Substrate-Mediated Reduction of the Diiron Center for 5-Demethoxyubiquinone Hydroxylation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Regulated Necrosis in Endocrine Diseases

PERSPECTIVES system results in the typical morphological features such as rapid shrinking of the cell, The role of regulated necrosis nuclear condensation, DNA fragmentation, exposure of phosphatidylserine and a in endocrine diseases process known as membrane blebbing11,12. Phosphatidylserine exposure functions Wulf Tonnus , Alexia Belavgeni , Felix Beuschlein , Graeme Eisenhofer, as an ‘eat me’ signal to macrophages13–15. Martin Fassnacht , Matthias Kroiss , Nils P. Krone, Martin Reincke , Importantly, the plasma membrane remains intact in apoptotically dying cells, Stefan R. Bornstein and Andreas Linkermann a mechanism that prevents the release of Abstract | The death of endocrine cells is involved in type 1 diabetes mellitus, intracellular content to the interstitial and/or autoimmunity, adrenopause and hypogonadotropism. Insights from research on extracellular space. Therefore, apoptosis is immunologically silent. The detection basic cell death have revealed that most pathophysiologically important cell death of apoptosis has been misinterpreted for is necrotic in nature, whereas regular metabolism is maintained by apoptosis decades by the TdT-mediated dUTP-biotin programmes. Necrosis is defined as cell death by plasma membrane rupture, which nick end- labelling (TUNEL) method (BOx 1). allows the release of damage- associated molecular patterns that trigger an Mechanistically, extrinsic apoptosis immune response referred to as necroinflammation. Regulated necrosis comes in is mediated by death receptors such as different forms, such as necroptosis, pyroptosis and ferroptosis. In this Perspective, tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1) or the FAS receptor (also known as with a focus on the endocrine environment, we introduce these cell death CD95)16. To kill a cell through a TNFR1 pathways and discuss the specific consequences of regulated necrosis. -

Relating Metatranscriptomic Profiles to the Micropollutant

1 Relating Metatranscriptomic Profiles to the 2 Micropollutant Biotransformation Potential of 3 Complex Microbial Communities 4 5 Supporting Information 6 7 Stefan Achermann,1,2 Cresten B. Mansfeldt,1 Marcel Müller,1,3 David R. Johnson,1 Kathrin 8 Fenner*,1,2,4 9 1Eawag, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, 8600 Dübendorf, 10 Switzerland. 2Institute of Biogeochemistry and Pollutant Dynamics, ETH Zürich, 8092 11 Zürich, Switzerland. 3Institute of Atmospheric and Climate Science, ETH Zürich, 8092 12 Zürich, Switzerland. 4Department of Chemistry, University of Zürich, 8057 Zürich, 13 Switzerland. 14 *Corresponding author (email: [email protected] ) 15 S.A and C.B.M contributed equally to this work. 16 17 18 19 20 21 This supporting information (SI) is organized in 4 sections (S1-S4) with a total of 10 pages and 22 comprises 7 figures (Figure S1-S7) and 4 tables (Table S1-S4). 23 24 25 S1 26 S1 Data normalization 27 28 29 30 Figure S1. Relative fractions of gene transcripts originating from eukaryotes and bacteria. 31 32 33 Table S1. Relative standard deviation (RSD) for commonly used reference genes across all 34 samples (n=12). EC number mean fraction bacteria (%) RSD (%) RSD bacteria (%) RSD eukaryotes (%) 2.7.7.6 (RNAP) 80 16 6 nda 5.99.1.2 (DNA topoisomerase) 90 11 9 nda 5.99.1.3 (DNA gyrase) 92 16 10 nda 1.2.1.12 (GAPDH) 37 39 6 32 35 and indicates not determined. 36 37 38 39 S2 40 S2 Nitrile hydration 41 42 43 44 Figure S2: Pearson correlation coefficients r for rate constants of bromoxynil and acetamiprid with 45 gene transcripts of ECs describing nucleophilic reactions of water with nitriles. -

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Metallomics

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Metallomics. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2018 Uniprot Entry name Gene names Protein names Predicted Pattern Number of Iron role EC number Subcellular Membrane Involvement in disease Gene ontology (biological process) Id iron ions location associated 1 P46952 3HAO_HUMAN HAAO 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4- H47-E53-H91 1 Fe cation Catalytic 1.13.11.6 Cytoplasm No NAD biosynthetic process [GO:0009435]; neuron cellular homeostasis dioxygenase (EC 1.13.11.6) (3- [GO:0070050]; quinolinate biosynthetic process [GO:0019805]; response to hydroxyanthranilate oxygenase) cadmium ion [GO:0046686]; response to zinc ion [GO:0010043]; tryptophan (3-HAO) (3-hydroxyanthranilic catabolic process [GO:0006569] acid dioxygenase) (HAD) 2 O00767 ACOD_HUMAN SCD Acyl-CoA desaturase (EC H120-H125-H157-H161; 2 Fe cations Catalytic 1.14.19.1 Endoplasmic Yes long-chain fatty-acyl-CoA biosynthetic process [GO:0035338]; unsaturated fatty 1.14.19.1) (Delta(9)-desaturase) H160-H269-H298-H302 reticulum acid biosynthetic process [GO:0006636] (Delta-9 desaturase) (Fatty acid desaturase) (Stearoyl-CoA desaturase) (hSCD1) 3 Q6ZNF0 ACP7_HUMAN ACP7 PAPL PAPL1 Acid phosphatase type 7 (EC D141-D170-Y173-H335 1 Fe cation Catalytic 3.1.3.2 Extracellular No 3.1.3.2) (Purple acid space phosphatase long form) 4 Q96SZ5 AEDO_HUMAN ADO C10orf22 2-aminoethanethiol dioxygenase H112-H114-H193 1 Fe cation Catalytic 1.13.11.19 Unknown No oxidation-reduction process [GO:0055114]; sulfur amino acid catabolic process (EC 1.13.11.19) (Cysteamine -

Mechanistic Study of Cysteine Dioxygenase, a Non-Heme

MECHANISTIC STUDY OF CYSTEINE DIOXYGENASE, A NON-HEME MONONUCLEAR IRON ENZYME by WEI LI Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2014 Copyright © by Student Name Wei Li All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Pierce for your mentoring, guidance and patience over the five years. I cannot go all the way through this without your help. Your intelligence and determination has been and will always be an example for me. I would like to thank my committee members Dr. Dias, Dr. Heo and Dr. Jonhson- Winters for the directions and invaluable advice. I also would like to thank all my lab mates, Josh, Bishnu ,Andra, Priyanka, Eleanor, you all helped me so I could finish my projects. I would like to thank the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry for the help with my academic and career. At Last, I would like to thank my lovely wife and beautiful daughter who made my life meaningful and full of joy. July 11, 2014 iii Abstract MECHANISTIC STUDY OF CYSTEINE DIOXYGENASE A NON-HEME MONONUCLEAR IRON ENZYME Wei Li, PhD The University of Texas at Arlington, 2014 Supervising Professor: Brad Pierce Cysteine dioxygenase (CDO) is an non-heme mononuclear iron enzymes that catalyzes the O2-dependent oxidation of L-cysteine (Cys) to produce cysteine sulfinic acid (CSA). CDO controls cysteine levels in cells and is a potential drug target for some diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzhermer’s. -

Springer Handbook of Enzymes

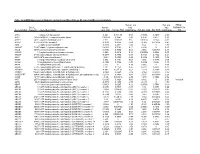

Dietmar Schomburg and Ida Schomburg (Eds.) Springer Handbook of Enzymes Volume 25 Class 1 • Oxidoreductases X EC 1.9-1.13 co edited by Antje Chang Second Edition 4y Springer Index of Recommended Enzyme Names EC-No. Recommended Name Page 1.13.11.50 acetylacetone-cleaving enzyme 673 1.10.3.4 o-aminophenol oxidase 149 1.13.12.12 apo-/?-carotenoid-14',13'-dioxygenase 732 1.13.11.34 arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase 591 1.13.11.40 arachidonate 8-lipoxygenase 627 1.13.11.31 arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase 568 1.13.11.33 arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase 585 1.13.12.1 arginine 2-monooxygenase 675 1.13.11.13 ascorbate 2,3-dioxygenase 491 1.10.2.1 L-ascorbate-cytochrome-b5 reductase 79 1.10.3.3 L-ascorbate oxidase 134 1.11.1.11 L-ascorbate peroxidase 257 1.13.99.2 benzoate 1,2-dioxygenase (transferred to EC 1.14.12.10) 740 1.13.11.39 biphenyl-2,3-diol 1,2-dioxygenase 618 1.13.11.22 caffeate 3,4-dioxygenase 531 1.13.11.16 3-carboxyethylcatechol 2,3-dioxygenase 505 1.13.11.21 p-carotene 15,15'-dioxygenase (transferred to EC 1.14.99.36) 530 1.11.1.6 catalase 194 1.13.11.1 catechol 1,2-dioxygenase 382 1.13.11.2 catechol 2,3-dioxygenase 395 1.10.3.1 catechol oxidase 105 1.13.11.36 chloridazon-catechol dioxygenase 607 1.11.1.10 chloride peroxidase 245 1.13.11.49 chlorite O2-lyase 670 1.13.99.4 4-chlorophenylacetate 3,4-dioxygenase (transferred to EC 1.14.12.9) . -

