'Banjo' Paterson and an Irish Racing Connection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Killeen Castle and Estate Being Turned Into Major Hotel and Golf Resort Consulting Engineers: Barrett Mahony, Dublin

ACEI_07-p69-110 3/1/07 10:22 AM Page 91 ACEI Killeen Castle and estate being turned into major hotel and golf resort Consulting engineers: Barrett Mahony, Dublin Killeen Castle, an historic residence in Co Meath, long derelict, is being totally restored in a long term project that will see the castle form the basis of a five star luxury hotel, the creation of a top class 18 hole golf course and the building of 179 luxury houses. Already, the resort has been selected as the venue in 2011 of the Solheim Cup, when the best female golfers in Europe will compete against their opposite numbers from the US. It’s a biennial competition that is the female equivalent of the Ryder Cup. For the Killeen Castle project, it’s a huge vote of confidence, before the project is even finished.When this com- petition was held in Sweden in 2003, it attracted over 100,000 spectators, so when the Solheim Cup competition comes to Killeen Castle, it is likely to prove just as popular draw for visitors as the Ryder Cup was at the K Club in September, 2006. The Killeen demesne was the ancestral home of the Plunkett family for close on 600 years; St Oliver Plunkett was a member of this distinguished family. The demesne of Killeen was created in 1181 by explaining why even today, the Killeen estate is much Hugh de Lacy. Sir Christopher Plunkett, deputy Lord larger than its next door neighbour. Lieutenant of Ireland, was created the Baron of Killeen in the early 15th century; he had married the The original Norman keep at Killeen was built in the daughter of Sir Lucas Cusack in 1403, thereby bring- 12th century and subsequently, various extensions ing the demesnes of both Killeen and neighbouring were built before it fell into ruin. -

Activities at the K Club.Pdf

While at The K Club, why not make the most of your stay and enjoy the range of activities we have on offer. From quiet fishing to energetic horse-riding we have a whole host of family friendly activities to suit everyone. www.kclub.ie Welcome €125.00 per adult for 3 hours €15.00 for each additional hour (Max 3 people per Ghillie, inclusive of all required Fishing at The K Club is mostly for Brown Trout and Rainbow Trout with the equipment) occasional Pike or Perch also. Fishing is carried out from the bank of the lakes Seasons Dates for Lakes Fishing and is done with a spinning rod and artificial bait or by Fly Rod and artificial flies. The group are accompanied by a ghillie (Fishing Guide) throughout the Brown Trout March 1st to September 30th session who will advise and demonstrate the art of casting and the placing of Rainbow Trout All year round baits in the correct manner so that a fish may be caught. All fish are returned alive to the water or if the guests wish may be brought to the kitchen and cooked Pike All year round to their requirements if so desired. Fishing €80.00 per adult / €55.00 per child for 2 hours Kayaking is now available on our private mile-long stretch of the beautiful river Liffey. If you have never kayaked before, you are in for a real treat, particularly as the river is so beautiful and peaceful here in the demesne. Our friendly and helpful instructors will provide wetsuits and an introduction to kayaking if needed before you set off for the afternoon. -

Issue Id: 2011/B/56 Annual Returns Received Between 25-Nov-2011 and 01-Dec-2011 Index of Submission Types

ISSUE ID: 2011/B/56 ANNUAL RETURNS RECEIVED BETWEEN 25-NOV-2011 AND 01-DEC-2011 INDEX OF SUBMISSION TYPES B1B - REPLACEMENT ANNUAL RETURN B1C - ANNUAL RETURN - GENERAL B1AU - B1 WITH AUDITORS REPORT B1 - ANNUAL RETURN - NO ACCOUNTS CRO GAZETTE, FRIDAY, 02nd December 2011 3 ANNUAL RETURNS RECEIVED BETWEEN 25-NOV-2011 AND 01-DEC-2011 Company Company Documen Date Of Company Company Documen Date Of Number Name t Receipt Number Name t Receipt 2152 CLEVELAND INVESTMENTS B1AU 28/10/2011 19862 STRAND COURT LIMITED B1C 28/10/2011 2863 HENRY LYONS & COMPANY, LIMITED B1C 25/11/2011 20144 CROWE ENGINEERING LIMITED B1C 01/12/2011 3394 CARRIGMAY LIMERICK, B1AU 28/10/2011 20474 AUTOMATION TRANSPORT LIMITED B1C 28/10/2011 3577 UNITED ARTS CLUB, DUBLIN, LIMITED B1C 28/10/2011 20667 WEXFORD CREAMERY LIMITED B1C 24/11/2011 7246 VALERO ENERGY (IRELAND) LIMITED B1C 21/10/2011 20769 CHERRYFIELD COURTS LIMITED B1C 28/10/2011 7379 RICHARD DUGGAN AND SONS, LIMITED B1C 26/10/2011 20992 PARK DEVELOPMENTS (IRELAND) B1C 28/10/2011 7480 BEWLEY'S CAFÉ GRAFTON STREET B1C 27/10/2011 LIMITED LIMITED 21070 WESTFIELD INVESTMENTS B1AU 28/10/2011 7606 ST. VINCENT'S PRIVATE HOSPITAL B1C 28/11/2011 21126 COMMERCIAL INVESTMENTS LIMITED B1C 24/10/2011 LIMITED 21199 PARK DEVELOPMENTS (1975) LIMITED B1C 28/10/2011 7662 THOMAS BURGESS & SONS LIMITED B1C 18/11/2011 21351 BARRAVALLY LIMITED B1C 28/10/2011 7857 J. H. DONNELLY (HOLDINGS) LIMITED B1C 28/10/2011 22070 CABOUL LIMITED B1C 28/10/2011 8644 CARRIGMAY B1C 28/10/2011 22242 ARKLOW HOLIDAYS LIMITED B1C 28/10/2011 9215 AER LINGUS LIMITED B1C 27/10/2011 22248 OGILVY & MATHER GROUP LIMITED B1C 28/10/2011 9937 D. -

Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1)

Australian Capital Territory Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Disallowable instrument DI2013-228 made under the Public Place Names Act 1989 — section 3 (Minister to determine names) I DETERMINE the names of the public places that are Territory land as specified in the attached schedule and as indicated on the associated plan. Ben Ponton Delegate of the Minister 04 September 2013 Page 1 of 7 Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au SCHEDULE Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Division of Lawson: Henry Lawson’s Australia NAME ORIGIN SIGNIFICANCE Bellbird Loop Crested Bellbird ‘Bellbird’ is a name given in Australia to two endemic (Oreoica gutturalis) species of birds, the Crested Bellbird and the Bell-Miner. The distinctive call of the birds suggests Bell- Miner the chiming of a bell. Henry Kendall’s poem Bell Birds (Manorina was first published in Leaves from Australian Forests in melanophrys) 1869: And, softer than slumber, and sweeter than singing, The notes of the bell-birds are running and ringing. The silver-voiced bell-birds, the darlings of day-time! They sing in September their songs of the May-time; Billabong Street Word A ‘billabong’ is a pool or lagoon left behind in a river or in a branch of a river when the water flow ceases. The Billabong word is believed to have derived from the Indigenous Wiradjuri language from south-western New South Wales. The word occurs frequently in Australian folk songs, ballads, poetry and fiction. -

Whatever Season Reigns

Whatever Season Reigns... Reflection Statement 24 Whatever Season Reigns... 25 In primary school I discovered “Land of the Rainbow Gold”, a collection of Classic Australian Bush Poetry compiled by Mildred M Fowler. As a child growing up in the homogenised landscape of suburban Australia I was captured by the romantic notion of Australia’s bush heritage. It was a national identity seeded in our rural beginnings; and much like Banjo Patterson wistful musings I always rather fancied I’d like to “change with Clancy, like to take a turn at droving where the seasons come and go”1; Many seasons later I returned to these poems for inspiration for my major work “Whatever Season Reigns...”2 On revisiting the works of writers such as Paterson and Lawson I was struck with how little I actually shared with these voices that were deemed to have forged Australia’s “literary legend” and our national identity3. The Australian narrative was one shaped by male experiences. There was no room for women. Only the token “drovers wife”4 or “army lass”5 proved anomalous to the trend but were not afforded the same complexity as their male counterparts. According to Kijas “Despite their invisibility in much nationalist and historical narrative, women in their diversity have been active historical protagonists across outback landscapes.” 6My work, appropriating the short 1 Paterson, AB. “Clancy of The Overflow.” Land Of The Rainbow Gold. Ed. Fowler, Mildred M. Melbourne: Thomas Nelson, 1967. Print. 2 Moore, JS. (1864) Spring Life - Lyrics. Sydney: Reading and Wellbank. 3 Simon, C. (2014). Banjo Paterson: is he still the bard of the bush?. -

Hide and Seek with Windows Shuttered and Corridors Empty for the First Six Months of the Year, Many Hotels Have Taken the Time to Re-Evaluate, Refresh and Rejuvenate

TRAVEL THE CLIFF AT LYONS Hide and Seek With windows shuttered and corridors empty for the first six months of the year, many hotels have taken the time to re-evaluate, refresh and rejuvenate. Jessie Collins picks just some of the most exciting new experiences to indulge in this summer. THE CLIFF AT LYONS What’s new Insider Tip Aimsir is upping its focus on its own garden produce, Cliff at Lyons guest rooms are all individually designed Best-loved for which is also to be used in the kitchens under the eye of and spread out between a selection of historic buildings Its laid-back luxurious feel and the fastest ever UK and former Aimsir chef de partie and now gardener, Tom that give you that taste of country life while maintaining Ireland two-star ranked Michelin restaurant, Aimsir. Downes, and his partner Stina. Over the summer, a new all the benefits of a luxury hotel. But there is also a There are award-winning spa treatments to be had at orchard will be introduced, along with a wild meadow selection of pet-friendly rooms if you fancy taking your The Well in the Garden, and with its gorgeous outdoor and additional vegetable beds which will be supplying pooch with you. Also don’t forget the Paddle and Picnic spaces, local history, canal walks, bike rides and paddle- the Cliff at Lyons restaurants. Chicken coops, pigs and package which gives you a one-night B&B stay plus SUP boarding there’s plenty to do. Sean Smith’s fresh take even beehives are also to be added, with the aim of session, and a picnic from their pantry, from €245 for two on classic Irish cuisine in The Mill has been a great bringing the Cliff at Lyons closer to self-sustainability. -

April 4-6 Contents

MEDIA GUIDE #TheWorldIsWatching APRIL 4-6 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S WELCOME 3 2018 WINNING OWNER 50 ORDER OF RUNNING 4 SUCCESSFUL OWNERS 53 RANDOX HEALTH GRAND NATIONAL FESTIVAL 5 OVERSEAS INTEREST 62 SPONSOR’S WELCOME 8 GRAND NATIONAL TIMELINE 64 WELFARE & SAFETY 10 RACE CONDITIONS 73 UNIQUE RACE & GLOBAL PHENOMENON 13 TRAINERS & JOCKEYS 75 RANDOX HEALTH GRAND NATIONAL ANNIVERSARIES 15 PAST RESULTS 77 ROLL OF HONOUR 16 COURSE MAP 96 WARTIME WINNERS 20 RACE REPORTS 2018-2015 21 2018 WINNING JOCKEY 29 AINTREE JOCKEY RECORDS 32 RACECOURSE RETIRED JOCKEYS 35 THIS IS AN INTERACTIVE PDF MEDIA GUIDE, CLICK ON THE LINKS TO GO TO THE RELEVANT WEB AND SOCIAL MEDIA PAGES, AND ON THE GREATEST GRAND NATIONAL TRAINERS 37 CHAPTER HEADINGS TO TAKE YOU INTO THE GUIDE. IRISH-TRAINED WINNERS 40 THEJOCKEYCLUB.CO.UK/AINTREE TRAINER FACTS 42 t @AINTREERACES f @AINTREE 2018 WINNING TRAINER 43 I @AINTREERACECOURSE TRAINER RECORDS 45 CREATED BY RACENEWS.CO.UK AND TWOBIRD.CO.UK 3 CONTENTS As April approaches, the team at Aintree quicken the build-up towards the three-day Randox Health Grand National Festival. Our first port of call ahead of the 2019 Randox welfare. We are proud to be at the forefront of Health Grand National was a media visit in the racing industry in all these areas. December, the week of the Becher Chase over 2019 will also be the third year of our the Grand National fences, to the yard of the broadcasting agreement with ITV. We have been fantastically successful Gordon Elliott to see delighted with their output and viewing figures, last year’s winner Tiger Roll being put through not only in the UK and Ireland, but throughout his paces. -

Henry Lawson and the Salvation Army – Stuart Devenish

Vol. 2 No. 1 (November 2009) Henry Lawson and the Salvation Army – Stuart Devenish. On February 19, 2009 Salvation Army Major Bob Broadbere (retired) presented a lecture entitled 'Henry Lawson and his place in Salvation Army History' to an audience of approximately 70 people, mainly Salvation Army officers and soldiers at the Salvation Army’s Booth College campus at Bexley North, Sydney. The connection between Lawson and the Salvation Army has held an enduring fascination for Broadbere who has amassed a comprehensive personal library on Henry Lawson and his association with the Salvation Army. Having corresponded with the late Prof. Colin Roderick (editor of the 3 volume Henry Lawson, Collected Verse, A & R, Sydney, 1966-8) Broadbere is something of a specialist in the field. His interest in Henry Lawson sprang to life when Broadbere himself lived and worked in the St Leonards-North Sydney areas where Lawson had lived. Permission was obtained from Major Bob Broadbere to reproduce here some of his research as presented in his lecture. The ‘Army’ in Lawson’s Poetry The connection between Henry Lawson and the Salvation Army remains largely unknown in any of the contexts relevant to it, e.g., the Salvation Army, the Christian community, or the wider Australian population. In part this is because writers such as Banjo Paterson and Henry Lawson are not so well known nor so carefully read as they once were. Our understanding of the connection between Lawson and the Salvation Army is not helped by the oblique nature of Lawson’s writing about the Army. According to private correspondence between Roderick and Broadbere, Lawson never threw himself on the mercies of the Army despite his alcoholism and illness later in life. -

7 Day Luxury Itinerary for South of Island 7 Day Luxury Itinerary for South of Island

7 Day Luxury Itinerary for South of Island 7 Day Luxury Itinerary for South of Island DAY 1: Step into Ireland’s Ancient East... DUBLIN DAA PLATINUM SERVCIES RUSSBOROUGH HOUSE - Private Tour, Birds of Prey & Artisans of Russborough Tel: +353 (0) 1 8144895 www.dublinairport.com/at-the-airport/travel-services/ Tel: +353 (0) 45865239 / www.russborough.ie platinum-services Visit this award winning house with it’s ornate, 18th-century Step off your flight to a luxury, fast, effortless travel experience Palladian villa with collections of porcelain, furniture and art with a warm Irish welcome. Meet your private luxury Chauffeur masterpieces, before visiting the National Birds of Prey Centre to service before fast tracking through priority immigration to meet over 40 different Birds of Prey. platinum services private terminal. Enjoy a Hawk Walk while learning how to handle these great birds. Enjoy some relaxation and refreshment time in your private Meet the centre’s Magnificent Eagle, against the backdrop of suite with shower facilities and clothing valet services available, the spectacular Wicklow Mountains, before browsing the studios as well as porter assistance for luggage reclaim so you feel of the Mastercraftsman, The Artisans of Russborrough in the refreshed and ready to get the most from every moment of refurbished stable yard of the Estate. your trip to Ireland. Powerscourt House & Gardens – Russborough ( 41 km/ 56 mins) POWERSCOURT ESTATE PRIVATE HOUSE & GARDEN TOUR WITH BRUNCH WILD FOOD FORAGING WITH BLACKSTAIRS ECO TRAILS Tel: + 353 (0) 1 204 6000 / www.powerscourt.com Tel: +353 (0)87 270 71 89 / www.blackstairsecotrails.ie Enjoy a ‘Behind the Scenes’ private tour of Powerscourt House and Gardens with the Estate family. -

The Birr Castle Retreat And

© Copyright TREDIC Corporation 2018 irish birr capital limited A TREDIC Corporation project SPV The Birr Castle Retreat and Spa Securing and persevering the Birr Estate for the next generation A corporate stakeholder introduction to the Birr Castle Estate and the Birr Castle Retreat and Spa project. Q4 2018 Image © copyright Schletterer Consult GmbH CORPORATION TREDIC Corporation Tel: +44 (0) 208 849 5646 Fax: +44 (0) 208 899 6001 Building 3, Chiswick Park, 566 Chiswick High Road, Chiswick, Email: [email protected] London W4 5YA, United Kingdom. Web: www.trediccorporation.com www.trediccorporation.com © Copyright TREDIC Corporation 2018 irish Oxmantown Settlement Trust birr capital Birr Scientific and Heritage Foundation limited Hello, and welcome to our presentation. I warmly welcome our Stakeholder Groups, and I look forward to presenting our vision for the future of the Birr Castle Estate to you in this information memorandum. Birr, like so many other magnificent country estates in the U.K. and Ireland, proves extremely expensive to preserve, to maintain and to run on day to day basis. Successful efforts have been made to date to ensure revenue is being generated through the estate to cover our basic cash flow requirements. To date, increasing annual visitors to the estate, a thriving museum and science centre, the development of the LOFAR Programme within the grounds, a retail shop with growing sales, and one of the most successful food and beverage offerings in Birr are all testament to the progress that continues to be made. -

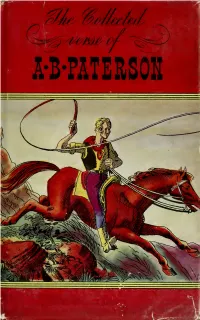

The Collected Verse of A.B. Paterson : Containing the Man from Snowy

The Collected Verse of A.B. ^^ Banjo^^ Paterson First published in 1921, The Collected Verse of A. B. Paterson has won and held a large and varied audience. Since the appearance of The Man from Snoiuy River in 1895, bushman and city dweller alike have made immediate response to the swinging rhythms of these inimitable tales in verse, tales that reflect the essential Australia. The bush ballad, brought to its perfection by Paterson, is the most characteristic feature of Australian literature. Even Gordon produced no better racing verse than "The Ama- teur Rider"' and "Old Pardon, the Son of Reprieve"; nor has the humour of "A Bush Christening" or "The Man from Ironbark" yet been out- shone. With their simplicity of form and flowing movement, their adventu- rous sparkle and careless vigour, Paterson's ballads stand for some- thing authentic and infinitely preci- ous in the Australian tradition. They stand for a cheerful and carefree attitude, a courageous sincerity that apart from is all too rare today. And, the humour and lifelikeness and ex- citement of his verse, Paterson sees kRNS and feels the beauty of the Australian landscape and interprets it so sponta- neously that no effort of art is ap- parent. In this he is the poet as well as the story-teller in verse. With their tales of bush life and adventure, their humour and irony "Banjo" Paterson's ballads are as fresh today as they ever were. (CoiUinued on back flap) "^il^ \v> C/H-tAM ) l/^c^ TUFTS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES nil 3 9090 014 556 118 THE COLLECTED VERSE of A. -

Barton Stud Back in Premier Fray Cont

MONDAY, 26 AUGUST 2019 SKITTER SCATTER RETURNS THURSDAY BARTON STUD BACK Last year=s G1 Moyglare Stud S. winner and Cartier champion IN PREMIER FRAY 2-year-old filly Skitter Scatter (Scat Daddy) is set to return from a four-month absence in Thursday=s G3 Fairy Bridge S. at Tipperary. Anthony and Sonia Rogers=s filly was last seen beating just one home on seasonal debut in the G1 1000 Guineas, after which it was revealed she had torn a muscle. Patrick Prendergast handled Skitter Scatter=s career at two before this year turning in his license but joining up with her new trainer John Oxx. Prendergast said on Sunday, "Hopefully we get a bit more of this nice weather that is forecast and so long as the ground is nice, she's going to run in Tipperary, all being well. It does seem a long time since the Guineas. It's been frustrating, but these things take time and just require a bit of patience. She seems happy and well and we're looking forward to getting her back on the track." Cont. p4 Barton Stud=s Tom Blain | Laura Green By Emma Berry IN TDN AMERICA TODAY As an operation on the outskirts of Newmarket about to THE WEEK IN REVIEW: RACING AT ITS BEST celebrate its centenary, it's only natural that Barton Stud has a Bill Finley takes a look back at last weekend’s racing action, long history of consigning locally at Tattersalls, but it dipped a including a superlative renewal of the GI Personal Ensign, won by toe in the Doncaster waters last August and found them Midnight Bisou.