What Diplomats Need to Know About Canadian Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ONLINE INCIVILITY and ABUSE in CANADIAN POLITICS Chris

ONLINE INCIVILITY AND ABUSE IN CANADIAN POLITICS Chris Tenove Heidi Tworek TROLLED ON THE CAMPAIGN TRAIL ONLINE INCIVILITY AND ABUSE IN CANADIAN POLITICS CHRIS TENOVE • HEIDI TWOREK COPYRIGHT Copyright © 2020 Chris Tenove; Heidi Tworek; Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions, University of British Columbia. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. CITATION Tenove, Chris, and Heidi Tworek (2020) Trolled on the Campaign Trail: Online Incivility and Abuse in Canadian Politics. Vancouver: Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions, University of British Columbia. CONTACT DETAILS Chris Tenove, [email protected] (Corresponding author) Heidi Tworek, [email protected] CONTENTS AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES ..................................................................................................................1 RESEARCHERS ...............................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................5 FACING INCIVILITY IN #ELXN43 ....................................................................................................8 -

Understanding Stephen Harper

HARPER Edited by Teresa Healy www.policyalternatives.ca Photo: Hanson/THE Tom CANADIAN PRESS Understanding Stephen Harper The long view Steve Patten CANAdIANs Need to understand the political and ideological tem- perament of politicians like Stephen Harper — men and women who aspire to political leadership. While we can gain important insights by reviewing the Harper gov- ernment’s policies and record since the 2006 election, it is also essential that we step back and take a longer view, considering Stephen Harper’s two decades of political involvement prior to winning the country’s highest political office. What does Harper’s long record of engagement in conservative politics tell us about his political character? This chapter is organized around a series of questions about Stephen Harper’s political and ideological character. Is he really, as his support- ers claim, “the smartest guy in the room”? To what extent is he a con- servative ideologue versus being a political pragmatist? What type of conservatism does he embrace? What does the company he keeps tell us about his political character? I will argue that Stephen Harper is an economic conservative whose early political motivations were deeply ideological. While his keen sense of strategic pragmatism has allowed him to make peace with both conservative populism and the tradition- alism of social conservatism, he continues to marginalize red toryism within the Canadian conservative family. He surrounds himself with Governance 25 like-minded conservatives and retains a long-held desire to transform Canada in his conservative image. The smartest guy in the room, or the most strategic? When Stephen Harper first came to the attention of political observers, it was as one of the leading “thinkers” behind the fledgling Reform Party of Canada. -

BACKBENCHERS So in Election Here’S to You, Mr

Twitter matters American political satirist Stephen Colbert, host of his and even more SPEAKER smash show The Colbert Report, BACKBENCHERS so in Election Here’s to you, Mr. Milliken. poked fun at Canadian House Speaker Peter politics last week. p. 2 Former NDP MP Wendy Lill Campaign 2011. p. 2 Milliken left the House of is the writer behind CBC Commons with a little Radio’s Backbenchers. more dignity. p. 8 COLBERT Heard on the Hill p. 2 TWITTER TWENTY-SECOND YEAR, NO. 1082 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, APRIL 4, 2011 $4.00 Tories running ELECTION CAMPAIGN 2011 Lobbyists ‘pissed’ leaner war room, Prime Minister Stephen Harper on the hustings they can’t work on focused on election campaign, winning majority This campaign’s say it’s against their This election campaign’s war room Charter rights has 75 to 90 staffers, with the vast majority handling logistics of about one man Lobbying Commissioner Karen the Prime Minister’s tour. Shepherd tells lobbyists that working on a political By KRISTEN SHANE and how he’s run campaign advances private The Conservatives are running interests of public office holder. a leaner war room and a national campaign made up mostly of cam- the government By BEA VONGDOUANGCHANH paign veterans, some in new roles, whose goal is to persuade Canadi- Lobbyists are “frustrated” they ans to re-elect a “solid, stable Con- can’t work on the federal elec- servative government” to continue It’s a Harperendum, a tion campaign but vow to speak Canada’s economic recovery or risk out against a regulation that they a coalition government headed by national verdict on this think could be an unconstitutional Liberal Leader Michael Ignatieff. -

Toronto to Have the Canadian Jewish News Area Canada Post Publication Agreement #40010684 Havdalah: 7:53 Delivered to Your Door Every Week

SALE FOR WINTER $1229 including 5 FREE hotel nights or $998* Air only. *subject to availabilit/change Call your travel agent or EL AL. 416-967-4222 60 Pages Wednesday, September 26, 2007 14 Tishrei, 5768 $1.00 This Week Arbour slammed by two groups National Education continues Accused of ‘failing to take a balanced approach’ in Mideast conflict to be hot topic in campaign. Page 3 ognizing legitimate humanitarian licly against the [UN] Human out publicly about Iran’s calls for By PAUL LUNGEN needs of the Palestinians, we regret Rights Council’s one-sided obses- genocide.” The opportunity was Rabbi Schild honoured for Staff Reporter Arbour’s repeated re- sion with slamming there, he continued, because photos 60 years of service Page 16 sort to a one-sided Israel. As a former published after the event showed Louise Arbour, the UN high com- narrative that denies judge, we urge her Arbour, wearing a hijab, sitting Bar mitzvah boy helps missioner for Human Rights, was Israelis their essential to adopt a balanced close to the Iranian president. Righteous Gentile. Page 41 slammed by two watchdog groups right to self-defence.” approach.” Ahmadinejad was in New York last week for failing to take a bal- Neuer also criti- Neuer was refer- this week to attend a UN confer- Heebonics anced approach to the Arab-Israeli cized Arbour, a former ring to Arbour’s par- ence. His visit prompted contro- conflict and for ignoring Iran’s long- Canadian Supreme ticipation in a hu- versy on a number of fronts. Co- standing call to genocide when she Court judge, for miss- man rights meeting lumbia University, for one, came in attended a human rights conference ing an opportunity to of the Non-Aligned for a fair share of criticism for invit- in Tehran earlier this month. -

Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives $6.95

CANADIAN CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES MAY/JUNE 2018 $6.95 Contributors Ricardo Acuña is Director of Alex Himelfarb is a former Randy Robinson is a the Parkland Institute and federal government freelance researcher, sits on the CCPA’s Member’s executive with the Privy educator and political Council. Council, Treasury Board, and commentator based in Vol. 25, No. 1 numerous other departments, Toronto. Alyssa O’Dell is Media and ISSN 1198-497X and currently chairs or serves Public Relations Officer at the Luke Savage writes and Canada Post Publication 40009942 on various voluntary boards. CCPA. blogs about politics, labour, He chairs the advisory board The Monitor is published six times philosophy and political a year by the Canadian Centre for Marc Edge is a professor of of the CCPA-Ontario. culture. Policy Alternatives. media and communication Elaine Hughes is an at University Canada West Edgardo Sepulveda is an The opinions expressed in the environmental activist in in Vancouver. His last book, independent consulting Monitor are those of the authors several non-profit groups and do not necessarily reflect The News We Deserve: The economist with more than including the Council of the views of the CCPA. Transformation of Canada’s two decades of utility Canadians, where she chairs Media Landscape, was (telecommunications) policy Please send feedback to the Quill Plains (Wynyard), published by New Star Books and regulatory experience. [email protected]. Saskatchewan chapter. in 2016. He writes about electricity, Editor: Stuart Trew Syed Hussan is Co-ordinator inequality and other Senior Designer: Tim Scarth Matt Elliott is a city columnist of the Migrant Workers economic policy issues at Layout: Susan Purtell and blogger with Metro Editorial Board: Peter Bleyer, Alliance for Change. -

Views Dropped and 250 the Oldest Each Week Group of Rolling Where Week Average Data the Is Based Afour on 2021