Transcriptome Analysis of Pistacia Vera Inflorescence Buds in Bearing

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Transcriptome Analysis of Pistacia vera Inflorescence Buds in Bearing and Non-Bearing Shoots Reveals the Molecular Mechanism Causing Premature Flower Bud Abscission Jubina Benny 1, Francesco Paolo Marra 2,* , Antonio Giovino 3, Bipin Balan 1,4, Tiziano Caruso 1, Federico Martinelli 5 and Annalisa Marchese 1,* 1 Department of Agricultural, Food and Forest Sciences, University of Palermo, Viale delle Scienze—Ed. 4, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (B.B.); [email protected] (T.C.) 2 Department of Architecture (DARCH), University of Palermo, Viale delle Scienze—Ed. 8, 90128 Palermo, Italy 3 Council for Agricultural Research and Economics (CREA), Research Centre for Plant Protection and Certification (CREA-DC), 90011 Bagheria, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA 5 Department of Biology, University of Florence, Sesto Fiorentino, 50019 Florence, Italy; federico.martinelli@unifi.it * Correspondence: [email protected] (F.P.M.); [email protected] (A.M.) Received: 23 June 2020; Accepted: 23 July 2020; Published: 25 July 2020 Abstract: The alteration of heavy (“ON/bearing”) and light (“OFF/non-bearing”) yield in pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) has been reported to result from the abscission of inflorescence buds on high yielding trees during the summer, but the regulatory mechanisms involved in this bud abscission remain unclear. The analysis provides insights into the transcript changes between inflorescence buds on bearing and non-bearing shoots, that we indicated as “ON” and “OFF”, and shed light on the molecular mechanisms causing premature inflorescence bud abscission in the pistachio cultivar “Bianca” which can be related to the alternate bearing behavior. -

And Fe(II)-Dependent Oxygenase Superfamily Protein(AT4G10500)

AGI code Name At4g10500 2-oxoglutarate (2OG) and Fe(II)-dependent oxygenase superfamily protein(AT4G10500) GOTERM_BP_DIRECT defense response to oomycetes, response to oomycetes, response to bacterium, response to fungus, response to salicylic acid, leaf senescence, secondary metabolic process, salicylic acid catabolic process, oxidation-reduction process, GOTERM_MF_DIRECT oxidoreductase activity, acting on paired donors, with incorporation or reduction of molecular oxygen, 2-oxoglutarate as one donor, and incorporation of one atom each of oxygen into both donors, metal ion binding, dioxygenase activity, At5g59540 2-oxoglutarate (2OG) and Fe(II)-dependent oxygenase superfamily protein(AT5G59540) GOTERM_BP_DIRECT oxidation-reduction process, GOTERM_CC_DIRECT cytoplasm, GOTERM_MF_DIRECT oxidoreductase activity, metal ion binding, dioxygenase activity, At3g55090 ABC-2 type transporter family protein(ABCG16) GOTERM_BP_DIRECT pollen wall assembly, GOTERM_CC_DIRECT plasma membrane, integral component of membrane, GOTERM_MF_DIRECT ATP binding, ATPase activity, coupled to transmembrane movement of substances, At2g37360 ABC-2 type transporter family protein(ABCG2) GOTERM_BP_DIRECT transport, suberin biosynthetic process, GOTERM_CC_DIRECT plasma membrane, integral component of membrane, GOTERM_MF_DIRECT ATP binding, ATPase activity, ATPase activity, coupled to transmembrane movement of substances, At3g47780 ABC2 homolog 6(ABCA7) GOTERM_BP_DIRECT lipid transport, GOTERM_CC_DIRECT plasma membrane, plasmodesma, integral component of membrane, intracellular -

Supplementary Material

Table S1 . Genes up-regulated in the CL of stimulated in relation to control animals ( 1.5 fold, P ≤ 0.05). UniGene ID Gene Title Gene Symbol fold change P value Bt.16350.2.A1_s_at guanylate binding protein 5 GBP5 4.42 0.002 Bt.2498.2.A1_a_at fibrinogen gamma chain FGG 3.81 0.002 Bt.440.1.S1_at neurotensin NTS 3.74 0.036 major histocompatibility complex, class I, A /// major Bt.27760.1.S1_at histocompatibility complex, class I, A BoLA /// HLA-A 3.56 0.022 Bt.146.1.S1_at defensin, beta 4A DEFB4A 3.12 0.002 Bt.7165.1.S1_at chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 CXCL5 3.06 0.031 Bt.15731.1.A1_at V-set and immunoglobulin domain containing 4 VSIG4 3.03 0.047 Bt.22869.1.S2_at fatty acid binding protein 5 (psoriasis-associated) FABP5 3.02 0.006 Bt.4604.1.S1_a_at acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 1 ACSM1 2.93 0.001 Bt.6406.1.S3_at CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), delta CEBPD 2.92 0.011 Bt.19845.2.A1_at coagulation factor XIII, A1 polypeptide F13A1 2.83 0.005 Bt.209.3.S1_at lysozyme (renal amyloidosis) LYZ 2.77 0.0003 Bt.15908.1.S1_at methyltransferase like 7A METTL7A 2.59 0.007 Bt.28383.1.S1_at granulysin GNLY 2.58 0.034 Bt.20455.1.S1_at Microtubule-associated protein tau MAPT 2.56 0.047 Bt.6556.1.S1_at regakine 1 LOC504773 2.55 0.011 Bt.11259.1.S1_at putative ISG12(a) protein ISG12(A) 2.55 0.037 Bt.28243.1.S1_a_at vanin 1 VNN1 2.54 0.008 Bt.405.1.S1_at follistatin FST 2.52 0.002 Bt.9510.2.A1_a_at T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing 4 TIMD4 2.47 0.024 Bt.499.1.S1_a_at prolactin receptor PRLR 2.44 0.010 serpin peptidase -

Inositol and Higher Inositol Phosphates in Neural Tissues: Homeostasis, Metabolism and Functional Significance

Journal of Neurochemistry, 2002, 82, 736–754 REVIEW Inositol and higher inositol phosphates in neural tissues: homeostasis, metabolism and functional significance Stephen K. Fisher,*, James E. Novak*, and Bernard W. Agranoff*,à *Mental Health Research Institute, and Departments of Pharmacology, and àBiochemistry and Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA Abstract its hexakisphosphate and pyrophosphorylated derivatives Inositol phospholipids and inositol phosphates mediate well- may play roles in such diverse cellular functions as DNA established functions in signal transduction and in Ca2+ repair, nuclear RNA export and synaptic membrane traf- homeostasis in the CNS and non-neural tissues. More ficking. recently, there has been renewed interest in other roles that Keywords: affective disorder and treatment, diphosphoino- both myo-inositol and its highly phosphorylated forms may sitol polyphosphates, inositol hexakisphosphate, lithium, Na+/ play in neural function. We review evidence that myo-inositol myo-inositol transporter, phytate. serves as a clinically relevant osmolyte in the CNS, and that J. Neurochem. (2002) 82, 736–754. The prominent role of inositol phospholipids in signal (namely, inositol hexakisphosphate and the diphosphoino- transduction events within the CNS is now well established sitol polyphosphates) may play in neural function. The CNS (for reviews, see Fisher and Agranoff 1987; Fisher et al. is an atypical tissue in that it possesses relatively high 1992). In addition, roles for phosphoinositides as facilitators concentrations of myo-inositol as well as the means to of a diverse array of cellular events, such as membrane synthesize it. myo-Inositol serves not only as a precursor trafficking, maintenance of the actin cytoskeleton, regulation molecule for inositol lipid synthesis, but also as a physi- of cell death and survival, and anchors for plasma membrane ologically important osmolyte. -

Mrna Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats As Measured by Microarray Analysis

