Habitat Restoration for Lupine and Specialist Butterflies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A SKELETON CHECKLIST of the BUTTERFLIES of the UNITED STATES and CANADA Preparatory to Publication of the Catalogue Jonathan P

A SKELETON CHECKLIST OF THE BUTTERFLIES OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA Preparatory to publication of the Catalogue © Jonathan P. Pelham August 2006 Superfamily HESPERIOIDEA Latreille, 1809 Family Hesperiidae Latreille, 1809 Subfamily Eudaminae Mabille, 1877 PHOCIDES Hübner, [1819] = Erycides Hübner, [1819] = Dysenius Scudder, 1872 *1. Phocides pigmalion (Cramer, 1779) = tenuistriga Mabille & Boullet, 1912 a. Phocides pigmalion okeechobee (Worthington, 1881) 2. Phocides belus (Godman and Salvin, 1890) *3. Phocides polybius (Fabricius, 1793) =‡palemon (Cramer, 1777) Homonym = cruentus Hübner, [1819] = palaemonides Röber, 1925 = ab. ‡"gunderi" R. C. Williams & Bell, 1931 a. Phocides polybius lilea (Reakirt, [1867]) = albicilla (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) = socius (Butler & Druce, 1872) =‡cruentus (Scudder, 1872) Homonym = sanguinea (Scudder, 1872) = imbreus (Plötz, 1879) = spurius (Mabille, 1880) = decolor (Mabille, 1880) = albiciliata Röber, 1925 PROTEIDES Hübner, [1819] = Dicranaspis Mabille, [1879] 4. Proteides mercurius (Fabricius, 1787) a. Proteides mercurius mercurius (Fabricius, 1787) =‡idas (Cramer, 1779) Homonym b. Proteides mercurius sanantonio (Lucas, 1857) EPARGYREUS Hübner, [1819] = Eridamus Burmeister, 1875 5. Epargyreus zestos (Geyer, 1832) a. Epargyreus zestos zestos (Geyer, 1832) = oberon (Worthington, 1881) = arsaces Mabille, 1903 6. Epargyreus clarus (Cramer, 1775) a. Epargyreus clarus clarus (Cramer, 1775) =‡tityrus (Fabricius, 1775) Homonym = argentosus Hayward, 1933 = argenteola (Matsumura, 1940) = ab. ‡"obliteratus" -

Book Review, of Systematics of Western North American Butterflies

(NEW Dec. 3, PAPILIO SERIES) ~19 2008 CORRECTIONS/REVIEWS OF 58 NORTH AMERICAN BUTTERFLY BOOKS Dr. James A. Scott, 60 Estes Street, Lakewood, Colorado 80226-1254 Abstract. Corrections are given for 58 North American butterfly books. Most of these books are recent. Misidentified figures mostly of adults, erroneous hostplants, and other mistakes are corrected in each book. Suggestions are made to improve future butterfly books. Identifications of figured specimens in Holland's 1931 & 1898 Butterfly Book & 1915 Butterfly Guide are corrected, and their type status clarified, and corrections are made to F. M. Brown's series of papers on Edwards; types (many figured by Holland), because some of Holland's 75 lectotype designations override lectotype specimens that were designated later, and several dozen Holland lectotype designations are added to the J. Pelham Catalogue. Type locality designations are corrected/defined here (some made by Brown, most by others), for numerous names: aenus, artonis, balder, bremnerii, brettoides, brucei (Oeneis), caespitatis, cahmus, callina, carus, colon, colorado, coolinensis, comus, conquista, dacotah, damei, dumeti, edwardsii (Oarisma), elada, epixanthe, eunus, fulvia, furcae, garita, hermodur, kootenai, lagus, mejicanus, mormo, mormonia, nilus, nympha, oreas, oslari, philetas, phylace, pratincola, rhena, saga, scudderi, simius, taxiles, uhleri. Five first reviser actions are made (albihalos=austinorum, davenporti=pratti, latalinea=subaridum, maritima=texana [Cercyonis], ricei=calneva). The name c-argenteum is designated nomen oblitum, faunus a nomen protectum. Three taxa are demonstrated to be invalid nomina nuda (blackmorei, sulfuris, svilhae), and another nomen nudum ( damei) is added to catalogues as a "schizophrenic taxon" in order to preserve stability. Problems caused by old scientific names and the time wasted on them are discussed. -

