Sample Chapter Uncorrected Page Proof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bog Bodies & Their Biochemical Clues

May 2018 cchheemmiissin Auttstrrraliayy Bog bodies & their biochemical clues chemaust.raci.org.au • Spider venoms as drenching agents • Surface coatings from concept to commercial reality • The p-value: a misunderstood research concept SBtioll ghe rbe odies in the hereafter n 13 May 1983, the Bog bodies such as Tollund Man partially preserved head provide a fascinating insight into of a woman was Odiscovered buried in biochemical action below the ground. peat at Lindow Moss, near Wilmslow in Cheshire, England. Police BY DAVE SAMMUT AND suspected a local man, Peter Reyn- Bardt, whose wife had gone missing CHANTELLE CRAIG two decades before .‘It has been so long, I thought I would never be Toraigh Watson found out’, confesse dReyn- Bardt under questioning. He explained how he had murdered his wife, dismembered her body and buried the pieces near the peat bog. Before the case could go to trial, carbon dating of the remains showed that the skull was around 17 centuries CC-PD-Mark old. Reyn- Bardt tried to revoke his confession, but was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment . Lindow Woman and other ‘bog bodies’, as they have come to be known, are surprisingly common. Under just the right set of natural conditions, human remains can be exceptionally well preserved for extraordinarily long periods of time. 18 | Chemistry in Australia May 2018 When bog water beats bacteri a Records of bog bodies go back as far as the 17th century, with a bod y discovered at Shalkholz Fen in Holstein, Germany. Bog bodies are most commonly found in northwestern Europe – Denmark, the Netherlands, Ireland, Great Britain and northern Germany. -

Human Remains, Museum Space and the 'Poetics of Exhibiting'

23 — VOLUME 10 2018 UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS JOURNAL Human remains, museum space and the ‘poetics of exhibiting’ Kali Tzortzi Abstract The paper explores the role of the design of museum space in the chal- lenges set by the display of human remains. Against the background of ‘embodied understanding’, ‘multisensory learning’ and ‘affective distance’ and of contextual case studies, it analyses the innovative spa- tial approach of the Moesgaard Museum of the University of Aarhus, which, it argues, humanizes bog bodies and renders them an integra- tive part of an experiential, embodied and sensory narrative. This allows the mapping of spatial shifts and new forms of engagement with human remains, and also demonstrates the role of university museums as spaces for innovation and experimentation. 24 — VOLUME 10 2018 UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS JOURNAL Introduction and research question This paper aims to explore the issue of the respectful presentation of human physical remains in contextual exhibitions by looking at the role of museum space in the challenges set by their display, with particular reference to the contribution of experimentation in the university museum environ- ment. The debate raised by the understanding that human remains “are not just another artefact” (stated by CASSMAN et al. 2007, in GIESEN 2013, 1) is extensively discussed in the literature, and increasingly explored through a range of museum practices. In terms of theoretical understanding, authors have sought to acquire an overall picture of approaches towards the care of human remains so as to better understand the challenges raised. For example, among the most recent publica- tions, O’Donnabhain and Lozada (2014) examine the global diversity of attitudes to archaeological human remains and the variety of approaches to their study and curation in different countries. -

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

Bog Bodies of Norway: in Search of Nordic Noir Alphaeus Talks1

Issue 51 Bog Bodies of Norway: In search Of Nordic Noir Alphaeus Talks1 1 Dept of Archaeology, University of York, King’s Manor, Exhibition Sq., York, YO1 7EP [email protected] 2 Heritage Technology, 5 Huntington Road, York, YO31 8RA [email protected] Introduction Since their discovery in the 17th century, bog bodies have gripped the imagination with their ability to tell fascinating, mysterious and macabre stories of our past, due to their remarkable preserved states (van der Sanden 1996, 19); their skin dyed dark in the peatlands of Northern Europe where the sphagnum moss produces a substance, called sphagnan, which preserves the bodies of the deceased (Asing and Lynnerup 2007, 278). By studying these bodies, archaeologists are provided with insights into people’s lives, including how they died, their appearance, illnesses, environment and diet. Bog bodies have been discovered in many places across Northern Europe, but whether there are any “bog bodies proper” in Norway is a controversial topic. This is largely due to the limited data available from excavation (Nordeide and Thun 2013, 200), as well as lost archived bodies (van der Sanden 1996, 20). Norway’s bog bodies are therefore a mystery which needs further investigation. The Bog Bodies of Norway Figure 1: Map of bog bodies discovered in Norway. 18 Issue 51 Arguably around fourteen bog bodies have been discovered in Norway, as shown in Figure 1. However, there is a debate about this number, with Turner-Walker and Peacock proposing fifteen (2008, 151), Brothwell and Gill-Robinson only two (2001, 121) and Dieck suggesting ten (Aufdeheide 2010, 176). -

