Disarray Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church

Andrews University Seminary Student Journal Volume 1 Number 2 Fall 2015 Article 3 8-2015 Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church John Reeve Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/aussj Part of the Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Reeve, John (2015) "Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church," Andrews University Seminary Student Journal: Vol. 1 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/aussj/vol1/iss2/3 This Invited Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andrews University Seminary Student Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andrews University Seminary Student Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1-15. Copyright © 2015 John W. Reeve. FUTURE VIEWS OF THE PAST: MODELS OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE EARLY CHURCH JOHN W. REEVE Assistant Professor of Church History [email protected] Abstract Models of historiography often drive the theological understanding of persons and periods in Christian history. This article evaluates eight different models of the early church period and then suggests a model that is appropriate for use in a Seventh-day Adventist Seminary. The first three models evaluated are general views of the early church by Irenaeus of Lyon, Walter Bauer and Martin Luther. Models four through eight are views found within Seventh-day Adventism, though some of them are not unique to Adventism. -

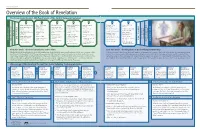

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

English Catholic Eschatology, 1558 – 1603

English Catholic Eschatology, 1558 – 1603. Coral Georgina Stoakes, Sidney Sussex College, December, 2016. This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge. Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. At 79,339 words it does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the History Degree Committee. Abstract Early modern English Catholic eschatology, the belief that the present was the last age and an associated concern with mankind’s destiny, has been overlooked in the historiography. Historians have established that early modern Protestants had an eschatological understanding of the present. This thesis seeks to balance the picture and the sources indicate that there was an early modern English Catholic counter narrative. This thesis suggests that the Catholic eschatological understanding of contemporary events affected political action. It investigates early modern English Catholic eschatology in the context of proscription and persecution of Catholicism between 1558 and 1603. -

The Great Apostasy

Theology Corner Vol. 38 – April 8th, 2018 Theological Reflections by Paul Chutikorn - Director of Faith Formation “How Do I Defend the Faith Against Mormons? (Part 1)” Have you ever been approached by Mormon missionaries coming to your door and talking about why it is that the Catholic Church is not the true faith? I know I have. Knowing your faith is important in these situations so you can dispel any misunderstandings about Catholicism. As always, you have to approach them with charity, otherwise debating with them would be pointless. In addition to knowing your faith pretty well, it is also beneficial to know a few things about that they believe so that you understand what it is that we absolutely cannot accept due to logic, scripture, and Church teaching throughout the ages. There are a few major errors to address about Mormonism, and the one that I will address today is what they would refer to as “The Great Apostasy.” As a way for them to convince us that the Catholic Church is no longer authoritative is by mentioning the theory that it became entirely corrupted after the death of the last apostle. They believe that the apostles were the only ones who truly preached the truth that Jesus handed down to them, and after the last one died (John around 100AD) the faith became “apostate” or abandoned. According to Mormonism, this apostasy lasted until the 1800’s when Joseph Smith restored the faith. The first issue with this theory is that there is no historical evidence whatsoever for there ever being a complete universal apostasy. -

A Response to the Mormon Argument of the Great Apostasy

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 4-16-2021 The Not-So-Great Apostasy?: A Response to the Mormon Argument of the Great Apostasy Rylie Slone Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the History of Christianity Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons SENIOR THESIS APPROVAL This Honors thesis entitled The Not-So-Great Apostasy? A Response to the Mormon Argument of the Great Apostasy written by Rylie Slone and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion of the Carl Goodson Honors Program meets the criteria for acceptance and has been approved by the undersigned readers. __________________________________ Dr. Barbara Pemberton, thesis director __________________________________ Dr. Doug Reed, second reader __________________________________ Dr. Jay Curlin, third reader __________________________________ Dr. Barbara Pemberton, Honors Program director Introduction When one takes time to look upon the foundational arguments that form Mormonism, one of the most notable presuppositions is the argument of the Great Apostasy. Now, nearly all new religious movements have some kind of belief that truth at one point left the earth, yet they were the only ones to find it. The idea of esoteric and special revealed knowledge is highly regarded in these religious movements. But what exactly makes the Mormon Great Apostasy so distinct? Well, James Talmage, a revered Mormon scholar, said that the Great Apostasy was the perversion of biblical truth following the death of the apostles. Because of many external and internal conflicts, he believes that the church marred the legitimacies of Scripture so much that truth itself had been lost from the earth.1 This truth, he asserts, was not found again until Joseph Smith received his divine revelations that led to the Book of Mormon in the nineteenth century. -

