Arxiv:1802.07727V1 [Astro-Ph.HE] 21 Feb 2018 Tion Systems to Standard Candles in Cosmology (E.G., Wijers Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Revised View of the Canis Major Stellar Overdensity with Decam And

MNRAS 501, 1690–1700 (2021) doi:10.1093/mnras/staa2655 Advance Access publication 2020 October 14 A revised view of the Canis Major stellar overdensity with DECam and Gaia: new evidence of a stellar warp of blue stars Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/501/2/1690/5923573 by Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas (CSIC) user on 15 March 2021 Julio A. Carballo-Bello ,1‹ David Mart´ınez-Delgado,2 Jesus´ M. Corral-Santana ,3 Emilio J. Alfaro,2 Camila Navarrete,3,4 A. Katherina Vivas 5 and Marcio´ Catelan 4,6 1Instituto de Alta Investigacion,´ Universidad de Tarapaca,´ Casilla 7D, Arica, Chile 2Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa, CSIC, E-18080 Granada, Spain 3European Southern Observatory, Alonso de Cordova´ 3107, Casilla 19001, Santiago, Chile 4Millennium Institute of Astrophysics, Santiago, Chile 5Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, NSF’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory, Casilla 603, La Serena, Chile 6Instituto de Astrof´ısica, Facultad de F´ısica, Pontificia Universidad Catolica´ de Chile, Av. Vicuna˜ Mackenna 4860, 782-0436 Macul, Santiago, Chile Accepted 2020 August 27. Received 2020 July 16; in original form 2020 February 24 ABSTRACT We present the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) imaging combined with Gaia Data Release 2 (DR2) data to study the Canis Major overdensity. The presence of the so-called Blue Plume stars in a low-pollution area of the colour–magnitude diagram allows us to derive the distance and proper motions of this stellar feature along the line of sight of its hypothetical core. The stellar overdensity extends on a large area of the sky at low Galactic latitudes, below the plane, and in the range 230◦ <<255◦. -

Constructing a Galactic Coordinate System Based on Near-Infrared and Radio Catalogs

A&A 536, A102 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201116947 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Constructing a Galactic coordinate system based on near-infrared and radio catalogs J.-C. Liu1,2,Z.Zhu1,2, and B. Hu3,4 1 Department of astronomy, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, PR China e-mail: [jcliu;zhuzi]@nju.edu.cn 2 key Laboratory of Modern Astronomy and Astrophysics (Nanjing University), Ministry of Education, Nanjing 210093, PR China 3 Purple Mountain Observatory, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, PR China 4 Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, PR China e-mail: [email protected] Received 24 March 2011 / Accepted 13 October 2011 ABSTRACT Context. The definition of the Galactic coordinate system was announced by the IAU Sub-Commission 33b on behalf of the IAU in 1958. An unrigorous transformation was adopted by the Hipparcos group to transform the Galactic coordinate system from the FK4-based B1950.0 system to the FK5-based J2000.0 system or to the International Celestial Reference System (ICRS). For more than 50 years, the definition of the Galactic coordinate system has remained unchanged from this IAU1958 version. On the basis of deep and all-sky catalogs, the position of the Galactic plane can be revised and updated definitions of the Galactic coordinate systems can be proposed. Aims. We re-determine the position of the Galactic plane based on modern large catalogs, such as the Two-Micron All-Sky Survey (2MASS) and the SPECFIND v2.0. This paper also aims to propose a possible definition of the optimal Galactic coordinate system by adopting the ICRS position of the Sgr A* at the Galactic center. -