Federal Liberal brand trending up, Conservative brand trending down in Nanos Party Power Index Nanos Weekly Tracking, ending March 26, 2021 (released March 30, 2021) Ideas powered by NANOS world-class data © NANOSRESEARCH Nanos tracks unprompted issues of concern every week and is uniquely positioned to monitor the trajectory of opinion on Covid-19. This first was on the Nanos radar the week of January 24, 2020. To access full weekly national and regional tracking visit the Nanos subscriber data portal. The Nanos Party Power Index is a composite score of the brand power of parties and is made up of support, leader evaluations, and accessible voter measures. Over the past four weeks the federal Liberal score has been trending up while the federal Conservative score has been trending down. Nik Nanos © NANOS RESEARCH © NANOS NANOS 2 ISSUE TRACKING - CORONAVIRUS 1,000 random interviews recruited from and RDD land- Question: What is your most important NATIONAL issue of concern? [UNPROMPTED] and cell-line sample of Source: Nanos weekly tracking ending March 26, 2021. Canadians age 18 years and 55 over, ending March 26, 2021. The data is based on a four 50 week rolling average where each week the oldest group of 45 250 interviews is dropped and 42.8 a new group of 250 is added. 40 A random survey of 1,000 Canadians is accurate 3.1 35 percentage points, plus or minus, 19 times out of 20. 30 25 Contact: Nik Nanos 20.5 [email protected] Ottawa: (613) 234-4666 x 237 20 Website: www.nanos.co 15.4 Methodology: 15 www.nanos.co/method 10 12.3 11.1 Subscribe to the Nanos data 6.9 portals to get access to 5 6.7 0.0 detailed breakdowns for $5 a month. -

ON TRACK Vol 16 No 4 V2.Indd

INDEPENDENT AND INFORMED • AUTONOME ET RENSEIGNÉ ON TRACK The Conference of Defence Associations Institute • L’Institut de la Conférence des Associations de la Défense Winter 2011/12 • Volume 16, Number 4 Hiver 2011/12 • VolumeHiver 16,2011 Numéro / 12 • Volume 4 16, Numéro 4 LLIBYA:IBYA: CCanada’sanada’s ContributionContribution EExaminingxamining NATONATO inin a StormyStormy CenturyCentury CCanadaanada andand thethe UNUN SecuritySecurity CouncilCouncil ON TRACK VOLUME 16 NUMBER 4: WINTER / HIVER 2011/2012 PRESIDENT / PRÉSIDENT Dr. John Scott Cowan, BSc, MSc, PhD VICE PRESIDENT / VICE PRÉSIDENT Général (Ret’d) Raymond Henault, CMM, CD EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR / DIRECTEUR EXÉCUTIF CDA INSTITUTE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Colonel (Ret) Alain M. Pellerin, OMM, CD, MA LE CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION DE L’INSTITUT DE LA CAD SECRETARY-TREASURER / SECRÉTAIRE TRÉSORIER Lieutenant-Colonel (Ret’d) Gordon D. Metcalfe, CD Admiral (Ret’d) John Anderson HONOURARY COUNSEL / AVOCAT-CONSEIL HONORAIRE Mr. Thomas d’Aquino Mr. Robert T. Booth, QC, B Eng, LL B Dr. David Bercuson DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH / Dr. Douglas Bland DIRECTEUR DE LA RECHERCHE Colonel (Ret’d) Brett Boudreau Mr. Paul Chapin Dr. Ian Brodie PUBLIC AFFAIRS / RELATIONS PUBLIQUES Mr. Thomas S. Caldwell Captain (Ret’d) Peter Forsberg, CD Mr. Mel Cappe DEFENCE POLICY ANALYSTS / ANALYSTES DES POLITIQUES DE DÉFENSE Mr. Jamie Carroll Ms. Meghan Spilka O’Keefe, MA Dr. Jim Carruthers Mr. Arnav Manchanda, MA Mr. Dave Perry, MA Mr. Paul H. Chapin Mr. Terry Colfer PROJECT OFFICER / AGENT DE PROJET Mr. Paul Hillier, MA M. Jocelyn Coulon Conference of Defence Associations Institute Dr. John Scott Cowan 151 Slater Street, Suite 412A Mr. Dan Donovan Ottawa ON K1P 5H3 Lieutenant-général (Ret) Richard Evraire PHONE / TÉLÉPHONE Honourary Lieutenant-Colonel Justin Fogarty (613) 236 9903 Colonel, The Hon. -