Grasping the Great End Time Deception: Understanding and Embracing Jesus' Warning to Watch and Pray

Grasping the Great End Time Deception: Understanding and Embracing Jesus’ Warning to Watch and Pray Key Passage: “Watch out that no one deceives you.”—Matthew 24:4 (5, 10-11, 23-24) The Greek word for “deception” means to cause to roam from safety, truth, or virtue:--go astray, deceive, err, seduce, wander, be out of the way. Paul’s warning to the Church: Another Jesus, a different spirit, the devil in disguise “For if someone comes to you and preaches a Jesus other than the Jesus we preached, or if you receive a different spirit from the Spirit you received, or a different gospel from the one you accepted, you put up with it easily enough. For such people are false apostles, deceitful workers, masquerading as apostles of Christ. And no wonder, for Satan himself masquerades as an angel of light. It is not surprising, then, if his servants also masquerade as servants of righteousness.”—2 Corinthians 11:3-4, 13-15 Point of Truth: The deception will be disguised. False teachers and Satan himself will come with a mask on, disguised as the Light and Truth. Many who were once believers will be deceived and turn away from true faith in Christ. Ø Understanding the End-Time Deception I. False Prophets and the False Teaching: Apostasy and the Anti-Christ A. The Warning: False Prophets and Teachers Will Rise From Within the Church Ø Peter warns about false prophets and teachers in the Church deceiving many and giving a bad name to true Christian faith: “But there were also false prophets among the people, just as there will be false teachers among you. -

Ecce Fides Pillar of Truth

Ecce Fides Pillar of Truth Fr. John J. Pasquini TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication Foreword Introduction Chapter I: The Holy Scriptures and Tradition Where did the Bible come from? Would Jesus leave us in confusion? The Bible alone is insufficient and unchristian What Protestants can’t answer! Two forms of Revelation What about Revelation 22:18-19? Is all Scripture to be interpreted in the same way? Why was the Catholic Church careful in making Bibles available to individual believers? Why do Catholics have more books in the Old Testament than Protestants or Jews? Chapter II: The Church Who’s your founder? Was Constantine the founder of the Catholic Church? Was there a great apostasy? Is the Catholic Church the “Whore of Babylon”? Who founded the Church in Rome? Peter, the Rock upon which Jesus built his Church! Are the popes antichrists? Why is the pope so important? Without the popes, the successors of St. Peter, there would be no authentic Christianity! Why is apostolic succession so important? The gates of hell will not prevail against it! The major councils of the Church and the assurance of the true faith! Why is there so much confusion in belief among Protestants? What gave rise to the birth of Protestantism? Chapter III: Sacraments Are sacraments just symbols? What do Catholics mean by being “born again” and why do they baptize children? Baptism by blood and desire for adults and infants Does baptism require immersion? Baptism of the dead? Where do we find the Sacrament of Confirmation? Why do Catholics believe the Eucharist is the -

Amillennialism David J

Criswell Tabernacle A Defense of Reformed Amillennialism David J. Engelsma Response to the editorial, "Jewish Dreams" (the Standard Bearer, Jan. 15, 1995), has made clear how deep and entrenched are the inroads of postmillennialism into Reformed circles. The editorial, written at the beginning of a new year, reminded Reformed Christians that our only hope, according to the Bible, is the second coming of the Lord Jesus. It sketched in broad outline the traditional, creedal Reformed conception of the last days: abounding lawlessness; widespread apostasy; the Antichrist; and great tribulation for the true church. It gave a warning against the false hope that is known as postmillennialism, quoting a Reformed creed that condemned "Jewish dreams that there will be a golden age on earth before the Day of Judgment." Against this Reformed doctrine of the endtime with its condemnation of postmillennialism have come vehement objections. The objections arise from conservative Reformed and Presbyterian men and churches. One objector asked for a defense of Amillennialism from Scripture. He also confidently asserted that the number of Reformed Amillennialists is steadily decreasing, suggesting that the reason for this is the irrefutable arguments of the postmillennialists. It is true that the postmillennialists are very vocal and aggressive in promoting their theory of the last days. Nor is this true only of those associated with the movement known as "Christian Reconstruction." Also the men of the influential Banner of Truth publishing group vigorously and incessantly push postmillennialism, usually in connection with their expectation of a coming great revival of Christianity. It is also true that there is little or no defense of Amillennialism in the Reformed press. -

An Evaluation of Rapture Theology

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY JOHN W. RAWLINGS SCHOOL OF DIVINITY An Evaluation of Rapture Theology A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Rawlings School of Divinity in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in Biblical Studies by Steven D. Smith Lynchburg VA December 14, 2020 THESIS APPROVAL SHEET RAWLINGS SCHOOL OF DIVINITY ___________________________________ GRADE ___________________________________ THESIS MENTOR ___________________________________ READER ___________________________________ ii Abstract In the realm of scholarly debates regarding eschatology, a prominent divisive topic is the Rapture. Entire books and articles elaborate on the biblical support for and against the role that the Rapture plays within pretribulationism, midtribulationism, and posttribulationism. Such works contain the ongoing clash between interpreters, often with each side claiming that the same passages constitute absolute proof of their respective belief systems. Arguments frequently include the possibility of a seven-year tribulation, an antichrist, and a Rapture: terms not found in the book of Revelation and therefore difficult to explain. A central question that continues to draw a line between scholars is when the Rapture will occur. However, since all prominent theories are not without fault, perhaps the central question should revert to if there is a Rapture. This thesis examines the development and exegesis of modern Rapture theologies. This study reveals that advocates of the Rapture often use inconsistent and unsound methods to arrive at their eschatological conclusions, including distorting the order of passages, using erroneous calculations, and, most of all, reading into verses that which is neither written nor implied. Such attempts to understand the mystery behind potential end-times prophecy causes some scholars to attach confusing passages to a future seven-year tribulation and an associated Rapture. -

The Mark of T the Mark of the Beast

Family Bible Studies - 26 page 1 What the Bible says about – TheThe MarkMark ofof tthehe BeastBeast SCRIPTURE READING: REVELATION 13 AND 14 In Revelation 13 and 14, an issue is sharply drawn between God and the leopard beast. Religion and government will cooperate in forcing the “mark” of the beast upon the world. God’s people, though small in number, comparatively speaking, will stand out in definite distinction from the world in general. It will be God’s last great test of loyalty, and His remnant people will stand in the spirit and faith of Elijah and John the Baptist. As the second coming of Christ approaches, no one can escape the issue. Everyone must decide. Satan will make war on God’s people; but God will be with them and will come in glory to deliver them and reward them, along with the faithful of all ages. 1 - WHO IS THE LEOPARD BEAST OF REVELATION 13? The leopard beast represents the same power as the little horn of Daniel 7. And this power is papal Rome. The following will make this clear. Please look up the following texts: 1. It came up out of the sea (Revelation 13:1) or among mul- titudes (Revelation 17:15). The little horn came up among the ten kingdoms of Europe. The leop- ard beast came up “out of the sea,” which means that it arose among many peoples. Thus the two correspond here. 2. Like the “great red dragon,” it had seven heads and ten horns (Revelation 13:1; 12:3). Both the leopard beast and the great red dragon of your last lesson have seven heads and ten horns, identifying them both as Roman. -