The Kinematics of Warm Ionized Gas in the Fourth Galactic Quadrant Martin C

The Kinematics of Warm Ionized Gas in the Fourth Galactic Quadrant Martin C. Gostisha, Robert A. Benjamin (University of Wisconsin-Whitewater), L.M. Haffner (University of Wisconsin- Madison), Alex Hill (CSIRO), and Kat Barger (University of Notre Dame) Abstract: We present an preliminary analysis oF an on-going Wisconsin H-Alpha Mapper (WHAM) survey oF the Fourth quadrant oF the Galac>c plane in diffuse emission From [S II] 6716 A, covering the Fourth galac>c quadrant (Galac>c longitude = 270-360 degrees) and Galac>c latude |b| < 12 degrees. Because oF the high atomic mass and narrow thermal line widths oF sulFur (as compared to hydrogen or nitrogen, this emission line serves as the best tracer oF the kinemacs oF the warm ionized medium in the mid plane oF the Galaxy. We detect extensive emission at veloci>es as negave as -100 km/s indicang that we are seeing much Further into the center oF the Milky Way than was Found For the first quadrant. We discuss constraints on the velocity and ver>cal density structure oF this gas, and compare this distribu>on with what is observed in CO and HI surveys. This work was par>ally supported by the Naonal Science Foundaon’s REU program through NSF award AST-1004881. [SII] provides beNer velocity resolu3on than H-Alpha V The equaon, __________ LSR 40 30 30 gives us a physical value For the line widths oF both H-Alpha and [SII], varying only by the mass oF the individual atoms. Assuming that the gas is at a temperature oF 4 10 T=10 K, the velocity widths oF H-Alpha and [SII], respec>vely, are 20 0 km s-1 10 -10 Figure 2. -

Spatial Distribution of Galactic Globular Clusters: Distance Uncertainties and Dynamical Effects

Juliana Crestani Ribeiro de Souza Spatial Distribution of Galactic Globular Clusters: Distance Uncertainties and Dynamical Effects Porto Alegre 2017 Juliana Crestani Ribeiro de Souza Spatial Distribution of Galactic Globular Clusters: Distance Uncertainties and Dynamical Effects Dissertação elaborada sob orientação do Prof. Dr. Eduardo Luis Damiani Bica, co- orientação do Prof. Dr. Charles José Bon- ato e apresentada ao Instituto de Física da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul em preenchimento do requisito par- cial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Física. Porto Alegre 2017 Acknowledgements To my parents, who supported me and made this possible, in a time and place where being in a university was just a distant dream. To my dearest friends Elisabeth, Robert, Augusto, and Natália - who so many times helped me go from "I give up" to "I’ll try once more". To my cats Kira, Fen, and Demi - who lazily join me in bed at the end of the day, and make everything worthwhile. "But, first of all, it will be necessary to explain what is our idea of a cluster of stars, and by what means we have obtained it. For an instance, I shall take the phenomenon which presents itself in many clusters: It is that of a number of lucid spots, of equal lustre, scattered over a circular space, in such a manner as to appear gradually more compressed towards the middle; and which compression, in the clusters to which I allude, is generally carried so far, as, by imperceptible degrees, to end in a luminous center, of a resolvable blaze of light." William Herschel, 1789 Abstract We provide a sample of 170 Galactic Globular Clusters (GCs) and analyse its spatial distribution properties. -

The Large Scale Universe As a Quasi Quantum White Hole

International Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Journal 3(1): 22-42, 2021; Article no.IAARJ.66092 The Large Scale Universe as a Quasi Quantum White Hole U. V. S. Seshavatharam1*, Eugene Terry Tatum2 and S. Lakshminarayana3 1Honorary Faculty, I-SERVE, Survey no-42, Hitech city, Hyderabad-84,Telangana, India. 2760 Campbell Ln. Ste 106 #161, Bowling Green, KY, USA. 3Department of Nuclear Physics, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam-03, AP, India. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Author UVSS designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors ETT and SL managed the analyses of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information Editor(s): (1) Dr. David Garrison, University of Houston-Clear Lake, USA. (2) Professor. Hadia Hassan Selim, National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics, Egypt. Reviewers: (1) Abhishek Kumar Singh, Magadh University, India. (2) Mohsen Lutephy, Azad Islamic university (IAU), Iran. (3) Sie Long Kek, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Malaysia. (4) N.V.Krishna Prasad, GITAM University, India. (5) Maryam Roushan, University of Mazandaran, Iran. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/66092 Received 17 January 2021 Original Research Article Accepted 23 March 2021 Published 01 April 2021 ABSTRACT We emphasize the point that, standard model of cosmology is basically a model of classical general relativity and it seems inevitable to have a revision with reference to quantum model of cosmology. Utmost important point to be noted is that, ‘Spin’ is a basic property of quantum mechanics and ‘rotation’ is a very common experience. -

