Unit 5 A.L. Gordon and A.B. Paterson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Scottish Background of the Sydney Publishing and Bookselling

NOT MUCH ORIGINALITY ABOUT US: SCOTTISH INFLUENCES ON THE ANGUS & ROBERTSON BACKLIST Caroline Viera Jones he Scottish background of the Sydney publishing and bookselling firm of TAngus & Robertson influenced the choice of books sold in their bookshops, the kind of manuscripts commissioned and the way in which these texts were edited. David Angus and George Robertson brought fi'om Scotland an emphasis on recognising and fostering a quality homegrown product whilst keeping abreast of the London tradition. This prompted them to publish Australian authors as well as to appreciate a British literary canon and to supply titles from it. Indeed, whilst embracing his new homeland, George Robertson's backlist of sentimental nationalistic texts was partly grounded in the novels and verse written and compiled by Sir Walter Scott, Robert Bums and the border balladists. Although their backlist was eclectic, the strong Scottish tradition of publishing literary journals, encyclopaedias and religious titles led Angus & Robertson, 'as a Scotch firm' to produce numerous titles for the Presbyterian Church, two volumes of the Australian Encyclopaedia and to commission writers from journals such as the Bulletin. 1 As agent to the public and university libraries, bookseller, publisher and Book Club owner, the firm was influential in selecting primary sources for the colony of New South Wales, supplying reading material for its Public Library and fulfilling the public's educational and literary needs. 2 The books which the firm published for the See Rebecca Wiley, 'Reminiscences of George Robertson and Angus & Robertson Ltd., 1894-1938' ( 1945), unpublished manuscript, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, ML MSS 5238. -

Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1)

Australian Capital Territory Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Disallowable instrument DI2013-228 made under the Public Place Names Act 1989 — section 3 (Minister to determine names) I DETERMINE the names of the public places that are Territory land as specified in the attached schedule and as indicated on the associated plan. Ben Ponton Delegate of the Minister 04 September 2013 Page 1 of 7 Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au SCHEDULE Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Division of Lawson: Henry Lawson’s Australia NAME ORIGIN SIGNIFICANCE Bellbird Loop Crested Bellbird ‘Bellbird’ is a name given in Australia to two endemic (Oreoica gutturalis) species of birds, the Crested Bellbird and the Bell-Miner. The distinctive call of the birds suggests Bell- Miner the chiming of a bell. Henry Kendall’s poem Bell Birds (Manorina was first published in Leaves from Australian Forests in melanophrys) 1869: And, softer than slumber, and sweeter than singing, The notes of the bell-birds are running and ringing. The silver-voiced bell-birds, the darlings of day-time! They sing in September their songs of the May-time; Billabong Street Word A ‘billabong’ is a pool or lagoon left behind in a river or in a branch of a river when the water flow ceases. The Billabong word is believed to have derived from the Indigenous Wiradjuri language from south-western New South Wales. The word occurs frequently in Australian folk songs, ballads, poetry and fiction. -

September 2005 Page 105 Page 108 Page

September 2005 VOL.2 | ISSUE 3 Nebula ISSN-1449 7751 A JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY SCHOLARSHIP DEAD SOULS TARGET TIME'S GREATLAND DIRECTION Adam King Jennifer David Carithers Thompson Page 105 Page 108 Page 127 Nebula 2.3, September 2005 The Nebula Editorial Board Dr. Samar Habib: Editor in Chief (Australia) Dr. Joseph Benjamin Afful, University of Cape Coast (Ghana) Dr. Senayon S. Alaoluw,University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa) Dr. Samirah Alkasim, independent scholar (Egypt) Dr. Rebecca Beirne, The University of Newcastle (Australia) Dr. Nejmeh Khalil-Habib, The University of Sydney (Australia) Dr. Isaac Kamola, Dartmouth College (U.S.A) Garnet Kindervater, The University of Minnesota (U.S.A) Dr. Olukoya Ogen, Obafemi Awolowo University (Nigeria) Dr. Paul Ayodele Osifodunrin, University of Lagos (Nigeria) Dr. Babak Rahimi, University of California (San Diego, U.S.A) Dr. Michael Angelo Tata, City University of New York (U.S.A) The Nebula Advisory Board Dr. Serena Anderlini-D’Onofrio, The University of Puerto Rico Dr. Paul Allatson, The University of Technology, Sydney (Australia) Dr. Benjamin Carson, Bridgewater State College (U.S.A) Dr. Murat Cemrek, Selcuk University (Turkey) Dr. Melissa Hardie, The University of Sydney (Australia) Dr. Samvel Jeshmaridian, The City University of New York (U.S.A) Dr. Christopher Kelen, The University of Macao (China) Dr. Kate Lilley, The University of Sydney (Australia) Dr. Karmen MacKendrick, Le Moyne College of New York (U.S.A) Dr. Tracy Biga MacLean, Academic Director, Claremont Colleges (U.S.A) Dr. Wayne Pickard, a very independent scholar (Australia) Dr. Ruying Qi, The University of Western Sydney (Australia) Dr. -

Whatever Season Reigns

Whatever Season Reigns... Reflection Statement 24 Whatever Season Reigns... 25 In primary school I discovered “Land of the Rainbow Gold”, a collection of Classic Australian Bush Poetry compiled by Mildred M Fowler. As a child growing up in the homogenised landscape of suburban Australia I was captured by the romantic notion of Australia’s bush heritage. It was a national identity seeded in our rural beginnings; and much like Banjo Patterson wistful musings I always rather fancied I’d like to “change with Clancy, like to take a turn at droving where the seasons come and go”1; Many seasons later I returned to these poems for inspiration for my major work “Whatever Season Reigns...”2 On revisiting the works of writers such as Paterson and Lawson I was struck with how little I actually shared with these voices that were deemed to have forged Australia’s “literary legend” and our national identity3. The Australian narrative was one shaped by male experiences. There was no room for women. Only the token “drovers wife”4 or “army lass”5 proved anomalous to the trend but were not afforded the same complexity as their male counterparts. According to Kijas “Despite their invisibility in much nationalist and historical narrative, women in their diversity have been active historical protagonists across outback landscapes.” 6My work, appropriating the short 1 Paterson, AB. “Clancy of The Overflow.” Land Of The Rainbow Gold. Ed. Fowler, Mildred M. Melbourne: Thomas Nelson, 1967. Print. 2 Moore, JS. (1864) Spring Life - Lyrics. Sydney: Reading and Wellbank. 3 Simon, C. (2014). Banjo Paterson: is he still the bard of the bush?. -

49Th Country Music Awards Of

49th Country Music Awards of Australia 2021 Toyota Golden Guitar Awards Handbook 49th Country Music Awards of Australia AWARDS HANDBOOK Contents 1. ENTRY DATES ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 2. GENERAL TERMS & CONDITIONS .............................................................................................................................. 2 3. CURRENT ELIGIBILITY PERIOD ................................................................................................................................... 3 4. DEFINITIONS ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 5. ALBUM CATEGORY REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................................................................ 4 6. CATEGORIES & ELIGIBILITY ....................................................................................................................................... 5 A TOYOTA ALBUM OF THE YEAR ................................................................................................................. 5 B ALT COUNTRY ALBUM OF THE YEAR ........................................................................................................ 5 C CONTEMPORARY COUNTRY ALBUM OF THE YEAR .................................................................................. 6 D TRADITIONAL COUNTRY -

Henry Lawson and the Salvation Army – Stuart Devenish

Vol. 2 No. 1 (November 2009) Henry Lawson and the Salvation Army – Stuart Devenish. On February 19, 2009 Salvation Army Major Bob Broadbere (retired) presented a lecture entitled 'Henry Lawson and his place in Salvation Army History' to an audience of approximately 70 people, mainly Salvation Army officers and soldiers at the Salvation Army’s Booth College campus at Bexley North, Sydney. The connection between Lawson and the Salvation Army has held an enduring fascination for Broadbere who has amassed a comprehensive personal library on Henry Lawson and his association with the Salvation Army. Having corresponded with the late Prof. Colin Roderick (editor of the 3 volume Henry Lawson, Collected Verse, A & R, Sydney, 1966-8) Broadbere is something of a specialist in the field. His interest in Henry Lawson sprang to life when Broadbere himself lived and worked in the St Leonards-North Sydney areas where Lawson had lived. Permission was obtained from Major Bob Broadbere to reproduce here some of his research as presented in his lecture. The ‘Army’ in Lawson’s Poetry The connection between Henry Lawson and the Salvation Army remains largely unknown in any of the contexts relevant to it, e.g., the Salvation Army, the Christian community, or the wider Australian population. In part this is because writers such as Banjo Paterson and Henry Lawson are not so well known nor so carefully read as they once were. Our understanding of the connection between Lawson and the Salvation Army is not helped by the oblique nature of Lawson’s writing about the Army. According to private correspondence between Roderick and Broadbere, Lawson never threw himself on the mercies of the Army despite his alcoholism and illness later in life. -

World Music Reference

The Music Studio http://www.themusicstudio.ca [email protected] 416.234.9268 World Music Reference Welcome to The Music Studio’s World Music Reference! This is meant to be a brief introduction to the greater world of musical styles found in cultures around the globe. This is only the smallest sampling of the incredible forms of music that can be found once you leave the comfort of your own playlist! Dive in, explore, and find a style of music that speaks to you in a way might never have heard otherwise! North America Blues https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N-KluFB9A8M The Blues is a genre and form of music that started out in the Deep South of the United States sometime around the 1870s. It was created by African Americans from roots in African musical traditions, African American work songs, and spirituals – an oral tradition that imparted Christian values while also describing the terrible hardships of slavery. Early blues often took the form of a loose story or narrative, usually relating to the discrimination and other hardships African Americans faced. The Blues form, which is now found throughout jazz, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll, is characterized by a call-and-response pattern, the blues scales, and specific song structure – of which, the 12-bar blues has become the most common. The Blues is also characterized by its lamenting lyrics, distinctive bass lines, and unique instrumentation. The earliest traditional blues verses used a single line repeated four times. It wouldn’t be until the early part of the 20th century that the most common blues structure currently used became standard: the AAB pattern. -

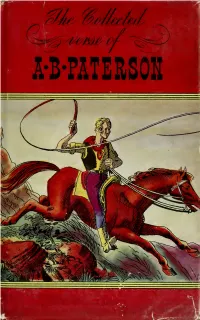

The Collected Verse of A.B. Paterson : Containing the Man from Snowy

The Collected Verse of A.B. ^^ Banjo^^ Paterson First published in 1921, The Collected Verse of A. B. Paterson has won and held a large and varied audience. Since the appearance of The Man from Snoiuy River in 1895, bushman and city dweller alike have made immediate response to the swinging rhythms of these inimitable tales in verse, tales that reflect the essential Australia. The bush ballad, brought to its perfection by Paterson, is the most characteristic feature of Australian literature. Even Gordon produced no better racing verse than "The Ama- teur Rider"' and "Old Pardon, the Son of Reprieve"; nor has the humour of "A Bush Christening" or "The Man from Ironbark" yet been out- shone. With their simplicity of form and flowing movement, their adventu- rous sparkle and careless vigour, Paterson's ballads stand for some- thing authentic and infinitely preci- ous in the Australian tradition. They stand for a cheerful and carefree attitude, a courageous sincerity that apart from is all too rare today. And, the humour and lifelikeness and ex- citement of his verse, Paterson sees kRNS and feels the beauty of the Australian landscape and interprets it so sponta- neously that no effort of art is ap- parent. In this he is the poet as well as the story-teller in verse. With their tales of bush life and adventure, their humour and irony "Banjo" Paterson's ballads are as fresh today as they ever were. (CoiUinued on back flap) "^il^ \v> C/H-tAM ) l/^c^ TUFTS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES nil 3 9090 014 556 118 THE COLLECTED VERSE of A. -

The Man from Snowy River and Other Verses

The Man From Snowy River and Other Verses Paterson, Andrew Barton (1864-1941) University of Sydney Library Sydney 1997 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ © Copyright for this electronic version of the text belongs to the University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: The Man From Snowy River and Other Verses Andrew Barton Paterson Angus and Robertson Sydney 1917 Includes a preface by Rolf Boldrewood Scanned text file available at Project Gutenberg, prepared by Alan R.Light. Encoding of the text file at was prepared against first edition of 1896, including page references and other features of that work. All quotation marks retained as data. All unambiguous end-of-line hyphens have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. Author First Published 1895 Australian Etexts 1910-1939 poetry verse Portrait photograph: A.B. Paterson Preface Rolf Boldrewood It is not so easy to write ballads descriptive of the bushland of Australia as on light consideration would appear. Reasonably good verse on the subject has been supplied in sufficient quantity. But the maker of folksongs for our newborn nation requires a somewhat rare combination of gifts and experiences. Dowered with the poet's heart, he must yet have passed his ‘wander-jaehre’ amid the stern solitude of the Austral waste — must have ridden the race in the back-block township, guided the reckless stock-horse adown the mountain spur, and followed the night- long moving, spectral-seeming herd ‘in the droving days’. -

VOL 22.1 NEWSLETTER of February 2011 – March 2011 the ADELAIDE COUNTRY MUSIC CLUB INC

COUNTRY CALL VOL 22.1 NEWSLETTER OF February 2011 – March 2011 THE ADELAIDE COUNTRY MUSIC CLUB INC. www.acmc.org.au Club Patron …Trev Warner WITH CO-OPERATION FROM THE SLOVENIAN CLUB THE ADELAIDE COUNTRY MUSIC CLUB INC. PRESENTS SUNDAY February 6th 2011 - show 12.30 to 4.30pm DOORS OPEN 11.00 am 22nd Birthday Show Craig Giles backed by the Blackhats Catering will be available 12 noon – 2pm Sandwiches - Cakes - Fruit Plates Entry:- ACMC members and other Country Music Club Members:- $5.00 all others $7.00 SUNDAY March 6th 2011 – Show 12.30 to 4.30pm DOORS OPEN 11.00 am Heartland plus Graeme Hugo Catering will be available 12 noon – 2pm Sandwiches - Cakes - Fruit Plates Entry:- ACMC and other Country Music Club Members:- $5.00 all others $7.00 Coming Attractions Norma O’Hara Murphy backed by Apr 3 2011 May 1 2011 Ian List and his Sidekicks Bernie & the Bandits June 5 2011 Brian Letton with Cactus Martens July 3 2011 City Cowboys + Billy Dee AGM and Charlie McCracken and Aug 7 2011 Sept 4 2011 Kindred Spirit band President’s Report Hi everyone Happy New Year to you all. Here we go with another exciting year of great music and fun at our club. It’s our 22nd birthday in February and that’s exciting on its own. Come and help us celebrate. Our band of the day will be Craig Giles backed by the Blackhats. It should be a great show. Don’t forget for some at our venue who don’t dance it gets cold with the air conditioner on so bring a jacket or cardigan. -

'Banjo' Paterson and an Irish Racing Connection

Australia’s Bard, ‘Banjo’ Paterson and an Irish Racing Connection By James Robinson M. Phil. Andrew Barton Paterson, through his writings, has come to symbolize the Australian outback. His poetry, ballads and novels reflect the spirit of rural Australia. The vast distances, the harsh climate and the beauty of the landscape are the background to his stories, which invariably reference horses. Paterson’s characters never give in, but endure with stoic determination and laconic humour to survive and often succeed. Banjo Paterson loved horses and horseracing and was himself an accomplished horseman and student of horse breeding. His best known works include ‘The Man from Snowy River’, ‘Clancy of the Overflow’ and inevitably ‘Waltzing Matilda’. The latter is known worldwide as the unofficial anthem of Australia. This paper references his life and times and an Irish racing connection - The Kennedys of Bishopscourt, Kill, Co. Kildare. Born on February 17 1864 at Narrambla, near Orange, New South Wales, A. B. Paterson was the eldest of seven children born to Andrew Bogle Paterson (1833-1889), a Scottish migrant who married Rose Isabella Barton (1844-1903), a native born Australian. ‘Barty’, as he was known to family and friends, enjoyed a bush upbringing. When he was seven, the family moved to Illalong in the Lachlan district. There, the family took over a farm on the death of his uncle, John Paterson, who had married his mother’s sister, Emily Susanna Barton. Here, near the main route between Sydney and Melbourne, the young Paterson saw the kaleidoscope of busy rural life. Coaches, drovers, gold escorts and bullock teams together with picnic race meetings and polo matches were experiences which formed the basis for his famous ballads. -

September 2019 Newsletter

TSA ‘’First the Song’’ President’s Report In this edition: Hi all members and friends of the TSA, President’s Report So far so good for 2019 with a great start at the January TCMF and TSA members having opportunities to perform after the TCMF at Bonnie Doon, Blue Water fes- TSA Song Comp RULES tival and Hats Off in July where we had 20 members playing over the three days. 2019 TSA Song Sessions All these opportunities provided by hard work and organising by Lydia Clare. We have also seen TSA members do well in the International Songwriting Competi- @ Hats Off Pics tion, Songs Alive Australia and hopefully in the ASA results coming up soon. Songwriting competitions are a wonderful way of testing your skill against others and we encourage you also support our sister organisations the ASA and Song- MEMBERS NEWS sAlive Australia as we all have something different to offer. Indeed, the TSA and • Kathryn Luxford songs Alive! Australia will combine to present a Songwriting WORKSHOP IN THE BLUE MOUNTAINS 14th- 15th September. This is a really good, short hard-working • Col Thomson workshop with plenty of performing, songwriting and networking. Details in this newsletter and there are some spots left. • Shelley Jones Band Planning for the 202 TCMF is well underway with the TSA Songwriting Competi- • Trinity Woodhouse tion open from 1st August entries www.tsa.songcentral.biz so get yourself to the workshop , write that song and enter the TSA Songwriting Competition. Blue Mountains Song- Our performance opportunities in Tamworth in 2020 will be centred at the Tam- writing workshop - worth City Bowling Club with Mini- Concerts, Talent Quest mornings and the September 14-15, 2019 Showcases afternoons.