American Redstarts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Redstarts

San Antonio Audubon Society May/June 2021 Newsletter American Redstarts By Mike Scully At the time of this writing (early April), the glorious annual spring migration of songbirds through our area is picking up. Every spring I keep a special eye out for one of my favorite migrants, the American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla). These beautiful warblers flutter actively through the foliage, tail spread, wings drooped, older males clad in black and orange, females and second year males in shades of gray, olive green and yellow. For years, the American Redstart was the only species remaining in the genus Setophaga, until a comprehensive genetic analysis of the Family Parulidae resulted in this genus being grouped with more than 32 species formerly placed in the genus Dendroica and Wilsonia. The name Setophaga was applied to the whole by virtue of seniority. Though now grouped in a large genus, the American Redstart remains an outlier, possessing proportionately large wings, a long tail, and prominent rictal bristles at the base of the relatively wide flat beak, all adaptations to a flycatching mode of foraging. Relatively heavy thigh musculature and long central front toes are apparently adaptations to springing into the air after flying insects. The foraging strategy of redstarts differs from that of typical flycatchers. Redstarts employ a more warbler-like maneuver, actively moving through the foliage, making typically short sallies after flying insect prey, and opportunistically gleaning insects from twigs and leaves while hovering or perched. The wings are frequently drooped and the colorful tail spread wide in order to flush insect prey. -

American Redstart Setophaga Ruticilla

American Redstart Setophaga ruticilla Folk Name: Butterfly Bird, Candelita (Spanish) Status: Migrant and local Breeder Abundance: Common in migration Habitat: Bottomland hardwoods, wide creek floodplains, moist deciduous forest slopes The American Redstart is a spectacular black-and-red- colored bird that is one of our most common migrants and one of the easiest of our warblers to identify. It migrates through this region in good numbers each spring and fall and some stop to breed at scattered locations across both states. The Charlotte News published this description, written by an avid North Carolina birder, on October 11, 1910: Another “find” in which the bird lover takes much pleasure is in the locating of that marvelously colored member of the great Wood Warbler family, the American Redstart. …The great passing flocks of migratory warblers drop the Redstart off each spring on their Northern journey, and pick him up each fall. A full mature male Redstart, which by the way, acquires his plumage only after two years in shrubs or the branches of trees. It’s easy to observe this growth, is truly an exquisite specimen of nature’s behavior while out birding during migration. handiwork. Imagine a wee small bird, smaller than Leverett Loomis reported the redstart as “abundant” a canary, of shining black on breast, throat and back, during spring and fall migration in Chester County while on it wings and tail and sides are patches of during the late 1870s, and one year he collected three bright salmon color. These strangely colored birds males on 17 August. William McIlwaine provided the are called in Cuba “Candelita,” the little torch that first records of the American Redstart in Mecklenburg flames in the gloomy depths of tropical forests. -

Wood Warblers Wildlife Note

hooded warbler 47. Wood Warblers Like jewels strewn through the woods, Pennsylvania’s native warblers appear in early spring, the males arrayed in gleaming colors. Twenty-seven warbler species breed commonly in Pennsylvania, another four are rare breeders, and seven migrate through Penn’s Woods headed for breeding grounds farther north. In central Pennsylvania, the first species begin arriving in late March and early April. Louisiana waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla) and black and white warbler (Mniotilta varia) are among the earliest. The great mass of warblers passes through around mid-May, and then the migration trickles off until it ends in late May by which time the trees have leafed out, making it tough to spot canopy-dwelling species. In southern Pennsylvania, look for the migration to begin and end a few days to a week earlier; in northern Pennsylvania, it is somewhat later. As summer progresses and males stop singing on territory, warblers appear less often, making the onset of fall migration difficult to detect. Some species begin moving south as early as mid and late July. In August the majority specific habitat types and show a preference for specific of warblers start moving south again, with migration characteristics within a breeding habitat. They forage from peaking in September and ending in October, although ground level to the treetops and eat mainly small insects stragglers may still come through into November. But by and insect larvae plus a few fruits; some warblers take now most species have molted into cryptic shades of olive flower nectar. When several species inhabit the same area, and brown: the “confusing fall warblers” of field guides. -

Delayed Plumage Maturation and the Presumed Prealternate Molt in American Redstarts