(Callophrys Irus Hadros). B

1. Cover Page a. Title: Range, population size, and habitat utilization of the Texas frosted elfin (Callophrys irus hadros). b. Project Summary: The goal of this proposal is to determine the status and habitat utilization of Callophrys irus hadros (Texas frosted elfin). This Lepidoptera species has been recorded only a few times in Arkansas and occupies habitats that have been severely impacted by human activity. It has not been studied in detail in Arkansas. Callophrys irus hadros is the only Lepidoptera listed on the 2017 State Wildlife Grant Funding Priorities (SWGFP) and has been petitioned for listing by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Endangered Species Act. It is associated with prairies, grassland, and open woodland habitats, which are high priority for habitats under the 2017 SWGFP. Once the range, population size, and habitat utilization of this species is more fully understood, conservation recommendations will be developed to improve the chances of survival of this presumed rare component of Arkansas biodiversity and contribute to actions that may preclude the need to list the species. c. Project Leaders: Matthew D. Moran. Professor of Biology, Hendrix College. 1600 Washington Ave. Conway, AR 72032. Phone: 501-450-3814. Email: [email protected] Project Activities: He will participate in field and laboratory work and help coordinate student field workers. Maureen McClung. Assistant Professor of Biology, Hendrix College. 1600 Washington Ave. Conway, AR 72032. Phone: 501-450-1486. Email: [email protected] Project Activities: She will participate in field and laboratory work and help coordinate student field workers. d. Project Partners: Melissa Lombardi, Endangered Species Biologist, U.S. -

Larval Feeding Behavior and Ant Association In

J OURNAL OF T HE L EPIDOPTERISTS’ S OCIETY Volume 61 2007 Number 2 Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 61(2), 2007, 61–66 LARVAL FEEDING BEHAVIOR AND ANT ASSOCIATION IN FROSTED ELFIN, CALLOPHRYS IRUS (LYCAENIDAE) GENE ALBANESE Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management, 404 LSW, Fish & Wildlife Unit, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078-3051, USA, e-mail: [email protected] MICHAEL W. N ELSON Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough, MA 01581, USA, e-mail: [email protected] PETER D. VICKERY Center for Ecological Research, P.O. Box 127, Richmond, ME 04357, USA, email: [email protected] AND PAUL R. SIEVERT U. S. Geological Survey, Massachusetts Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Department of Natural Resources Conservation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA 01003, USA, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Callophrys irus is a rare and declining lycaenid found in the eastern U.S., inhabiting xeric and open habitats maintained by disturbance. Populations are localized and monophagous. We document a previously undescribed larval feeding behavior in both field and lab reared larvae in which late instar larvae girdled the main stem of the host plant. Girdled stems provide a unique feeding sign that was useful in detecting the presence of larvae in the field. We also observed frequent association of field larvae with several species of ants and provide a list of ant species. We suggest two hypotheses on the potential benefits of stem-girdling to C. irus larvae: 1) Stem girdling provides phloem sap as a larval food source and increases the leaf nutrient concen- tration, increasing larval growth rates and providing high quality honeydew for attending ants; 2) Stem girdling reduces stem toxicity by inhibiting transport of toxins from roots to the stem. -

Our Home and Native Land: Canadian Species of Global Conservation Concern

Our Home and Native Land Canadian Species of Global Conservation Concern NatureServe Canada contributes to the conservation of Canada’s biodiversity by providing scientific data and expertise about species and ecosystems of conservation concern to support decision-making, research, and education. Citation: Cannings, S., M. Anions, R. Rainer, and B. Stein. 2005. Our Home and Native Land: Canadian Species of Global Conservation Concern. NatureServe Canada: Ottawa, Ontario. © NatureServe Canada 2005 ISBN 0-9711053-4-0 Primary funding for the publication of this report was provided by the Suncor Energy Foundation. This report is also available in French. To request a copy, please contact NatureServe Canada. NatureServe Canada 960 Carling Avenue Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 613-759-1861 www.natureserve-canada.ca Our Home and Native Land Canadian Species of Global Conservation Concern by Sydney Cannings Marilyn F. E. Anions Rob Rainer Bruce A. Stein Sydney Cannings NatureServe Yukon Fish and Wildlife Branch Yukon Department of the Environment P.O. Box 2703 Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6 867-667-3684 Marilyn F. E. Anions NatureServe Canada 960 Carling Avenue Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 Note on Captions: For each species, captions state the range in Canada only, as well as the NatureServe global conservation status. 613-759-1942 Rob Rainer Front Cover Chelsea, Québec Left to right: Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus). Vulnerable (G3). 819-827-9082 British Columbia. / Photo by Jared Hobbs. Golden paintbrush (Castilleja levisecta). Critically imperiled (G1). British Bruce A. Stein, Ph.D. Columbia. / Photo by Leah Ramsay, British Columbia Conservation Data NatureServe Centre. 1101 Wilson Blvd., 15th Floor Spotted owl (Strix occidentalis). -

COSEWIC Status Appraisal Summary on the Frosted Elfin Callophrys Irus in Canada

COSEWIC Status Appraisal Summary on the Frosted Elfin Callophrys irus in Canada EXTIRPATED 2010 COSEWIC status appraisal summaries are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk in Canada. This document may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2010. COSEWIC status appraisal summary on the Frosted Elfin Callophrys irus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: This status appraisal summary constitutes a review of classification of the Frosted Elfin Callophrys irus in Canada which was last assessed by COSEWIC in 2000. The 2000 COSEWIC Status Report on the Frosted Elfin Callophrys irus in Canada is posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry at this link: http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=590 COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Ross A. Layberry for writing the status appraisal summary on the Frosted Elfin Callophrys irus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This status appraisal summary was overseen and edited by Laurence Packer, Co-chair of the Arthropods Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Sommaire du statut de l’espèce du COSEPAC sur le Lutin givré (Callophrys irus) au Canada. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2010. Catalogue No. CW69-14/2-5-2010E-PDF ISBN: 978-1-100-16635-3 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2010 Common name Frosted Elfin Scientific name Callophrys irus Status Extirpated Reason for designation * A reason for designation is not specified when a review of classification is conducted by means of a status appraisal summary. -

Frosted Elfin Fact Sheet SC 2017.Pub

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service September 2017 Conserving South Carolina’s At-Risk Species: www.fws.gov/charleston www.fws.gov/southeast/candidateconservation Species facing threats to their survival Frosted elfin southern New England south to coastal teria employed in a biological insecticide (Callophrys irus) areas of North and South Caroli- used to eradicate the gypsy moth) poses a na; Callophrys irus hadra is confined to east serious hazard to frosted elfin larvae. Texas and west Arkansas. In South Caro- lina, the species is known from the follow- Management/Protection Needs ing counties: Aiken, Berkeley, Charles- Populations are often small and local and ton, Chesterfield, and Georgetown. generally need conservation attention. As with many butterflies, protection and Habitat management of their habitat to ensure the Frosted elfins require open woods, forest presence of hostplant populations is the edges, fields, and scrub in which their lar- primary need. Due to the successional val hostplants grow. Increasingly, it is nature of the habitat, appropriate vegeta- confined to disturbed patches such as tion management is important as poor powerline rights of way and along rail- actions such as overgrazing or badly timed roads and not purely natural habitat. Rec- prescribed fire may negatively impact the orded hostplants are all in the pea family butterflies. Gypsy moth suppression pro- Frosted elfin/Will Cook (Fabaceae). Wild indigo (Baptisia tinctoria) grams must consider the impacts on frost- and wild (sundial) lupine (Lupinus perennis) ed elfin populations. Surveys for uniden- Description are most frequently used. The subspecies tified populations in all states where it is The frosted elfin is in the family Lycaeni- vary in their hostplant preferences. -

Twenty Years of Elfin Enumeration: Abundance Patterns of Five Species of Callophrys (Lycaenidae) in Central Wisconsin, USA

Insects 2014, 5, 332-350; doi:10.3390/insects5020332 OPEN ACCESS insects ISSN 2075-4450 www.mdpi.com/journal/insects/ Article Twenty Years of Elfin Enumeration: Abundance Patterns of Five Species of Callophrys (Lycaenidae) in Central Wisconsin, USA Ann B. Swengel * and Scott R. Swengel 909 Birch Street, Baraboo, WI 53913, USA * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-608-356-9543. Received: 24 February 2014; in revised form: 14 April 2014 / Accepted: 15 April 2014 / Published: 23 April 2014 Abstract: We recorded five species of elfins (Callophrys) during annual spring surveys targeting frosted elfin C. irus (state-listed as threatened) in 19 pine-oak barrens in central Wisconsin USA during 1994–2013. At the northwest end of its range here, C. irus co-varied with spring temperature, but declined significantly over time (eight sites verified extant of originally 17). Two other specialists increased significantly. The northern specialist, hoary elfin C. polios (nine sites), correlated positively with the previous year’s growing season precipitation. The southern specialist, Henry’s elfin C. henrici (11 sites), co-varied with winter precipitation and spring temperature and dryness. The two resident generalists had stable trends. For all species, the first observed date per year became earlier over time and varied more than the last observed date. Thus, flight period span increased with earlier first observed dates. Elfin abundance increased significantly with earlier first observed dates in the current and/or prior year. Three species (C. irus, C. henrici, a generalist) had more positive population trends in reserves than non-reserves. -

(Lycaenidae) Two Genetically Distinct Host Plant Races in Maryland? DNA Evidence from Cast Larval Skins Provides an Answer

Is the globally rare frosted elfin butterfly (Lycaenidae) two genetically distinct host plant races in Maryland? DNA evidence from cast larval skins provides an answer Jennifer A. Frye & Robert K. Robbins Journal of Insect Conservation An international journal devoted to the conservation of insects and related invertebrates ISSN 1366-638X Volume 19 Number 4 J Insect Conserv (2015) 19:607-615 DOI 10.1007/s10841-015-9783-4 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer International Publishing Switzerland (outside the USA) . This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self-archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy J Insect Conserv (2015) 19:607–615 DOI 10.1007/s10841-015-9783-4 ORIGINAL PAPER Is the globally rare frosted elfin butterfly (Lycaenidae) two genetically distinct host plant races in Maryland? DNA evidence from cast larval skins provides an answer 1 2 Jennifer A. Frye • Robert K. Robbins Received: 12 January 2015 / Accepted: 4 June 2015 / Published online: 23 June 2015 Ó Springer International Publishing Switzerland (outside the USA) 2015 Abstract Frosted elfin butterfly caterpillars (Callophrys base pair sequence. -

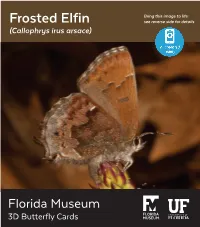

Frosted Elfin See Reverse Side for Details (Callophrys Irus Arsace)

Bring this image to life: Frosted Elfin see reverse side for details (Callophrys irus arsace) Florida Museum 3D Butterfly Cards Inspiring people to care about life on earth The Frosted Elfin (Callophrys irus arsace) is a small, primarily brown hairstreak butterfly. It is widespread across the eastern half of the United States from the Northeast and Great Lakes south to Florida and west to eastern Texas. However, it is rare and in decline in most areas. In fact, the Frosted Elfin is listed as endangered, threatened or of conservation concern in 11 states and has been lost entirely from Canada. It reaches its southernmost distribution in northern Florida where only a handful of small remaining populations are known to occur. The Frosted Elfin occurs in regularly disturbed habitats such as oak-pine barrens, oak savannahs and upland pine or sandhill where its larval host plants, Wild Indigo (Baptisia tinctoria) and Wild Lupine (Lupinus perennis), grow. These habitats have dwindled significantly due to land development and degradation of vegetation because of succession and fragmentation, resulting in continued declines of the butterfly. Fire, both natural and prescribed, is the major source of disturbance in these systems and is critical for maintaining optimal habitat quality. But fire also can be potentially harmful to small populations if improperly applied. Research at the University of Florida shows that fire management for the Frosted Elfin should only occur in a portion of a species occupied area, be rotated between years and be a fast moving fire to limit mortality. • Download the Libraries of Life app from the iTunes or Android store and install on your device. -

