China's Policy on Dams at the Crossroads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mekong Tipping Point

Mekong Tipping Point Richard Cronin Timothy Hamlin MEKONG TIPPING POINT: HYDROPOWER DAMS, HUMAN SECURITY AND REGIONAL STABILITY RICHARD P. CRONIN TIMOTHY HAMLIN AUTHORS ii │ Copyright©2010 The Henry L. Stimson Center Cover design by Shawn Woodley All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 Phone: 202.223.5956 fax: 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org | iii CONTENTS Preface............................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ............................................................................................ v Hydropower Proposals in the Lower Mekong Basin.......................................viii Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 The Political Economy of Hydropower.............................................................. 5 Man Versus Nature in the Mekong Basin: A Recurring Story..................... 5 D rivers of Hydropower Development................................................................ 8 Dams and Civil Society in Thailand.......................................................... 10 From Migratory to Reservoir Fisheries .................................................... 13 Elusive Support for Cooperative Water Management..................................... -

Water Situation in China – Crisis Or Business As Usual?

Water Situation In China – Crisis Or Business As Usual? Elaine Leong Master Thesis LIU-IEI-TEK-A--13/01600—SE Department of Management and Engineering Sub-department 1 Water Situation In China – Crisis Or Business As Usual? Elaine Leong Supervisor at LiU: Niclas Svensson Examiner at LiU: Niclas Svensson Supervisor at Shell Global Solutions: Gert-Jan Kramer Master Thesis LIU-IEI-TEK-A--13/01600—SE Department of Management and Engineering Sub-department 2 This page is left blank with purpose 3 Summary Several studies indicates China is experiencing a water crisis, were several regions are suffering of severe water scarcity and rivers are heavily polluted. On the other hand, water is used inefficiently and wastefully: water use efficiency in the agriculture sector is only 40% and within industry, only 40% of the industrial wastewater is recycled. However, based on statistical data, China’s total water resources is ranked sixth in the world, based on its water resources and yet, Yellow River and Hai River dries up in its estuary every year. In some regions, the water situation is exacerbated by the fact that rivers’ water is heavily polluted with a large amount of untreated wastewater, discharged into the rivers and deteriorating the water quality. Several regions’ groundwater is overexploited due to human activities demand, which is not met by local. Some provinces have over withdrawn groundwater, which has caused ground subsidence and increased soil salinity. So what is the situation in China? Is there a water crisis, and if so, what are the causes? This report is a review of several global water scarcity assessment methods and summarizes the findings of the results of China’s water resources to get a better understanding about the water situation. -

Ganges River Mekong River Himalayan Mountains Huang He (Yellow) River Yangtze River Taklimakan Desert Indus River Gobi Desert B

Southern & Eastern Asia Physical Features and Countries Matching Activity Cut out each card. Match the name to the image and description. Ganges Mekong Himalayan River River Mountains Huang He Yangtze Taklimakan (Yellow) River Desert River Indus Gobi Bay of River Desert Bengal Yellow Indian Sea of Sea Ocean Japan Korean South China India Peninsula Sea China Indonesia Vietnam North South Japan Korea Korea Southern & Eastern Asia Physical Features and Countries Matching Activity Southern & Eastern Asia Physical Features and Countries Matching Activity Southern & Eastern Asia Physical Features and Countries Matching Activity Asia’s largest desert that stretches across southern Mongolia and northern China Largest and longest river in China’s second largest river China; very important that causes devastating because it provides floods. It is named for the hydroelectric power, water for muddy yellow silt it carries. irrigation, and transportation for cargo ships. Flows through China, Starts in the Himalayan Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Mountains; most important river in Laos, Cambodia, and India because it runs through the Vietnam. One of the region’s most fertile and highly populated most important crops, rice, is areas; considered sacred by the grown in the river basin. Hindu religion. World’s highest mountain range that sits along the Located in northwestern northern edge of India; China between two mountain includes Mount Everest, the ranges highest mountain in the world. Begins high in the Himalayas and slowly runs through India Third largest -

Dams and Development in China

BRYAN TILT DAMS AND The Moral Economy DEVELOPMENT of Water and Power IN CHINA DAMS AND DEVELOPMENT CHINA IN CONTEMPORARY ASIA IN THE WORLD CONTEMPORARY ASIA IN THE WORLD DAVID C. KANG AND VICTOR D. CHA, EDITORS This series aims to address a gap in the public-policy and scholarly discussion of Asia. It seeks to promote books and studies that are on the cutting edge of their respective disciplines or in the promotion of multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary research but that are also accessible to a wider readership. The editors seek to showcase the best scholarly and public-policy arguments on Asia from any field, including politics, his- tory, economics, and cultural studies. Beyond the Final Score: The Politics of Sport in Asia, Victor D. Cha, 2008 The Power of the Internet in China: Citizen Activism Online, Guobin Yang, 2009 China and India: Prospects for Peace, Jonathan Holslag, 2010 India, Pakistan, and the Bomb: Debating Nuclear Stability in South Asia, Šumit Ganguly and S. Paul Kapur, 2010 Living with the Dragon: How the American Public Views the Rise of China, Benjamin I. Page and Tao Xie, 2010 East Asia Before the West: Five Centuries of Trade and Tribute, David C. Kang, 2010 Harmony and War: Confucian Culture and Chinese Power Politics, Yuan-Kang Wang, 2011 Strong Society, Smart State: The Rise of Public Opinion in China’s Japan Policy, James Reilly, 2012 Asia’s Space Race: National Motivations, Regional Rivalries, and International Risks, James Clay Moltz, 2012 Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations, Zheng Wang, 2012 Green Innovation in China: China’s Wind Power Industry and the Global Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy, Joanna I. -

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Estuaries of Two Rivers of the Sea of Japan

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Estuaries of Two Rivers of the Sea of Japan Tatiana Chizhova 1,*, Yuliya Koudryashova 1, Natalia Prokuda 2, Pavel Tishchenko 1 and Kazuichi Hayakawa 3 1 V.I.Il’ichev Pacific Oceanological Institute FEB RAS, 43 Baltiyskaya Str., Vladivostok 690041, Russia; [email protected] (Y.K.); [email protected] (P.T.) 2 Institute of Chemistry FEB RAS, 159 Prospect 100-let Vladivostoku, Vladivostok 690022, Russia; [email protected] 3 Institute of Nature and Environmental Technology, Kanazawa University, Kakuma, Kanazawa 920-1192, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-914-332-40-50 Received: 11 June 2020; Accepted: 16 August 2020; Published: 19 August 2020 Abstract: The seasonal polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) variability was studied in the estuaries of the Partizanskaya River and the Tumen River, the largest transboundary river of the Sea of Japan. The PAH levels were generally low over the year; however, the PAH concentrations increased according to one of two seasonal trends, which were either an increase in PAHs during the cold period, influenced by heating, or a PAH enrichment during the wet period due to higher run-off inputs. The major PAH source was the combustion of fossil fuels and biomass, but a minor input of petrogenic PAHs in some seasons was observed. Higher PAH concentrations were observed in fresh and brackish water compared to the saline waters in the Tumen River estuary, while the PAH concentrations in both types of water were similar in the Partizanskaya River estuary, suggesting different pathways of PAH input into the estuaries. -

Downstream Impacts of Lancang Dams in Hydrology, Fisheries And

Downstream Impacts of Lancang/ Upper Mekong Dams: An Overview Pianporn Deetes International Rivers August 2014 • In the wet season, the Lancang dams run at normal operation levels for power generation and release extra water if the water level exceeds normal water level. • In the dry season, Xiaowan and Nuozhadu will generally release the water to downstream dams so that to ensure other dams can run at full capacity. • The total storage of six complete dams is 41 km3. And the total regulation storage is 22 km3 Dam Name Installed Dam Height Total Regulation Regulation Status Capacity (m) Storage storage Type (MW) (km3) (km3) Gongguoqiao 900 130 0.32 0.05 Seasonal Completed (2012) Xiaowan 4200 292 15 10 Yearly Completed (2010) Manwan 1550 126 0.92 0.26 Seasonal Completed (phase 1 in1995 and phase 2 in 2007) Dachaoshan 1350 118 0.94 0.36 Seasonal Completed (2003) Nuozhadu 5850 261.5 22.7 11.3 Yearly Completed (2012) Jinghong 1750 118 1.14 0.23 Seasonal Completed (2009) Ganlanba 155 60.5 Run-of- Planned river Hydrology Flow Lancang dams has increased dry season flows and reduces wet season flows: • At China border, the flow can increase as much as 100% in March due to the operation of Manwan, Daochaoshan Jinghong and Xiaowan dams (Chen and He, 2000) • On average, the Lower Lancang cascade increased the December–May discharge by 34 to155 % and decreased the discharge from July to September by 29–36 % at Chiang Saen station (Rasanen, 2012) • After the Manwan Dam was built, the average minimum flow yearly decreased around 25% at Chiang Saen (Zhong, 2007) Rasanen (2012) Hydrology Water Level Monthly average water level data from Chiang Khong clearly showed the impacts of the first filling of Nuozhadu Dam. -

Channel Adjustments in Response to the Operation of Large Dams: the Upper Reach of the Lower Yellow River

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 1-1-2012 Channel adjustments in response to the operation of large dams: the upper reach of the lower Yellow River Yuanxu Ma Chinese Academy of Sciences He Qing Huang Chinese Academy of Sciences Gerald C. Nanson University of Wollongong, [email protected] Yongi Li Yellow River Institute of Hydraulic Research China Wenyi Yao Yellow River Institute of Hydraulic Research, China Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/scipapers Part of the Life Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Ma, Yuanxu; Huang, He Qing; Nanson, Gerald C.; Li, Yongi; and Yao, Wenyi: Channel adjustments in response to the operation of large dams: the upper reach of the lower Yellow River 2012, 35-48. https://ro.uow.edu.au/scipapers/4279 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Channel adjustments in response to the operation of large dams: the upper reach of the lower Yellow River Abstract The Yellow River in China carries an extremely large sediment load. River channel-form and lateral shifting in a dynamic, partly meandering and partly braided reach of the lower Yellow River, have been significantly influenced by construction of Sanmenxia Dam in 1960, Liujiaxia Dam in 1968, Longyangxia Dam in 1985 and Xiaolangdi Dam in 1997. Using observations from Huayuankou Station, 128 km downstream of Xiaolangdi Dam, this study examines changes in the river before and after construction of the dams. -

Environmental and Social Impacts of Lancang Dams

Xiaowan Dam Environmental and Social Impacts of Lancang Dams the water to downstream dams so as to ensure other dams can run at full capacity. Xiaowan and Nuozhadu are the two yearly regulated dams with big regulation storages, while all the others have very limited seasonal regulation capacity. A wide range of studies have confirmed that the wet season Summary flow will decrease, while the dry season flow will increase because of the operation of the Lancang dams. Because the This research brief focuses on the downstream impacts on Lancang river contributes 45% of water to the Mekong basin hydrology, fisheries and sedimentations caused by the Lower in the dry season, the flow change impacts on downstream Lancang cascade in China. Manwan and Dachaoshan were reaches will be more obvious increasing flows by over 100% the first two dams completed on the Lancang River (in 1995 at Chiang Saen. An increase in water levels in the dry sea- (first phase) and 2003 respectively) and many changes have son will reduce the exposed riverbank areas for river bank been observed. Many scientific studies have been done to gardens and other seasonal agriculture. Millions of villagers evaluate the impacts from Manwan and Dachaoshan dams who live along the Mekong River grow vegetables in river- by analyzing monitoring and survey data. With the two big- bank gardens and their livelihoods will be largely impacted gest dams of the cascade, Xiaowan and Nuozhadu, put into if losing the gardens. In the wet season, the decrease of operation in 2010 and 2012, bigger downstream impacts are flow at Chiang Saen caused by the Lancang dams holding expected to be observed. -

Water Resource Competition in the Brahmaputra River Basin: China, India, and Bangladesh Nilanthi Samaranayake, Satu Limaye, and Joel Wuthnow

Water Resource Competition in the Brahmaputra River Basin: China, India, and Bangladesh Nilanthi Samaranayake, Satu Limaye, and Joel Wuthnow May 2016 Distribution unlimited This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: 14-106755-000-INP. For questions or comments about this study, contact Nilanthi Samaranayake at [email protected] Cover Photography: Brahmaputra River, India: people crossing the Brahmaputra River at six in the morning. Credit: Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest, "Brahmaputra River, India," Maria Stenzel / National Geographic Society / Universal Images Group Rights Managed / For Education Use Only, http://quest.eb.com/search/137_3139899/1/137_3139899/cite. Approved by: May 2016 Ken E Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2016 CNA Abstract The Brahmaputra River originates in China and runs through India and Bangladesh. China and India have fought a war over contested territory through which the river flows, and Bangladesh faces human security pressures in this basin that will be magnified by upstream river practices. Controversial dam-building activities and water diversion plans could threaten regional stability; yet, no bilateral or multilateral water management accord exists in the Brahmaputra basin. This project, sponsored by the MacArthur Foundation, provides greater understanding of the equities and drivers fueling water insecurity in the Brahmaputra River basin. After conducting research in Dhaka, New Delhi, and Beijing, CNA offers recommendations for key stakeholders to consider at the subnational, bilateral, and multilateral levels to increase cooperation in the basin. These findings lay the foundation for policymakers in China, India, and Bangladesh to discuss steps that help manage and resolve Brahmaputra resource competition, thereby strengthening regional security. -

CONTROLLING the YELLOW RIVER 2000 Years of Debate On

Technical Secretariat for the International Sediment Initiative IHP, UNESCO January 2019 Published by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France, © 2019 by UNESCO This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/ terms-useccbysa-en). The present license applies exclusively to the text content of the publication. For the use of any material not clearly identified as belonging to UNESCO, prior permission shall be requested. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNESCO. ©UNESCO 2019 DESIGN, LAYOUT & ILLUSTRATIONS: Ana Cuna ABSTRACT Throughout the history of China, the Yellow was the major strategy of flood control. Two River has been associated with frequent flood extremely different strategies were proposed and disasters and changes in the course of its lower practiced in the past 2000 years, i.e. the wide river reaches. The river carries sediment produced and depositing sediment strategy and the narrow by soil erosion from the Loess Plateau and the river and scouring sediment strategy. Wang Jing Qinghai-Tibet plateau and deposits the sediment implemented a large-scale river training project on the channel bed and in the estuary. -

World Bank Document

Documentof The World Bank FOROFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No.: 18127 IMPLEMENTATIONCOMPLETION REPORT 'CHINA Public Disclosure Authorized SHAANXIAGRICULTURLAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT CREDIT1997-CN June 29, 1998 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Rural Development and Natural Resources Unit East Asia and Pacific Regional Office This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the perfonnance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit = Yuan (Y) 1989 $1=Y 3.76 1990 $1=Y 4.78 1991 $1=Y 5.32 1992 $1=Y 5.42 1993 $1=Y 5.73 1994 $1=Y 8.50 1995 $1=Y 8.30 1996 $1=Y 8.30 1997 $1=Y 8.30 FISCAL YEAR January 1-December 31 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES Metric System 2 mu = 666.7 square meters (m ) 15 mu = 1 hectare (ha) ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS EASRD - Rural Development and Natural Resources Sector Unit of the East Asia and Pacific Regional Office EIRR - Economic internal rate of return FIRR - Financial internal rate of return FY - Fiscal year GPS - Grandparent Stock IBRD - International Bank for Reconstruction and Development ICB - International Competitive Bidding ICR - Implementation Completion Report IDA - International Development Association ITC - International Tendering Company of China National Technology Import & Export Corporation NCB - National Competitive Bidding O&M - Operations and maintenance OD - Operational Directive (of the World Bank) PMO - Project Management Office PPC - Provincial Planning Commission SAR - Staff Appraisal Report SDR - Special Drawing Rights Vice President :Jean-Michel Severino, EAPVP Country Director :Yukon Huang, EACCF Sector Manager :Geoffrey Fox, EASRD Staff Member :Daniel Gunaratnam, Principal Water Resources Specialist, EACCF FOR OFFICIALUSE ONLY CONTENTS PREFACE ....................................................... -

View Sample Support Material

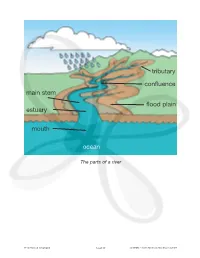

tributary confluence main stem flood plain estuary mouth ocean The parts of a river 9–12 Physical Geography 23 of 77 © NAMC - North American Montessori Center Summary sheet: Main drainage patterns of rivers Type of Drainage Pattern Appearance Description dendritic resembles the branches of a occurs where the land is made tree or the veins on a leaf of the same type of rock, so that the water flows with the same amount of resistance from all areas, producing a predictable pattern of drainage radial streams radiate outward from caused by water running down a peak in all directions from a high point such as a mountain trellis streams flow in roughly the forms where fractured rock same direction, like a trellis creates parallel grooves that the river naturally follows rectangular streams flow as if following a occurs where hard rock fractures rectangular grid in a grid pattern, and the water follows the rock pattern centripetal streams flow toward a occurs where a depression in the central point land collects water in a central location, often forming a lake 9–12 Physical Geography 24 of 77 © NAMC - North American Montessori Center dendritic radial drainage drainage pattern pattern trellis rectangular drainage drainage pattern pattern centripetal drainage pattern Drainage patterns 9–12 Physical Geography 25 of 77 © NAMC - North American Montessori Center Major rivers of the world Name Length Location Source Mouth Nile 4,160 mi (6,695 km) Africa Uganda, Kenya Egypt Amazon 4,000 mi (6,400 km) South America Peru Brazil Yangtze 3,900 mi (6,300