WilsonBull., 95(2), 1983, pp. 199-208 DELAYED PLUMAGE MATURATION AND THE PRESUMED PREALTERNATE MOLT IN AMERICAN REDSTARTS SIEVERT ROHWER, WILLIAM P. KLEIN, JR., AND SCOTT HEARD The American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla) is one of about 30 sexually dichromatic North American passerine species in which males exhibit a delayed plumage maturation (Rohwer et al. 1980). Males in their first win- ter and in their first potential breeding season are largely like females in coloration. These young males have only a few scattered black feathers on their head, hack, and breast, areas where adult males are solid black, and they have yellow rather than the orange patches characteristic of adult males in their wings and tail. Two of four hypotheses reviewed by Rohwer et al. (1980) are relevant to the delay in plumage maturation characteristic of these 30 dichromatic passerine species. Both describe hypothesized best-alternative responses by which young males have minimized their disadvantage in one or both forms of sexual competition. The first, which we here rename, is the Cryptic Hypothesis (CH). Selander (1965) devel- oped this hypothesis by arguing that the costs of a conspicuous breeding plumage would not he repaid in yearling males because of their very lim- ited breeding opportunities. This was called the sexual selection hypoth- esis by Rohwer et al. (1980) and the delayed maturation hypothesis by Procter-Gray and Holmes (1981). The second is the Female Mimicry Hy- pothesis (FMH). Rohwer and his coworkers (Rohwer et al. 1980, Rohwer 1983) developed this hypothesis by arguing that young males increase their chances of obtaining female-worthy territories and breeding as yearlings by mimicking females and, thus, eliciting less aggression from adult males in the early stages of territory establishment. -

Taxonomic Relationships Among the American Redstarts

TAXONOMIC RELATIONSHIPS AMONG THE AMERICAN REDSTARTS KENNETH C. PARKES N recent years certain bird taxonomists have indulged in what might be I described as a veritable orgy of genus-lumping. Small genera, particularly monotypic genera, must, it seems, be somehow combined with one another, or shoehorned into larger genera (see, for example, the footnote on Uropsila, Paynter, 1960:430). To some extent this is a healthy trend, as many bird families are undeniably oversplit. Much of the recent lumping, however, has a fundamental shortcoming; the authors make little or no effort to re-evaluate the composition of the currently accepted genera before simply emptying the contents of two bureau drawers into one. It is possible, indeed probable, that some of our genera as they now stand are composite and artificial, not reflecting actual relationships. The answer to such problems is not simple lumping, but rather redefinition of genera, with the generic lines drawn in different places. An excellent example is provided by the case history of the North American forest thrushes. Ridgway (1907:19, 35) pointed out many years ago the close relationship between the thrushes generally placed in the two genera Hylocichlu and Cutharus. Ripley (1952), in a paper which advocated merging a number of genera of thrushes, formally proposed the lumping of Hylocichlu and Cutharus under the latter name, but without any analytical study of the species currently placed in these two genera. This proposition had already been made in several unpublished theses dealing with regional avifaunas (Loetscher, 1941:664; Phillips, 1946:309; Parkes, 1952:384), also as a straight lumping of the two genera. -

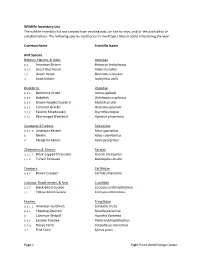

Master Wildlife Inventory List

Wildlife Inventory List The wildlife inventory list was created from existing data, on site surveys, and/or the availability of suitable habitat. The following species could occur in the Project Area at some time during the year: Common Name Scientific Name Bird Species Bitterns, Herons, & Allies Ardeidae D, E American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus A, E, F Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias E, F Green Heron Butorides virescens D Least bittern Ixobrychus exilis Blackbirds Icteridae B, E, F Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula B, E, F Bobolink Dolichonyx oryzivorus B, E, F Brown-headed Cowbird Molothrus ater B, E, F Common Grackle Quiscalus quiscula B, E, F Eastern Meadowlark Sturnella magna B, E, F Red-winged Blackbird Agelaius phoeniceus Caracaras & Falcons Falconidae B, E, F, G American Kestrel Falco sparverius B Merlin Falco columbarius D Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus Chickadees & Titmice Paridae B, E, F, G Black-capped Chickadee Poecile atricapillus E, F, G Tufted Titmouse Baeolophus bicolor Creepers Certhiidae B, E, F Brown Creeper Certhia americana Cuckoos, Roadrunners, & Anis Cuculidae D, E, F Black-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus erythropthalmus E, F Yellow-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus americanus Finches Fringillidae B, E, F, G American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis B, E, F Chipping Sparrow Spizella passerina G Common Redpoll Acanthis flammea B, E, F Eastern Towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus E, F, G House Finch Carpodacus mexicanus B, E Pine Siskin Spinus pinus Page 1 Eight Point Wind Energy Center E, F, G Purple Finch Carpodacus purpureus B, E Red Crossbill -

STABLE HYDROGEN ISOTOPE ANALYSIS of AMERICAN REDSTART RECTRICES Elior Anina, Alessandra Cerio, Ashilly Lopes, Yasmeen Luna, Lauren Puishys

