Taxonomic Relationships Among the American Redstarts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Parula Setophaga Americana

Northern Parula Setophaga americana Folk Name: Blue Yellow-backed Warbler Status: Breeder Abundance: Uncommon to Fairly Common Habitat: Bottomland forests—damp, low woods “Cute.” That seems to be the most common adjective ascribed to this petite, energetic warbler. Although, “adorable” is certainly in the running as well. It is a colorful bird with a mix of blue gray, yellow green, bright yellow, and bold white, with the addition of a dab of reddish and black on the males. It is our smallest member of the warbler family, about the size of the tiny Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, but this bird has a very short tail. As such, it can be hard to see amongst the foliage while it is foraging for insects and spiders in the top of a tree. Fortunately, the male is quite a loud and persistent singer and a patient observer, following the bird’s song, may soon be rewarded with a view of it. The song of the Northern Parula has been variously R. B. McLaughlin found a Northern Parula nest with described as a wind-up zee-zee-zee trill with an abrupt, eggs in Iredell County on May 11, 1887. In December of punctuated, downward zip note at the end, or as a “quaint that year, he published a brief article describing another drowsy, little gurgling sizzle, chip-er, chip-er, chip-er, nest of the Northern Parula which he had found in chee-ee-ee-ee.” It breeds in much of the eastern United Statesville several years earlier. He first noticed a clump of States and throughout both Carolinas. -

American Redstarts

San Antonio Audubon Society May/June 2021 Newsletter American Redstarts By Mike Scully At the time of this writing (early April), the glorious annual spring migration of songbirds through our area is picking up. Every spring I keep a special eye out for one of my favorite migrants, the American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla). These beautiful warblers flutter actively through the foliage, tail spread, wings drooped, older males clad in black and orange, females and second year males in shades of gray, olive green and yellow. For years, the American Redstart was the only species remaining in the genus Setophaga, until a comprehensive genetic analysis of the Family Parulidae resulted in this genus being grouped with more than 32 species formerly placed in the genus Dendroica and Wilsonia. The name Setophaga was applied to the whole by virtue of seniority. Though now grouped in a large genus, the American Redstart remains an outlier, possessing proportionately large wings, a long tail, and prominent rictal bristles at the base of the relatively wide flat beak, all adaptations to a flycatching mode of foraging. Relatively heavy thigh musculature and long central front toes are apparently adaptations to springing into the air after flying insects. The foraging strategy of redstarts differs from that of typical flycatchers. Redstarts employ a more warbler-like maneuver, actively moving through the foliage, making typically short sallies after flying insect prey, and opportunistically gleaning insects from twigs and leaves while hovering or perched. The wings are frequently drooped and the colorful tail spread wide in order to flush insect prey. -

American Redstart Setophaga Ruticilla

American Redstart Setophaga ruticilla Folk Name: Butterfly Bird, Candelita (Spanish) Status: Migrant and local Breeder Abundance: Common in migration Habitat: Bottomland hardwoods, wide creek floodplains, moist deciduous forest slopes The American Redstart is a spectacular black-and-red- colored bird that is one of our most common migrants and one of the easiest of our warblers to identify. It migrates through this region in good numbers each spring and fall and some stop to breed at scattered locations across both states. The Charlotte News published this description, written by an avid North Carolina birder, on October 11, 1910: Another “find” in which the bird lover takes much pleasure is in the locating of that marvelously colored member of the great Wood Warbler family, the American Redstart. …The great passing flocks of migratory warblers drop the Redstart off each spring on their Northern journey, and pick him up each fall. A full mature male Redstart, which by the way, acquires his plumage only after two years in shrubs or the branches of trees. It’s easy to observe this growth, is truly an exquisite specimen of nature’s behavior while out birding during migration. handiwork. Imagine a wee small bird, smaller than Leverett Loomis reported the redstart as “abundant” a canary, of shining black on breast, throat and back, during spring and fall migration in Chester County while on it wings and tail and sides are patches of during the late 1870s, and one year he collected three bright salmon color. These strangely colored birds males on 17 August. William McIlwaine provided the are called in Cuba “Candelita,” the little torch that first records of the American Redstart in Mecklenburg flames in the gloomy depths of tropical forests. -