Pos(MULTIF2017)001

Multifrequency Astrophysics (A pillar of an interdisciplinary approach for the knowledge of the physics of our Universe) ∗† Franco Giovannelli PoS(MULTIF2017)001 INAF - Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Via del Fosso del Cavaliere, 100, 00133 Roma, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Lola Sabau-Graziati INTA- Dpt. Cargas Utiles y Ciencias del Espacio, C/ra de Ajalvir, Km 4 - E28850 Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain E-mail: [email protected] We will discuss the importance of the "Multifrequency Astrophysics" as a pillar of an interdis- ciplinary approach for the knowledge of the physics of our Universe. Indeed, as largely demon- strated in the last decades, only with the multifrequency observations of cosmic sources it is possible to get near the whole behaviour of a source and then to approach the physics governing the phenomena that originate such a behaviour. In spite of this, a multidisciplinary approach in the study of each kind of phenomenon occurring in each kind of cosmic source is even more pow- erful than a simple "astrophysical approach". A clear example of a multidisciplinary approach is that of "The Bridge between the Big Bang and Biology". This bridge can be described by using the competences of astrophysicists, planetary physicists, atmospheric physicists, geophysicists, volcanologists, biophysicists, biochemists, and astrobiophysicists. The unification of such com- petences can provide the intellectual framework that will better enable an understanding of the physics governing the formation and structure of cosmic objects, apparently uncorrelated with one another, that on the contrary constitute the steps necessary for life (e.g. Giovannelli, 2001). -

Modeling and Interpretation of the Ultraviolet Spectral Energy Distributions of Primeval Galaxies

Ecole´ Doctorale d'Astronomie et Astrophysique d'^Ile-de-France UNIVERSITE´ PARIS VI - PIERRE & MARIE CURIE DOCTORATE THESIS to obtain the title of Doctor of the University of Pierre & Marie Curie in Astrophysics Presented by Alba Vidal Garc´ıa Modeling and interpretation of the ultraviolet spectral energy distributions of primeval galaxies Thesis Advisor: St´ephane Charlot prepared at Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris, CNRS (UMR 7095), Universit´ePierre & Marie Curie (Paris VI) with financial support from the European Research Council grant `ERC NEOGAL' Composition of the jury Reviewers: Alessandro Bressan - SISSA, Trieste, Italy Rosa Gonzalez´ Delgado - IAA (CSIC), Granada, Spain Advisor: St´ephane Charlot - IAP, Paris, France President: Patrick Boisse´ - IAP, Paris, France Examinators: Jeremy Blaizot - CRAL, Observatoire de Lyon, France Vianney Lebouteiller - CEA, Saclay, France Dedicatoria v Contents Abstract vii R´esum´e ix 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Historical context . .4 1.2 Early epochs of the Universe . .5 1.3 Galaxytypes ......................................6 1.4 Components of a Galaxy . .8 1.4.1 Classification of stars . .9 1.4.2 The ISM: components and phases . .9 1.4.3 Physical processes in the ISM . 12 1.5 Chemical content of a galaxy . 17 1.6 Galaxy spectral energy distributions . 17 1.7 Future observing facilities . 19 1.8 Outline ......................................... 20 2 Modeling spectral energy distributions of galaxies 23 2.1 Stellar emission . 24 2.1.1 Stellar population synthesis codes . 24 2.1.2 Evolutionary tracks . 25 2.1.3 IMF . 29 2.1.4 Stellar spectral libraries . 30 2.2 Absorption and emission in the ISM . 31 2.2.1 Photoionization code: CLOUDY ....................... -

LIST of PUBLICATIONS Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences ARIES (An Autonomous Scientific Research Institute

