The Firebird (1919 Version) I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday Playlist

October 31, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal.” — Igor Stravinsky Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Tchaikovsky Moscow Radio 00:01 Buy Now! Glinka Waltz Fantasie Harmonia Mundi 288 114 N/A Awake! Symphony/Fedoseyev 00:12 Buy Now! Schubert String Quartet No. 1, D. 18 Verdi Quartet Haenssler Classic 98.329 4010276009580 Rubinstein, 00:28 Buy Now! Piano Sonata No. 3 in F, Op. 41 Leslie Howard Hyperion 66017 034571160177 Anton 01:01 Buy Now! Salieri Concerto in C for Flute and Oboe Dohn/Sous/Wurttemberg Ch. Orch./Faerber Vox 7198 04716371982 01:22 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Ballet Music ~ The Maid of Orleans Royal Opera House Covent Garden/Davis Philips 422 845 028942284524 01:38 Buy Now! Rachmaninoff The Isle of the Dead, Op. 29 Royal Philharmonic/Litton Virgin 90830 075679083029 02:00 Buy Now! Balakirev Chopin Suite Singapore Symphony/Hoey Hong Kong 8.220324 N/A 02:22 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 Pine/Gottingen Symphony/Mueller Cedille 144 765131914420 02:49 Buy Now! Canning Fantasy on a Hymn by Justin Morgan Suzuki/Orlovsky/Indianapolis SO/Leppard Decca 458 157 028945845725 03:01 Buy Now! Bach Prelude and Fugue in G, BWV 541 Läubin Brass Ensemble DG 423 988 028942398825 String Sextet in D minor, Op. 70 "Souvenir of 03:09 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Bashmet/Gutman/Borodin Quartet EMI 49775 077774977524 Florence" 03:43 Buy Now! Grieg Lyric Suite, Op. 54 Malmö Symphony/Engeset Naxos 8.508015 747313801534 04:01 Buy Now! Strauss, R. -

Children's Concert Series an INTERACTIVE CONCERT WITH

Children’s Concert Series 2020–2021 AN INTERACTIVE CONCERT WITH MUSIC, DANCE, AND NARRATION Saturday, March 13, 2021 | 6:00 pm Virtual Family Concert 1 ver fifty years ago, a brave American man stepped out of a landing craft onto the surface Gerard Schwarz of the moon and made history. With the help of Conductor O the Demetrius Klein Dance Company and four exciting pieces of all-American music, Palm Beach Symphony Brenda Alford brings that indelible moment of Milky Way magic to the Narrator stage through an interactive concert in which students will literally take part in exploring such scientific concepts as Demetrius Klein Dance Company (DKDC) the Earth’s rotation, gravity and telescope viewing. All this choreography and dance while thrilling to a powerful Copland fanfare, the soaring themes of Star Wars and sharing the adventures of a very special resident of Earth’s satellite, Rocky de Luna, an Saturday, March 13, 2021 | 6:00 pm inquisitive moon rock. Virtual Family Concert With a special narrative accompanied by the music of Copland’s Lincoln Portrait, students will meet Rocky as she hitches a ride with two friendly NASA astronauts on the Program Apollo 11 lunar module en route back to Aaron Copland – Fanfare for the Common Man planet Earth. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin show Rocky some out-of-this-world John Williams – Princess Leia’s Theme from Star Wars views of the moon, help define the moon’s John Williams – The Imperial March (Darth Vader’s Theme) from Star Wars place in the solar system, describe how the moon Aaron Copland – Selections from Lincoln Portrait affects all life on Earth .. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

Paul Taylor Dance Company’S Engagement at Jacob’S Pillow Is Supported, in Part, by a Leadership Contribution from Carole and Dan Burack