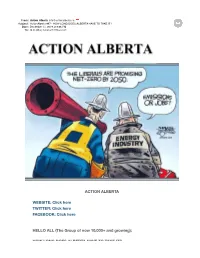

Actionalberta 87 HOW LONG DOES ALBERTA HAVE to TAKE IT

From: Action Alberta [email protected] Subject: ActionAlberta #87 - HOW LONG DOES ALBERTA HAVE TO TAKE IT? Date: December 11, 2019 at 8:06 PM To: Q.C. Alta.) [email protected] ACTION ALBERTA WEBSITE: Click here TWITTER: Click here FACEBOOK: Click here HELLO ALL (The Group of now 10,000+ and growing): HOW LONG DOES ALBERTA HAVE TO TAKE IT? HOW LONG DOES ALBERTA HAVE TO TAKE IT? (Robert J. Iverach, Q.C.) What Justin Trudeau and his Liberal government have intentionally done to the Western oil and gas industry is treason to all Canadians' prosperity. This is especially true when you consider that the East Coast fishing industry has been decimated, Ontario manufacturing is slumping and now the B.C. forest industry is in the tank. Justin Trudeau is killing our source of wealth. Alberta is in a "legislated recession" - a recession created by our federal government with its anti-business/anti-oil and gas legislation, such as Bill C-48 (the "West coast tanker ban") and Bill C-69 (the "pipeline ban"). This legislation has now caused at least $100 Billion of new and existing investment to flee Western Canada. Last month, Canada lost 72,000 jobs and 18,000 of those were in Alberta! Unemployment in Alberta has now risen to 7.2% with a notable increase in unemployment in the natural resources sector, while the unemployment rate for men under 25 years of age is now at almost 20%. How long must Albertans put up with the deliberate actions of a federal government that is intentionally killing our oil and gas business? When will Albertans say enough is enough? Well to this humble Albertan, the time is now! THE INEVITABLE TRUDEAU RECESSION WILL RAVAGE THE WEST AND THE MIDDLE CLASS (Diane Francis) The “hot mic” video of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau mocking President Donald Trump behind his back at the NATO conference is a major diplomatic blunder. -

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

A Parliamentarian's

A Parliamentarian’s Year in Review 2018 Table of Contents 3 Message from Chris Dendys, RESULTS Canada Executive Director 4 Raising Awareness in Parliament 4 World Tuberculosis Day 5 World Immunization Week 5 Global Health Caucus on HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria 6 UN High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis 7 World Polio Day 8 Foodies That Give A Fork 8 The Rush to Flush: World Toilet Day on the Hill 9 World Toilet Day on the Hill Meetings with Tia Bhatia 9 Top Tweet 10 Forging Global Partnerships, Networks and Connections 10 Global Nutrition Leadership 10 G7: 2018 Charlevoix 11 G7: The Whistler Declaration on Unlocking the Power of Adolescent Girls in Sustainable Development 11 Global TB Caucus 12 Parliamentary Delegation 12 Educational Delegation to Kenya 14 Hearing From Canadians 14 Citizen Advocates 18 RESULTS Canada Conference 19 RESULTS Canada Advocacy Day on the Hill 21 Engagement with the Leaders of Tomorrow 22 United Nations High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis 23 Pre-Budget Consultations Message from Chris Dendys, RESULTS Canada Executive Director “RESULTS Canada’s mission is to create the political will to end extreme poverty and we made phenomenal progress this year. A Parliamentarian’s Year in Review with RESULTS Canada is a reminder of all the actions decision makers take to raise their voice on global poverty issues. Thank you to all the Members of Parliament and Senators that continue to advocate for a world where everyone, no matter where they were born, has access to the health, education and the opportunities they need to thrive. “ 3 Raising Awareness in Parliament World Tuberculosis Day World Tuberculosis Day We want to thank MP Ziad Aboultaif, Edmonton MPs Dean Allison, Niagara West, Brenda Shanahan, – Manning, for making a statement in the House, Châteauguay—Lacolle and Senator Mobina Jaffer draw calling on Canada and the world to commit to ending attention to the global tuberculosis epidemic in a co- tuberculosis, the world’s leading infectious killer. -

Fall 2013 / Winter 2014 Titles

INFLUENTIAL THINKERS INNOVATIVE IDEAS GRANTA PAYBACK THE WAYFINDERS RACE AGAINST TIME BECOMING HUMAN Margaret Atwood Wade Davis Stephen Lewis Jean Vanier Trade paperback / $18.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 ANANSIANANSIANANSI 978-0-88784-810-0 978-0-88784-842-1 978-0-88784-753-0 978-0-88784-809-4 PORTOBELLO e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 978-0-88784-872-8 978-0-88784-969-5 978-0-88784-875-9 978-0-88784-845-2 A SHORT HISTORY THE TRUTH ABOUT THE UNIVERSE THE EDUCATED OF PROGRESS STORIES WITHIN IMAGINATION FALL 2013 / Ronald Wright Thomas King Neil Turok Northrop Frye Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $19.95 Trade paperback / $14.95 978-0-88784-706-6 978-0-88784-696-0 978-1-77089-015-2 978-0-88784-598-7 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $16.95 e-book / $14.95 WINTER 2014 978-0-88784-843-8 978-0-88784-895-7 978-1-77089-225-5 978-0-88784-881-0 ANANSI PUBLISHES VERY GOOD BOOKS WWW.HOUSEOFANANSI.COM Anansi_F13_cover.indd 1-2 13-05-15 11:51 AM HOUSE OF ANANSI FALL 2013 / WINTER 2014 TITLES SCOTT GRIFFIN Chair NONFICTION ... 1 SARAH MACLACHLAN President & Publisher FICTION ... 17 ALLAN IBARRA VP Finance ASTORIA (SHORT FICTION) ... 23 MATT WILLIAMS VP Publishing Operations ARACHNIDE (FRENCH TRANSLATION) ... 29 JANIE YOON Senior Editor, Nonfiction ANANSI INTERNATIONAL ... 35 JANICE ZAWERBNY Senior Editor, Canadian Fiction SPIDERLINE .. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} No Relation by Terry Fallis ISBN 13: 9780771036163

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} No Relation by Terry Fallis ISBN 13: 9780771036163. In his fourth novel, winner of the 2011 Canada Reads competition and "CanLit's crowned king of chuckles" ( Telegraph-Journal ) Terry Fallis's sharp, funny wit takes readers into the world of identity, inheritance, and belonging, begging the question: What's in a name? This is the story of a young copywriter in New York City. He's worked at the same agency for fifteen years, and with a recent promotion under his belt, life is good. Then, one morning this copywriter finds himself unceremoniously fired from his job, and after he catches his live-in girlfriend moving out of their apartment a couple hours later, he's also single. Believe it or not, these aren't the biggest problems in this copywriter's life. There's something bigger, something that has been haunting him his whole life, something that he'll never be able to shake. Meet Earnest Hemmingway. What's in a name? Well, if you share your moniker with the likes of some of the most revered, infamous, and sometimes dreaded names in history, plenty. This is Earnest's lifelong plight, but something more recent is on his plate: His father is pressuring him to come home and play an active role in running the family clothing business. And as a complex familial battle plays out, Earnest's inherited name leads him in unexpected directions. Wry, clever, and utterly engaging, No Relation is Terry Fallis at the top of his form. "synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.