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences ARIES (An Autonomous Scientific Research Institute of Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India) Manora Peak, Naini Tal - 263 129, India (1955−2020) ABBREVIATIONS AA: Astronomy and Astrophysics AASS: Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series ACTA: Acta Astronomica AJ: Astronomical Journal ANG: Annals de Geophysique Ap. J.: Astrophysical Journal ASP: Astronomical Society of Pacific ASR: Advances in Space Research ASS: Astrophysics and Space Science AE: Atmospheric Environment ASL: Atmospheric Science Letters BA: Baltic Astronomy BAC: Bulletin Astronomical Institute of Czechoslovakia BASI: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India BIVS: Bulletin of the Indian Vacuum Society BNIS: Bulletin of National Institute of Sciences CJAA: Chinese Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics CS: Current Science EPS: Earth Planets Space GRL : Geophysical Research Letters IAU: International Astronomical Union IBVS: Information Bulletin on Variable Stars IJHS: Indian Journal of History of Science IJPAP: Indian Journal of Pure and Applied Physics IJRSP: Indian Journal of Radio and Space Physics INSA: Indian National Science Academy JAA: Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy JAMC: Journal of Applied Meterology and Climatology JATP: Journal of Atmospheric and Terrestrial Physics JBAA: Journal of British Astronomical Association JCAP: Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics JESS : Jr. of Earth System Science JGR : Journal of Geophysical Research JIGR: Journal of Indian -

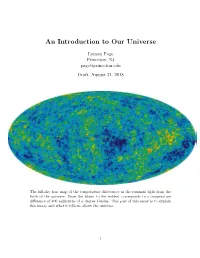

An Introduction to Our Universe

An Introduction to Our Universe Lyman Page Princeton, NJ [email protected] Draft, August 31, 2018 The full-sky heat map of the temperature differences in the remnant light from the birth of the universe. From the bluest to the reddest corresponds to a temperature difference of 400 millionths of a degree Celsius. The goal of this essay is to explain this image and what it tells us about the universe. 1 Contents 1 Preface 2 2 Introduction to Cosmology 3 3 How Big is the Universe? 4 4 The Universe is Expanding 10 5 The Age of the Universe is Finite 15 6 The Observable Universe 17 7 The Universe is Infinite ?! 17 8 Telescopes are Like Time Machines 18 9 The CMB 20 10 Dark Matter 23 11 The Accelerating Universe 25 12 Structure Formation and the Cosmic Timeline 26 13 The CMB Anisotropy 29 14 How Do We Measure the CMB? 36 15 The Geometry of the Universe 40 16 Quantum Mechanics and the Seeds of Cosmic Structure Formation. 43 17 Pulling it all Together with the Standard Model of Cosmology 45 18 Frontiers 48 19 Endnote 49 A Appendix A: The Electromagnetic Spectrum 51 B Appendix B: Expanding Space 52 C Appendix C: Significant Events in the Cosmic Timeline 53 D Appendix D: Size and Age of the Observable Universe 54 1 1 Preface These pages are a brief introduction to modern cosmology. They were written for family and friends who at various times have asked what I work on. The goal is to convey a geometrical picture of how to think about the universe on the grandest scales. -

The Study of Astronomical Transients in the Infrared

The Study of Astronomical Transients in the Infrared by Robert Strausbaugh A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved May 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Nathaniel Butler, Chair Rolf Jansen Phillip Mauskopf Rogier Windhorst ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY August 2019 ©2019 Robert Strausbaugh All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Several key, open questions in astrophysics can be tackled by searching for and mining large datasets for transient phenomena. The evolution of massive stars and compact objects can be studied over cosmic time by identifying supernovae (SNe) and gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) in other galaxies and determining their redshifts. Modeling GRBs and their afterglows to probe the jets of GRBs can shed light on the emission mechanism, rate, and energetics of these events. In Chapter 1, I discuss the current state of astronomical transient study, including sources of interest, instrumentation, and data reduction techniques, with a focus on work in the infrared. In Chapter 2, I present original work published in the Proceedings of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, testing InGaAs infrared detectors for astronomical use (Strausbaugh, Jackson, and Butler 2018); highlights of this work include observing the exoplanet transit of HD189773B, and detecting the nearby supernova SN2016adj with an InGaAs detector mounted on a small telescope at ASU. In Chapter 3, I discuss my work on GRB jets published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, highlighting the interesting case of GRB 160625B (Strausbaugh et al. 2019), where I interpret a late-time bump in the GRB afterglow lightcurve as evidence for a bright-edged jet. -