2016 STABLE HYDROGEN ISOTOPE ANALYSIS OF AMERICAN REDSTART RECTRICES Elior Anina, Alessandra Cerio, Ashilly Lopes, Yasmeen Luna, Lauren Puishys A Major Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree in Bachelor of Science in Biology and Biotechnology Project Advisor: Marja Bakermans, BBT Laboratory Advisor: Mike Buckholt Massachusetts State Ornithologist: Andrew C. Vitz This report represents work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects Abstract Understanding avian migration patterns between breeding, stopover, and wintering sites is crucial for the creation of conservation efforts. Stable isotope analysis is rising in popularity due to its ability to track avian migration without the use of satellites and traditional banding methods. Hydrogen isotope signatures vary by latitude due to fractionation during evaporation of ocean water. As warblers molt on their breeding grounds, the hydrogen isotope signatures are incorporated into their growing feathers through trophic-level interactions. We used a stable hydrogen isotope analysis of American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla) rectrices using feather samples collected from the Powdermill Avian Research Center in Pennsylvania. We found no significant difference in δD values and migration timing between the two sample years (2010 and 2011). A significant difference in migratory patterns between adult male and adult female warblers was present, where males appear to migrate before their female counterparts. This pattern may be a result of the need for females to recover after the breeding season and gain fat reserves before strenuous migration. -

American Redstart Purple Finch Yellow Warbler White-Crowned Sparrow

BIRDSWild About Western meadowlark Sturnella neglecta 21–28 cm The western meadowlark is a 2bird of open spaces, such as fields, grasslands or pastures. If your property includes or is adjacent to such areas, be sure to avoid the use of pesticides so meadowlarks can find plenty of insects, such as beetles, cut- American redstart worms, caterpillars and grass- Setophaga ruticilla hoppers. Allow a corner of your property 12–14 cm to go a bit wild so they can also feed on the seeds of weeds and grasses. To attract this striking woodland bird, you will definitely need trees This bird will also use areas of dense vegetation to locate its ground nest, on your property, preferably combined with lots of shrubs. Insects so avoid mowing, especially in the spring. It is very sensitive to human make up the bulk of the American redstart’s diet, so don’t use pesti- disturbance when nesting, so be sure to avoid nesting areas during the cides on the trees where it likes to forage. The redstarts themselves breeding season. will take care of any problem insects, such as leafhoppers or cat- erpillars. In late summer or fall, the fruits of serviceberry or native barberry are a great attraction. This bird likes to nest in deciduous Dark-eyed junco trees or tall shrubs, such as maple, birch, hawthorn or alder. Junco hyemalis 14–16 cm The dark-eyed junco likes to forage for insects and seeds on the ground, staying close to cover for a quick escape from predators. If you want it to feel safe in your gar- den, be sure to add some dense shrubs, especially evergreens like cedar that provide year-round Common redpoll shelter. -

Armbrust Hill Bird Walk

LHA A VE IN N V ARMBRUST HILL BIRD WALK L A T N S D T R U Armbrust Hill is owned by the town of Vinalhaven. There is no parking at the preserve trailhead, please park in town and walk. To see the following songbirds, the oak trees near the trailhead behind the medical center is the best place to look for these woodland birds. Early mornings are best for bird watching, and also a cooler time of day! There are many apps that can help with identification on bird songs. See the walks and talks page for a list of bird apps. Shhh...be quiet. Listen for the birdsong that can identitfy the birds, and avoid scaring them away. Take photos and send them to us! Happy Birding. Vinalhaven Land Trust 12 Skoog Park Vinalhaven Maine 04863 vinalhavenlandtrust.org Northern parula A small warbler of the upper canopy, the northern parula nests can be found in old man’s beard lichen. It hops through branches bursting with a rising buzzy trill that pinches off at the end. Its white eye crescents, chestnut breast band, and yellow-green patch on the back set it apart from other warblers. Photo by Kirk Gentalen. Tennessee warbler A dainty warbler of the Canadian boreal forest, the Tennessee warbler specializes in eating the spruce budworm. Consequently its population goes up and down with fluctuations in the populations of the budworm. Common yellowthroat Common yellowthroats spend much of their time skulking low to the ground in dense thickets and fields, searching for small insects and spiders. -

Parasite Assemblages Distinguish Populations of a Migratory Passerine on Its Breeding Grounds K

Journal of Zoology. Print ISSN 0952-8369 Parasite assemblages distinguish populations of a migratory passerine on its breeding grounds K. L. Durrant1, P. P. Marra2, S. M. Fallon1, G. J. Colbeck3, H. L. Gibbs4, K. A. Hobson5, D. R. Norris6, B. Bernik1, V. L. Lloyd1 & R. C. Fleischer1 1 Genetics Program, Smithsonian Institution, NW, Washington, DC, USA 2 Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, National Zoological Park, NW, Washington, DC, USA 3 School of Biological Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA 4 Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology, The Ohio State University, Aronoff Laboratory, Columbus, OH, USA 5 Environment Canada, Saskatoon, SK, Canada 6 Department of Integrative Biology, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada Keywords Abstract Setophaga ruticilla; migration; Plasmodium; Haemoproteus; avian malaria; blood parasite. We attempted to establish migratory connectivity patterns for American redstarts Setophaga ruticilla between their breeding and wintering grounds by characteriz- Correspondence ing the composition of their haematozoan parasite assemblages in different parts Kate L. Durrant. Current address: of their range. We detected significant but limited geographic structuring of Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, haematozoan parasite lineages across the breeding range of the redstart. We found The University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 that redstarts from the south-eastern (SE) region of the breeding range had a 2TN, UK. significantly different haematozoan parasite assemblage compared with popula- Email: k.l.durrant@sheffield.ac.uk tions sampled throughout the rest of the breeding range. Evidence using stable isotopes from feathers previously demonstrated that redstarts from the SE of the Received 19 July 2007; accepted breeding range also have a unique and separate wintering range. -

American Ornithological Union (AOU) Bird Species List 1

American Ornithological Union (AOU) Bird Species List 1 Alpha Alpha Species Code Species Code Western Grebe WEGR Glaucous-winged Gull GWGU Clark's Grebe CLGR Hybrid Gull HYGU Red-necked Grebe RNGR Great Black-backed Gull GBBG Horned Grebe HOGR Slaty-backed Gull SBGU Eared Grebe EAGR Western Gull WEGU Least Grebe LEGR Yellow-footed Gull YFGU Pied-billed Grebe PBGR Lesser Black-backed Gull LBBG Common Loon COLO Herring Gull HERG Yellow-billed Loon YBLO California Gull CAGU Arctic Loon ARLO Unidentified Gull UNGU Pacific Loon PALO Ring-billed Gull RBGU Red-throated Loon RTLO Band-tailed Gull BTGU Tufted Puffin TUPU Mew Gull MEGU Atlantic Puffin ATPU Black-headed Gull BHGU Horned Puffin HOPU Heermann's Gull HEEG Rhinoceros Auklet RHAU Laughing Gull LAGU Cassin's Auklet CAAU Franklin's Gull FRGU Parakeet Auklet PAAU Bonaparte's Gull BOGU Crested Auklet CRAU Little Gull LIGU Whiskered Auklet WHAU Ross' Gull ROGU Least Auklet LEAU Sabine's Gull SAGU Ancient Murrelet ANMU Gull-billed Tern GBTE Marbled Murrelet MAMU Caspian Tern CATE Kittlitz's Murrelet KIMU Royal Tern ROYT Xantus' Murrelet XAMU Crested Tern CRTE Craveri's Murrelet CRMU Elegant Tern ELTE Black Guillemot BLGU Sandwich Tern SATE Pigeon Guillemot PIGU Cayenne Tern CAYT Common Murre COMU Forster's Tern FOTE Thick-billed Murre TBMU Common Tern COTE Razorbill RAZO Arctic Tern ARTE Dovekie DOVE Roseate Tern ROST Great Skua GRSK Aleutian Tern ALTE South Polar Skua SPSK Black-naped Tern BNTE Pomarine Jaeger POJA Least Tern LETE Parasitic Jaeger PAJA Sooty Tern SOTE Long-tailed Jaeger LTJA -

American Redstart Setophaga Ruticilla ILLINOIS RANGE

American redstart Setophaga ruticilla Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The American redstart averages about five inches in Class: Aves length. The male has black feathers with orange Order: Passeriformes patches on the wings and tail. The female has green- brown feathers with yellow patches on the wings Family: Parulidae and tail. The immature male is colored like the ILLINOIS STATUS female except the wing and tail patches are orange. common, native BEHAVIORS This bird is a common migrant and summer resident ILLINOIS RANGE statewide in Illinois. It winters from the southern United States to South America. Males arrive in Illinois in spring before the females. Nesting occurs from May through July. The nest is placed in the fork of a tree or shrub about four to 30 feet above the ground. The nest is composed of plant materials and is lined with grasses, hair and sometimes feathers. The outside of the nest is covered with lichens, bark, bud scales and other plant materials held together with spider silk. The female builds the nest in about one week. Three to five white eggs with red-brown markings are laid by the female. The incubation period takes 12 to 13 days. One brood per year is raised. Fall migration begins in late July. The redstart can be seen flitting from branch to branch in trees of bottomland woods and other deciduous woods. It droops its wings and fans its tail to show off its colors. This bird sings several songs, the most common being a series of “zee” with the last note higher.