Maintenance Activities of the American Redstart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Redstarts

San Antonio Audubon Society May/June 2021 Newsletter American Redstarts By Mike Scully At the time of this writing (early April), the glorious annual spring migration of songbirds through our area is picking up. Every spring I keep a special eye out for one of my favorite migrants, the American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla). These beautiful warblers flutter actively through the foliage, tail spread, wings drooped, older males clad in black and orange, females and second year males in shades of gray, olive green and yellow. For years, the American Redstart was the only species remaining in the genus Setophaga, until a comprehensive genetic analysis of the Family Parulidae resulted in this genus being grouped with more than 32 species formerly placed in the genus Dendroica and Wilsonia. The name Setophaga was applied to the whole by virtue of seniority. Though now grouped in a large genus, the American Redstart remains an outlier, possessing proportionately large wings, a long tail, and prominent rictal bristles at the base of the relatively wide flat beak, all adaptations to a flycatching mode of foraging. Relatively heavy thigh musculature and long central front toes are apparently adaptations to springing into the air after flying insects. The foraging strategy of redstarts differs from that of typical flycatchers. Redstarts employ a more warbler-like maneuver, actively moving through the foliage, making typically short sallies after flying insect prey, and opportunistically gleaning insects from twigs and leaves while hovering or perched. The wings are frequently drooped and the colorful tail spread wide in order to flush insect prey. -

Uropygial Gland in Birds

UROPYGIAL GLAND IN BIRDS Prepared by Dr. Subhadeep Sarker Associate Professor, Department of Zoology, Serampore College Occurrence and Location: • The uropygial gland, often referred to as the oil or preen gland, is a bilobed gland and is found at the dorsal base of the tail of most psittacine birds. • The uropygial gland is a median dorsal gland, one per bird, in the synsacro-caudal region. A half moon-shaped row of feather follicles of the upper median and major tail coverts externally outline its position. • The uropygial area is located dorsally over the pygostyle on the midline at the base of the tail. • This gland is most developed in waterfowl but very reduced or even absent in many parrots (e.g. Amazon parrots), ostriches and many pigeons and doves. Anatomy: • The uropygial gland is an epidermal bilobed holocrine gland localized on the uropygium of most birds. • It is composed of two lobes separated by an interlobular septum and covered by an external capsule. • Uropygial secretory tissue is housed within the lobes of the gland (Lobus glandulae uropygialis), which are nearly always two in number. Exceptions occur in Hoopoe (Upupa epops) with three lobes, and owls with one. Duct and cavity systems are also contained within the lobes. • The architectural patterns formed by the secretory tubules, the cavities and ducts, differ markedly among species. The primary cavity can comprise over 90% of lobe volume in the Oilbird (Steatornis caripensis) and some woodpeckers and pigeons. • The gland is covered by a circlet or tuft of down feathers called the uropygial wick in many birds. -

American Redstart Setophaga Ruticilla

American Redstart Setophaga ruticilla Folk Name: Butterfly Bird, Candelita (Spanish) Status: Migrant and local Breeder Abundance: Common in migration Habitat: Bottomland hardwoods, wide creek floodplains, moist deciduous forest slopes The American Redstart is a spectacular black-and-red- colored bird that is one of our most common migrants and one of the easiest of our warblers to identify. It migrates through this region in good numbers each spring and fall and some stop to breed at scattered locations across both states. The Charlotte News published this description, written by an avid North Carolina birder, on October 11, 1910: Another “find” in which the bird lover takes much pleasure is in the locating of that marvelously colored member of the great Wood Warbler family, the American Redstart. …The great passing flocks of migratory warblers drop the Redstart off each spring on their Northern journey, and pick him up each fall. A full mature male Redstart, which by the way, acquires his plumage only after two years in shrubs or the branches of trees. It’s easy to observe this growth, is truly an exquisite specimen of nature’s behavior while out birding during migration. handiwork. Imagine a wee small bird, smaller than Leverett Loomis reported the redstart as “abundant” a canary, of shining black on breast, throat and back, during spring and fall migration in Chester County while on it wings and tail and sides are patches of during the late 1870s, and one year he collected three bright salmon color. These strangely colored birds males on 17 August. William McIlwaine provided the are called in Cuba “Candelita,” the little torch that first records of the American Redstart in Mecklenburg flames in the gloomy depths of tropical forests. -