Monthly Newsletter of the Durban Centre - March 2018

Page 1 Monthly Newsletter of the Durban Centre - March 2018 Page 2 Table of Contents Chairman’s Chatter …...…………………….……….………..….…… 3 Andrew Gray …………………………………………...………………. 5 The Hyades Star Cluster …...………………………….…….……….. 6 At the Eye Piece …………………………………………….….…….... 9 The Cover Image - Antennae Nebula …….……………………….. 11 Galaxy - Part 2 ….………………………………..………………….... 13 Self-Taught Astronomer …………………………………..………… 21 The Month Ahead …..…………………...….…….……………..…… 24 Minutes of the Previous Meeting …………………………….……. 25 Public Viewing Roster …………………………….……….…..……. 26 Pre-loved Telescope Equipment …………………………...……… 28 ASSA Symposium 2018 ………………………...……….…......…… 29 Member Submissions Disclaimer: The views expressed in ‘nDaba are solely those of the writer and are not necessarily the views of the Durban Centre, nor the Editor. All images and content is the work of the respective copyright owner Page 3 Chairman’s Chatter By Mike Hadlow Dear Members, The third month of the year is upon us and already the viewing conditions have been more favourable over the last few nights. Let’s hope it continues and we have clear skies and good viewing for the next five or six months. Our February meeting was well attended, with our main speaker being Dr Matt Hilton from the Astrophysics and Cosmology Research Unit at UKZN who gave us an excellent presentation on gravity waves. We really have to be thankful to Dr Hilton from ACRU UKZN for giving us his time to give us presentations and hope that we can maintain our relationship with ACRU and that we can draw other speakers from his colleagues and other research students! Thanks must also go to Debbie Abel and Piet Strauss for their monthly presentations on NASA and the sky for the following month, respectively. -

The SAI Catalog of Supernovae and Radial Distributions of Supernovae

Astronomy Letters, Vol. 30, No. 11, 2004, pp. 729–736. Translated from Pis’ma v Astronomicheski˘ı Zhurnal, Vol. 30, No. 11, 2004, pp. 803–811. Original Russian Text Copyright c 2004 by Tsvetkov, Pavlyuk, Bartunov. TheSAICatalogofSupernovaeandRadialDistributions of Supernovae of Various Types in Galaxies D. Yu. Tsvetkov*, N.N.Pavlyuk**,andO.S.Bartunov*** Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Universitetski ˘ı pr. 13, Moscow, 119992 Russia Received May 18, 2004 Abstract—We describe the Sternberg Astronomical Institute (SAI)catalog of supernovae. We show that the radial distributions of type-Ia, type-Ibc, and type-II supernovae differ in the central parts of spiral galaxies and are similar in their outer regions, while the radial distribution of type-Ia supernovae in elliptical galaxies differs from that in spiral and lenticular galaxies. We give a list of the supernovae that are farthest from the galactic centers, estimate their relative explosion rate, and discuss their possible origins. c 2004MAIK “Nauka/Interperiodica”. Key words: astronomical catalogs, supernovae, observations, radial distributions of supernovae. INTRODUCTION be found on the Internet. The most complete data are contained in the list of SNe maintained by the Cen- In recent years, interest in studying supernovae (SNe)has increased signi ficantly. Among other rea- tral Bureau of Astronomical Telegrams (http://cfa- sons, this is because SNe Ia are used as “standard www.harvard.edu/cfa/ps/lists/Supernovae.html)and candles” for constructing distance scales and for cos- the electronic version of the Asiago catalog mological studies, and because SNe Ibc may be re- (http://web.pd.astro.it/supern). lated to gamma ray bursts.