PILLOWNOTES JACOB’S PILLOW EXTENDS SPECIAL THANKS by Suzanne Carbonneau TO OUR VISIONARY LEADERS The PillowNotes comprises essays commissioned from our Scholars-in-Residence to provide audiences with a broader context for viewing dance. VISIONARY LEADERS form an important foundation of support and demonstrate their passion for and commitment to Jacob’s Pillow through It is said that the body doesn’t lie, but this is wishful thinking. All earthly creatures do it, only some more artfully than others. annual gifts of $10,000 and above. —Paul Taylor, Private Domain Their deep affiliation ensures the success and longevity of the It was Martha Graham, materfamilias of American modern dance, who coined that aphorism about the inevitability of truth Pillow’s annual offerings, including educational initiatives, free public emerging from movement. Considered oracular since its first utterance, over time the idea has only gained in currency as one of programs, The School, the Archives, and more. those things that must be accurate because it sounds so true. But in gently, decisively pronouncing Graham’s idea hokum, choreographer Paul Taylor drew on first-hand experience— $25,000+ observations about the world he had been making since early childhood. To wit: Everyone lies. And, characteristically, in his 1987 autobiography Private Domain, Taylor took delight in the whole business: “I eventually appreciated the artistry of a movement Carole* & Dan Burack Christopher Jones* & Deb McAlister PRESENTS lie,” he wrote, “the guilty tail wagging, the overly steady gaze, the phony humility of drooping shoulders and caved-in chest, the PAUL TAYLOR The Barrington Foundation Wendy McCain decorative-looking little shuffles of pretended pain, the heavy, monumental dances of mock happiness.” Frank & Monique Cordasco Fred Moses* DANCE COMPANY Hon. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 59,1939

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 1492 FIFTY—NINTH SEASON, 1939-194o CONCERT BULLETIN OF THE Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor RICHARD BURGIN, Assistant Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by JOHN N. BURK COPYRIGHT, 1939, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. ERNEST B. DANE • • President HENRY B. SAWYER Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE . • Treasurer HENRY B. CABOT M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE ERNEST B. DANE ROGER I. LEE ALVAN T. FULLER RICHARD C. PAINE JEROME D. GREENE HENRY B. SAWYER N. PENROSE HALT OWELL EDWARD A. TAFT BENTLEY W. WARREN G. E. JUDD, Manager C. W. SPALDING, Assistant Manager ( 289 ) Complete FIDUCIARY SERVICE /^INDIVIDUALS The fiduciary services of Old Colony Trust Company available to individuals are many and varied. We cite some of the fiduciary capacities in which we act. Executor and Administrator We settle estates as Executor and Administrator. Trustee We act as Trustee under wills and under voluntary or living trusts. Agent We act as Agent for those who wish to be relieved of the care of their investments. The officers of Old Colony Trust Company are always glad to discuss estate and property matters with you and point out if and where our services are applicable. Old Colony Trust Company 17 COURT STREET, BOSTON Member of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation ^Allied w/'MThe First National Bank ^Boston [ 290] ,1 FIFTY-NINTH SEASON - NINETEEN HUNDRED THIRTY-NINE AND FORTY Seventh Programme FRIDAY AFTERNOON, December i, at 2:30 o'clock SATURDAY EVENING, December 2, at 8:15 o'clock IGOR STRAVINSKY Conducting Stravinsky "Jeu de Cartes" (Card Game, Ballet in Three Deals) (First performances at these concerts) Stravinsky Capriccio for Orchestra with Piano Solo I. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 125, 2005-2006

Tap, tap, tap. The final movement is about to begin. In the heart of This unique and this eight-acre gated final phase is priced community, at the from $1,625 million pinnacle of Fisher Hill, to $6.6 million. the original Manor will be trans- For an appointment to view formed into five estate-sized luxury this grand finale, please call condominiums ranging from 2,052 Hammond GMAC Real Estate to a lavish 6,650 square feet of at 617-731-4644, ext. 410. old world charm with today's ultra-modern comforts. BSRicJMBi EM ;\{? - S'S The path to recovery... a -McLean Hospital ', j Vt- ^Ttie nation's top psychiatric hospital. 1 V US NeWS & °r/d Re >0rt N£ * SE^ " W f see «*££% llffltlltl #•&'"$**, «B. N^P*^* The Pavijiorfat McLean Hospital Unparalleled psychiatric evaluation and treatment Unsurpassed discretion and service BeJmont, Massachusetts 6 1 7/855-3535 www.mclean.harvard.edu/pav/ McLean is the largest psychiatric clinical care, teaching and research affiliate R\RTNERSm of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate of Massachusetts General Hospital HEALTHCARE and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #78 bump-bump bump-bump bump-bump There are lots of reasons to choose Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like less invasive and more permanent cardiac arrhythmia treatments. And other innovative ways we're tending to matters of the heart in our renowned catheterization lab, cardiac MRI and peripheral vascular diseases units, and unique diabetes partnership with Joslin Clinic. From cardiology and oncology to sports medicine and gastroenterology, you'll always find care you can count on at BIDMC. -

