The Scottish Background of the Sydney Publishing and Bookselling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inaugural Speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith

Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author would like to thank officers from both Houses for their comments on a draft of this paper, in particular Stephanie Hesford and Jonathan Elliott from the Legislative Assembly and Stephen Frappell and Samuel Griffith from the Legislative Council. Thanks, too, to Lenny Roth and Greig Tillotson for their comments and advice. Any errors are the author’s responsibility. ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 978 0 7313 1900 8 May 2013 © 2013 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior consent from the Manager, NSW Parliamentary Research Service, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament by Gareth Griffith NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Manager, Politics & Government/Law .......................................... (02) 9230 2356 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Acting Senior Research Officer, Law ............................................ (02) 9230 3085 Lynsey Blayden (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ................................................................. (02) 9230 3085 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Social Issues/Law ........................................... (02) 9230 2484 Jack Finegan (BA (Hons), MSc), Research Officer, Environment/Planning..................................... (02) 9230 2906 Daniel Montoya (BEnvSc (Hons), PhD), Research Officer, Environment/Planning ..................................... (02) 9230 2003 John Wilkinson (MA, PhD), Research Officer, Economics ...................................................... (02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. -

SYDNEY Ce Guide Au Format Numérique Www

+ plan détachable SYDNEY CITY GUIDE OFFERT ce guide au format numérique guide au format ce SYDNEY www.petitfute.com AFRIQUE - AMÉRIQUE LATINE - ASIE - AUSTRALIE - CANADA - BAHAMAS EUROPE - LES INDES - NOUVELLE ZÉLANDE - ORIENT - OCÉAN INDIEN PACIFIQUE - USA - TOUR DU MONDE - VOYAGE DE NOCES Voyage sur-mesure en Australie CONTACTEZ NOS SPÉCIALISTES 01 40 15 15 17 WWW.VACANCESAUSTRALIE.COM 31, avenue de l’Opéra (5e étage) 75001 PARIS Métro : 3 7 8 14 - Pyramides ou Opéra Cercle des Vacances : 31 avenue de l’Opéra ou 4 rue Gomboust 75001 Paris - S.A.S au capital de 2.200.000 € - N° d’immatricula- tion IM075100367 GIE ATOUT France : 79/81 Rue de Clichy, 75009 Paris - SIRET 500 157 532 000 10 - RCS Paris 500 157 532 - TVA FR75500157532 - Garantie financière APS : 15 av. Carnot 75017 Paris - Membre du SNAV. Photo © Annie Spratt ÉDITION Directeurs de collection et auteurs : Dominique AUZIAS et Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE Auteurs : Marie PLANCHAT, Philippe HENRY, Sophie ANSEL, Pascale GERSON, Welcome Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE, Dominique AUZIAS et alter Directeur Editorial : Stephan SZEREMETA to Sydney ! Rédaction Monde : Caroline MICHELOT, Morgane VESLIN, Pierre-Yves SOUCHET, Jimmy POSTOLLEC et Elvane SAHIN Remarquable par ses paysages et l’harmonie qui Rédaction France : Elisabeth COL, s’en dégage, cette ville jeune, née il y a 230 ans Silvia FOLIGNO, Tony DE SOUSA et Agnès VIZY du labeur des premiers colons, est également riche FABRICATION par sa diversité humaine. Dans cette métropole Responsable Studio : Sophie LECHERTIER assistée de Romain AUDREN qui s’étend de l’océan Indien aux pieds des Blue Maquette et Montage : Julie BORDES, Mountains, ce sont plus de 4,9 millions d’hommes Sandrine MECKING, Delphine PAGANO et Laurie PILLOIS et de femmes de toutes nationalités qui s’y croisent Iconographie : Anne DIOT et s’y pressent quotidiennement. -

1 Cathy Perkins. the Shelf Life of Zora Cross. Clayton

Cathy Perkins. The Shelf Life of Zora Cross. Clayton: Monash University Publishing, 2020. 285 pp. A$29.95. ISBN: 978-1-925835-53-3 Once a week for two years, I caught the bus from West End to Teneriffe in Brisbane for French classes, stepping off at Skyring Terrace near the new Gasworks Plaza. I was terrible at French and never did my homework, but I persisted out of a lifelong dream of writing in Paris. When I picked up Cathy Perkins’s The Shelf Life of Zora Cross, I realised that I was walking a street with a literary connection: Skyring was the surname of writer Zora Cross’s grandfather. Chance encounters bring us to poetry. In the basement of the Mitchell Library in NSW, a collection of letters led researcher Cathy Perkins to the author of the enormously popular Songs of Love and Life, published in 1917. Although this work sold four thousand copies via three reprints, by the time of Cross’s death in 1964 the author was slipping into obscurity. Two efforts had been made to draw attention to her importance in Australia’s literary history: Dorothy Green’s Australian Dictionary of Biography entry (1981) and an attempted biography by Michael Sharkey which was abandoned in favour of a biography of Cross’s partner, writer David McKee Wright. By the mid-1980s, Perkins writes, Cross had ‘fallen so far from literary consciousness that poets Judith Wright and Rosemary Dobson felt safe in recommending that the Australian Jockey Club name a horserace after her’ (86–87). By contrast Perkins, when she found a reference to Songs of Love and Life in the basement among the letters of George Robertson, publisher at Angus and Robertson, she was captivated. -

