Twenty Years of Elfin Enumeration: Abundance Patterns of Five Species of Callophrys (Lycaenidae) in Central Wisconsin, USA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incisalia Fotis Schryveri (Lycaenidae): Bionomic Notes and Life History

256 JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTEHISTS' SOCIETY INCISALIA FOTIS SCHRYVERI (LYCAENIDAE): BIONOMIC NOTES AND LIFE HISTORY CLIFFORD D. FERRIS University of Wyoming, Laramie and RAY E. STANFORD Denver, Colorado In the years that have elapsed since the original description of Incisalia fotis schryveri Cross (1937), little additional information has been gath ered regarding the biology of the insect. The distributional limits have been imprecisely determined, the immature stages have remained un described, and only vague speculation has appeared regarding possible host plants. This paper constitutes the first description of the immature stages and a record of the host plant. The insect was studied in Wyoming (by Ferris) and in Colorado (by Stanford). In the paragraphs which follow, where regional differences exist, state names will bc mentioned; otherwise descriptions pertain to the entire range of schryveri. Ecology and Nature of Habitat Incisalia fotis schryveri occurs in multiplc colonies in the eastern foot hills of the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains in north-central Colo rado, and in the continuation of this range into south-eastern Wyoming. Its northern limits, or possible blend zones with I. fotis mossii (H. Edwards), have yet to be determined, but in Colorado it seems to ex tend no farther south than El Paso Co. Rccords are also available from Boulder, Clcar Creek, Douglas, Gilpin, and Larimer Cos. The species probably occurs also in thc northeast portion of Park Co., along the Platte River, and may be found in parts of Teller Co. In Wyoming, it is known from Albany, Carbon, and Converse Cos., and is associated with the Laramie, North Platte, and Platte Hiver drainages. -

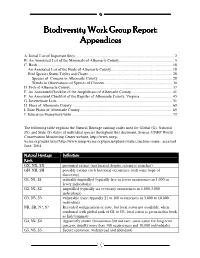

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices A: Initial List of Important Sites..................................................................................................... 2 B: An Annotated List of the Mammals of Albemarle County........................................................ 5 C: Birds ......................................................................................................................................... 18 An Annotated List of the Birds of Albemarle County.............................................................. 18 Bird Species Status Tables and Charts...................................................................................... 28 Species of Concern in Albemarle County............................................................................ 28 Trends in Observations of Species of Concern..................................................................... 30 D. Fish of Albemarle County........................................................................................................ 37 E. An Annotated Checklist of the Amphibians of Albemarle County.......................................... 41 F. An Annotated Checklist of the Reptiles of Albemarle County, Virginia................................. 45 G. Invertebrate Lists...................................................................................................................... 51 H. Flora of Albemarle County ...................................................................................................... 69 I. Rare -

Callophrys Gryneus (Juniper Hairstreak)

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Callophrys gryneus (Juniper Hairstreak) Priority 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Insecta (Insects) Order: Lepidoptera (Butterflies, Skippers, And Moths) Family: Lycaenidae (Gossamer-winged Butterflies) General comments: Only 2-3 populations – previously historic; specialized host plant; declining and vulnerable habitat. Species Conservation Range Maps for Juniper Hairstreak: Town Map: Callophrys gryneus_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Callophrys gryneus_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: Maine Status: Endangered State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: NA High Climate Change Vulnerability: NA Understudied rare taxa: Recently documented or poorly surveyed rare species for which risk of extirpation is potentially high (e.g. few known occurrences) but insufficient data exist to conclusively assess distribution and status. *criteria only qualifies for Priority 3 level SGCN* Notes: Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to Juniper Hairstreak: Formation Name Cliff & Rock Macrogroup Name Cliff and Talus Habitat System Name: North-Central Appalachian Acidic Cliff and Talus **Primary Habitat** Notes: where host plant (red cedar) present Habitat System Name: North-Central Appalachian Circumneutral Cliff and Talus Notes: where host plant (red cedar) present Formation Name Grassland & Shrubland Macrogroup -

Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis Persius Persius

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada ENDANGERED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 41 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge M.L. Holder for writing the status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. COSEWIC also gratefully acknowledges the financial support of Environment Canada. The COSEWIC report review was overseen and edited by Theresa B. Fowler, Co-chair, COSEWIC Arthropods Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’Hespérie Persius de l’Est (Erynnis persius persius) au Canada. Cover illustration: Eastern Persius Duskywing — Original drawing by Andrea Kingsley ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2006 Catalogue No. CW69-14/475-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43258-4 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name Eastern Persius Duskywing Scientific name Erynnis persius persius Status Endangered Reason for designation This lupine-feeding butterfly has been confirmed from only two sites in Canada. -

Butterfly Gardening Tips & Tricks Gardening for Butterflies Is Fun, Beautiful, and Good for the Environment

Butterfly Gardening Tips & Tricks Gardening for butterflies is fun, beautiful, and good for the environment. It is also simple and can be done in almost any location. The key guidelines are listed below: NO PESTICIDES! Caterpillars are highly susceptible to almost all pesticides so keep them away from your yard if you want butterflies to thrive. Select the right plants. You will need to provide nectar sources for adults and host plants for caterpillars. See the lists below for inspiration. Keep to native varieties as much as possible. Plants come in lots and lots of varieties and cultivars. When selecting plants, especially host plants, try to find native species as close to the natural or wild variety as possible. Provide shelter. Caterpillars need shelter from the sun and shelter from cold nights. Adults need places to roost during the night. And protected areas are needed for the chrysalis to safely undergo its transformation. The best way to provide shelter is with large clumps of tall grasses (native or ornamental) and medium to large evergreen trees and/or shrubs. Nectar Sources Top Ten Nectar Sources: Asclepias spp. (milkweed) Aster spp. Buddleia spp. (butterfly bush) Coreopsis spp. Echinacea spp. (coneflower) Eupatorium spp. (joe-pye weed) Lantana spp. Liatris spp. Pentas spp. Rudbeckia spp. (black-eyed susan) Others: Agastache spp. (hyssop), Apocynum spp. (dogbane), Ceanothus americanus (New Jersey tea), Cephalanthus occidentalis (button bush), Clethra alnifolia, Cuphea spp. (heather), Malus spp. (apple), Mentha spp. (mint), Phlox spp., Pycanthemum incanum (mountain mint), Salivs spp. (sage), Sedum spectabile (stonecrop), Stokesia laevis (cornflower), Taraxacum officinale (dandelion), Triofolium spp. -

Butterflies and Moths of San Bernardino County, California

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

Chapter17 Appendixiii Species List.Pub

Appendix 3: Species List English Latin French PLANTS Acadian quillwort Isoetes acadiensis Isoète acadien Alder Alnus sp. Aulne Alpine bilberry (bog blueberry) Vaccinium uliginosum Airelle des marécages Alternate-leaved dogwood Cornus alternifolia Cornouiller à feuilles alternes American mountain-ash Sorbus americana Sorbier d’Amérique (cormier) American red currant Ribes triste Gadellier amer Arctic sweet coltsfoot Petasites frigidus Pétasite palmé (pétasite hybride) Arrow-grass Triglochin sp. Troscart Ash Fraxinus sp. Frêne Aspen Populus sp. Tremble Atlantic manna grass Glyceria obtusa Glycérie Awlwort Subularia aquatica Subulaire aquatique Back’s sedge Carex backii Carex de Back Bake-apple (cloudberry) Rubus chamaemorus Ronce petit-mûrier (mûres blanches) Balsam fir Abies balsamea Sapin baumier Balsam poplar Populus balsamifera Peuplier baumier (liard) Basswood (American linden) Tilia americana Tilleul d’Amérique (bois blanc) Bathurst saltmarsh aster Aster subulatus var. obtusifolius Aster subulé Beaked hazelnut Corylus cornuta Noisetier à long bec Beech (American beech) Fagus grandifolia Hêtre à grandes feuilles (hêtre américain) Bigelow’s sedge Carex bigelowii Carex de Bigelow Birch Betula sp. Bouleau Black ash Fraxinus nigra Frêne noir Black cherry Prunus serotina Cerisier Tardif Black crowberry Empetrum nigrum Camarine noire (Graines à corbigeaux) Black grass Juncus gerardii Jonc de Gérard Black spruce Picea mariana Épinette noire Black willow Salix nigra Saule noir Bloodroot Sanguinaria canadensis Sanguinaire du Canada (sang-dragon) -