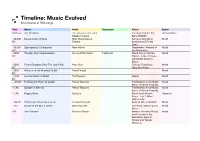

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

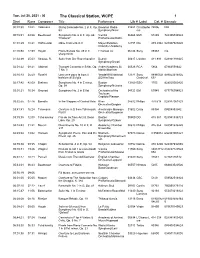

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jul 20, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 13:01 Volkmann String Serenade No. 2 in F, Op. Bavarian Radio 01487 Christopho 74506 N/A 63 Symphony/Nicol rus 00:15:3144:28 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 Vienna 06364 EMI 57445 724355744524 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Rattle 01:01:29 18:21 Hoffmeister Oboe Concerto in C Mayer/Potsdam 12355 DG 479 2942 028947929420 Chamber Academy 01:20:5012:59 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 49 in C Emanuel Ax 06244 Sony 89363 n/a sharp minor 01:34:49 25:03 Strauss, R. Suite from Der Rosenkavalier Detroit 00617 London 411 893 028941189325 Symphony/Dorati 02:01:2208:21 Albinoni Trumpet Concerto in B flat, Op. Andre/Academy St. 00526 RCA 5864 07863558642 7 No. 3 Martin/Marriner 02:10:43 05:59 Rossini Una voce poco fa from Il Yende/RAI National 12979 Sony 88985321 889853216925 barbiere di Siviglia SO/Armiliato Classical 692 02:17:4242:09 Brahms Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Boston 13169 BSO 1703 828020003425 Op. 98 Symphony/Nelsons 03:01:21 30:34 Gounod Symphony No. 2 in E flat Orchestra of the 04723 EMI 63949 077776394923 Toulouse Capitole/Plasson 03:32:5507:46 Borodin In the Steppes of Central Asia Kirov 08532 Philips 470 618 028947061823 Orchestra/Gergiev 03:41:4116:24 Telemann Overture in D from Tafelmusik, Amsterdam Baroque 01602 Erato 85394 08908853942 Part II Orchestra/Koopman 03:59:3512:08 Tchaikovsky Pas de six from Act III, Swan Boston 00500 DG 415 367 028941536723 Lake, Op. -

A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form

MODERN FORMS OF AN ANCIENT ART: A SELECTION OF CONTEMPORARY FANFARES FOR MULTIPLE TRUMPETS DEMONSTRATING EVOLUTIONARY PROCESSES IN THE FANFARE FORM Paul J. Florek, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2015 APPROVED: Keith Johnson, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Florek, Paul J. Modern Forms of an Ancient Art: A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2015, 73 pp., 1 table, 26 figures, references, 96 titles. The pieces discussed throughout this dissertation provide evidence of the evolution of the fanfare and the ability of the fanfare, as a form, to accept modern compositional techniques. While Britten’s Fanfare for St. Edmundsbury maintains the harmonic series, it does so by choice rather than by the necessity in earlier music played by the baroque trumpet. Stravinsky’s Fanfare from Agon applies set theory, modal harmonies, and open chords to blend modern techniques with medieval sounds. Satie’s Sonnerie makes use of counterpoint and a rather unusual, new characteristic for fanfares, soft dynamics. Ginastera’s Fanfare for Four Trumpets in C utilizes atonality and jazz harmonies while Stravinsky’s Fanfare for a New Theatre strictly coheres to twelve-tone serialism. McTee’s Fanfare for Trumpets applies half-step dissonance and ostinato patterns while Tower’s Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman demonstrates a multi-section work with chromaticism and tritones. -