Graham Clifton Southwell

Graham Clifton Southwell A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Department of Art History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2018 Bronze Southern Doors of the Mitchell Library, Sydney A Hidden Artistic, Literary and Symbolic Treasure Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgements Chapter One: Introduction and Literature Review Chapter Two: The Invention of Printing in Europe and Printers’ Marks Chapter Three: Mitchell Library Building 1906 until 1987 Chapter Four: Construction of the Bronze Southern Entrance Doors Chapter Five: Conclusion Bibliography i! Abstract Title: Bronze Southern Doors of the Mitchell Library, Sydney. The building of the major part of the Mitchell Library (1939 - 1942) resulted in four pairs of bronze entrance doors, three on the northern facade and one on the southern facade. The three pairs on the northern facade of the library are obvious to everyone entering the library from Shakespeare Place and are well documented. However very little has been written on the pair on the southern facade apart from brief mentions in two books of the State Library buildings, so few people know of their existence. Sadly the excellent bronze doors on the southern facade of the library cannot readily be opened and are largely hidden from view due to the 1987 construction of the Glass House skylight between the newly built main wing of the State Library of New South Wales and the Mitchell Library. These doors consist of six square panels featuring bas-reliefs of different early printers’ marks and two rectangular panels at the bottom with New South Wales wildflowers. -

Robertson's Land Act - Success Or Failure?

University of Wollongong Historical Journal Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 4 1975 Robertson's Land Act - success or failure? Ruby Makula University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/hj Recommended Citation Makula, Ruby, Robertson's Land Act - success or failure?, University of Wollongong Historical Journal, 1(1), 1975, 42-64. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/hj/vol1/iss1/4 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Robertson's Land Act - success or failure? Abstract It is generally assumed that the Robertson Land Acts failed because they did not produce a closely settled rural population cf small farming freeholders. In this sense it is undoubtedly true that land reform in New South Wales "failed’', but this assumption presupposes that Robertson's Land Acts were formulated and passed primarily and fundamentally for the specific purpose which they failed to meet. It is suggest in this essay that behind the purported objective of 'unlocking the lands' for the benefit of the small farmer might be found aspects which alter the significance of the Land Acts, and give emphasis to the political, rather than social motivations of Sir John Robertson and his followers. This journal article is available in University of Wollongong Historical Journal: https://ro.uow.edu.au/hj/vol1/iss1/4 RCBEETSON' 3 LAITD ACTS - Success or Failure ? by Ruby Kakula It is generally assunad that the Robertson Land Acts failed because they did not produce a closely settled rural population cf scall fanr.ing freeholders. -

The Australian ‘Settler’ Colonial-Collective Problem

The Australian ‘Settler’ Colonial-Collective Problem Author Jones, David John Published 2017 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2241 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/365954 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au The Australian ‘Settler’ Colonial-Collective Problem David John Jones Dip VA, BVA Hons, MAVA Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Visual Arts Queensland College of Art Art, Education and Law Griffith University June 2017 1 Abstract This studio-based project identifies and interrogates the Australian denial of violent national foundation as a ‘settler’ problem, which is framed by the contemporary clinical and social concept of a ‘vicious cycle of anxiety’. The body of work I have produced aims to disrupt the denial of invasion and the erasure of Aboriginal culture through accepted narratives of European settlement of Australia. By aligning collective denial with anxiety, it presents a pathway for remediation through situational exposure; in this case, through works of art. The critical perspective on the invasion and colonisation of Australia is presented in the discursive and non- discursive modes of communication of the coloniser not to arbitrate or appease but to amplify the content. The structure of the exegesis also draws from Aboriginal narrative methodology and integrates with, and is informed by, the studio production in printmaking using demanding traditional European graphic techniques such as etching and aquatint. 2 Statement of Originality: This work has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any university. -

SIR SAUL SAMUEL Papers, 1837-1900 Reel M875

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT SIR SAUL SAMUEL Papers, 1837-1900 Reel M875 Sir John Samuel, Bart. Birchwood Beech Close Cobham, Surrey National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1973 CONTENTS Page 3 Biographical note 4 Correspondence of Charles Cowper and Saul Samuel, 1865-70 4 Letters of Lord Belmore to Saul Samuel, 1868-85 4 General correspondence, 1837-73 5 General correspondence, 1873-1900 12 Letters of Sir Henry Parkes to Saul Samuel, 1872-90 12 Undated letters 13 Invitations 13 Samuel Family papers, 1889-98 2 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Sir Saul Samuel (1820-1900), 1st Baronet, was born in London. His father died before he was born and in 1832 he accompanied his mother to New South Wales, where his uncle and his brother were already living. He was educated at Sydney College and in 1837 he joined the Sydney counting-house of his uncles. With his brother Lewis, he later formed the Sydney mercantile company of L. & S. Samuel and in time became a director of several companies based in Bathurst. Samuel was the first Jewish parliamentarian and the first Jewish minister of the Crown in New South Wales. He represented the counties of Roxburgh and Wellington in the Legislative Council in 1854- 56. In the Legislative Assembly he represented Orange in 1859-60, Wellington in 1862-69 and Orange in 1869-72. He returned to the Legislative Council in 1872. In 1865-66 and 1868-70 Samuel was Colonial Treasurer in the ministries led by Charles Cowper and John Robertson. He was postmaster-general in the ministries led by Henry Parkes in 1872-75, 1877 and 1878-80. -

A Critical Biography of Henry Lawson

'From Mudgee Hills to London Town': A Critical Biography of Henry Lawson On 23 April 1900, at his studio in New Zealand Chambers, Collins Street, Melbourne, John Longstaff began another commissioned portrait. Since his return from Europe in the mid-1890s, when he had found his native Victoria suffering a severe depression, such commissions had provided him with the mainstay to support his young family. While abroad he had studied in the same Parisian atelier as Toulouse Lautrec and a younger Australian, Charles Conder. He had acquired an interest in the new 'plein air' impressionism from another Australian, Charles Russell, and he had been hung regularly in the Salon and also in the British Academy. Yet the successful career and stimulating opportunities Longstaff could have assumed if he had remained in Europe eluded him on his return to his own country. At first he had moved out to Heidelberg, but the famous figures of the local 'plein air' school, like Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, had been drawn to Sydney during the depression. Longstaff now lived at respectable Brighton, and while he had painted some canvases that caught the texture and tonality of Australian life-most memorably his study of the bushfires in Gippsland in 1893-local dignitaries were his more usual subjects. This commission, though, was unusual. It had come from J. F. Archibald, editor of the not fully respectable Sydney weekly, the Bulletin, and it was to paint not another Lord Mayor or Chief Justice, First published as the introduction to Brian Kiernan, ed., The Essential Henry Lawson (Currey O'Neil, Kew, Vic., 1982). -

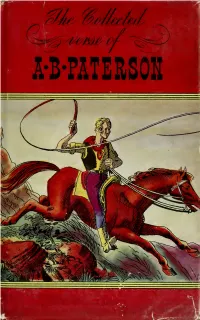

The Collected Verse of A.B. Paterson : Containing the Man from Snowy

The Collected Verse of A.B. ^^ Banjo^^ Paterson First published in 1921, The Collected Verse of A. B. Paterson has won and held a large and varied audience. Since the appearance of The Man from Snoiuy River in 1895, bushman and city dweller alike have made immediate response to the swinging rhythms of these inimitable tales in verse, tales that reflect the essential Australia. The bush ballad, brought to its perfection by Paterson, is the most characteristic feature of Australian literature. Even Gordon produced no better racing verse than "The Ama- teur Rider"' and "Old Pardon, the Son of Reprieve"; nor has the humour of "A Bush Christening" or "The Man from Ironbark" yet been out- shone. With their simplicity of form and flowing movement, their adventu- rous sparkle and careless vigour, Paterson's ballads stand for some- thing authentic and infinitely preci- ous in the Australian tradition. They stand for a cheerful and carefree attitude, a courageous sincerity that apart from is all too rare today. And, the humour and lifelikeness and ex- citement of his verse, Paterson sees kRNS and feels the beauty of the Australian landscape and interprets it so sponta- neously that no effort of art is ap- parent. In this he is the poet as well as the story-teller in verse. With their tales of bush life and adventure, their humour and irony "Banjo" Paterson's ballads are as fresh today as they ever were. (CoiUinued on back flap) "^il^ \v> C/H-tAM ) l/^c^ TUFTS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES nil 3 9090 014 556 118 THE COLLECTED VERSE of A. -

University of Queensland Library

/heuhu} CATALOGUE OF MANUSCRIPTS from THE HAYES COLLECTION In tlie UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND LIBRARY edited by Margaret Brenan, Marianne Ehrhardt and Carol Heiherington t • i w lA ‘i 1 11 ( i ii j / | ,'/? n t / i i / V ' i 1- m i V V 1V t V C/ U V St Lucia, University of Queensland Library 1976 CATALOGUE OF MANUSCRIPTS from THE HAYES COLLECTION CATALOGUE OF MANUSCRIPTS from THE HAYES COLLECTION in the UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND LIBRARY edited by Margaret Brenan, Marianne Ehrhardt and Carol Hetherington St Lucia, University of Queensland Library 1976 Copyright 1976 University of Queensland Library National Library of Australia card number and ISBN 0 9500969 8 9 CONTENTS Page Frontispiece: Father Leo Hayes ii Foreword vii Preface ix Catalogue of the Hayes Manuscript Collection 1 Subject index 211 Name index: Correspondents 222 Name index - Appendix 248 Colophon 250 V Foreword University Libraries are principally agencies which collect and administer collections of printed, and in some cases, audio-visual information. Most of their staff are engaged in direct service to the present university community or in acquiring and making the basic finding records for books, periodicals, tapes and other information sources. Compiling a catalogue of manuscripts is a different type of operation which university libraries can all too seldom afford. It is a painstaking, detailed, time-consuming operation for which a busy library and busy librarians find difficulty in finding time and protecting that time from the insistent demand of the customer standing impatiently at the service counter. Yet a collection of manuscripts languishes unusable and unknown if its contents have not been listed and published. -

IRSS 39 2014 MASTER (2 Sep)

INTERNATIONAL REVIEW OF SCOTTISH STUDIES ISSN 1923-5755 E-ISSN 1923-5763 EDITOR H. Parker, University of Guelph ASSISTANT EDITORS C. Holton, University of Guelph A. Glaze, University of Guelph REVIEW EDITORS M. Toledo Candelaria, University of Guelph A. Webb, University of Waterloo EDITORIAL BOARD M. Brown, University of Aberdeen G. Carruthers, University of Glasgow L. Davis, Simon Fraser University E. L. Ewan, University of Guelph D. Fischlin, University of Guelph J. Fraser, University of Edinburgh K. J. James, University of Guelph L. L. Mahood, University of Guelph A. McCarthy, University of Otago M. Penman, University of Stirling R. B. Sher, New Jersey Institute of Technology The Editors assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion made by contributors. All contents are © copyrighted by the International Review of Scottish Studies and/or their author, 2014 Book printing by Stewart Publishing & Printing Markham, Ontario • 905-294-4389 [email protected] • www.stewartbooks.com SUBMISSION OF ARTICLES FOR PUBLICATION This is a peer-reviewed journal. All manuscripts, including endnotes, captions, pictures and supplementary information should be submitted electronically through the journal's website (where all back issues can be accessed): www.irss.uoguelph.ca Submission guidelines and stylistic conventions are also to be found there. Manuscripts should be a maximum of 8000 words in length although shorter papers will also be considered. Contributors are requested to provide their title, institutional affiliation and current appointment. Book Reviews and Review Essays should be submitted electronically at: www.irss.uoguelph.ca To contact the editor: The Editor, International Review of Scottish Studies Centre for Scottish Studies Dept. -

The Man from Snowy River and Other Verses

The Man From Snowy River and Other Verses Paterson, Andrew Barton (1864-1941) University of Sydney Library Sydney 1997 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ © Copyright for this electronic version of the text belongs to the University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: The Man From Snowy River and Other Verses Andrew Barton Paterson Angus and Robertson Sydney 1917 Includes a preface by Rolf Boldrewood Scanned text file available at Project Gutenberg, prepared by Alan R.Light. Encoding of the text file at was prepared against first edition of 1896, including page references and other features of that work. All quotation marks retained as data. All unambiguous end-of-line hyphens have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. Author First Published 1895 Australian Etexts 1910-1939 poetry verse Portrait photograph: A.B. Paterson Preface Rolf Boldrewood It is not so easy to write ballads descriptive of the bushland of Australia as on light consideration would appear. Reasonably good verse on the subject has been supplied in sufficient quantity. But the maker of folksongs for our newborn nation requires a somewhat rare combination of gifts and experiences. Dowered with the poet's heart, he must yet have passed his ‘wander-jaehre’ amid the stern solitude of the Austral waste — must have ridden the race in the back-block township, guided the reckless stock-horse adown the mountain spur, and followed the night- long moving, spectral-seeming herd ‘in the droving days’.