Spotting Butterflies Says Ulsh

New & Features “A butterfly’s lifespan generally cor- responds with the size of the butterfly,” Spotting Butterflies says Ulsh. The tiny blues often seen in the mountains generally only live about How, when and where to find Lepidoptera in 10 days. Some species, however, will the Cascades and Olympics overwinter in the egg, pupa or chrysalid form (in the cocoon prior to becoming winged adults). A few Northwest spe- cies overwinter as adults, and one—the mourning cloak—lives for ten months, and is the longest lived butterfly in North America. The first thing that butterflies do upon emerging from the chrysalis and unfold- ing their wings is to breed. In their search for mates, some butterflies “hilltop,” or stake out spots on high trees or ridgelines to make themselves more prominent. A butterfly’s wing colors serve two distinct purposes. The dorsal, or upperside of the wings, are colorful, and serve to attract mates. The ventral, or underside of the wings generally serves to camouflage the insects. So a butterfly such as the satyr comma has brilliant orange and yellow Western tiger and pale tiger swallowtail butterflies “puddling.” When looking for for spots when seen with wings open, and butterflies along the trail keep an eye on moist areas or meadows with flowers. a bark-like texture to confuse predators when its wings are closed. By Andrew Engelson Butterfly Association, about where, how As adults, butterflies also seek out Photos by Idie Ulsh and when to look for butterflies in our nectar and water. Butterflies generally mountains. Ulsh is an accomplished Butterflies are the teasers of wildlife. -

The Butterfly Drawings by John Abbot in the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia

VOLUME 61, NUMBER 3 125 Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 61(3), 2007, 125–137 THE BUTTERFLY DRAWINGS BY JOHN ABBOT IN THE HARGRETT RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA. JOHN V. C ALHOUN1 977 Wicks Dr., Palm Harbor, FL 34684 ABSTRACT. Artist-naturalist John Abbot completed 105 drawings of insects that are now deposited in the Hargrett Rare Book and Manu- script Library, University of Georgia. The provenance of these drawings is unknown, but available evidence dates them to ca. 1820–1825. The adults in the 32 butterfly drawings are identified and the figures of larvae and pupae are assessed for accuracy. The illustrated plants are also identified and their status as valid hosts is examined. Abbot’s accompanying notes are transcribed and analyzed. Erroneous figures of larvae, pupae, and hostplants are discussed using examples from the Hargrett Library. At least four of the butterfly species portrayed in the drawings were probably more widespread in eastern Georgia during Abbot’s lifetime. Additional key words: Larva, Lepidoptera, pupa, watercolors In 1776, the English artist-naturalist John Abbot METHODS (1751–ca.1840) arrived in Georgia, where he I visited the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript documented species of animals and plants for the next Library (University of Georgia) in April, 2005. Digital six decades. Living in Burke, Bullock, Chatham, and photographs were taken of John Abbot’s butterfly Screven Counties of eastern Georgia, he explored a drawings and their accompanying notes. The adult region roughly bound by the cities of Augusta and butterflies were identified and the figures compared Savannah, between the Oconee, Altamaha, and with those in other sets of Abbot’s drawings that are Savannah Rivers. -