Finding Aid for Bolender Collection

KANSAS CITY BALLET ARCHIVES BOLENDER COLLECTION Bolender, Todd (1914-2006) Personal Collection, 1924-2006 44 linear feet 32 document boxes 9 oversize boxes (15”x19”x3”) 2 oversize boxes (17”x21”x3”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x4”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x6”) 8 storage boxes 2 storage tubes; 1 trunk lid; 1 garment bag Scope and Contents The Bolender Collection contains personal papers and artifacts of Todd Bolender, dancer, choreographer, teacher and ballet director. Bolender spent the final third of his 70-year career in Kansas City, as Artistic Director of the Kansas City Ballet 1981-1995 (Missouri State Ballet 1986- 2000) and Director Emeritus, 1996-2006. Bolender’s records constitute the first processed collection of the Kansas City Ballet Archives. The collection spans Bolender’s lifetime with the bulk of records dating after 1960. The Bolender material consists of the following: Artifacts and memorabilia Artwork Books Choreography Correspondence General files Kansas City Ballet (KCB) / State Ballet of Missouri (SBM) files Music scores Notebooks, calendars, address books Photographs Postcard collection Press clippings and articles Publications – dance journals, art catalogs, publicity materials Programs – dance and theatre Video and audio tapes LK/January 2018 Bolender Collection, KCB Archives (continued) Chronology 1914 Born February 27 in Canton, Ohio, son of Charles and Hazel Humphries Bolender 1931 Studied theatrical dance in New York City 1933 Moved to New York City 1936-44 Performed with American Ballet, founded by -

A B C a B C D a B C D A

24 go symphonyorchestra chica symphony centerpresent BALL SYMPHONY anne-sophie mutter muti riccardo orchestra symphony chicago 22 september friday, highlight season tchaikovsky mozart 7:00 6:00 Mozart’s fiery undisputed queen ofviolin-playing” ( and Tchaikovsky’s in beloved masterpieces, including Rossini’s followed by Riccardo Muti leading the Chicago SymphonyOrchestra season. Enjoy afestive opento the preconcert 2017/18 reception, proudly presents aprestigious gala evening ofmusic and celebration The Board Women’s ofthe Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Gala package guests will enjoy postconcert dinner and dancing. rossini Suite from Suite 5 No. Concerto Violin to Overture C P s oncert reconcert Reception Turkish The Sleeping Beauty Concerto. The SleepingBeauty William Tell conducto The Times . Anne-Sophie Mutter, “the (Turkish) William Tell , London), performs London), , media sponsor: r violin Overture 10 Concerts 10 Concerts A B C A B 5 Concerts 5 Concerts D E F G H I 8 Concerts 5 Concerts E F G H 5 Concerts 6 Conc. 5 Concerts THU FRI FRI SAT SAT SUN TUE 8:00 1:30 8:00 2017/18 8:00 8:00 3:00 7:30 ABCABCD ABCDAAB Riccardo Muti conductor penderecki The Awakening of Jacob 9/23 9/26 Anne-Sophie Mutter violin tchaikovsky Violin Concerto schumann Symphony No. 2 C A 9/28 9/29 Riccardo Muti conductor rossini Overture to William Tell 10/1 ogonek New Work world premiere, cso commission A • F A bruckner Symphony No. 4 (Romantic) A Alain Altinoglu conductor prokoFIEV Suite from The Love for Three Oranges Sandrine Piau soprano poulenc Gloria Michael Schade tenor gounod Saint Cecilia Mass 10/5 10/6 Andrew Foster-Williams 10/7 C • E B bass-baritone B • G Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe chorus director 10/26 10/27 James Gaffigan conductor bernstein Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront James Ehnes violin barber Violin Concerto B • I A rachmaninov Symphonic Dances Sir András Schiff conductor mozart Serenade for Winds in C Minor 11/2 11/3 and piano bartók Divertimento for String Orchestra 11/4 11/5 A • G C bach Keyboard Concerto No. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies.