Background to Prehistory of the Yuha Desert Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M O J a V E D E S E R T I S S U E S a Secondary

MOJAVE DESERT ISSUES A Secondary School Curriculum Bruce W. Bridenbecker & Darleen K. Stoner, Ph.D. Research Assistant Gail Uchwat Mojave Desert Issues was funded with a grant from the National Park �� Foundation. Parks as Classrooms is the educational program of the National ����� �� ���������� Park Service in partnership with the National Park Foundation. Design by Amy Yee and Sandra Kaye Published in 1999 and printed on recycled paper ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to the following people for their contribution to this work: Elayn Briggs, Bureau of Land Management Caryn Davidson, National Park Service Larry Ellis, Banning High School Lorenza Fong, National Park Service Veronica Fortun, Bureau of Land Management Corky Hays, National Park Service Lorna Lange-Daggs, National Park Service Dave Martell, Pinon Mesa Middle School David Moore, National Park Service Ruby Newton, National Park Service Carol Peterson, National Park Service Pete Ricards, Twentynine Palms Highschool Kay Rohde, National Park Service Dennis Schramm, National Park Service Jo Simpson, Bureau of Land Management Kirsten Talken, National Park Service Cindy Zacks, Yucca Valley Highschool Joe Zarki, National Park Service The following specialists provided information: John Anderson, California Department of Fish & Game Dave Bieri, National Park Service �� John Crossman, California Department of Parks and Recreation ����� �� ���������� Don Fife, American Land Holders Association Dana Harper, National Park Service Judy Hohman, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Becky Miller, California -

Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 Is a Mountainous, Deeply Dissected, and Westerly Tilting Fault Block

5 . S i e r r a N e v a d a Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 is a mountainous, deeply dissected, and westerly tilting fault block. It is largely composed of granitic rocks that are lithologically distinct from the sedimentary rocks of the Klamath Mountains (78) and the volcanic rocks of the Cascades (4). A Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies Literature Cited: high fault scarp divides the Sierra Nevada (5) from the Northern Basin and Range (80) and Central Basin and Range (13) to the 2 2 . A r i z o n a / N e w M e x i c o P l a t e a u east. Near this eastern fault scarp, the Sierra Nevada (5) reaches its highest elevations. Here, moraines, cirques, and small lakes and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the Ecoregion 22 is a high dissected plateau underlain by horizontal beds of limestone, sandstone, and shale, cut by canyons, and United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000. are especially common and are products of Pleistocene alpine glaciation. Large areas are above timberline, including Mt. Whitney framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Upper Neogene Stratigraphy and Tectonics of Death Valley — a Review

Earth-Science Reviews 73 (2005) 245–270 www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Upper Neogene stratigraphy and tectonics of Death Valley — a review J.R. Knott a,*, A.M. Sarna-Wojcicki b, M.N. Machette c, R.E. Klinger d aDepartment of Geological Sciences, California State University Fullerton, Fullerton, CA 92834, United States bU. S. Geological Survey, MS 975, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, CA 94025, United States cU. S. Geological Survey, MS 966, Box 25046, Denver, CO 80225-0046, United States dTechnical Service Center, U. S. Bureau of Reclamation, P. O. Box 25007, D-8530, Denver, CO 80225-0007, United States Abstract New tephrochronologic, soil-stratigraphic and radiometric-dating studies over the last 10 years have generated a robust numerical stratigraphy for Upper Neogene sedimentary deposits throughout Death Valley. Critical to this improved stratigraphy are correlated or radiometrically-dated tephra beds and tuffs that range in age from N3.58 Ma to b1.1 ka. These tephra beds and tuffs establish relations among the Upper Pliocene to Middle Pleistocene sedimentary deposits at Furnace Creek basin, Nova basin, Ubehebe–Lake Rogers basin, Copper Canyon, Artists Drive, Kit Fox Hills, and Confidence Hills. New geologic formations have been described in the Confidence Hills and at Mormon Point. This new geochronology also establishes maximum and minimum ages for Quaternary alluvial fans and Lake Manly deposits. Facies associated with the tephra beds show that ~3.3 Ma the Furnace Creek basin was a northwest–southeast-trending lake flanked by alluvial fans. This paleolake extended from the Furnace Creek to Ubehebe. Based on the new stratigraphy, the Death Valley fault system can be divided into four main fault zones: the dextral, Quaternary-age Northern Death Valley fault zone; the dextral, pre-Quaternary Furnace Creek fault zone; the oblique–normal Black Mountains fault zone; and the dextral Southern Death Valley fault zone. -

Open-File/Color For

Questions about Lake Manly’s age, extent, and source Michael N. Machette, Ralph E. Klinger, and Jeffrey R. Knott ABSTRACT extent to form more than a shallow n this paper, we grapple with the timing of Lake Manly, an inconstant lake. A search for traces of any ancient lake that inundated Death Valley in the Pleistocene upper lines [shorelines] around the slopes Iepoch. The pluvial lake(s) of Death Valley are known col- leading into Death Valley has failed to lectively as Lake Manly (Hooke, 1999), just as the term Lake reveal evidence that any considerable lake Bonneville is used for the recurring deep-water Pleistocene lake has ever existed there.” (Gale, 1914, p. in northern Utah. As with other closed basins in the western 401, as cited in Hunt and Mabey, 1966, U.S., Death Valley may have been occupied by a shallow to p. A69.) deep lake during marine oxygen-isotope stages II (Tioga glacia- So, almost 20 years after Russell’s inference of tion), IV (Tenaya glaciation), and/or VI (Tahoe glaciation), as a lake in Death Valley, the pot was just start- well as other times earlier in the Quaternary. Geomorphic ing to simmer. C arguments and uranium-series disequilibrium dating of lacus- trine tufas suggest that most prominent high-level features of RECOGNITION AND NAMING OF Lake Manly, such as shorelines, strandlines, spits, bars, and tufa LAKE MANLY H deposits, are related to marine oxygen-isotope stage VI (OIS6, In 1924, Levi Noble—who would go on to 128-180 ka), whereas other geomorphic arguments and limited have a long and distinguished career in Death radiocarbon and luminescence age determinations suggest a Valley—discovered the first evidence for a younger lake phase (OIS 2 or 4). -

Quaternary International Colonisation and Early Peopling of The

Quaternary International xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Colonisation and early peopling of the Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene and the Early Holocene: New evidence from La Serranía La Lindosa ∗ Gaspar Morcote-Ríosa, Francisco Javier Aceitunob, , José Iriartec, Mark Robinsonc, Jeison L. Chaparro-Cárdenasa a Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia b Departamento de Antropología, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia c Department of Archaeology, Exeter, University of Exeter, United Kingdom ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Recent research carried out in the Serranía La Lindosa (Department of Guaviare) provides archaeological evi- Colombian amazon dence of the colonisation of the northwest Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene. Preliminary ex- Serranía La Lindosa cavations were conducted at Cerro Azul, Limoncillos and Cerro Montoya archaeological sites in Guaviare Early peopling Department, Colombia. Contemporary dates at the three separate rock shelters establish initial colonisation of Foragers the region between ~12,600 and ~11,800 cal BP. The contexts also yielded thousands of remains of fauna, flora, Human adaptability lithic artefacts and mineral pigments, associated with extensive and spectacular rock pictographs that adorn the Rock art rock shelter walls. This article presents the first data from the region, dating the timing of colonisation, de- scribing subsistence strategies, and examines human adaptation to these transitioning landscapes. The results increase our understanding of the global expansion of human populations, enabling assessment of key inter- actions between people and the environment that appear to have lasting repercussions for one of the most important and biologically diverse ecosystems in the world. -

Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College Version June 20, 2012

1 Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College version June 20, 2012 Introduction I began accumulating this bibliography around 1996, making notes for my own uses. Since I have access to some obscure articles, I thought it might be useful to put this information where others can get at it. Comments in brackets [ ] are my own comments, opinions, and critiques, and not everyone will agree with them. The thoroughness of the annotation varies depending on when I read the piece and what my interests were at the time. The many articles from atlatl newsletters describing contests and scores are not included. I try to find news media mentions of atlatls, but many have little useful info. There are a few peripheral items, relating to topics like the dating of the introduction of the bow, archery, primitive hunting, projectile points, and skeletal anatomy. Through the kindness of Lorenz Bruchert and Bill Tate, in 2008 I inherited the articles accumulated for Bruchert’s extensive atlatl bibliography (Bruchert 2000), and have been incorporating those I did not have in mine. Many previously hard to get articles are now available on the web - see for instance postings on the Atlatl Forum at the Paleoplanet webpage http://paleoplanet69529.yuku.com/forums/26/t/WAA-Links-References.html and on the World Atlatl Association pages at http://www.worldatlatl.org/ If I know about it, I will sometimes indicate such an electronic source as well as the original citation. The articles use a variety of measurements. Some useful conversions: 1”=2.54 -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

Copyright by Emily Bradshaw Marino 2017

Copyright by Emily Bradshaw Marino 2017 The Thesis Committee for Emily Bradshaw Marino Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Isolating Lithologic Controls on Landscape Morphology in the Guadalupe Mountains, New Mexico and Texas APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Joel Johnson Paola Passalacqua David Mohrig Isolating Lithologic Controls on Landscape Morphology in the Guadalupe Mountains, New Mexico and Texas by Emily Bradshaw Marino, B.S. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Geological Sciences The University of Texas at Austin May 2017 Dedication To my loving parents, Thomas and Lucy Bradshaw, who have always supported me and encouraged me to follow my dreams. Acknowledgements First, I would like to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to my advisor, Joel Johnson, for his guidance, support, and patience throughout my time at the Jackson School. I would also like to thank my committee members, David Mohrig and Paola Passalacqua for their assistance with writing this thesis. I am grateful for the opportunities I have been given during my time at the University of Texas and I value the efforts of all the faculty and staff I have had the pleasure of working with. I am beholden to the Jackson School of Geosciences for providing support for my studies and fostering an environment of world class research and scientific study. Though my time in the field was short, I am very appreciative of the funding I received to help with my field studies and would like to thank the Jackson School and the Surface and Hydrologic Processes committee for the seed grant award. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

Welcome to the 27Th Annual Wildflower Hotline, Brought to You by the Theodore Payne Foundation, a Non-Profit Plant Nursery, Seed

Welcome back to the 28th Annual Wildflower Hotline, brought to you by the Theodore Payne Foundation, a non-profit plant nursery, seed source, book store and education center, dedicated to the preservation of wildflowers and California native plants. The glory of spring has really kicked into high gear as many deserts, canyons, parks, and natural areas are ablaze of color – so get out there and enjoy the beauty of California wildflowers. This week we begin at the Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument in Palm Desert, where the Randall Henderson and Art Smith Trails are ablaze with beavertail cactus (Opuntia basilaris), Arizona lupine (Lupinus arizonicus), little gold poppy (Eschscholzia minutiflora), chuparosa (Justicia californica), brittlebush (Encelia farinosa), desert lavender (Hyptis emoryi), wild heliotrope (Phacelia distans), and apricot mallow (Sphaeralcea ambigua). If you are heading to Palm Springs for the weekend, take a trip along Palm Canyon Dr. where the roadside is radiant with sand verbena (Abronia villosa), Fremont pincushion (Chaenactis fremontii), desert dandelion (Malacothrix glabrata), forget-me-not (Cryptantha sp.), Spanish needle (Palafoxia arida), Arizona Lupine (Lupinus arizonicus), and creosote bush (Larrea tridentata). While in the area check out Tahquitz Canyon, in the Agua Caliente Indian Reservation, off West Mesquite Ave., which is still decorated with desert dandelion (Malacothrix glabrata), pymy golden poppy (Eschscholzia minutiflora), white fiesta flower (Pholistoma membranaceum), California sun cup (Camissonia californica), brown-eyed primrose (Camissonia claviformis), and more. NOTE: This is a 2-mile loop trail that requires some scrambling over rocks. Just north of I-10, off Varner Road, Edom Hill is a carpet of color with Arizona lupine (Lupinus arizonicus), sand verbena (Abronia villosa), Fremont pincushion (Chaenactis fremontii), and croton (Croton californicus), along with a sprinkling of desert sunflower (Geraea canescens) and dyebush (Psorothamnus emoryi). -

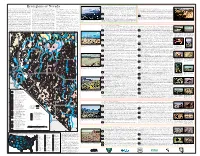

Geologic Map of the El Paso Mountains Wilderness Study Area, Kern County, California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP MF-1S27 UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE EL PASO MOUNTAINS WILDERNESS STUDY AREA, KERN COUNTY, CALIFORNIA By Brett F. Cox and Michael F. Diggles STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS age assignment is confirmed by four potassium-argon ages ranging from 15.1±0.5 m.y. to 17.9±1.6 m.y. The Black Bureau of Land Management Wilderness Study Areas Mountain Basalt is chemically distinctive, consisting of potassium-poor high-alumina basalt that is transitional The Federal Land Policy and Management Act (Public between tholeiitic basalt and alkali-olivine basalt. The basalt Law 94-579, October 21, 1976) requires the U.S. Geological was erupted mostly from east-west fissures, reflecting north- Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines to conduct mineral south extension between the Mojave Desert block and south surveys on certain areas to determine the mineral values, if western Basin and Range during early and middle Miocene any, that may be present. Results must be made available to time. the public and be submitted to the President and the The middle part of the Ricardo Formation was Congress. This report presents the results of a geologic deposited disconf ormably upon the Black Mountain Basalt and survey of the El Paso Mountains Wilderness Study Area the lower part of the Ricardo Formation during middle and (CDCA-164), California Desert Conservation Area, Kern late Miocene time. The deposits are composed of granitic County, California. and volcaniclastic detritus derived from the Mojave Desert block. Lacustrine mudstone is predominant within the area of the map but gives way to alluvial-fan sandstone and conglom ABSTRACT erate southwest of the map area.