Genomic Variation Across the Yellow-Rumped Warbler Species Complex

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2016 Genomic variation across the Yellow-rumped Warbler species complex Toews, David P L ; Brelsford, Alan ; Grossen, Christine ; Milá, Borja ; Irwin, Darren E Abstract: Populations that have experienced long periods of geographic isolation will diverge over time. The application of highthroughput sequencing technologies to study the genomes of related taxa now allows us to quantify, at a fine scale, the consequences of this divergence across the genome. Throughout a number of studies, a notable pattern has emerged. In many cases, estimates of differentiation across the genome are strongly heterogeneous; however, the evolutionary processes driving this striking pattern are still unclear. Here we quantified genomic variation across several groups within the Yellow-rumped Warbler species complex (Setophaga spp.), a group of North and Central American wood warblers. We showed that genomic variation is highly heterogeneous between some taxa and that these regions of high differentiation are relatively small compared to those in other study systems. We found that theclusters of highly differentiated markers between taxa occur in gene-rich regions of the genome and exhibitlow within-population diversity. We suggest these patterns are consistent with selection, shaping genomic divergence in similar genomic regions across the different populations. Our study also confirms previous results relying on fewergenetic markers that several of the phenotypically distinct groups in the system are also genomically highly differentiated, likely to the point of full species status. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1642/AUK-16-61.1 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-127199 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Toews, David P L; Brelsford, Alan; Grossen, Christine; Milá, Borja; Irwin, Darren E (2016). -

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brandan L. Gray August 2019 © 2019 Brandan L. Gray. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers by BRANDAN L. GRAY has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Professor of Biological Sciences Florenz Plassmann Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT GRAY, BRANDAN L., Ph.D., August 2019, Biological Sciences Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In a rapidly changing world, species are faced with habitat alteration, changing climate and weather patterns, changing community interactions, novel resources, novel dangers, and a host of other natural and anthropogenic challenges. Conservationists endeavor to understand how changing ecology will impact local populations and local communities so efforts and funds can be allocated to those taxa/ecosystems exhibiting the greatest need. Ecological morphological and functional morphological research form the foundation of our understanding of selection-driven morphological evolution. Studies which identify and describe ecomorphological or functional morphological relationships will improve our fundamental understanding of how taxa respond to ecological selective pressures and will improve our ability to identify and conserve those aspects of nature unable to cope with rapid change. The New World wood warblers (family Parulidae) exhibit extensive taxonomic, behavioral, ecological, and morphological variation. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Wood Warblers Wildlife Note

hooded warbler 47. Wood Warblers Like jewels strewn through the woods, Pennsylvania’s native warblers appear in early spring, the males arrayed in gleaming colors. Twenty-seven warbler species breed commonly in Pennsylvania, another four are rare breeders, and seven migrate through Penn’s Woods headed for breeding grounds farther north. In central Pennsylvania, the first species begin arriving in late March and early April. Louisiana waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla) and black and white warbler (Mniotilta varia) are among the earliest. The great mass of warblers passes through around mid-May, and then the migration trickles off until it ends in late May by which time the trees have leafed out, making it tough to spot canopy-dwelling species. In southern Pennsylvania, look for the migration to begin and end a few days to a week earlier; in northern Pennsylvania, it is somewhat later. As summer progresses and males stop singing on territory, warblers appear less often, making the onset of fall migration difficult to detect. Some species begin moving south as early as mid and late July. In August the majority specific habitat types and show a preference for specific of warblers start moving south again, with migration characteristics within a breeding habitat. They forage from peaking in September and ending in October, although ground level to the treetops and eat mainly small insects stragglers may still come through into November. But by and insect larvae plus a few fruits; some warblers take now most species have molted into cryptic shades of olive flower nectar. When several species inhabit the same area, and brown: the “confusing fall warblers” of field guides. -

