorial, Circulation, ON THE COVER: The fishing vessel Fitzcarraldo and Advertising offices at 14240 Interurban Ave S, Ste. 190, Tukwila, WA 98168, U.S.A. Telephone (206) 324-5644. n Subscriptions: One-year rate for U.S., $18.75, two-year $30.75, three-year $39.75; Canadian subscriptions paid in U.S. is hauled over the Chigmit Mountains toward funds add $10 per year. Canadian subscriptions paid in Canadian funds add $10 per year. -

If I Had a Boat

IF I HAD A BOAT BY LUCY LEA TUCKER 66 biglife IF I HAD A BOAT BY LUCY LEA TUCKER biglife 67 IF I HAD A BOAT NEVER TURN DOWN A SPONTANE- OUS ROAD TRIP, PLANE RIDE, OR BOAT OUTING—RULES TO LIVE BY IN MY PLAYBOOK. SO, WHEN FRIENDS INVITE ME TO JOIN THEM ON A DRIFT BOAT DOWN THE ROARING FORK RIVER WITH ONE OF THE BEST FLY FISHING GUIDES IN THE VALLEY—YOU CAN BET THAT I SAY “YES.” AFTER A BUSY WORK WEEK, A SPUR-OF- THE-MOMENT OUTDOOR ADVENTURE WAS THE EXACT ESCAPE I NEEDED. BEFORE HITTING THE RIVER, WE PICK UP OUR GUIDE, BRANDON, AT THE BOULDER BOAT WORKS WAREHOUSE IN CARBONDALE, WHERE HIS BOAT WAS CUSTOM DESIGNED TO SPEC, A STONE’S THROW FROM THE ‘PUT IN’ ON THE FORK. PHOTOGRAPHY: JORDAN CURET JORDAN PHOTOGRAPHY: 68 biglife hecking out the an investment than other shallow waters. With Boul- clean lines and boats, the value is in the der Boats, you don’t have C nice aesthetic timeless look and feel, to work hard to slow down feel of the sand shade as well as its durability. on the river, to hold clients hulls in the warehouse, I It’s a hand-up from rafts, in sweet spots, or to fish ask, “What’s so special fiberglass, and aluminum favored stretches.” about these boats?” Boat drift boats. It’s easy to row As it turns out, boat- builder, Matt Clemente, and it’s the lightest, safest, making is an intricate art grins as he gazes over best-handling drift boat on form. -

PZ Fishing Boats Boat Name Boat Details Aaltje Adriaantje PZ 198 Aaltje Adriaantje

PZ Fishing Boats Boat Name Boat Details Aaltje Adriaantje PZ 198 Aaltje Adriaantje. Beam Trawler. Steel hull. 28.6m long, 700hp Stork engine, built 1967. (Smart:29 says it was built in Holland in 1970). Named by previous owners after two little Dutch girls. Stevenson Fleet 2001. List: 431 Chappell; 3660 Lenton. References: Stevenson & Perry 2001:143. NA 80, 3642. Model boat made by Donald Smith & Son, Kintore, Aberdeen andf lent by Billy Stevenson to show alongside the exhibition, Carl Cheng Ghost Ships at Newlyn Art Gallery 11/10/1997-8/11/1997. Abner (Missing PZ No) Abner. Crew 1851 census: William Jacko, M, 33 (Master); Nicholas Willis, M, 29; John Blewet, M, 40; John Lobb, U, 54; William Wilkins, U, 22; Benjamin Downing, U, 34; James Pollard, U,34. Reference: 1851 census. ABS PZ 203 ABS. Beam Trawler. Steel hull. 25.28 long, 535 Deutz engine. Built 1960 as A490 Camperdown. Renamed PZ 203 ABS in 1969. Initials of Anthony Bryan Stevenson. In 2007 renamed TO50 Emma Louise Stevenson Fleet 2001. List: 431 Chappell; 3660 Lenton. References: Perry 2001:143. NA 1133 (photo). Acacia PZ 319 Acacia. Name changed from PZ 319 Girl Lilian to PZ 319 Acacia. Ben Ridge Jn bought PZ319 Acacia previously PZ 319 Girl Lilian in 1936. Kerney 'Cake' Payne was skipper. Commandeered by the Admiralty for the duration of WW2. Owner Richard Henry Richards who sailed it with Henry and Freddy Richards (JF). The Richards were kin of Jenny Fitton and the family have a painting of this boat. See 113. Operating at Newlyn around 1932 and later. -