The Linda Loring Nature Foundation Is an 86

#18 Bearberry, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi: This unique as well as form a stand or grove. This plant is uplands where the soil is mildly acidic. The bushes plant is a shrub that grows along the ground. You will important to a huge variety of insects and the grow tall and dense, keeping much of the fruit out of notice some woody stems nearby that are some of vertebrates that eat them. reach of all except birds and people. Generations of the branches of these very old plants. Also called hog Nantucketer’s have been known to keep secret the cranberry or mealy plum, the red fruit ripens in #22 Scrub Oak, Quercus ilicifolia: This plant is an locations of their prized blueberry bushes! Visitors’ Trail Guide autumn and while dry and tasteless to humans it was incredibly tough survivor. It is a shrubby tree that is formerly a favorite food of the large flocks of more knarly scrub than mighty oak. Yet it is perhaps #26 Japanese Black Pine, Pinus thunbergii: These The Linda Loring Nature Foundation is an 86- American golden plovers, Pluvialis dominica, found on mightier than the familiar mainland species as it is able pines, as their name implies, are native to Japan. Able acre preserve for conservation, education and Nantucket in the fall and the extinct Eskimo curlew, to survive in habitats where little else can. A deep tap to grow in very harsh conditions in impoverished Numenius borealis. Tiny pink flowers bloom in April or root resists tearing up by storms and helps the plant sandy soils and extremely salt tolerant, this fast research. -

Alaska LNG Environmental Impact Statement

APPENDIX P Special Status Species Lists APPENDIX P: Special Status Species Lists Table of Contents Table P-1 Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Sensitive and Watch List Species Associated with the Mainline Facilities ............................................................................................ P-1 Table P-2 Alaska Species of Greatest Conservation Need ............................................................ P-11 TABLE P-1 Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Sensitive and Watch List Species Associated with the Mainline Facilities Species a BLM Status Description Alaska Region b Habitat Birds Aleutian tern Sensitive Medium-sized tern; underparts are Restricted to coastal areas throughout the Breeding habitat includes vegetated (Onychoprion aleuticus) white, crown and mantle speckled white, Aleutian Islands, north to the southeastern islands, shrub-tundra, grass and and tail gray with white sides; Chukchi Sea and east to the Alaska Peninsula, sedge meadows, and freshwater differentiated from similar species by Yakutat, and Glacier Bay; most of the Alaska marshes; habitat during migration is dark bar on secondaries. population is concentrated in the Gulf of pelagic Alaska American golden plover Watch List Stocky, medium-sized shorebird with a Breeds through north and central Alaska, Nests on grassy tundra preferring dry (Pluvialis dominica) short bill; breeding males have a white including Seward Peninsula, then south along upland areas; nest in sparse lower crown stripe extending down the side of Norton Sound to Cape Romanzof. -

CA Checklist of Butterflies of Tulare County

Checklist of Buerflies of Tulare County hp://www.natureali.org/Tularebuerflychecklist.htm Tulare County Buerfly Checklist Compiled by Ken Davenport & designed by Alison Sheehey Swallowtails (Family Papilionidae) Parnassians (Subfamily Parnassiinae) A series of simple checklists Clodius Parnassian Parnassius clodius for use in the field Sierra Nevada Parnassian Parnassius behrii Kern Amphibian Checklist Kern Bird Checklist Swallowtails (Subfamily Papilioninae) Kern Butterfly Checklist Pipevine Swallowtail Battus philenor Tulare Butterfly Checklist Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes Kern Dragonfly Checklist Checklist of Exotic Animals Anise Swallowtail Papilio zelicaon (incl. nitra) introduced to Kern County Indra Swallowtail Papilio indra Kern Fish Checklist Giant Swallowtail Papilio cresphontes Kern Mammal Checklist Kern Reptile Checklist Western Tiger Swallowtail Papilio rutulus Checklist of Sensitive Species Two-tailed Swallowtail Papilio multicaudata found in Kern County Pale Swallowtail Papilio eurymedon Whites and Sulphurs (Family Pieridae) Wildflowers Whites (Subfamily Pierinae) Hodgepodge of Insect Pine White Neophasia menapia Photos Nature Ali Wild Wanderings Becker's White Pontia beckerii Spring White Pontia sisymbrii Checkered White Pontia protodice Western White Pontia occidentalis The Butterfly Digest by Cabbage White Pieris rapae Bruce Webb - A digest of butterfly discussion around Large Marble Euchloe ausonides the nation. Frontispiece: 1 of 6 12/26/10 9:26 PM Checklist of Buerflies of Tulare County hp://www.natureali.org/Tularebuerflychecklist.htm