Delayed Plumage Maturation and the Presumed Prealternate Molt in American Redstarts

WilsonBull., 95(2), 1983, pp. 199-208 DELAYED PLUMAGE MATURATION AND THE PRESUMED PREALTERNATE MOLT IN AMERICAN REDSTARTS SIEVERT ROHWER, WILLIAM P. KLEIN, JR., AND SCOTT HEARD The American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla) is one of about 30 sexually dichromatic North American passerine species in which males exhibit a delayed plumage maturation (Rohwer et al. 1980). Males in their first win- ter and in their first potential breeding season are largely like females in coloration. These young males have only a few scattered black feathers on their head, hack, and breast, areas where adult males are solid black, and they have yellow rather than the orange patches characteristic of adult males in their wings and tail. Two of four hypotheses reviewed by Rohwer et al. (1980) are relevant to the delay in plumage maturation characteristic of these 30 dichromatic passerine species. Both describe hypothesized best-alternative responses by which young males have minimized their disadvantage in one or both forms of sexual competition. The first, which we here rename, is the Cryptic Hypothesis (CH). Selander (1965) devel- oped this hypothesis by arguing that the costs of a conspicuous breeding plumage would not he repaid in yearling males because of their very lim- ited breeding opportunities. This was called the sexual selection hypoth- esis by Rohwer et al. (1980) and the delayed maturation hypothesis by Procter-Gray and Holmes (1981). The second is the Female Mimicry Hy- pothesis (FMH). Rohwer and his coworkers (Rohwer et al. 1980, Rohwer 1983) developed this hypothesis by arguing that young males increase their chances of obtaining female-worthy territories and breeding as yearlings by mimicking females and, thus, eliciting less aggression from adult males in the early stages of territory establishment. -

American Redstarts

American Redstarts By Mike Scully At the time of this writing (early April), the glorious annual spring migration of songbirds through our area is picking up. Every spring I keep a special eye out for one of my favorite migrants, the American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla). These beautiful warblers flutter actively through the foliage, tail spread, wings drooped, older males clad in black and orange, females and second year males in shades of gray, olive green and yellow. For years, the American Redstart was the only species remaining in the genus Setophaga, until a comprehensive genetic analysis of the Family Parulidae resulted in this genus being grouped with more than 32 species formerly placed in the genus Dendroica and Wilsonia. The name Setophaga was applied to the whole by virtue of seniority. Though now grouped in a large genus, the American Redstart remains an outlier, possessing proportionately large wings, a long tail, and prominent rictal bristles at the base of the relatively wide flat beak, all adaptations to a flycatching mode of foraging. Relatively heavy thigh musculature and long central front toes are apparently adaptations to springing into the air after flying insects. American Redstart by Dan Pancamo The foraging strategy of redstarts differs from that of typical flycatchers. Redstarts employ a more warbler-like maneuver, actively moving through the foliage, making typically short sallies after flying insect prey, and opportunistically gleaning insects from twigs and leaves while hovering or perched. The wings are frequently drooped and the colorful tail spread wide in order to flush insect prey. Among birds in general it is common for sometimes minor differences in coloration to exist, depending on the age of the bird, with full adult plumage not achieved until one or more years of age. -

Unlocking the Black Box of Feather Louse Diversity: a Molecular Phylogeny of the Hyper-Diverse Genus Brueelia Q ⇑ Sarah E