Review of the Maltese Fishery Statistical System and Options for Its Improvement

Review of the Maltese Fishery Statistical System and options for its improvement. Salvatore R. Coppola Fishery Resources Division National Aquaculture Centre, Fort San Lucjan, Marsaxlokk FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS La Valletta, November, 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Executive summary 1 1. Introduction 2 2. The present situation 2 3. Introductory considerations 3 4. Objectives 3 5. The expected data structure of the proposed system 4 6. The proposed programme 5 7. The system design and its implementation plan 8 References 11 Appendix 1 – People participating in this task 14 Appendix 2 – The area stratification 15 Appendix 3 – Malta - Statistical system – Fishing area codes 17 Appendix 4 – Malta - Statistical system – Fishing vessels frame Main data elements 20 Appendix 5 – Malta - Statistical system – Catch and effort survey Main data elements 21 Appendix 6 – Malta – Fishing zone definition (artisanal fishery) Appendix 7 – Extract 23 Executive summary The Government of Malta avows that appropriate fishery and aquaculture management passes through an accurate and timely control of the phenomena influencing the sector (fishery and aquaculture statistics in the broad sense). The Government also recognises the need to reorganise the Fishery Department to better respond to the above requirements. During the reorganisation process the Government took the opportunity of the existing sub-regional FAO Project "COPEMED" to seek technical assistance in building up national capabilities for data collection and information systems. Immediate consultations held with FAO and COPEMED resulted in a project activity supported by the Project aiming at directly assisting the Government of Malta to build up adequate infrastructures for the establishment of a sound national data collection and information system for fishery and aquaculture. -

Turbine Machines Are Applicable for Speeding and Flying Objects

APPLICABILITY AND COMPATIBLE. [1905] Turbine machines are applicable for speeding and flying objects, vehicles and machines for generating electric current and for propulsion of the electric vehicle, vessels or craft. Unlike stationary turbine machines the machines mounted on a speeding object generates electric current for the vehicle electric supply. While the vehicle moving through the ambient air or water is the generator of friction around the object forcing itself through matter. Whereby friction of wind is obtained for driving the turbine oriented in the head wind direction or ducting the flow of fluid to the turbine machine. A marine vessel speeding on the body of water has the advantage to utilize both flowing matter of water and wind when speeding. motorized and non-motorized vehicles speeding and flying objects, vehicles, crafts. Applicable for vessels speeding on a body of water and vessels submerged in the body of water. [1906] The inventions are Applicable for, Vehicle – non-living means of transportation provided with the inventions. Vehicles are most often man-made, although some other means of transportation. Know the comprehensive flow of mixed heterogenous traffic from paddled vehicles, pushed subjects on wheels to flying objects worn as a suite. Examples include icebergs and floating tree trunks. A list of vehicles is given beneath. Aero Sani, Airship. All-terrain vehicle. Amphibious all-terrain vehicle. Amphibious vehicle. Autogiros. Automobile. Auto rickshaw. Balloon. Bathyscaphe. Bicycle. Blimp. Boat. Bus. Cable car. Catamaran. Canoe. (Coach (bus). Coach carriage). Cycle rickshaw. Dandy horse. Deep Submergence Vehicle. Diving bell. Diving chamber. Dog sled. Draisine. Electric vehicle. Fixed-wing aircraft.