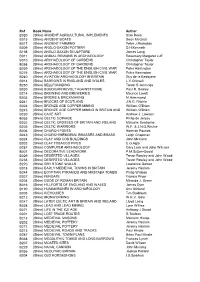

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

Irish Identity in Seamus Heaney Selected Poems

Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8435 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.13, 2015 Irish Identity in Seamus Heaney Selected Poems Hawnaz Ado Dept. of English Language and Literature,Istanbul Aydin University, Besyol Mah. ,Inönü Cad. No. 38,Küçükçekmece, Istanbul, Istanbul TURKEY Abstract This paper aims the thematic analysis of Irish identity in the noble winner's poems, Seamus Heaney. Through the history of Ireland and its people how they suffered under the British Imperialism beside the sectarian conflicts that held in Ireland. Heaney's Bog poems search about the origins of Irish identity, through his first four collection, Death of the Naturalist, Door into the Dark, Wintering Out, and North. The selected poems of these four collections are like a chain for the bog poems of Heaney which is about bog people as Heaney used them as a symbol to Irish identity. Keywords: Identity, Irish identity , Bog poems , British Imperialism 1. Introduction The matter of Irish political conflict raised from the early nineteenth century till 1922, this is for the Republican of Ireland while in the Northern Ireland the conflict continued between the two communities Catholic and Protestant. As the idea that cultural'' identity is at the heart of the Northern Ireland crisis’’ (Lundy and Mac Polin 1992: 5) became a part of traditional wisdom. Going through discussing the history of Ireland especially Northern Ireland and the issue of its identity limiting to specific by taking from the land of conflict and troubles Seamus Haney as the spokesman of identity in Northern Ireland. -

(Netherlands) (.Institute for Biological Archaeology

Acta Botanica Neerlandica 8 (1959) 156-185 Studies on the Post-Boreal Vegetational History of South-Eastern Drenthe (Netherlands) W. van Zeist (.Institute for Biological Archaeology , Groningen ) (received February 6th, 1959) Introduction In this paper the results of some palynological investigations of peat deposits in south-eastern Drenthe will be discussed. The location of the be discussed is indicated the of 1. This profiles to on map Fig. which is modified of the map, a slightly copy Geological Map (No. 17, sheets 2 and No. 2 and of the soils in the 4, 18, 4), gives a survey Emmen district. Peat formation took place chiefly in the Hunze Urstromtal, which to the west is bordered by the Hondsrug, a chain of low hills. It may be noted that the greater part of the raised bog has now vanished on account of peat cutting. In the eastern part of the Hondsrug fairly fertile boulder clay reaches the surface, whereas more to the in west general the boulder clay is covered by a more or less thick deposit of cover sand. Fluvio-glacial deposits are exposed on the eastern slope of the Hondsrug. Unfortunately, no natural forest has been left in south-eastern the in Drenthe. Under present conditions climax vegetation areas the with boulder clay on or slightly below surface would be a Querceto- Carpinetum subatlanticum which is rich in Fagus, that in the cover sand the boulder areas—dependent on the depth of clay—a Querceto roboris-Betuletum or a Fageto-Quercetum petraeae ( cf Tuxen, 1955). In contrast to the diagrams from Emmen and Zwartemeer previous- ly published (Van Zeist, 1955a, 1955b, 1956b) which provide a survey of the vegetational history of the whole Emmen district, the diagrams from Bargeroosterveld and Nicuw-Dordrecht have a more local character. -

Exploring the Potential of the Strontium Isotope Tracing System in Denmark

Danish Journal of Archaeology, 2012 Vol. 1, No. 2, 113–122, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21662282.2012.760889 Exploring the potential of the strontium isotope tracing system in Denmark Karin Margarita Frei* Danish Foundation’s Centre for Textile Research, CTR, SAXO Institute, Copenhagen University, Copenhagen, Denmark (Received 1 October 2012; final version received 14 November 2012) Migration and trade are issues important to the understanding of ancient cultures. There are many ways in which these topics can be investigated. This article provides an overview of a method based on an archaeological scientific methodology developed to address human and animal mobility in prehistory, the so-called strontium isotope tracing system. Recently, new research has enabled this methodology to be further developed so as to be able to apply it to archaeological textile remains and thus to address issues of textile trade. In the following section, a brief introduction to strontium isotopes in archaeology is presented followed by a state-of-the- art summary of the construction of a baseline to characterize Denmark’s bioavailable strontium isotope range. The creation of such baselines is a prerequisite to the application of the strontium isotope system for provenance studies, as they define the local range and thus provide the necessary background to potentially identify individuals originating from elsewhere. Moreover, a brief introduction to this novel methodology for ancient textiles will follow along with a few case studies exemplifying how this methodology can provide evidence of trade. The strontium isotopic system the strontium isotopic signatures are not changed in – from – Strontium is a member of the alkaline earth metal of a geological perspective very small time spans, due to Group IIA in the periodic table. -

The Danish Bog Bodies and Modern Memory," Spectrum: Vol

Recommended Citation Price, Jillian (2012) "Accessing the Past as Landscape: The Danish Bog Bodies and Modern Memory," Spectrum: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholars.unh.edu/spectrum/vol2/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals and Publications at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spectrum by an authorized editor of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spectrum Volume 2 Issue 1 Fall 2012 Article 2 9-1-2012 Accessing the Past as Landscape: The Danish Bog Bodies and Modern Memory Jillian Price University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/spectrum Price: Accessing the Past as Landscape: The Danish Bog Bodies and Modern Accessing the Past as Landscape: The Danish Bog Bodies and Modern Memory By Jillian Price The idea of “place-making” in anthropology has been extensively applied to culturally created landscapes. Landscape archaeologists view establishing ritual spaces, building monuments, establishing ritual spaces, organizing settlements and cities, and navigating geographic space as activities that create meaningful cultural landscapes. A landscape, after all, is “an entity that exists by virtue of its being perceived, experienced, and contextualized by people” (Knapp and Ashmore 1999: 1). A place - physical or imaginary - must be seen or imagined before becoming culturally relevant. It must then be explained, and transformed (physically or ideologically). Once these requirements are fulfilled, a place becomes a locus of cultural significance; ideals, morals, traditions, and identity, are all embodied in the space. -

The Grauballe Man Les Corps Des Tourbières : L’Homme De Grauballe

Technè La science au service de l’histoire de l’art et de la préservation des biens culturels 44 | 2016 Archives de l’humanité : les restes humains patrimonialisés Bog bodies: the Grauballe Man Les corps des tourbières : l’homme de Grauballe Pauline Asingh and Niels Lynnerup Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/techne/1134 DOI: 10.4000/techne.1134 ISSN: 2534-5168 Publisher C2RMF Printed version Date of publication: 1 November 2016 Number of pages: 84-89 ISBN: 978-2-7118-6339-6 ISSN: 1254-7867 Electronic reference Pauline Asingh and Niels Lynnerup, « Bog bodies: the Grauballe Man », Technè [Online], 44 | 2016, Online since 19 December 2019, connection on 10 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/techne/1134 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/techne.1134 La revue Technè. La science au service de l’histoire de l’art et de la préservation des biens culturels est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Archives de l’humanité – Les restes humains patrimonialisés TECHNÈ n° 44, 2016 Fig. 1. Exhibition: Grauballe Man on display at Moesgaard Museum. © Medie dep. Moesgaard/S. Christensen. Techne_44-3-2.indd 84 07/12/2016 09:32 TECHNÈ n° 44, 2016 Archives de l’humanité – Les restes humains patrimonialisés Pauline Asingh Bog bodies : the Grauballe Man Niels Lynnerup Les corps des tourbières : l’homme de Grauballe Abstract. The discovery of the well-preserved bog body: “Grauballe Résumé. La découverte de l’homme de Grauballe, un corps Man” was a worldwide sensation when excavated in 1952. -

Development Management Policies and Designations Addendum (Proposed Main Modifications)

A fairer city Salford City Council Publication Salford Local Plan: Development Management Policies and Designations Addendum (Proposed Main Modifications) Draft for approval (January 2021) This document can be provided in large print, Braille and digital formats on request. Please telephone 0161 793 3782. 0161 793 3782 0161 000 0000 Contents PREFACE ............................................................................................................................................. 4 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 9 CHAPTER 3 PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................... 14 • Strategic objective 10 ..................................................................................... 14 CHAPTER 4 A FAIRER SALFORD ........................................................................................................ 15 Policy F2 Social value and inclusion............................................................................. 16 CHAPTER 8 AREA POLICIES ............................................................................................................... 18 Policy AP1 City Centre Salford ............................................................................................. 19 CHAPTER 12 TOWN CENTRES AND RETAIL DEVELOPMENT ............................................................. 24 Policy TC1 Network of designated centres .................................................................... -

R Sites Phd Thesis 2016.Pdf

Collapse, Continuity, or Growth? Investigating agricultural change through architectural proxies at the end of the Bronze Age in southern Britain and Denmark Rachel Leigh Sites Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology The University of Sheffield October 2015 Abstract At the end of the Bronze Age in Europe, new iron technologies and the waning of access to long-distance exchange routes had consequences for social organization, creating changes in social priorities. There is a recursive relationship between the political structure, exchange, and agricultural production, as each informs the other; what, then, was the impact of social reorganization on agricultural production? Through an investigation of domestic architecture, using dwellings, pits, and post-structures as proxies for production and consumption, this study explored a model focused on the changes in energy invested in domestic architecture within and between settlements from the Middle Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age to better understand the impact of socio-technical change on agricultural production in southern Britain and Denmark. Changes in productive (dwellings) and consumptive (pits and post-structures) architecture track a potential measure of agricultural production, demonstrating directly the effect of the wide sweeping social and economic changes, whether of decline, continuity, or growth, on agricultural activities. If growth or even continuity is present in agricultural production during the final years of the Bronze Age, how can we account for it? By relating the changes in area and volume provided by domestic structures to energy, we can compare the effort expended on productive and consumptive architecture between settlements, constructing a geography of production that allows for further consideration of inter-settlement interaction.