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brandan L. Gray August 2019 © 2019 Brandan L. Gray. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers by BRANDAN L. GRAY has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Professor of Biological Sciences Florenz Plassmann Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT GRAY, BRANDAN L., Ph.D., August 2019, Biological Sciences Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In a rapidly changing world, species are faced with habitat alteration, changing climate and weather patterns, changing community interactions, novel resources, novel dangers, and a host of other natural and anthropogenic challenges. Conservationists endeavor to understand how changing ecology will impact local populations and local communities so efforts and funds can be allocated to those taxa/ecosystems exhibiting the greatest need. Ecological morphological and functional morphological research form the foundation of our understanding of selection-driven morphological evolution. Studies which identify and describe ecomorphological or functional morphological relationships will improve our fundamental understanding of how taxa respond to ecological selective pressures and will improve our ability to identify and conserve those aspects of nature unable to cope with rapid change. The New World wood warblers (family Parulidae) exhibit extensive taxonomic, behavioral, ecological, and morphological variation. -

Wood Warblers Wildlife Note

hooded warbler 47. Wood Warblers Like jewels strewn through the woods, Pennsylvania’s native warblers appear in early spring, the males arrayed in gleaming colors. Twenty-seven warbler species breed commonly in Pennsylvania, another four are rare breeders, and seven migrate through Penn’s Woods headed for breeding grounds farther north. In central Pennsylvania, the first species begin arriving in late March and early April. Louisiana waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla) and black and white warbler (Mniotilta varia) are among the earliest. The great mass of warblers passes through around mid-May, and then the migration trickles off until it ends in late May by which time the trees have leafed out, making it tough to spot canopy-dwelling species. In southern Pennsylvania, look for the migration to begin and end a few days to a week earlier; in northern Pennsylvania, it is somewhat later. As summer progresses and males stop singing on territory, warblers appear less often, making the onset of fall migration difficult to detect. Some species begin moving south as early as mid and late July. In August the majority specific habitat types and show a preference for specific of warblers start moving south again, with migration characteristics within a breeding habitat. They forage from peaking in September and ending in October, although ground level to the treetops and eat mainly small insects stragglers may still come through into November. But by and insect larvae plus a few fruits; some warblers take now most species have molted into cryptic shades of olive flower nectar. When several species inhabit the same area, and brown: the “confusing fall warblers” of field guides. -

Delayed Plumage Maturation and the Presumed Prealternate Molt in American Redstarts

WilsonBull., 95(2), 1983, pp. 199-208 DELAYED PLUMAGE MATURATION AND THE PRESUMED PREALTERNATE MOLT IN AMERICAN REDSTARTS SIEVERT ROHWER, WILLIAM P. KLEIN, JR., AND SCOTT HEARD The American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla) is one of about 30 sexually dichromatic North American passerine species in which males exhibit a delayed plumage maturation (Rohwer et al. 1980). Males in their first win- ter and in their first potential breeding season are largely like females in coloration. These young males have only a few scattered black feathers on their head, hack, and breast, areas where adult males are solid black, and they have yellow rather than the orange patches characteristic of adult males in their wings and tail. Two of four hypotheses reviewed by Rohwer et al. (1980) are relevant to the delay in plumage maturation characteristic of these 30 dichromatic passerine species. Both describe hypothesized best-alternative responses by which young males have minimized their disadvantage in one or both forms of sexual competition. The first, which we here rename, is the Cryptic Hypothesis (CH). Selander (1965) devel- oped this hypothesis by arguing that the costs of a conspicuous breeding plumage would not he repaid in yearling males because of their very lim- ited breeding opportunities. This was called the sexual selection hypoth- esis by Rohwer et al. (1980) and the delayed maturation hypothesis by Procter-Gray and Holmes (1981). The second is the Female Mimicry Hy- pothesis (FMH). Rohwer and his coworkers (Rohwer et al. 1980, Rohwer 1983) developed this hypothesis by arguing that young males increase their chances of obtaining female-worthy territories and breeding as yearlings by mimicking females and, thus, eliciting less aggression from adult males in the early stages of territory establishment. -