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 94 (2016) 737–751 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Unlocking the black box of feather louse diversity: A molecular phylogeny of the hyper-diverse genus Brueelia q ⇑ Sarah E. Bush a, , Jason D. Weckstein b,1, Daniel R. Gustafsson a, Julie Allen c, Emily DiBlasi a, Scott M. Shreve c,2, Rachel Boldt c, Heather R. Skeen b,3, Kevin P. Johnson c a Department of Biology, University of Utah, 257 South 1400 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA b Field Museum of Natural History, Science and Education, Integrative Research Center, 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605, USA c Illinois Natural History Survey, University of Illinois, 1816 South Oak Street, Champaign, IL 61820, USA article info abstract Article history: Songbirds host one of the largest, and most poorly understood, groups of lice: the Brueelia-complex. The Received 21 May 2015 Brueelia-complex contains nearly one-tenth of all known louse species (Phthiraptera), and the genus Revised 15 September 2015 Brueelia has over 300 species. To date, revisions have been confounded by extreme morphological Accepted 18 September 2015 variation, convergent evolution, and periodic movement of lice between unrelated hosts. Here we use Available online 9 October 2015 Bayesian inference based on mitochondrial (COI) and nuclear (EF-1a) gene fragments to analyze the phylogenetic relationships among 333 individuals within the Brueelia-complex. We show that the genus Keywords: Brueelia, as it is currently recognized, is paraphyletic. Many well-supported and morphologically unified Brueelia clades within our phylogenetic reconstruction of Brueelia were previously described as genera. -

MORPHOLOGICAL and ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION in OLD and NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the College O

MORPHOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IN OLD AND NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Clay E. Corbin August 2002 This dissertation entitled MORPHOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IN OLD AND NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS BY CLAY E. CORBIN has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Associate Professor, Department of Biological Sciences Leslie A. Flemming Dean, College of Arts and Sciences CORBIN, C. E. Ph.D. August 2002. Biological Sciences. Morphological and Ecological Evolution in Old and New World Flycatchers (215pp.) Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In both the Old and New Worlds, independent clades of sit-and-wait insectivorous birds have evolved. These independent radiations provide an excellent opportunity to test for convergent relationships between morphology and ecology at different ecological and phylogenetic levels. First, I test whether there is a significant adaptive relationship between ecology and morphology in North American and Southern African flycatcher communities. Second, using morphological traits and observations on foraging behavior, I test whether ecomorphological relationships are dependent upon locality. Third, using multivariate discrimination and cluster analysis on a morphological data set of five flycatcher clades, I address whether there is broad scale ecomorphological convergence among flycatcher clades and if morphology predicts a course measure of habitat preference. Finally, I test whether there is a common morphological axis of diversification and whether relative age of origin corresponds to the morphological variation exhibited by elaenia and tody-tyrant lineages. -

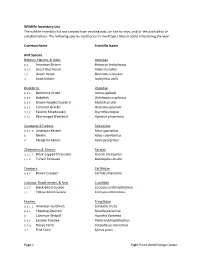

Master Wildlife Inventory List

Wildlife Inventory List The wildlife inventory list was created from existing data, on site surveys, and/or the availability of suitable habitat. The following species could occur in the Project Area at some time during the year: Common Name Scientific Name Bird Species Bitterns, Herons, & Allies Ardeidae D, E American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus A, E, F Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias E, F Green Heron Butorides virescens D Least bittern Ixobrychus exilis Blackbirds Icteridae B, E, F Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula B, E, F Bobolink Dolichonyx oryzivorus B, E, F Brown-headed Cowbird Molothrus ater B, E, F Common Grackle Quiscalus quiscula B, E, F Eastern Meadowlark Sturnella magna B, E, F Red-winged Blackbird Agelaius phoeniceus Caracaras & Falcons Falconidae B, E, F, G American Kestrel Falco sparverius B Merlin Falco columbarius D Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus Chickadees & Titmice Paridae B, E, F, G Black-capped Chickadee Poecile atricapillus E, F, G Tufted Titmouse Baeolophus bicolor Creepers Certhiidae B, E, F Brown Creeper Certhia americana Cuckoos, Roadrunners, & Anis Cuculidae D, E, F Black-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus erythropthalmus E, F Yellow-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus americanus Finches Fringillidae B, E, F, G American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis B, E, F Chipping Sparrow Spizella passerina G Common Redpoll Acanthis flammea B, E, F Eastern Towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus E, F, G House Finch Carpodacus mexicanus B, E Pine Siskin Spinus pinus Page 1 Eight Point Wind Energy Center E, F, G Purple Finch Carpodacus purpureus B, E Red Crossbill