THE ANTICHRIST the Final World Ruler 3/26/06 PM 4/02/06 PM 1

THE ANTICHRIST The Final World Ruler 3/26/06 PM 4/02/06 PM 1. Descriptions From The Book Of Daniel a. Daniel 7 The overview of world empires OVERHEADS 7 He is a part of the last beast 8 The little horn uproots 3 other horns It has the eyes of a man It has a mouth uttering great boasts 11 Boastful words 21 The horn was waging war with the saints and overpowering them until the saints of God take possession of the kingdom. 24 The 10 horns are 10 kings Another horn will subdue 3 of the kings 25 He will speak out against the Most High and wear down the saints of the Holy One. He will intend to make alterations in times and law. The saints are given into his hand for 3 ½ years. 26-27 He will be annihilated by God who will set up His own everlasting kingdom which is given to His people. b. Daniel 8 This chapter was both fulfilled by Antiochus Epiphanies and prefigures the prophesied Antichrist. 8:17, 19, 23 The prophecy goes to the latter days. 9 Small, but becomes great Moves south, east and into the beautiful land 10 Destroys the Jews cf vv. 12, 24 11 Magnifies himself as equal with God Removes sacrifices and destroys temple 12 Hates truth 23 Insolent and skilled in speech 24 Power beyond his own cf v. 22 Revelation 13:2 Will destroy and prosper cf Revelation 13:7 25 Shrewd and causes deceit to succeed. Cf 2 Thessalonians 2:9-10 Magnifies himself cf 2 Thessalonians 2:4; Revelation 13:5 He will create a false sense of peace cf 1 Thessalonians 5:3 He will oppose the Prince of princes cf Revelation 19:19 He will be broken without human agency. -

Jude: Pure Dynamite in a Small Package Winter 2012

Pure Dynamite in a SSmmaallll PPaacckkaaggee Zechariah 4:6 (NKJV) 'Not by might nor by power, but by My Spirit,' says the Lord of hosts. Jude: Pure Dynamite In A Small Package Winter 2012 The Book of Jude, though just 25 verses long, is one of the most powerful books in the Bible. It is written for our generation today, upon whom the end of the ages is come. While Acts chronicles the beginning of the Church and the acts of the Apostles, Jude chronicles the end of the Church and the acts of the apostates. This is the only book in the Bible dedicated entirely to the great apostasy. The same heresies pointed out in Jude appear to be actively working in our society, and could be laying the foundation for the rampant apostasy of the Tribulation period... Table of Contents PAGE 1. Background of the Book of Jude………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 . Apostasy…………………………………………………………………………….…………………………………….…3 2. Assurance for the Believer (Jude 1-2)…………………………………………………………………………………………………....5 . Called-Sanctified-Preserved………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 3. Contenders and Pretenders (Jude 3-4)…………………………………………………………………………………………………8 . What Contending Means………………………………….…………………………………………………………………....9 . The Marks of an Apostate…………………………………………………………………………………………….. ..13 4. Remember What I Told You Not to Forget (Jude 5)……………………………………………………………………. ..14 . Old Testament Typology…………………………………………………………………………………………….. ..16 5. The Nephillim Conspiracy (Jude 6)……………………………………………………………………………………….. ..18 . Two Views of the B’Nai Elohim…………………………………………………………………………………………… 22 . The Stratagems of Satan – The Power Behind the Persecution…………………………………………………. ..24 6. Remembering Sodom and Gomorrah (Jude 7)……………………………………………………………………………………..…25 7. Ancient Sins Reappear (Jude 8)………………………………………………………………………………………………….....29 8. A Rumble in the Heavenlies (Jude 9-10)……………………………………………………………………………………….…33 . A Possibility: The Future Role of Moses……………………………………………………………………………………….…35 9. Three Men and a Warning (Jude 11)…………………………………………………………………………………………..…39 .