Table 3S: mRNA Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats as Measured by Microarray Analysis Human_avg Rat_avg_ PENG_ Entrez. Human_ log2_ log2_ RAPAMYCIN Gene.Symbol Gene.ID Gene Description avg_tstat Human_FDR foldChange Rat_avg_tstat Rat_FDR foldChange _DN A1BG 1 alpha-1-B glycoprotein 4.982 9.52E-05 0.68 -0.8346 0.4639 -0.38 A1CF 29974 APOBEC1 complementation factor -0.08024 0.9541 -0.02 0.9141 0.421 0.10 A2BP1 54715 ataxin 2-binding protein 1 2.811 0.01093 0.65 0.07114 0.954 -0.01 A2LD1 87769 AIG2-like domain 1 -0.3033 0.8056 -0.09 -3.365 0.005704 -0.42 A2M 2 alpha-2-macroglobulin -0.8113 0.4691 -0.03 6.02 0 1.75 A4GALT 53947 alpha 1,4-galactosyltransferase 0.4383 0.7128 0.11 6.304 0 2.30 AACS 65985 acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase 0.3595 0.7664 0.03 3.534 0.00388 0.38 AADAC 13 arylacetamide deacetylase (esterase) 0.569 0.6216 0.16 0.005588 0.9968 0.00 AADAT 51166 aminoadipate aminotransferase -0.9577 0.3876 -0.11 0.8123 0.4752 0.24 AAK1 22848 AP2 associated kinase 1 -1.261 0.2505 -0.25 0.8232 0.4689 0.12 AAMP 14 angio-associated, migratory cell protein 0.873 0.4351 0.07 1.656 0.1476 0.06 AANAT 15 arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase -0.3998 0.7394 -0.08 0.8486 0.456 0.18 AARS 16 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 5.517 0 0.34 8.616 0 0.69 AARS2 57505 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 2, mitochondrial (putative) 1.701 0.1158 0.35 0.5011 0.6622 0.07 AARSD1 80755 alanyl-tRNA synthetase domain containing 1 4.403 9.52E-05 0.52 1.279 0.2609 0.13 AASDH 132949 aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase -0.8921 0.4247 -0.12 -2.564 0.02993 -0.32 AASDHPPT 60496 aminoadipate-semialdehyde -

A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of High-LET Ionizing Radiations in Human Gene Expression

Supplementary Materials A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of High-LET Ionizing Radiations in Human Gene Expression Table S1. Statistically significant DEGs (Adj. p-value < 0.01) derived from meta-analysis for samples irradiated with high doses of HZE particles, collected 6-24 h post-IR not common with any other meta- analysis group. This meta-analysis group consists of 3 DEG lists obtained from DGEA, using a total of 11 control and 11 irradiated samples [Data Series: E-MTAB-5761 and E-MTAB-5754]. Ensembl ID Gene Symbol Gene Description Up-Regulated Genes ↑ (2425) ENSG00000000938 FGR FGR proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase ENSG00000001036 FUCA2 alpha-L-fucosidase 2 ENSG00000001084 GCLC glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit ENSG00000001631 KRIT1 KRIT1 ankyrin repeat containing ENSG00000002079 MYH16 myosin heavy chain 16 pseudogene ENSG00000002587 HS3ST1 heparan sulfate-glucosamine 3-sulfotransferase 1 ENSG00000003056 M6PR mannose-6-phosphate receptor, cation dependent ENSG00000004059 ARF5 ADP ribosylation factor 5 ENSG00000004777 ARHGAP33 Rho GTPase activating protein 33 ENSG00000004799 PDK4 pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 ENSG00000004848 ARX aristaless related homeobox ENSG00000005022 SLC25A5 solute carrier family 25 member 5 ENSG00000005108 THSD7A thrombospondin type 1 domain containing 7A ENSG00000005194 CIAPIN1 cytokine induced apoptosis inhibitor 1 ENSG00000005381 MPO myeloperoxidase ENSG00000005486 RHBDD2 rhomboid domain containing 2 ENSG00000005884 ITGA3 integrin subunit alpha 3 ENSG00000006016 CRLF1 cytokine receptor like -

Open Dissertation Rajakovichlj.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Eberly College of Science EXPLORING THE FUNCTIONAL AND MECHANISTIC DIVERSITY OF DIIRON OXIDASES AND OXYGENASES A Dissertation in Biochemistry, Microbiology, and Molecular Biology by Lauren J. Rajakovich 2017 Lauren J. Rajakovich Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 ii The dissertation of Lauren J. Rajakovich was reviewed and approved* by the following: J. Martin Bollinger, Jr. Professor of Chemistry Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Dissertation Co-Advisor Committee Co-Chair Carsten Krebs Professor of Chemistry Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Dissertation Co-Advisor Committee Co-Chair Squire J. Booker Howard Hughes Medical Investigator Professor of Chemistry Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Amie K. Boal Professor of Chemistry Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Christopher House Professor of Geosciences Scott Selleck Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Head of the Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology, and Molecular Biology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Approximately half of all enzymes in Nature utilize a metal to perform their biological function. Many of the metalloenzymes that harbor transition metals activate dioxygen to catalyze a diverse array of oxidation reactions to functionalize unreactive sites in biomolecules. These enzymatic transformations are often inaccessible to synthetic chemists, and consequently, understanding the naturally-evolved mechanisms by which these enzymes enact such challenging reactions will enable the development of new biocatalysts for industrial and therapeutic applications. One common strategy employed in Nature is the coupling of two transition metals, typically iron, to carry out oxidation and oxygenation reactions.