Frosted Elfin Callophrys Iris

Appendix A: Insects Frosted Elfin Callophrys iris Federal Listing N/A State Listing E Global Rank State Rank S1 Regional Status Photo by NHFG Justification (Reason for Concern in NH) The frosted elfin, along with the Karner blue butterfly, is an indicator of the health of the pine barrens habitat. As habitat goes unmanaged and reverts to a closed canopy system, the frosted elfin will die out. Frosted elfins are highly susceptible to population declines, which are a product of host plant specificity, environmental change, low dispersal rates, and small subpopulation size (Cushman and Murphy 1993), as well as cannibalism among larva. These factors are magnified by a severe loss of habitat. Nearly 90% of historic pine barrens communities along the Merrimack River have been lost, leaving a mere 560 fragmented acres, primarily in Concord (Helmbolt and Amaral 1994). Distribution The range of the frosted elfin extends from northern New England across to New York, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin, and along the eastern seaboard with pockets in southern New Jersey, eastern Maryland, West Virginia, South Carolina, and northern Florida (Swengel 1986, Schwitzer 1992, NatureServe 2005). The frosted elfin is believed to have been extirpated in Ontario, Maine, and Illinois (NatureServe 2015). In New Hampshire, populations of the frosted elfin currently occur only in the Concord Pine Barrens, but there are records from the towns of Webster and Durham from the early 1900s, indicating that these areas once supported frosted elfin habitat (New Hampshire Natural Heritage Bureau 2015). Habitat The habitat of the frosted elfin in New Hampshire is identical to that of the federally endangered Karner blue butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis): pine barrens with ample patches of blue lupine (Lupinus perennis), the only larval host plant (Schweitzer 1992, Swengel 1996). -

Updated List of the Butterflies and Skippers of Florida (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea and Hesperioidea)

Vol. 4 No. 2 1997 CALHOUN: Florida Butterfly List 39 HOLARCTIC LEPIDOPTERA, 4(2): 39-50 UPDATED LIST OF THE BUTTERFLIES AND SKIPPERS OF FLORIDA (LEPIDOPTERA: PAPILIONOIDEA AND HESPERIOIDEA) JOHN V. CALHOUN1 977 Wicks Dr., Palm Harbor, Florida 34684, USA ABSTRACT.- An updated list of the butterflies and skippers of Florida is presented which treats 193 species (211 species and subspecies). English common names are provided. Type localities are given for species and subspecies described from Florida material. Also included are synonymous and infrasubspecific taxa that possess Florida type localities. The status (resident, naturalized resident, immigrant, accidental introduction, stray, or status unknown) and general geographic range (west, north, central, and south) of each species and subspecies in Florida are indicated. Endemic, as well as rare and imperiled taxa are recognized. Erroneous records are noted in an Appendix. KEY WORDS: Caribbean, classification, Florida Keys, Hesperiidae, history, Lycaenidae, Nearctic, nomenclature, North America, Nymphalidae, Papilionidae, Pieridae, Riodinidae, taxonomy, USA, West Indies. Since the pioneer botanist, William Bartram (1791), reported expeditions, sponsored by the American Museum of Natural finding "multitudinous" butterflies visiting flowers near the banks History, were conducted in Florida in 1911, 1912, and 1914. The of the Indian River along the east coast of Florida in December results of these expeditions contributed to the first published list 1774, numerous entomologists and naturalists have combed of all known species of Florida Lepidoptera. Originally compiled Florida's landscape with hopes of encountering interesting and by John A. Grossbeck and expanded by Frank E. Watson after unknown species of Lepidoptera. Early explorers included Grossbeck's untimely death in 1914, this list included 160 species Bartram's grandnephew, the venerable Thomas Say ("The Father of butterflies and skippers (Grossbeck, 1917).