Armenia Tree Project Environmental Education Curriculum 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Yektan Turkyilmaz 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the conflict in Eastern Anatolia in the early 20th century and the memory politics around it. It shows how discourses of victimhood have been engines of grievance that power the politics of fear, hatred and competing, exclusionary -

2. World Bank Assistance to Armenia, 1993-2002

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 1 Acronyms AAA Analyhcal and Advisory Services AR Armenia Railways BTO Back to Office CAE Country Assistance Evaluation CAS Country Assistance Strategy CEM Country Economic Memorandum CIS Commonwealth of Independent States DAC Development Assistance Committee DFID Department for International Development (UK) EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development ECA Europe and Central Asia ECSSD Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development EDP Enterprise Development Project ERP Earthquake Reconstruction Project ESW Economic Sector Work FSU Former Soviet Union FIAS Foreign Investment Advisory Service GDP Gross Domestic Product GOA Government of Armenia IBRD International Bank for Reconstruction and Development IDA International Development Agency IFAD International Fund for Agricultural Development IFC International Finance Corporation IFIS International Financial Institutions IMF International Monetary Fund JBIC Japan Bank for International Cooperation Kfw Kreditanstalt fiir Wiederaufbau (German Agency for Reconstruction) LIL Learning and Innovation Lending MDG Millennium Development Goal MTEF Medium Term Expenditure Framework NK Nagorno Karabakh ODA Official Development Assistance OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development OED Operations Evaluation Development OOF Other Official Flows PER Public Expenditure Review PRSP Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PSD Private Sector Development SAC ' Structural Adjustment Credit SATAC Structural Adjustment Technical Assistance SCADA Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition SIF Social Investment Fund SME Small and Medium Enterprises SOE State Owned Enterprise TA Technical Assistance USAID United States Agency for International Development WB World Bank WTO World Trade Organization ~~ Director-General, Operations Evaluation Mr. Gregory K. Ingram Director, Operations Evaluation Department Mr. Ajay Chhibber Senior Manager, Country Evaluation & Regional Relations Mr. -

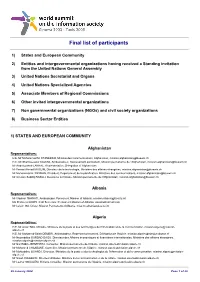

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies -

NEWS INBRIEF Vineyard Taps Into Artsakh's Past to Help Its Future

JUNE 29, 2019 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXIX, NO. 49, Issue 4593 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF UN Questions Mirror-Spectator Turkey on the Fate Annual Summer Break WATERTOWN — The Armenian Mirror-Spectator will close for two weeks in July as part of its annu- Of Armenians al summer break. This issue is the last before the vacation; the first During Genocide edition back would be that of July 20. The office will be closed from July 1 – July 12. NEW YORK — Recently the Holy See of Echmiadzin, the Great House of Cilicia, Armenian Evangelical World Council, the Commissioner of Armenian Missionary Association of America and the AGBU together welcomed Diaspora Gets to Work an effort by various bodies of the United YEREVAN (Armenpress) — High Commissioner for Nations, which called for a probe into the Diaspora Affairs of Armenia Zareh Sinanyan has pre- fate of millions of Armenians who were pared the strategic plan of the structure. forcibly deported by the Ottoman Empire. He told reporters on June 25 that the first step The working group submitted its query of the program is going to be the work with the to the UN office in Geneva on March 25. Armenian community of Russia. It is signed by Bernard Duhaime, Chair- Alex and Talar Sarafian with two of their children in the vineyard “This community is the largest and the most spread geographically. It has the most ties with Vineyard Taps into Artsakh’s Armenia both psychologically and physically. -

History Stands to Repeat Itself As Armenia Renews Ties to Asia

THE ARMENIAN GENEALOGY MOVEMENT P.38 ARMENIAN GENERAL BENEVOLENT UNION AUG. 2019 History stands to repeat itself as Armenia renews ties to Asia Armenian General Benevolent Union ESTABLISHED IN 1906 Հայկական Բարեգործական Ընդհանուր Միութիւն Central Board of Directors President Mission Berge Setrakian To promote the prosperity and well-being of all Armenians through educational, Honorary Member cultural, humanitarian, and social and economic development programs, projects His Holiness Karekin II, and initiatives. Catholicos of All Armenians Annual International Budget Members USD UNITED STATES Forty-six million dollars ( ) Haig Ariyan Education Yervant Demirjian 24 primary, secondary, preparatory and Saturday schools; scholarships; alternative Eric Esrailian educational resources (apps, e-books, AGBU WebTalks and more); American Nazareth A. Festekjian University of Armenia (AUA); AUA Extension-AGBU Artsakh Program; Armenian Arda Haratunian Virtual College (AVC); TUMO x AGBU Sarkis Jebejian Ari Libarikian Cultural, Humanitarian and Religious Ani Manoukian AGBU News Magazine; the AGBU Humanitarian Emergency Relief Fund for Syrian Lori Muncherian Armenians; athletics; camps; choral groups; concerts; dance; films; lectures; library research Levon Nazarian centers; medical centers; mentorships; music competitions; publications; radio; scouts; Yervant Zorian summer internships; theater; youth trips to Armenia. Armenia: Holy Etchmiadzin; AGBU ARMENIA Children’s Centers (Arapkir, Malatya, Nork), and Senior Dining Centers; Hye Geen Vasken Yacoubian -

THE ARMENIAN Ctator Volume LXXXVII, NO

JUNE 10, 2017 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXVII, NO. 47, Issue 4491 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF ICG: Armenia, Azerbaijan Closer to War Over Nagorno- Georgia, Azerbaijan and Turkey to Hold Military Karabakh Than at Any Time Since 1994 Drills of the conflict in the South Caucasus, findings of analysts who had talked to resi- TBILISI (Anadoou) — Tbilisi will host military By Margarita Antidze which is criss-crossed by oil and gas dents and observers on the ground, said drills held jointly by Georgia, Azerbaijan and pipelines, have failed despite mediation led the settlement process had stalled, making Turkey this past week, the Georgian Defense by France, Russia and the United States, the use of force tempting, at least for tacti- Ministry reported. TBILISI (Reuters) — The former Soviet cal purposes, and both The Caucasus Eagle drills have been held since republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan are sides appeared ready 2009. This is the third time the exercises have been closer to war over Nagorno-Karabakh than for confrontation. held in the trilateral format. at any point since a ceasefire brokered “These tensions Earlier this May, the defense ministers of the more than 20 years ago, the International could develop into larg- three countries signed a joint statement indicating Crisis Group (ICG) said. er-scale conflict, lead- the parties’ willingness to continue efforts on Fighting between ethnic Azeris and ing to significant civil- securing stability and peace and recognizing the Armenians first erupted in 1991 and a ian casualties and pos- territorial integrity of each of the three countries. -

Political Rallies to Conventions

Sergey Minasyan FROM POLITICAL RALLIES TO CONVENTIONS POLITICAL AND LEGAL ASPECTS OF PROTECTING THE RIGHTS OF THE ARMENIAN ETHNIC MINORITY IN GEORGIA AS EXEMPLIFIED BY THE SAMTSKHE-JAVAKHETI REGION Yerevan 2007 ê»ñ·»Û ØÇݳëÛ³Ý ø²Ô²ø²Î²Ü òàôÚòºðÆò ¸ºäÆ Ð²Ø²Ò²Úܲ¶ðºð ìð²êî²ÜÆ Ð²Ú ¾ÂÜÆÎ²Î²Ü öàøð²Ø²êÜàôÂÚ²Ü Æð²ìàôÜøܺðÆ ä²Þîä²ÜàôÂÚ²Ü ø²Ô²ø²Î²Ü ºì Æð²ì²Î²Ü ²êäºÎîܺðÀ ê²Øòʺ-æ²ì²ÊøÆ î²ð²Ì²Þðæ²ÜÆ úðÆܲÎàì ºñ¨³Ý 2007 Ðî¸ (341.231.14) ¶Øä (6791) Ø-710 Minasyan, S. From Political Rallies to Conventions: Political and Legal Aspects of Protecting the Rights of the Armenian Ethnic Minority in Georgia as Exemplified by the Samtskhe-Javakheti Region. – Yerevan, CMI and the ‘Yerkir’ NGO Union, 2007. – p. 92. The volume analyses the situation with human and minority rights in Georgia and suggests ways of integrating minorities in the social, political and cultural life of the country. The author looks at the legal framework for minority issues, focusing on Georgia’s international legal obligations and their political implementation practices. In a case study of the Armenian-populated region of Samtskhe-Javakheti, the author proposes mechanisms and recommendations for achieving a compromise between minorities’ needs to preserve their identity, language and culture, and to achieve factual political rights, on one hand, and their profound civil integration, on the other. Scientific Editor: A. Iskandaryan Editors: H. Kharatyan, N. Iskandaryan, R. Tatoyan Translation from Russian: V. Kisin English version editor: N. Iskandaryan Cover photo by R. -

Download the Publication

Contents WHO WE ARE ............................................. 7 Vision and Strategy ............................................7 The Team .........................................................12 Achievements ...................................................12 ICHD Core Staff ...............................................14 WHAT WE DO .............................................16 ICHD Toolbox ...................................................16 Internship with ICHD .......................................20 Financial Report ...............................................21 PROJECTS REVIEW .................................. 25 PHOTOS .................................................... 113 OUR CONTACTS .......................................136 The International Center for Human Development is ten years old. This publica- - presentedtion briefly by summarizes an international its activities audit. throughout past decade. It highlights our ma jor achievements, key activities and implemented projects and the financial report In ten years, the Center has carried out hundreds of initiatives and projects, such as research studies and educational projects, more than ten international conferences on various issues, hosted hundreds of off-the-record roundtables with the involvement of international and domestic analysts and experts, issued more than 100 “Policy Briefs” and “Viewpoints”. Within last two years three laws drafted by the - uctsICHD include have been the circulatedConcept on officially, Development one receiving of Armenia-Diaspora -

Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia: Political Developments and Implications for U.S

Order Code IB95024 Issue Brief for Congress Received through the CRS Web Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia: Political Developments and Implications for U.S. Interests Updated January 23, 2003 Jim Nichol Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress CONTENTS SUMMARY MOST RECENT DEVELOPMENTS BACKGROUND AND ANALYSIS Overview of U.S. Policy Concerns Obstacles to Peace and Independence Regional Tensions and Conflicts Nagorno Karabakh Conflict Civil and Ethnic Conflict in Georgia Economic Conditions, Blockades and Stoppages Political Developments Armenia Azerbaijan Georgia The South Caucasus’ External Security Context Russian Involvement in the Region Military-Strategic Interests Caspian Energy Resources The Protection of Ethnic Russians and “Citizens” The Roles of Turkey, Iran, and Others Aid Overview U.S. Security Assistance U.S. Trade and Investment Energy Resources and U.S. Policy IB95024 01-23-03 Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia: Political Developments and Implications for U.S. Interests SUMMARY The United States recognized the inde- aid, border security and customs support to pendence of all the former Soviet republics by promote non- proliferation, Trade and Devel- the end of 1991, including the South Caucasus opment Agency aid, Overseas Private Invest- states of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. ment Corporation insurance, Eximbank fi- The United States has fostered these states’ nancing, and Foreign Commercial Service ties with the West, including membership in activities. The current Bush Administration the Organization on Security and Cooperation appealed for a national security waiver of the in Europe and NATO’s Partnership for Peace, prohibition on aid to Azerbaijan, in consider- in part to end the dependence of these states ation of Azerbaijan’s assistance to the interna- on Russia for trade, security, and other rela- tional coalition to combat terrorism. -

All-Armenian Fund Raises Big Bucks at Thanksgiving Telethon

DECEMBER 3, 2011 MirTHE rARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXII, NO. 21, Issue 4215 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Pop Star Sylvie Vartan All-Armenian Fund Raises Big Says She Is Armenian PARIS — French pop star Sylvie Vartan said for the first time on the show “Vivement dimanche” that she was of Armenian descent through her father, Bucks at Thanksgiving Telethon Georges Vartan, former press officer at Embassy of France in Sofia; this was the singer’s first public LOS ANGELES — In an annual telethon statement on her Armenian heritage. broadcast from Los Angeles late on Asked a question by Michel Drucker, on Thanksgiving Day, the Yerevan-based “Vivement dimanche,” the singer replied, “Yes, I’m Hayastan All-Armenian Fund (Himnadram) Armenian [on the] side of my father.” sponsored its annual telethon, during Born in Bulgaria on August 15, 1944 (her moth - which the organization received $12.3 mil - er is Bulgarian), she arrived in Paris on December lion in pledges. This year, as in last, the 1952 with her parents. funds will be used primarily toward the She started in show business at 16, and immedi - reconstruction of Nagorno-Karabagh’s ately became successful with a song by Charles water distribution network. Aznavour and Georges Garvarentz, La plus belle Final figures may prove to be higher after pour aller danser (The most beautiful to go dancing). it completes the tabulation of donation Her son, David Hallyday, is also a pop star in pledges received from Armenians in the France. -

Համահայկական Հիմնադրամ HAYASTAN All-Armenian Fund

ՀԱՅԱՍՏԱՆ համահայկական հիմնադրամ HAYASTAN All-Armenian Fund 2019 ՀԱՅԱՍՏԱՆ համահայկական հիմնադրամ HAYASTAN All-Armenian Fund Հրատարակիչ՝ «Հայաստան» համահայկական հիմնադրամ Published by Hayastan All-Armenian Fund Պատմությունները՝ Արմեն Օհանյանի Stories by Armen Ohanyan Լուսանկարները՝ Արեգ Բալայանի Էմմա Բրաունի Photos by Areg Balayan Emma Brown Ձևավորումը՝ Էդիկ Պողոսյանի Designed by Edik Boghosian Տպագրվել է «Թոփ պրինտ» տպագրատանը Printed by “Top Print” printing house ԲՈՎԱՆԴԱԿՈՒԹՅՈՒՆ CONTENTS Հոգաբարձուների խորհուրդ 6 Board of trustees 8 Գործադիր տնօրենի խոսքը Executive director’s message 11 Պատումներ Stories Վա հան չոյենց նոր տու նը The Grigoryans’ new home 16 « Մեր տու նը» Չա փա րում “Our home” in Chapar 30 Բժշ կա կան ա ռա քե լությունն Ար ցա խում Medical mission to Artsakh 42 Տի րա մայր Նա րե կը Tiramayr Narek hospital 54 Շո շի վե րել քը The growth of Shosh 68 Նոր Հայաս տա նին հա րիր նոր ման կա պար տեզ A new kindergarten fit for the new Armenia 78 Ա ջակ ցություն «ս մարթ» ար ցախ ցուն Boosting Artsakh’s emerging tech sector 90 Ա րևային Քարին տակը Karin tak, powered by the sun 100 Ա րևային Տա վուշ Solar Tavush 112 Ճա նա պարհ դե պի Մա տա ղիս The road to Mataghis 124 Բռնությանը ոչ ենք ասում We’re saying no to violence 132 Ամենամյա Annual 147 Ֆինանսական հաշվետվություն Financial report 153 Ծրագրեր Projects 167 Ոսկե մատյան Golden Book 183 «Հայաստան» համահայկական հիմնադրամի ՀՈԳԱԲԱՐՁՈՒՆԵՐԻ ԽՈՐՀՈՒՐԴ Արմեն Սարգսյան ՀՀ նախագահ, «Հայաստան» համահայկական հիմնադրամի հոգաբարձուների խորհրդի նախագահ Նիկոլ Փաշինյան ՀՀ վարչապետ Արարատ Միրզոյան ՀՀ Ազգային ժողովի նախագահ Բակո Սահակյան Արցախի Հանրապետության նախագահ Արկադի Ղուկասյան Արցախի Հանրապետության պաշտոնաթող նախագահ, «Հայաստան» համահայկական հիմնադրամի փոխնախագահ Հրայր Թովմասյան ՀՀ սահմանադրական դատարանի նախագահ, «Հայաստան» համահայկական հիմնադրամի հոգաբարձուների խորհրդի փոխնախագահ Ն.Ս.Օ.Տ.Տ Գարեգին Բ Ամենայն Հայոց Կաթողիկոս Ն.Ս.Օ.Տ.Տ Արամ Ա Մեծի Տանն Կիլիկիո Կաթողիկոս Գրիգոր Պետրոս Հայ Կաթողիկե եկեղեցու Կաթողիկոս Պատրիարք Ի. -

In a Letter to His Brother Krikor

The Armenian Weekly APRIL 2016 101 1_cover.indd 1 8/27/16 11:14 AM Editorial and sponsors_Layout 1 5/16/16 7:45 PM Page 3 The Armenian Weekly APRIL 2016 NOTES BOOK REVIEW 5 Contributors 35 The Armenian Genocide in the American Humanitarian 7 Editor’s Desk Imagination: A Review of “Bread from Stones: The Middle RESEARCH East and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism’ —By Elyse Semerdjian 8 China as Refuge for Armenian Genocide Survivors —By Khatchig Mouradian COMMENTARY 13 Imperial Russia’s Response to the Armenian Genocide and the Refugee Crisis on the Caucasus Battlefront of World 37 Artsakh Is Our Nation’s 21st Century Sardarabad War I —By Asya Darbinyan —By Michael G. Mensoian 19 A Glimpse into the Life of the Armenian DPs in Europe 40 Bearing Witness in the Aftermath of the Armenian —By Knarik O. Meneshian Genocide—By Armen T. Marsoobian 25 Rescuing Armenian Women and Children After the 45 Dispatch from Istanbul: Nine Years in the Courtrooms: Genocide: The Story of Ruben Heryan The Murder Cases of Dink, Balikci, and Kucuk —By Anna Aleksanyan —By Sayat Tekir 30 ‘Memories of a Turkish Statesman—1913–19’: A Reflection on Cemal Pasha’s Memoirs —By Varak Ketsemanian ON THE COVER: Lake Van through the crumbling wall of the ancient Armenian Monastery of St. Thomas, built in the 10th–11th centuries (Photo: Nanore Barsoumian) The Armenian Weekly The Armenian Weekly ENGLISH SECTION THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY The opinions expressed in this April 2016 Editor: Nanore Barsoumian (ISSN 0004-2374) newspaper, other than in the editorial column, do not Proofreader: Nayiri Arzoumanian is published weekly by the Hairenik Association, Inc., necessarily reflect the views of Art Director: Gina Poirier 80 Bigelow Ave, THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY.