Scene on Radio Rich Man's Revolt (Season 4, Episode 1): Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

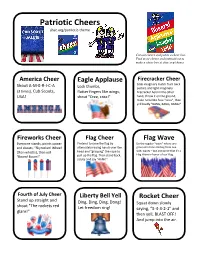

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Coloring Their World: Americans and Decorative Color in the Nineteenth Century

Coloring Their World: Americans and Decorative Color in the Nineteenth Century A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences by Kelly F. Wright B.A. College of William and Mary 1985 M.A. University of Cincinnati 2001 Committee Chair: Wayne K. Durrill, Ph.D. i ABSTRACT Certain events in recent history have called into question some long-held assumptions about the colors of our material history. The controversy over the cleaning of the Sistine Chapel posited questions about color to an international audience, and in the United States the restoration of original decorative colors at the homes of many historically significant figures and religious groups has elicited a visceral reaction suggesting the new colors challenge Americans’ entrenched notions of what constituted respectable taste, if not comportment, in their forebears. Recent studies have even demonstrated that something as seemingly objective as photography has greatly misled us about the appearance of our past. We tend to see the nineteenth century as a faded, sepia-toned monochrome. But nothing could be further from the truth. Coloring Their World: Americans and Decorative Color in the Nineteenth Century, argues that in that century we can witness one of the only true democratizations in American history—the diffusion of color throughout every level of society. In the eighteenth century American aristocrats brandished color like a weapon, carefully crafting the material world around them as a critical part of their political and social identities, cognizant of the power afforded them by color’s correct use, and the consequences of failure. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

Southridge High School and the Community Both in and out of Uniform

SSOOUUTTHHRRIIDDGGEE CCHHEEEERR TRYOUT APPLICATION SSC—You and Me! Southridge Cheer 2017 Family. Fun. Pride. Spirit. Stunt. Tumble. Compete. For more information, contact Liz Stiles, coach, via email: [email protected] 1 Southridge Cheer Team Information Team Philosophy Support Southridge athletic teams, events, etc. o Boost school spirit, promote good sportsmanship, develop good, positive crowd involvement and help student participants and spectators enjoy and maximize the spirit of the athletic events. Represent Southridge and the student body in an exemplary manner. o Be amongst the most visible and recognizable representatives of the school. The squad is in the position to greatly influence the school’s image as well as that of school pride and involvement; therefore, high standards of conduct and appearance are essential. Promote positive socialization and team cohesiveness. o Practice and promote a cooperative spirit among members of the team to create positive memories of high school life as well as enhancing the cooperative spirit in our school community and community at large. You are REQUIRED to bond and work with ALL team members. You WILL refrain from negativity within and about the team. Performance of cheers and routines is an essential role. o Members will work to achieve effective execution of cheers and routines as they play a key part in rallying the crowd and showcasing the squad’s abilities. To this end, all spirit squad members are considered athletes and are expected to condition and train in a manner befitting a strong, motivated and proud athletic team. Cheer Team Structure The Head Coach and Assistant Coach work together to make all decisions. -

Leader Board STANDINGS 2016 Leaderboard P Gross Skins # P Net

Leader Board STANDINGS 2016 Top 14 of Leader Board qualified for the Barney Cup vs Elmridge Top 5 in Gross and Net skins qualified for Season Ending Skins LeaderBoard P Gross Skins # P Net Skins # P 1 Jim Chiaradio 1418 Austin Cilley 27 480 Jim Chiaradio 11 306 2 Austin Cilley 1232 Jim Chiaradio 19 425 Lou Laudone 7 227 3 Chuck Falcone 1032 Karl Saila 17 273 Pete DiMaggio 11 223 4 Andy MacMahon 898 Andy McMahon 14 260 Chris Jurgasik 9 189 5 Chris Jurgasik 828 Glen Blackburn 11 235 Joe Luzzi Sr. 4 182 6 Tony Chiaradio 791 Chuck Falcone 8 192 Duke Ellington 7 179 7 Jim Murano 758 Mike Bliven 7 191 Ron Nye 7 179 8 Joe Luzzi Sr. 705 Jody Vacca 7 174 Chuck Falcone 7 175 9 John Donohue 692 Lou Laudone 8 156 Pete Chiaradio 7 171 10 Pete Chiaradio 676 John Donohue 11 154 Dave Morrone 7 168 11 Lou Laudone 653 Jack Donohue 4 132 Randy Dwight 4 165 12 Steve Ruzzo 621 Kyle James 7 102 Joe Woycik 6 161 13 Bob Gebler 613 Pete Chiaradio 5 95 Tom Hogan 6 152 14 Dave Morrone 608 Ray Barry 6 92 Randy Orlomoski 5 150 15 Mike Bliven 551 Joe Woycik 6 83 Bill Mathurin 5 127 16 Karl Saila 453 Jim Burbine 6 74 Mike Bliven 6 120 17 Joe Woycik 441 Joe Luzzi Sr. 4 63 Bob Gebler 5 119 18 Tom Hogan 436 Bob Gebler 4 59 Ed Morenzoni SR 3 116 19 Glen Blackburn 411 Lou Toscano 4 59 Vin Urso 2 115 20 Jim Burbine 405 Chris Jurgasik 5 57 Leo Larviere 4 110 21 Duke Ellington 377 John Doherty 1 45 Mike Classey 5 102 22 Lou Toscano 370 Bill Mathurin 2 43 Tony Chiaradio 4 100 23 Bill Mathurin 365 Charlie Toscano 2 28 John Sullivan 4 90 24 Jody Vacca 356 Randy Orlomoski 2 27 Charlie Toscano 4 88 25 John Sullivan 330 Joe Celico 2 25 Jack Donohue 2 82 26 Jack Donohue 324 Pete DiMaggio 2 24 Dave Crawn 3 75 27 Kyle James 322 Duke Ellington 1 18 Joe Luzzi Jr. -

Edmond / Norman 507 S

! EDMOND / NORMAN 507 S. Coltrane / 3203 Broce Dr. 341-2390 / 701-5999 www.CheersandMore.com Welcome to the Cheers and More All Star Cheerleading family. We are very proud of our highly successful, internationally recognized All Star Cheerleading program. This packet will provide you with the information you will need as parents of a Cheers and More All Star cheerleader. Please carefully read ALL of the important information contained in this packet. All Star Cheerleading is a serious and highly athletic team sport. The more you know, the better experience you and your child will have in this wonderful program. Cheers and More strives to insure that your child has every opportunity to learn cheerleading, achieve their goals, and have a great time, all while learning many important life lessons along the way. Many of the athletes we have trained have received college scholarships to continue cheering after high school. We rely on our All Star parents to help us build and maintain our family friendly, athlete centered atmosphere. All Star Squads Cheers and More All Stars are competitive cheerleaders participating in a serious team sport. Parental support of your children and his/her teams are an integral component to their success. We firmly believe that every athlete is a valuable and unique member of our program. Each child has a specific and unique contribution to his/her team that cannot be replaced. Our goal is to provide individual skill development for every child, not only in cheerleading, but in sportsmanship and teamwork as well. We will prepare our teams and athletes to perform to their individual and team best. -

Parent Communication Brochure

THE NEXT STEP IMPORTANT FACTS TO KEEP What can a parent do if the meeting with the IN MIND Vancouver coach did not provide a satisfactory resolution? 1. If an athlete visits a physician for an injury, he/she must bring a note from 1. Call and set-up an appointment the doctor before being allowed to School District with the athletic director to discuss return to practice. the situation. 2. Students who miss more than half a 2. At this meeting the appropriate day of classes are not eligible to par- next step can be determined as ticipate in that day’s practice or con- necessary. tests. Truancy will result in a suspen- ATHLETICS sion from the next scheduled contest. Whether or not this step is ever reached, please 3. Use of tobacco, drugs, or alcohol keep in mind the following protocol when you during the school year is a violation of elect to pursue a concern you have regarding Athletic Handbook rules and will result your son/daughter’s experience in one of our in an athletic suspension. Violations athletic programs. Please make contact as include actual use, possession and/or follows: sale, and con-structive possession as defined in the Athletic Handbook. 1. Head coach 4. Any athlete who is ejected from a 2. Athletic director contest will be suspended until after 3. Building principal the next contest at the same level is 4. District athletic coordinator completed. 5. Chief of secondary education 5. Athletes will be expected to maintain passing grades in 4 out of 5, 5 out of 6, Research indicates a student involved in co- or 6 out of 7 classes to be eligible to PARENT / COACH curricular activities has a greater chance for compete in contests. -

British and Colonial Naturalists Respond to an Enlightenment Creed, 1727–1777

“So Many Things for His Profit and for His Pleasure”: British and Colonial Naturalists Respond to an Enlightenment Creed, 1727–1777 N MAY OF 1773 the Pennsylvania farmer and naturalist John Bartram (1699–1777) wrote to the son of his old colleague Peter Collinson I(1694–1768), the London-based merchant, botanist, and seed trader who had passed away nearly five years earlier, to communicate his worry over the “extirpation of the native inhabitants” living within American forests.1 Michael Collinson returned Bartram’s letter in July of that same year and was stirred by the “striking and curious” observations made by his deceased father’s friend and trusted natural historian from across the Atlantic. The relative threat to humanity posed by the extinction of species generally remained an unresolved issue in the minds of most eighteenth-century naturalists, but the younger Collinson was evidently troubled by the force of Bartram’s remarks. Your comments “carry Conviction along with them,” he wrote, “and indeed I cannot help thinking but that in the period you mention notwithstanding the amazing Recesses your prodigious Continent affords many of the present Species will become extinct.” Both Bartram and Collinson were anxious about certain changes to the environment engendered by more than a century of vigorous Atlantic trade in the colonies’ indigenous flora and fauna. Collinson 1 The terms botanist and naturalist carry different connotations, but are generally used interchange- ably here. Botanists were essentially those men that used Linnaeus’s classification to characterize plant life. They were part of the growing cadre of professional scientists in the eighteenth century who endeavored to efface irrational forms of natural knowledge, i.e., those grounded in folk traditions rather than empirical data. -

TITLE Stella Mccartney: Responsibility's on the Agenda

TITLE Stella McCartney: responsibility's on the agenda INTRO She is one of the most successful fashion designers of our time and the woman behind the world's first vegetarian luxury fashion brand. But the road to the top has been tough. Stella McCartney talks to Anna Blom about panic attacks and the 'rich daddy's girl' label, and her own hard slog to get the fashion industry to become sustainable and modern. COPY How can you become one of the world's most successful fashion designers without using real leather? Stella McCartney, founder of the fashion house of the same name and daughter of ex-Beatle Sir Paul McCartney, has done just that. Famous for her feminine silhouettes and masculine-inspired garments, her fashion emporium is worth billions. Her 'Falabella' bag from 2010 is an icon, despite the fact that it is made using 'eco alter nappa', a mixture of recycled polyester and vegetable oils. Ever since her graduation show from Central Saint Martins in London in 1995, she has refused to use real leather, furs or feathers. She has been vegetarian since childhood, and when she was growing up her father Paul used to challenge her and her siblings to come up with an alternative to meat for the family's dinner. Her late mother Linda McCartney even launched a successful series of frozen vegetarian food in the UK, long before today's veggie trend. This consideration for people, animals and nature has followed Stella McCartney throughout her life. "For me, vegetarianism is based on ethics. My mum was very vocal and we were all educated to understand why we weren't eating meat. -

MIDWEEK RESULTS - Skins Game

MIDWEEK RESULTS - Skins game. December '14 Team #1 $ Team #2 $ Massingill, Harry D $48 Bradley, Gary $30 Espinosa, William $30 Rodriguez, Jose M $12 Ashen, Chuck H $30 Fairhurst, Neil B $24 Rodriguez, Don 0 Ahders, Bob $42 8:00 AM 8:08 AM Team #3 $ Team #4 $ Yurong, Willam $25.50 Deacon, Peter $90 Spreitzer, Gene $13.50 Guinn, Gary 0 Hart, Jeff $55.50 Kemp, Vern $12 Berg, Don $13.50 Siler, Roger R $6 Time: 08:16 am Time: 08:24 am Team #5 $ Team #6 $ Dopkins, Steve C 0 Hodges, Gary R $6 Jones, Chris David $72 Whitaker, Bill $24 Nygard, Kevin L $18 Chase, Jerry M $60 Watts, David A $18 McIntyre, Stuart $18 Time: 08:32 am Time: 08:40 am Team #7 $ Team #8 $ Reid, Robert A $48 Bottel, Rod $48 Auble, James $36 Reed, Alan E $30 Hoffman, Ms. Jan $12 Chow, Weldon $0 Gauthreaux, Sidney J $12 Baynes, Keith C. $30 Time: 08:48 am Time: 08:56 am Team #9 $ Team #10 $ Rousseve, Greg $9 Stein, Greg $36 Pintar, Donn $45 Bradford, Jeff 0 Landis, Steven $15 Smiley, George $18 Clark, Andrew J $39 Welborn, Roger $54 Time: 09:04 am Time: 09:12 am Team #11 $ Team #12 $ Kaczor, John D $6 Currier, Edwin J $6 Steyn, Gerard $60 Deccico, Jim $21 Henry, Ken W $24 Fleischer, Rich $63 Landsittel, Donald $18 Dixon, Robert $18 Time: 09:20 am Time: 09:28 am Team #13 $ Tee Team #14 $ Seymour, Ralph V $12 Dileo, Marty 0 Myas, Brandt R. $18 Jurach, Jerry P $30 Vona, Joe $30 Oneil, Dennis $36 Fasciola, Joe $48 Humphrey, Jack $42 Time: 09:36 am Time: 09:44 am Team #15 $ Team #16 $ Steed, Don $36 Beach, George W $9 Foster, Randy $30 Olson, Doug $21 1 MIDWEEK RESULTS - Skins game.