American Redstarts

American Redstarts By Mike Scully At the time of this writing (early April), the glorious annual spring migration of songbirds through our area is picking up. Every spring I keep a special eye out for one of my favorite migrants, the American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla). These beautiful warblers flutter actively through the foliage, tail spread, wings drooped, older males clad in black and orange, females and second year males in shades of gray, olive green and yellow. For years, the American Redstart was the only species remaining in the genus Setophaga, until a comprehensive genetic analysis of the Family Parulidae resulted in this genus being grouped with more than 32 species formerly placed in the genus Dendroica and Wilsonia. The name Setophaga was applied to the whole by virtue of seniority. Though now grouped in a large genus, the American Redstart remains an outlier, possessing proportionately large wings, a long tail, and prominent rictal bristles at the base of the relatively wide flat beak, all adaptations to a flycatching mode of foraging. Relatively heavy thigh musculature and long central front toes are apparently adaptations to springing into the air after flying insects. American Redstart by Dan Pancamo The foraging strategy of redstarts differs from that of typical flycatchers. Redstarts employ a more warbler-like maneuver, actively moving through the foliage, making typically short sallies after flying insect prey, and opportunistically gleaning insects from twigs and leaves while hovering or perched. The wings are frequently drooped and the colorful tail spread wide in order to flush insect prey. Among birds in general it is common for sometimes minor differences in coloration to exist, depending on the age of the bird, with full adult plumage not achieved until one or more years of age. -

Sex Recognition by Odour and Variation in the Uropygial Gland Secretion In

1 Sex recognition by odour and variation in the uropygial gland secretion in 2 starlings 3 4 Luisa Amo1, Jesús Miguel Avilés1, Deseada Parejo1, Aránzazu Peña2, Juan Rodríguez1, 5 Gustavo Tomás1 6 7 1 Departamento de Ecología Funcional y Evolutiva, Estación Experimental de Zonas 8 Áridas (CSIC), Carretera de Sacramento s/n, E-04120, La Cañada de San Urbano, 9 Almería, Spain. 10 2 Instituto Andaluz de Ciencias de la Tierra (IACT, CSIC-UGR), Avda de las Palmeras, 11 4, 18100, Armilla, Granada, Spain. 12 13 *corresponding author: Luisa Amo. Departamento de Ecología Funcional y Evolutiva, 14 Estación Experimental de Zonas Áridas (CSIC), Carretera de Sacramento s/n, E-04120, 15 La Cañada de San Urbano, Almería, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 16 17 18 Running headline: Odour-based sex recognition in a bird 19 20 2 21 1. Although a growing body of evidence supports that olfaction based on chemical 22 compounds emitted by birds may play a role in individual recognition, the possible role 23 of chemical cues in sexual selection of birds has been only preliminarily studied. 24 2. We investigated for the first time whether a passerine bird, the spotless starling 25 Sturnus unicolor, was able to discriminate the sex of conspecifics by using olfactory 26 cues and whether the size and secretion composition of the uropygial gland convey 27 information on sex, age and reproductive status in this species. 28 3. We performed a blind choice experiment during mating and we found that starlings 29 were able to discriminate the sex of conspecifics by using chemical cues alone. -

Taxonomic Relationships Among the American Redstarts

TAXONOMIC RELATIONSHIPS AMONG THE AMERICAN REDSTARTS KENNETH C. PARKES N recent years certain bird taxonomists have indulged in what might be I described as a veritable orgy of genus-lumping. Small genera, particularly monotypic genera, must, it seems, be somehow combined with one another, or shoehorned into larger genera (see, for example, the footnote on Uropsila, Paynter, 1960:430). To some extent this is a healthy trend, as many bird families are undeniably oversplit. Much of the recent lumping, however, has a fundamental shortcoming; the authors make little or no effort to re-evaluate the composition of the currently accepted genera before simply emptying the contents of two bureau drawers into one. It is possible, indeed probable, that some of our genera as they now stand are composite and artificial, not reflecting actual relationships. The answer to such problems is not simple lumping, but rather redefinition of genera, with the generic lines drawn in different places. An excellent example is provided by the case history of the North American forest thrushes. Ridgway (1907:19, 35) pointed out many years ago the close relationship between the thrushes generally placed in the two genera Hylocichlu and Cutharus. Ripley (1952), in a paper which advocated merging a number of genera of thrushes, formally proposed the lumping of Hylocichlu and Cutharus under the latter name, but without any analytical study of the species currently placed in these two genera. This proposition had already been made in several unpublished theses dealing with regional avifaunas (Loetscher, 1941:664; Phillips, 1946:309; Parkes, 1952:384), also as a straight lumping of the two genera. -

MORPHOLOGICAL and ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION in OLD and NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the College O

MORPHOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IN OLD AND NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Clay E. Corbin August 2002 This dissertation entitled MORPHOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IN OLD AND NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS BY CLAY E. CORBIN has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Associate Professor, Department of Biological Sciences Leslie A. Flemming Dean, College of Arts and Sciences CORBIN, C. E. Ph.D. August 2002. Biological Sciences. Morphological and Ecological Evolution in Old and New World Flycatchers (215pp.) Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In both the Old and New Worlds, independent clades of sit-and-wait insectivorous birds have evolved. These independent radiations provide an excellent opportunity to test for convergent relationships between morphology and ecology at different ecological and phylogenetic levels. First, I test whether there is a significant adaptive relationship between ecology and morphology in North American and Southern African flycatcher communities. Second, using morphological traits and observations on foraging behavior, I test whether ecomorphological relationships are dependent upon locality. Third, using multivariate discrimination and cluster analysis on a morphological data set of five flycatcher clades, I address whether there is broad scale ecomorphological convergence among flycatcher clades and if morphology predicts a course measure of habitat preference. Finally, I test whether there is a common morphological axis of diversification and whether relative age of origin corresponds to the morphological variation exhibited by elaenia and tody-tyrant lineages. -

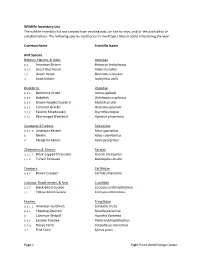

Master Wildlife Inventory List

Wildlife Inventory List The wildlife inventory list was created from existing data, on site surveys, and/or the availability of suitable habitat. The following species could occur in the Project Area at some time during the year: Common Name Scientific Name Bird Species Bitterns, Herons, & Allies Ardeidae D, E American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus A, E, F Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias E, F Green Heron Butorides virescens D Least bittern Ixobrychus exilis Blackbirds Icteridae B, E, F Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula B, E, F Bobolink Dolichonyx oryzivorus B, E, F Brown-headed Cowbird Molothrus ater B, E, F Common Grackle Quiscalus quiscula B, E, F Eastern Meadowlark Sturnella magna B, E, F Red-winged Blackbird Agelaius phoeniceus Caracaras & Falcons Falconidae B, E, F, G American Kestrel Falco sparverius B Merlin Falco columbarius D Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus Chickadees & Titmice Paridae B, E, F, G Black-capped Chickadee Poecile atricapillus E, F, G Tufted Titmouse Baeolophus bicolor Creepers Certhiidae B, E, F Brown Creeper Certhia americana Cuckoos, Roadrunners, & Anis Cuculidae D, E, F Black-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus erythropthalmus E, F Yellow-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus americanus Finches Fringillidae B, E, F, G American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis B, E, F Chipping Sparrow Spizella passerina G Common Redpoll Acanthis flammea B, E, F Eastern Towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus E, F, G House Finch Carpodacus mexicanus B, E Pine Siskin Spinus pinus Page 1 Eight Point Wind Energy Center E, F, G Purple Finch Carpodacus purpureus B, E Red Crossbill -

Godavari Birds Godavari Birds

Godavari Birds Godavari Birds i Godavari Birds From Godavari to Phulchowki peak, there are an estimated 270 bird species with 17 listed as endangered. Godavari proper has 100 species recorded. It is impossible to photograph all of them. A reference list is provided at the end of the booklet so that you can continue to locate birds that we have not been able to photograph. This fun booklet presents a few of the more common and eye catching birds that hopefully will catch your eye too. Bird watching provides valuable information. Consistent records give indications of habitat loss, changes in climate, migration patterns and new or missing previous records. Years of data have been collected across Nepal to give a picture of birds in place and time. The oldest Nepal record is from 1793 when it was more common to catch and skin birds for museum collections. Compiled by Karen Conniff, Ron Hess and Erling Valdemar Holmgren ii Godavari Birds Godavari Birds This basic guide is organized by family and sub-family groupings. The purpose is to make it easier to identify the birds sighted at the ICIMOD Knowledge Park and surrounding areas in Godavari. There are several bird watching tours and groups of regular bird watchers to join with and improve your knowledge of local birds. If you have comments, want to add a new identification record or found errors in this booklet please contact: Karen Conniff – [email protected] iii Godavari Birds Blue-throated Barbet (Ron Hess) iv Godavari Birds Family RHess Phasianidae or Kalij Pheasant (female) Partridges